Debunking Myths About Aging and Memory Loss

17 min read Explore common misconceptions about aging and memory loss, uncover scientific facts, and discover strategies for maintaining cognitive health as you grow older. (0 Reviews)

Debunking Myths About Aging and Memory Loss

Aging is both an inevitable process and a deeply personal journey. As we grow older, we're surrounded by cultural narratives, common misconceptions, and well-meaning—but often misinformed—advice about what happens to our minds. Many of us fear losing our mental sharpness, suspecting that "senior moments" are the first signs of something more serious. However, scientific research continues to give us hope, offering a far more nuanced and optimistic perspective. It's time to shed some light on the true relationship between aging and memory, busting persistent myths with facts, examples, and practical strategies for maintaining cognitive health into your later years.

Myth #1: Mental Decline Is Inevitable as You Age

Chances are you've heard the saying, "You can't teach an old dog new tricks." While memorable, this adage about mental inflexibility is outdated and misleading. Many people assume cognitive decline is an unavoidable consequence of getting older, but research tells a different story.

Separating Fact From Fiction

It is natural to experience some changes in cognitive abilities through the decades—such as slower recall or increased "tip-of-the-tongue" moments. But this does not mean everyone inevitably experiences significant memory loss or dementia. In fact, many older adults continue leading active, intellectually fulfilling lives with sharp minds well into their 80s and 90s.

The Science Speaks

A widely cited 2010 study published in the journal Neuron found that the brain remains malleable even in older age, capable of forming new connections—a concept known as neuroplasticity.[^1] While some memory processes (like recall speed) may slow down, other areas of intelligence, such as vocabulary, emotional regulation, and pattern recognition, often improve with age.

The Power of Lifelong Learning

Take Dr. Ruth Westheimer, the famous sex therapist, educator, and author, who in her 80s and 90s continued to write books and host seminars. Her example demonstrates that commitment to mental stimulation—not age—is a critical factor in cognitive vitality. The brain likes novelty and challenge. Whether it's learning a new language, playing an instrument, or tackling crossword puzzles, mental exercise helps keep cognitive skills sharp.

Myth #2: All Forgetfulness Signals Dementia

It's common to forget names or misplace your keys occasionally, but such slip-ups can cause alarm, especially in societies fixated on Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. The belief that benign forgetfulness is a certain sign of declining brain health is not only pervasive—it is also inaccurate and potentially harmful.

Normal Memory Lapses vs. Dementia

Everyday forgetfulness is part of being human, regardless of age. Younger adults forget things too, though these lapses can become more noticeable or frustrating as we get older. Dementia involves a progressive decline that impairs the ability to function independently—such as getting lost in familiar places, struggling to follow conversations, or drastic shifts in mood and personality.

Examples in Everyday Life

Suppose you struggle to remember where you left your glasses. That's common and not a red flag. But if you don't remember how to use the glasses or what they're for, that's a sign of a deeper issue requiring medical attention.

Stress, Sleep, and Multitasking

Simple forgetfulness can also be traced to poor sleep, high stress, nutritional deficiencies, and attempting to multitask. In fact, a Harvard Health study found that chronic stress can elevate cortisol levels, impairing the hippocampus—the brain region crucial for forming new memories.[^2] Addressing lifestyle factors often restores normal memory performance.

Myth #3: Older Adults Can't Learn New Skills

The image of elderly people struggling to keep up with new technologies is pervasive. Yet the stereotype that old age makes learning new skills impossible is erroneous and misleading.

Adult Learners and Neuroplasticity

Scientific studies show the capacity for learning does not vanish—though it might take more practice. For example, a Berlin study[^3] on older pianists who began lessons in their 70s found significant improvements in both cognitive functioning and dexterity after only a few months.

Real-World Inspiration

Consider Laura Ingalls Wilder, best known for her "Little House" books, who published her first novel at age 65 and wrote until her 80s. Or look at the many retirees who take up hobbies like photography, coding, or learning to use video chat to communicate with grandchildren. Adaptability, patience, and curiosity, not age, drive success.

Tech, Language, and Creativity

For those intimidated by today's tech landscape, community colleges, libraries, and online platforms like Coursera and Duolingo offer user-friendly classes designed for adult learners. Seniors who participate in lifelong learning activities often report higher overall life satisfaction and greater cognitive agility. A study in Gerontology,[^4] for example, linked participation in adult education to better memory function and psychological well-being.

Myth #4: Brain Games Are the Only Way to Boost Memory

The brain-training industry has exploded in recent years, promising sharper focus and better memory if you play certain games on your smartphone or computer. While these games can be fun and possibly helpful, they are not the exclusive or even the best way to improve brain function.

Beyond the Puzzle: Holistic Ways to Support Memory

Scientific reviews show that while specific brain games may improve abilities directly related to those games (such as Sudoku improving Sudoku-solving), evidence of these gains transferring to everyday life is limited.[^5]

Physical Activity: A Recurring Ally

A landmark 2018 trial published in Neurology found that moderate aerobic exercise improved memory scores in older adults after just six months.[^6] Exercise—like walking, dancing, swimming, or yoga—boosts blood flow, triggers brain growth hormones, and benefits overall brain health.

Social Interaction

Another undervalued mental workout? Social activity. Regularly connecting with friends, pursuing group hobbies, or joining clubs challenges the brain and fends off cognitive decline. According to a 2021 Neurology study, older adults with active social lives had memory performance equivalent to peers five years younger.[^7]

Nutrition and Sleep

Brain-friendly meals centered on fish, leafy greens, berries, and healthy fats along with sufficient sleep (7–8 hours for most adults) support memory retention. The combination of these daily habits—rather than any single "magic bullet"—offers the strongest evidence of benefits.

