How the Maya Predicted Eclipses Without Modern Science

9 min read Explore how the ancient Maya accurately predicted eclipses using advanced astronomy without modern tools. (0 Reviews)

How the Maya Predicted Eclipses Without Modern Science

The ancient Maya civilization, flourishing in Mesoamerica from around 2000 BCE until the 16th century, has long fascinated historians and scientists. Among its many astounding achievements is their ability to predict solar and lunar eclipses with remarkable accuracy — all without telescopes, computers, or modern scientific instruments. How did a society without the tools we take for granted produce such precise astronomical forecasts? This article embarks on an exploration of the Maya's astounding astronomical knowledge and techniques that enabled these predictions, revealing the extraordinary intellect and dedication invested in their observations.

The Enigma of Maya Eclipse Predictions

Eclipses, both solar and lunar, are predictable celestial events governed by intricate celestial mechanics. Modern science understands and calculates these phenomena through gravitational physics and sophisticated algorithms. The Maya, however, achieved a similar predictive capacity through painstaking observations and ingenious calendrical schematics.

But why were eclipses so important to the Maya? The answer lies in their worldview and religion. The Maya considered eclipses as significant omens intertwined with the gods and cosmic order. Predicting them was not only a scientific challenge but a sacred duty tied to politics, religion, and societal cohesion.

Foundations: Maya Astronomy and Timekeeping

Obsession with Celestial Cycles

Maya civilization was deeply astronomical. They meticulously tracked celestial bodies: the Sun, Moon, Venus, Mars, and other planets. Much of this knowledge stemmed from centuries of consistent observations documented in codices, carvings, and inscriptions.

The Maya Calendars

Their prediction systems relied heavily on sophisticated calendrical frameworks:

- The Tzolk'in Calendar: A 260-day ritual calendar.

- The Haab' Calendar: A 365-day solar calendar.

- The Long Count: Tracking extensive historical timeframes.

The Maya combined these calendars to create a cyclical perception of time, which enabled them to link celestial events accurately to specific dates.

The Astronomical Tables: Dresden Codex

The most concrete evidence of the Maya’s prowess in predicting eclipses lies in the Dresden Codex, one of only four surviving pre-Columbian books. This richly illustrated manuscript includes detailed astronomical tables.

Lunar and Eclipse Tables

Within the Dresden Codex, a section known as the eclipse table spans approximately pages 51 to 58 and contains data on expected lunar and solar eclipses over a period of several decades.

Key characteristics include:

- Predictions are based on a series of consecutive intervals designed to track eclipse cycles.

- The tables show repeating intervals of roughly 177 and 148 days, which correspond closely to eclipse seasons when the Sun aligns with the Moon’s nodes — the intersection points of the Moon’s orbit with the Earth's orbital plane.

The Saros and Eclipse Cycles

This correlation hints at the Maya's understanding of eclipse cycles akin to the Saros cycle, known in modern astronomy to be about 18 years, 11 days, and 8 hours. The Maya achieved a similar forecasting method by correlating their observation intervals with known lunar nodal cycles, enabling predictions of when eclipses would reliably occur.

Methods Behind the Predictions

Lunar Nodes and Eclipse Seasons

The Moon’s orbit around the Earth is inclined about 5 degrees to the Earth's orbit around the Sun. Eclipses happen only when the Sun is near the Moon’s nodal points during a new or full moon — these times are the eclipse seasons.

Although the Maya lacked modern physics, they keenly observed these patterns. Through repetitive calculations and recordings, they identified the approximate durations between eclipse seasons (~173 to 180 days).

Counting and Recording Observations

Maya priests and astronomers maintained precise records of celestial events over decades. They employed numerical glyphs and cyclical calendars to keep track of intervals between eclipses and lunar phases.

Predictive Calculations

Using their calendars, astronomers generated future eclipse dates by:

- Marking known eclipse dates.

- Adding eclipse season intervals derived from prior observations (~177 days, for instance).

- Cross-referencing these intervals with the Tzolk'in and Haab' calendars to maintain accuracy over many years.

These calculations, although not formal mathematical equations as we understand them, constituted a robust predictive framework.

Supporting Archeological Evidence

Eclipses and Architecture

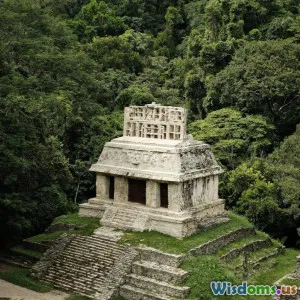

Structures such as observatories and temples were aligned with celestial bodies. The Caracol in Chichen Itza, a circular observatory, shows alignments with solar and lunar events, suggesting their direct use in monitoring celestial cycles.

The Role of Maya Astronomers

Known as Ah K'ihil (lineage of the sky watchers), these specialists occupied high status within Maya society. Their knowledge extended from divination and ritualistic importance to pragmatic calendrical and agricultural planning.

Modern Validation of Maya Predictions

Contemporary scholars, such as Anthony Aveni and David Kelley, have rigorously analyzed the eclipse tables in the Dresden Codex. By correlating known historical eclipse records with Maya data, researchers found an impressive alignment with actual eclipse events dating hundreds of years before European contact.

For example, the Maya accurately predicted lunar and solar eclipses within a margin of a few days, impressive given the manual recording system and absence of telescopes or modern calculations.

Their eclipse tables also revealed systematic errors, showing a critical and empirical nature rather than mere superstition or guessing.

Cultural and Scientific Significance

Astronomy and Religion

The ability to predict eclipses reinforced the Maya priesthood’s power. Eclipses were interpreted often as threatening events affecting rulers, crops, and cosmic balance. Predicting them allowed for ritual preparations, appeasement ceremonies, and political control.

Legacy and Inspiration

The Maya exemplify how human intellect, observation, and pattern recognition can yield sophisticated knowledge despite technological constraints. Their work encourages modern scholars to appreciate indigenous scientific methods historically marginalized.

The precision and dedication required for this astronomical mastery inspire contemporary astronomers and historians alike, fostering respect for ancient wisdom encoded in stone and codices.

Conclusion

The Maya civilization’s eclipse prediction highlights an extraordinary success story in ancient science. Without modern tools, technology, or physics, they created an empirical, reliable system based on long-term observations, detailed calendars, and clever cyclical calculations. Their achievements underscore a profound understanding of the heavens and verify that meticulous human observation can unlock cosmos mysteries even millennia ago.

Exploring how the Maya predicted eclipses enriches our appreciation for cultural diversity in scientific thought and opens windows into forgotten knowledge — a enduring testament to human curiosity and ingenuity.

References:

- Aveni, A. F. (2001). Skywatchers: A Revised and Updated Version of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico. University of Texas Press.

- Kelley, D. H. (1986). The Dresden Codex Eclipse Table: Resolution of a 400-year-old Mystery. Science, 232(4750), 541–544.

- UNESCO World Heritage - Chichen Itza: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/483/

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Mesoamerican Mythology

Popular Posts