Does Multitasking Actually Kill Productivity The Facts Uncovered

7 min read Explore how multitasking truly impacts productivity, supported by psychology and neuroscience insights. (0 Reviews)

Does Multitasking Actually Kill Productivity? The Facts Uncovered

Introduction

In our fast-paced world, multitasking is often hailed as a superpower—the ability to juggle emails, calls, and reports all at once seems like the ultimate productivity hack. But is it really? Does multitasking boost your efficiency, or is it silently killing your productivity? This question intrigues not only professionals scrambling to get more done but psychologists, neuroscientists, and personal development experts alike. In this article, we unravel the truth behind multitasking from scientific, psychological, and real-world angles to help you understand whether multitasking is truly an effective work strategy or a costly myth.

The Psychology Behind Multitasking

What Happens in the Brain During Multitasking?

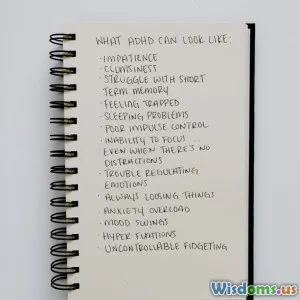

Multitasking is not what it seems. Neuroscience shows that the brain doesn’t perform two tasks simultaneously; instead, it switches rapidly between them—a process called "task switching." According to a seminal study by Rubinstein, Meyer, and Evans (2001) published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, this switching comes at a cost. Every time we move our attention from one task to another, it takes time to reorient—and this 'switch cost' reduces overall efficiency.

Further, research led by American cognitive psychologist David Meyer notes that even small rapid shifts of attention consume working memory resources, affecting cognitive control and accuracy.

Why We Think Multitasking Helps

Social conditioning and workplace culture promote multitasking as a mark of competence. In reality, this creates the illusion of productivity through constant motion and multiple open tabs on our computers.

However, as Stanford University psychologist Clifford Nass found, "heavy multitaskers" perform worse on tasks requiring sustained focus and working memory. This paradox highlights how our brains can get trained to handle distractions less effectively over time.

Real-World Evidence: Multitasking and Performance

Impact on Work Output and Quality

A 2009 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences observed that managers who engaged frequently in tasks requiring constant switching between emails, meetings, and phone calls had lower IQ scores at the end of the day—declines equivalent to losing a night’s sleep. Not only does multitasking reduce cognitive capacity, it also leads to more errors and slower task completion.

In another example, a software development company conducted an internal experiment where employees alternated between targeted, distraction-free blocks versus multitasking segments. The focused sessions yielded a 40% increase in deliverables and fewer bugs, illustrating the tangible trade-offs.

Multitasking and Stress

Juggling multiple tasks ramps up cortisol, the stress hormone. Chronic multitasking can lead to increased anxiety and burnout, as documented in a survey by the American Psychological Association showing that people who perceive multitasking demands often report higher stress levels.

Exceptions: When Multitasking Might Work

Not all multitasking is detrimental. Some routine or well-practiced tasks, especially those engaging different cognitive resources, can be done simultaneously without severe loss of quality.

Example: Walking and Talking

Walking downstairs while chatting rarely impacts either task significantly because the physical activity is largely automatic, needing less conscious control.

Example: Listening to Music While Doing Manual Tasks

Many people find that listening to music while doing repetitive chores improves mood and perceived productivity, though it’s not effective for tasks requiring deep concentration.

However, complex cognitive tasks demanding problem-solving or creativity should ideally be done in focused, uninterrupted intervals.

Implications for Personal Development and Workplace Habits

Fostering Single-Task Focus

Given the mounting evidence against multitasking, a key personal development strategy is cultivating the skill of sustained attention. Techniques like the Pomodoro Method or time blocking help condition the brain to focus on one task at a time.

Leveraging Environment and Tools

Minimizing notifications, organizing workspaces, and scheduling specific time slots for email check-ins can significantly lower the temptation or need to multitask.

Mindfulness and Cognitive Control

Practicing mindfulness meditation has been shown to increase attention span and reduce susceptibility to distractions. This enhances your ability to work deeply without the urge to switch contexts.

Conclusion

Multitasking, often glorified as a productivity booster, is largely a myth when it comes to complex and cognitively demanding work. Scientific research confirms that rapid task switching decreases efficiency, accuracy, and even cognitive capacity. While some low-effort multitasking may be harmless, truly maximizing your productivity requires embracing focused, deliberate work sessions and minimizing distractions. Personal development wise, training your brain to prioritize single tasks can not only improve output but enhance mental well-being.

The next time you catch yourself toggling between five tasks simultaneously, remember: less can be more. Focusing on one meaningful task is often the path to higher-quality work and sustained productivity.

References:

- Rubinstein, J.S., Meyer, D.E., & Evans, J.E. (2001). Executive control of cognitive processes in task switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27(4), 763-797.

- Ophir, E., Nass, C., & Wagner, A.D. (2009). Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(37), 15583-15587.

- American Psychological Association (2017). Stress in America survey.

- Meyer, D.E. & Kieras, D.E. (1997). A computational theory of executive cognitive processes and multiple-task performance. Psychological Review, 104(1), 3-65.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts