Ethics in Predictive Policing

10 min read Explore the ethical challenges and implications of predictive policing in modern law enforcement. (0 Reviews)

Ethics in Predictive Policing

Introduction: The Promise and Peril of Predictive Policing

Imagine a world where law enforcement could predict crimes before they happen. This may sound like science fiction, but predictive policing—using data and algorithms to anticipate criminal activity—is increasingly a reality across the globe. While hailed as a revolutionary technological tool designed to enhance efficiency and safety, it raises profound ethical questions that trap us in a complex intersection of technology, privacy, justice, and human rights.

As departments deploy predictive models, the urgent question becomes not just whether predictive policing works, but whether it should—and under what conditions. By peering beneath its digital veneer, this article dissects the ethical challenges at the heart of predictive policing, mapping its promises alongside lingering risks.

What is Predictive Policing?

Predictive policing uses mathematical models and historical crime data to forecast where and when crimes are likely to occur or who might be involved. It aims to allocate police resources more effectively, prevent crime through early intervention, and optimize public safety. Tools range from hotspot mapping—identifying high-crime areas—to individual risk assessments predicting recidivism or involvement in future offenses.

For instance, the Los Angeles Police Department's PredPol system analyzes crime patterns to forecast burglaries, vehicle thefts, and other property crimes, allowing patrols to target geographical hotspots. Similarly, Chicago's Strategic Subject List attempts to identify individuals at the highest risk of being involved in violent crime, either as victims or perpetrators.

Ethical Challenges

Bias and Discrimination

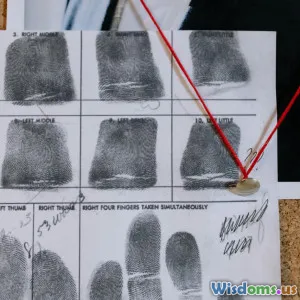

One of the most significant ethical concerns is the risk that predictive algorithms perpetuate or amplify existing biases in criminal justice data. Historical crime records reflect policing patterns influenced by historic discrimination, social inequalities, and systemic issues. When algorithms ingest these biased datasets, they tend to produce skewed predictions.

For example, studies reveal that African American and Latino neighborhoods are often disproportionately targeted due to the greater volume of past police encounters, not necessarily higher actual crime rates. This compounds the cycle of over-policing and distrust between communities and law enforcement.

In 2016, the investigative report by ProPublica exposed that COMPAS, a risk assessment algorithm widely used in U.S. courts, exhibited racial bias by overestimating Black defendants' likelihood of reoffending, potentially affecting sentencing unfairly.

Transparency and Accountability

Algorithms in predictive policing are often proprietary and operate as “black boxes,” where neither the public nor officers fully understand the decision-making process. This opacity raises concerns about accountability. If a faulty prediction leads to wrongful surveillance or arrest, who is held responsible—the creators, the police departments, or the system itself?

Moreover, citizens monitored or questioned based on algorithmic predictions might not even be aware that data-driven assessments influenced law enforcement actions against them. This lack of transparency conflicts with principles of procedural justice, which emphasize fairness and openness.

Privacy and Consent

Predictive systems often draw on vast amounts of data—including surveillance footage, social media activity, prior arrests, and neighborhood demographics—which raises severe privacy considerations. Citizens seldom consent to their personal data being harnessed for policing purposes, and the collection can intrude into private lives without probable cause.

The ethical quandary intensifies when these technologies blur lines between surveillance and social control. Some argue predictive policing creates “pre-crime” environments where people are treated as suspects based on statistical likelihood rather than concrete evidence, infringing on civil liberties.

Impact on Community Trust

Trust is a fragile yet essential foundation for effective law enforcement; however, reliance on predictive models can undermine community relations. Over-policing of minority neighborhoods fostered by flawed algorithms fuels resentment and fear.

Community members might perceive predictive policing as mechanized profiling rather than protective service. Ethical policing requires respect for human dignity and empowerment, which may be compromised if technology drives enforcement without meaningful human judgment and community input.

Real-World Implications and Examples

Case Study: Chicago Police Department

Chicago's Strategic Subject List algorithm, intended to identify individuals at risk for gun violence, generated controversy for its racial disparities and inaccuracies. Investigations showed that many flagged individuals had minimal involvement in violent crime or continued community engagement.

The program was criticized for labeling people as threats based on opaque criteria, intensifying surveillance rather than providing support or alternatives. It highlighted the dire need for transparency and community partnerships.

Lessons from the Los Angeles PredPol Experiment

While PredPol has been credited with lowering burglaries, independent assessments note it risks reinforcing existing biases. A 2019 Stanford study cautioned that quantity of prior crimes—rather than nuanced community context—drives predictions, potentially diverting resources away from underserved neighborhoods with unreported crimes.

Authorities there have since emphasized the integration of human oversight alongside algorithms, ensuring policing is not dictated solely by data.

Guiding Principles for Ethical Predictive Policing

Given these ethical dilemmas, several principles emerge as critical for responsible implementation:

1. Algorithmic Fairness and Bias Mitigation

Continuous auditing and refinement of datasets and algorithms are necessary to minimize bias. Tools should be rigorously tested across diverse demographic groups to avoid discriminatory outcomes.

2. Transparency and Public Engagement

Departments should openly disclose how predictive tools work, data sources, and decision-making processes, with access to audit results. Involving community stakeholders builds trust and legitimacy.

3. Data Privacy Protections

Clear boundaries must be established regarding data collection, storage, and usage, with individuals’ privacy safeguarded through anonymization where possible, and strict compliance with legal standards.

4. Human Oversight and Accountability

Predictions should inform but not replace police judgment. Oversight mechanisms must exist to review actions triggered by algorithms and ensure accountability for errors or abuses.

5. Social Support over Surveillance

Predictive policing efforts should link with social interventions addressing root causes of crime—such as poverty and education—not merely focus on enforcement.

Conclusion: Balancing Innovation with Ethics in Crime Fighting

The integration of predictive technologies into policing is inevitable, offering significant potential to enhance public safety and resource allocation. Yet, these innovations renew age-old questions about justice, fairness, and the role of technology in governance.

The ethical pitfalls—from bias and transparency deficits to privacy erosion and community alienation—are neither hypothetical nor distant. They reflect ongoing challenges that demand careful oversight, frank dialogue, and a willingness to prioritize human rights alongside innovation.

As we navigate the future of criminology and policing, ethics must cease being an afterthought. Instead, principled frameworks, inclusive governance, and constant vigilance will determine whether predictive policing becomes a trusted partner in justice or a catalyst for new inequities.

Ultimately, predictive policing offers tools—not answers. How societies wield these tools will shape the very fabric of security, democracy, and social trust for generations to come.

For further reading:

- “Machine Bias,” ProPublica, 2016

- Sandra G. Mayson, "Bias In, Bias Out," Yale Law Journal, 2018

- Lum and Isaac, "To predict and serve?", Significance, 2016

- Bradshaw, E. (2020). "The Ethics of Predictive Policing". International Journal of Tech and Ethics.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts