Are Wolves Better Parents Than Humans Exploring Animal Family Bonds

8 min read Exploring whether wolf parenting outshines human family bonds through nature’s remarkable animal behaviors. (0 Reviews)

Are Wolves Better Parents Than Humans? Exploring Animal Family Bonds

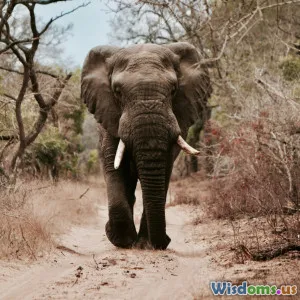

When considering the vast tapestry of family dynamics woven throughout the natural world, few comparisons captivate more than that of wolves and humans. Wolves, iconic symbols of wilderness and primal instinct, are often celebrated for their close-knit packs and devoted parenting styles. But could wolves truly be better parents than humans? This question probes beyond sentimentality to examine how nature defines parental success and deepens our understanding of family bonds in both species.

The Biology of Parenting: Wolves vs. Humans

Parenting, in biological terms, refers to the strategies and behaviors aimed at ensuring offspring survival and success into adulthood. Both wolves and humans invest considerable energy into their young, yet the methods and cultural implications vary widely.

Wolf Parenting: The Pack as a Family Unit

Wolves (Canis lupus) function within socially cohesive packs, generally consisting of an alpha pair and their offspring from several generations. The pack itself acts as a collective parenting unit—a rare trait among mammals—where all adults contribute to raising pups. This cooperative breeding system enhances pup survival rates dramatically.

For example, research shows that in Yellowstone National Park, wolf packs demonstrate remarkable teamwork: older siblings act as babysitters while the alpha pair hunts; adults regurgitate food for the pups and protect them fiercely from threats. This system ensures nearly every pup receives ample food, protection, and social learning opportunities.

Scientific studies published in journals such as Animal Behaviour confirm that such cooperative care can improve pup survival to over 70%, a significant rate in the wild. These tightly calibrated roles within the pack echo a biological imperative to survive in a harsh environment, yet they foster strong emotional bonds among all family members.

Human Parenting: Complexity and Variation

Humans (Homo sapiens), conversely, operate within not only biological but cultural contexts greatly influencing parenting styles. Human parenting is shaped by emotional nuance, education, social expectations, and economic factors, making it vastly more diverse and complicated than wolf pack parenting.

However, what human parents may lack in uniformity of care compared to wolves, they often compensate for in cognitive and emotional nurturing capacities. Human infants depend on long, sustained parental investment extending over many years—from feeding and protection as newborns to education and social guidance in adolescence.

While wolves have a relatively fixed life cycle where pups mature rapidly to independence by a year or two, human childhood spans over a decade, involving multilayered skill and knowledge acquisition. A study from Harvard University indicates that long parental investment in humans correlates with advanced cognitive development and complex social behaviors.

Emotional Bonds: Do Wolves Love Their Pups Like Humans?

Emotions, particularly love and attachment, profoundly influence parenting. Humans often anthropomorphize animals, projecting feelings based on human experience—but scientific observations demonstrate wolves' care goes beyond instinct.

Ethologist David Mech, a leading wolf expert, highlights wolves engage in behaviors suggesting attachment analogous to parent-child bonding in humans. Wolves communicate through tactile interactions such as nuzzling, licking, and close sleeping arrangements that reinforce social cohesion.

Moreover, wolves experience grief-like responses when losing pack members, indicating emotional depth within family bonds. These behaviors invite us to reconsider the often-assumed emotional exclusivity of humans in parental affection.

Social Structures and Survival: The Impact on Offspring

Wolves: Rigidity with Benefits

Wolf packs maintain structured hierarchies that determine caregiving roles and social status. This organization, while seemingly rigid, provides predictability and security for pups. Each member knows its task, minimizing conflicts and maximizing group survival.

Dominance is earned through social interaction rather than brute force, creating a stable social environment. This structure helps pups develop critical social cues essential for future hunting and pack coherence.

Humans: Flexibility with Challenges

Human families often contend with complex social challenges—economic pressures, cultural differences, and shifting social norms. Unlike wolves, human parenting is less about survival in the wild and more about integrating children into multifaceted societies.

Though flexibility allows for creativity and individual expression, it can also introduce stressors detrimental to parental consistency and offspring wellbeing, especially evident in high-conflict environments or socioeconomic hardships.

Yet, humans benefit from emotional support networks beyond immediate family—extended families, communities, and institutions—that augment parenting roles.

Lessons From Wolves to Humans: Can We Learn From Nature?

Considering the exemplary cooperative parenting found in wolves, what can human parents draw from their wild counterparts?

- Community Support Is Crucial: Wolves' success heavily relies on the entire pack’s participation. Human communities can foster stronger parenting by enhancing social support, sharing childcare duties, and minimizing isolation.

- Consistency and Role Clarity: Clear parental roles benefit wolf pups. For humans, clarity in parental involvement and responsibilities can improve child outcomes.

- Emotional Expression Strengthens Bonds: Wolves openly engage in affectionate behavior. Cultivating open emotional expression within families nurtures deeper connections.

Environmental psychologist Dr. Judith B. Scherer notes, "Nature demonstrates that raising children is not a solo journey but a shared endeavor with lasting impact on the social fabric."

Conclusion: Comparing Parenting—Different Metrics, Different Worlds

Are wolves better parents than humans? The answer lies not in who is superior but in understanding the distinct evolutionary paths shaping parental roles. Wolves excel in cooperative, efficient parenting focused on survival within a defined ecological niche. Humans exhibit unparalleled complexity, balancing biological imperatives with cultural, emotional, and intellectual development.

Both species showcase powerful family bonds essential for raising the next generation. By examining wolf parenting, humans gain a fresh perspective on community, cooperation, and emotional connection that can enrich our families.

In the grand narrative of life, wolves remind us that nurturing goes beyond biology—it’s a shared commitment implanted deep within the social heart of the animal kingdom.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts