Comparing Native Versus Non Native Plants in Public Gardens

16 min read Explore key differences and benefits of native versus non-native plants in public gardens. (0 Reviews)

Comparing Native Versus Non-Native Plants in Public Gardens

In cities and towns around the world, public gardens offer visitors a chance to experience nature’s beauty, breathe cleaner air, and deepen their appreciation for the environment. Behind every well-kept border and winding path, garden designers make crucial choices that influence not only aesthetics, but also ecology and sustainability. At the heart of these decisions is the question: should public gardens prioritize native plants, non-native species, or create a mix of both? The answer shapes everything from local biodiversity to garden maintenance demands and community learning opportunities.

The Case for Native Plants

Native plants—those that evolved naturally in a particular region—hold a special place in ecological landscaping. Because they're adapted to local soils, rainfall patterns, and climate fluctuations, natives generally thrive with less intervention. Consider the Midwest prairies of the United States: coneflowers, black-eyed Susans, and little bluestem grass once covered millions of acres, supporting an equally diverse array of bees, birds, and butterflies. Today, planting these and other Midwest natives in public gardens helps restore a slice of regional heritage while reducing ongoing maintenance needs.

Ecological Benefits

The ecological case for native species is compelling:

-

Biodiversity Support: Native plants serve as critical food and habitat sources for local wildlife. Iconic examples include the exclusive relationship between monarch butterflies and milkweed—monarch caterpillars only eat milkweed, and their populations decline sharply where these plants are absent. By prioritizing native species, public gardens can become oases for struggling pollinators and beneficial insects.

-

Soil Health and Water Conservation: Native root systems tend to grow deeper and wider than those of many non-natives, as they evolved to survive drought, fire, and seasonal extremes. Deep roots improve soil structure, prevent erosion, and promote groundwater recharge. For instance, California’s native fescues endure summer drought, requiring minimal supplemental irrigation compared to imported lawn grasses.

-

Resilience Against Pests: Plants that evolved locally develop natural defenses against native pests and pathogens. A stand of native oaks resists local beetles and fungi far better than a stand of exotic elms. This cuts back on pesticide use and keeps maintenance both eco-friendly and cost-effective.

Community Examples

- In Toronto’s High Park, nearly 50 percent of the flora is native to Ontario, drawing both wildlife and naturalists, and serving as a living classroom for botany—and conservation.

- The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Texas showcases over 900 species of native plants, providing educational programs focused exclusively on plant stewardship through natives.

The Appeal and Value of Non-Native Plants

Despite the clear benefits of native species, non-native (or exotic) plants have long been staples of public garden design. These are species intentionally moved to a new region by people, sometimes centuries ago. Tulips, roses, and crepe myrtles in North America are cherished horticultural imports—most loved for their blooms, form, or fragrance. Their presence in public gardens offers several distinct advantages that native-only landscapes might miss.

Aesthetic Variety and Seasonal Interest

Non-natives radically expand the designer’s palette. Springtime in Ottawa’s Commissioner’s Park, for example, bursts with millions of imported tulips, attracting tourists each May in a tradition dating back to World War II. Mediterranean lavender, Japanese cherry trees, and tropical cannas similarly headline public gardens around the globe, introducing colors, shapes, and fragrances unknown among local flora.

Urban Success Stories

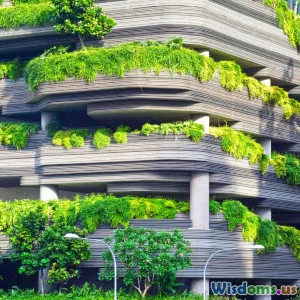

Certain non-native species perform exceptionally well in urban settings, where paved surfaces, reflected heat, and compacted soils create microclimates few natives can endure. London plane trees (a cross between American sycamore and Oriental plane) are renowned for their pollution resilience, forming shady corridors from Paris to Buenos Aires. In city centers where native canopy trees struggle, such adaptive, non-native selections fill critical ecological roles: reducing urban heat, filtering dust, and providing shelter.

Expanding Ecological Niches

Many public gardens operate as living catalogs for plants from around the world. At the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix, visitors can witness rare cacti from South America and Africa—educating the public about global plant conservation efforts and climate resilience, broadening appreciation for earth’s shared inheritance.

Invasiveness and Ecological Risks

The biggest concern attached to non-native plants is their potential to turn invasive and disrupt local ecosystems. Not all introduced species become destructive, but those that do can profoundly alter landscapes and native biodiversity.

Understanding Invasiveness

A non-native plant becomes invasive when it escapes cultivation, reproduces rapidly, and outcompetes local flora. Kudzu, imported from Asia for erosion control, exemplifies this problem in the American South. Climbing trees and shading out native understory, it has overwhelmed millions of acres, reducing wildlife habitat and costing millions in control efforts.

Other notorious examples include:

- Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria): Once prized in ornamental ponds, it now clogs North American wetlands, choking out cattails and vital amphibian breeding grounds.

- Japanese knotweed: Famous for its ability to crack pavement and devastate riverbanks across Europe, far outperforming many native riparian plants.

Garden selection committees must therefore balance the visual and educational benefits of non-natives with rigorous assessments of escape potential, limiting the use of species with a history of invasiveness.

Preventing Future Problems

Robust vetting is essential. Today’s best practices include:

- Consulting invasive species watch lists (such as those maintained by regional botanical societies or state agencies).

- Planting sterile cultivars when possible (which cannot produce viable seeds).

- Regular monitoring and immediate removal of weedy escapees from managed garden boundaries.

Maintenance, Resources, and Sustainability

Public gardens must be beautiful and welcoming, but also economically manageable. Plant choice strongly influences staff labor and input costs over decades.

Resource Requirements Compared

-

Irrigation: Native plants almost always need less watering after establishment, often no more than local rainfall demands. Eastern red cedar, for example, rides out droughts that would shrivel imported Japanese maples.

-

Fertilizers & Chemicals: Native species are tuned to local soils, requiring few amendments, whereas exotics may need fertilizers, soil acidifiers, or pest controls. Think of container specimens of acid-loving camellias from China, grown far from their native, humus-rich soils—these require regular tending beyond what most natives need.

-

Labor: Natives generally grow at a pace set by local seasons and conditions, minimizing rapid, out-of-control growth. Exotics bred for speed or showiness (like wisteria or golden bamboo) may demand constant pruning, thinning, or even periodic removal if they misbehave.

Urban Sustainability Initiatives

Increasingly, city horticulture departments push for sustainable landscapes, turning to native plant palettes to accomplish climate-resilient, low-maintenance parks. A 2017 survey found that over 80% of new municipal garden planning guidelines in North American cities now specifically recommend or require the use of native species, partly for resource savings and climate adaptation.

Educational and Cultural Considerations

Beyond their botanical value, public gardens function as informal classrooms, cultural spaces, and living museums. Plant choices here communicate powerful messages about local identity and global interconnection.

Interpreting the Landscape

-

Native plantings showcase regional history, land stewardship, and the unique ecological character of a place. Interpretive signage near prairie meadows in Madison, Wisconsin, for example, highlights their role in Indigenous agricultural systems and Midwest ecology.

-

Non-native displays offer global botanical literacy, allowing visitors to traverse continents without leaving home. The National Arboretum in Washington, D.C., features both American hollies and Asian bonsais, encouraging cross-cultural curiosity and respect.

Community Engagement

Programs involving local schools or community groups can use themed plantings:

- Replanting efforts in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park with locally rare natives—teaching urban youth about restoration and habitat.

- "International Garden" weeks in Montreal Botanical Garden, featuring rotating displays of plant traditions from the immigrant communities that shape the city’s identity.

In both cases, plant selection goes beyond petals and leaves: it constructs powerful narratives of place, belonging, and stewardship.

Navigating Design: Hybrid and Mixed Plantings

Though the debate often seems binary—natives or non-natives—the best-loved public gardens frequently weave the two together, with foresight and expertise.

Blended Borders: A Practical Approach

Many successful gardens utilize a matrix approach: structuring borders with ecological workhorses (such as tough grasses or shrubs) while spotlighting seasonal stars from both local and international origins. Chicago’s Lurie Garden is a masterclass, with its backbone of native grasses anchoring vignettes of allium, salvias, and tulips for four-season beauty. Licensed horticulturists routinely vet every non-native addition to ensure it poses no threat to local habitats.

Guidelines for Mixed Planting Success

- Prioritize diversity, but focus on non-natives proven to be non-invasive and non-disruptive.

- Use natives wherever foundational structure, pollinator habitat, or site restoration is most vital.

- Employ exotics for color, educational showcases, or microclimates natives can’t fill—with constant monitoring.

This approach leverages the resilience and ecosystem services of native plants while delighting visitors with global horticultural highlights, enriching both the landscape and the community it serves.

Tips for Garden Managers and Community Advocates

Given the complex variables of local context, visitor demographics, climate, and funding, staff and volunteers must weigh their priorities as they choose plants for public gardens.

Actionable Steps:

-

Assess Local Context and History: Chart which plant communities are naturally occurring or at risk in your region. Engage Indigenous or longtime residents, whose perspectives may illuminate lost or overlooked native plants with cultural significance.

-

Commit to Ongoing Education: Include plant labels noting native range and ecological value. Offer tours or events that explain why certain exotics were chosen and how their risks are being managed.

-

Balance Beauty and Function: Design with layered plantings for multi-season interest, integrating native “bones” (structure) throughout, with bold but safely-contained accent species.

-

Create Watch Lists: Even benign exotics can become problems under new climate regimes. Institute regular monitoring, and partner with local universities or citizen science groups for early detection of escapee plants.

-

Solicit Community Feedback: Use surveys or stakeholder meetings—visitors may have insights on plant preferences, new invasive issues, or opportunities for garden-based education.

-

Budget for the Long Term: Factor in the full lifecycle of each plant species, from maturity to removal, including potential pest and disease management.

Shaping the Future of Public Gardens

As climate change, urbanization, and biodiversity loss bring fresh challenges, the plant choices made within public gardens become ever more consequential. Striking the right balance between native and non-native plants ensures these sanctuaries remain not just attractive but ecologically robust, relevant, and meaningful.

Public gardens don’t need to ditch tulips or imported specimens—nor should they ignore the value of local flora. By blending evidence-based selection, cultural sensitivity, and future-minded stewardship, these living landscapes will continue to delight, educate, and sustain both communities and nature for generations to come.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Landscape Architecture

Popular Posts