Myth #5: Genetics Determine Your Risk—You Can't Influence Memory Decline

Many resign themselves to the idea that memory problems are preset by family history. If your parents or relatives had dementia, you might feel destined for the same fate. Luckily, modern science shows that's only a small part of the puzzle.

Genes Are Not Destiny

While certain genes (for example, APOE-e4) increase dementia risk, having these doesn't guarantee cognitive decline. According to the Alzheimer's Association, genetics account for less than 15% of all Alzheimer's disease cases. The majority are attributed to a complex interplay between genetics and environmental factors.[^8]

The Power of Prevention

The groundbreaking 2020 Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER) showed a multidomain lifestyle intervention—combining exercise, nutrition, cognitive training, and vascular risk management—significantly slowed cognitive decline, regardless of genetic risk.[^9]

Healthy Habits That Make a Difference

- Keeping blood pressure and cholesterol under control

- Not smoking

- Regular cardiovascular exercise

- Mental and social stimulation

- Adequate sleep and stress management These are all actions within your control that can significantly reduce risk or delay onset—even in people with a family history.

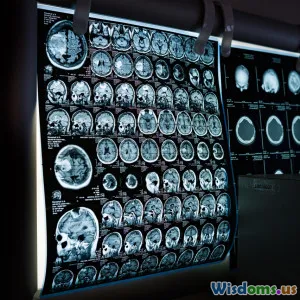

Myth #6: Memory Declines Uniformly Across the Board

Not all types of memory age at the same pace—or in the same manner. The myth that memory loss is an all-or-nothing affair ignores the complexity and resilience of the human mind.

Knowing Your Memory Types

- Episodic memory: Recalling specific events (like a recent trip), which may decline somewhat with age.

- Semantic memory: Facts and general knowledge, which often remain stable or even improve.

- Procedural memory: Skills and tasks (like riding a bike), usually well preserved.

- Working memory: Holding information temporarily (such as phone numbers) can be more vulnerable, but practice and memory strategies help.

Practical Example

Most older adults can vividly recount stories from their youth, demonstrate expert skills, or provide wise advice years after retirement. Many struggle less with forgetting critical life lessons or meanings than recalling what they ate for breakfast last week.

Tips to Harness Strengths

Maintain learning routines, write lists, use reminders, and stay organized. Emphasize storytelling, teaching others, or mentoring to reinforce semantic and procedural memory—contributing knowledge to family and community.

How To Protect and Sharpen Your Memory at Any Age

Living with a sense of control and agency can greatly minimize anxiety about cognitive decline. Here are evidence-based strategies that can make a measurable difference, regardless of when you start:

1. Cultivate Curiosity

Pursue interests and learn new things. Whether it’s an online course, a hobby, or learning to play an instrument, continuous mental stimulation strengthens the brain’s neuronal connections.

2. Move Your Body

Physical activity—especially cardiovascular exercise—fosters better blood flow and helps grow neurons. Even regular brisk walking for 20–30 minutes a day can improve cognitive performance.

3. Prioritize Quality Sleep

Adults frequently underestimate the cognitive drain of insomnia or poor sleep. Develop good sleep hygiene: set regular bedtimes, avoid screens late at night, and limit caffeine in the afternoon.

4. Nurture Social Connections

Relationships combat isolation and provide emotional stimulation, both of which are linked to lower rates of dementia and longer life spans. Schedule regular meetups, phone calls, or video chats.

5. Eat for Brain Health

Diets like the Mediterranean or DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) offer protection due to their emphasis on antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, and low intake of processed foods.

6. Manage Stress

Chronic stress erodes memory, impairs focus, and accelerates age-related health conditions. Mindfulness practices, such as yoga, meditation, slow breathing, or creative arts, offer science-backed benefits.

7. Address Health Conditions Promptly

Conditions like diabetes, hypertension, and even hearing loss have been associated with higher dementia risk. Schedule regular health screenings and treat underlying problems early.

Rather than accepting myths that reduce aging to unavoidable cognitive decline, embrace what the science says: memory, creativity, and learning are lifelong gifts that can be nurtured at any stage. Your brain is more adaptive and resilient than you might think. With a proactive mindset—and a few lifestyle tweaks—there's every reason to approach the decades ahead with optimism, enthusiasm, and curiosity.

References:

[^1]: Park, D.C. & Reuter-Lorenz, P. (2010). The Adaptive Brain: Aging and Neurocognitive Scaffolding. Neuron, 65(2), 183-206.

[^2]: Lupien, S.J. et al. (1998). Stress-induced declarative memory impairment in healthy elderly subjects: relationship to cortisol reactivity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 83(10), 3566-3571.

[^3]: Hanna-Pladdy, B., Mackay, A. (2011). The relation between instrumental musical activity and cognitive aging. Neuropsychology, 25(3), 378-386.

[^4]: Wänström, G. et al. (2016). Lifelong learning and healthy cognitive aging. Gerontology, 62(4), 354-361.

[^5]: Simons, D.J. et al. (2016). Do brain-training programs work? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17(3), 103-186.

[^6]: Stanley, J. et al. (2019). Exercise and the aging brain: considerations for maintaining cognitive health. Neurology, 93(9), 417-426.

[^7]: Crooks, V.C. et al. (2021). Social Activity and Cognitive Function in Older People. Neurology, 96(24), e2976-e2983.

[^8]: Alzheimer's Association. 2024 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia, https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures.

[^9]: Ngandu, T. et al. (2015). A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomized controlled trial. The Lancet, 385(9984), 2255-2263.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts