OBEs and Nightmares Exploring Surprising Research Connections

16 min read Explore research linking out-of-body experiences (OBEs) and nightmares, revealing unexpected connections and psychological insights. (0 Reviews)

OBEs and Nightmares: Exploring Surprising Research Connections

The borderlands between wakefulness, dreaming, and the extraordinary experiences that sometimes punctuate sleep have captivated humanity for centuries. One of the most enigmatic intersections in this twilight zone involves Out-of-Body Experiences (OBEs) and nightmares. On the surface, they seem to belong to different realms of consciousness—yet cutting-edge scientific research is unraveling fascinating links between these two states, shining a new light on how our brains construct reality and perception.

The Science of Out-of-Body Experiences

Out-of-Body Experiences (OBEs) refer to episodes where individuals perceive themselves as floating or observing their own bodies from a vantage point outside their physical form. These phenomena aren’t merely the stuff of paranormal fiction. In clinical and neuropsychological literature, OBEs are recognized as real subjective events, occurring during waking states, near-death experiences, meditation, and most relevantly—during sleep and sleep paralysis.

What Happens in the Brain During OBEs?

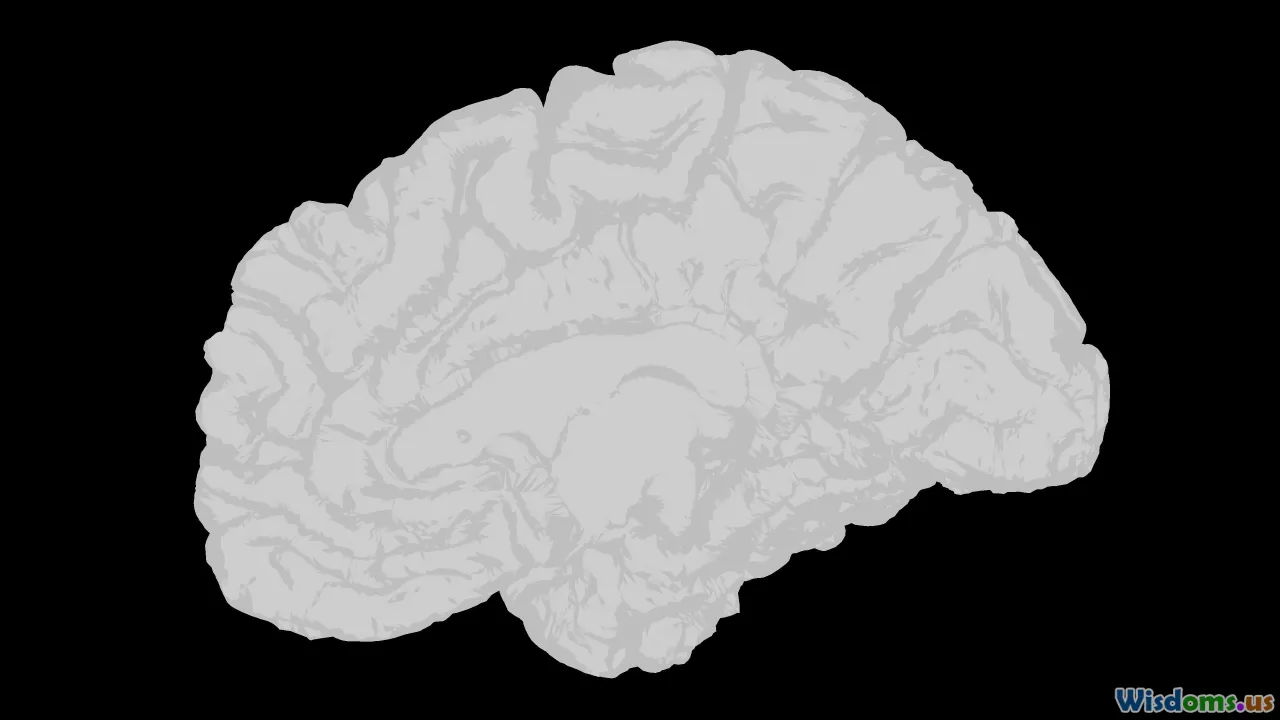

Recent neurological studies using fMRI and EEG scans suggest that OBEs frequently occur when the temporal-parietal junction (TPJ) in the brain experiences a disruption. The TPJ is responsible for integrating multisensory inputs and helps create our sense of corporeal self—the feeling that “this is my body.” Disruption, whether through electrical stimulation, epileptic activity, or certain dream states, can lead to a misalignment between the mind’s position and the body's perceived location.

For example, a 2002 study published in Nature described a patient who consistently experienced OBEs when neurosurgeons stimulated her right TPJ. Interestingly, people prone to OBEs also tend to score high in absorption and fantasy proneness, traits strongly linked with vivid imagery, creative thinking, and, notably, intense dream experiences.

Nightmares: More Than Bad Dreams

Most people are no strangers to nightmares—a subclass of dream marked by vivid fear, anxiety, or distress. They frequently result in awakenings, a racing heart, and sometimes a sense of helplessness. Nightmares aren’t just isolated to childhood; adult populations experience them, particularly during periods of stress, trauma, or a disrupted sleep schedule.

While people sometimes write off nightmares as simply "bad dreams," scientists now understand that they play an active role in emotional regulation. Nightmares frequently reflect deep-seated anxieties or unprocessed trauma and may signal underlying conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or mood disorders.

Significantly, nightmares often exhibit:

- High emotional intensity

- Enhanced sensory vividness

- Disordered sensations of time and space—features shared with OBEs.

Distorted Sense of Reality

The most unnerving nightmares can disrupt our sense of physical and emotional reality. Some nightmare sufferers report autoscopic experiences—moments when they see themselves from a typically unreachable perspective, often blending nightmare terror with features akin to OBEs.

Where OBEs and Nightmares Overlap

Perhaps the most surprising connection comes from sleep disorders and parasomnias, particularly sleep paralysis. Sleep paralysis occurs when an individual awakens from REM sleep but remains unable to move. During this boundary state, the mind is awake but the body remains paralyzed; hallucinations (including shadowy figures, voices, and sensations of being lifted) are common.

Shared Mechanisms: The Role of Sleep Paralysis

A groundbreaking study in the Journal of Sleep Research (2017) found that people who experience frequent OBEs are also more prone to sleep paralysis and nightmares. Surveys revealed that up to 40% of regular OBE experiencers reported episodes of nocturnal terror and immobilization. The same population often described unnerving sensations—such as floating outside the body, hearing indistinct voices, or a force pressing on their chest—all strikingly similar to both OBE narratives and nightmare archetypes.

A Case in Point

Consider the account of someone who regularly endures sleep paralysis. After the terrifying immobility, they suddenly feel their perspective shifting—as if hovering above the bed, observing their own frightened body. The scenario transitions from nightmare dread to an out-of-body narrative. Researchers propose that this shift may be due to fragmented integration of sensory information as the brain toggles between REM sleep and wakefulness.

Psychological Influences: Why Some People Are More Prone

Why are some people magnets for both OBEs and nightmares? Psychologists point to the role of personality and cognitive styles.

Fantasy Proneness and Absorption

Research shows that "fantasy-prone" individuals–those who frequently immerse themselves in vivid daydreams or imaginative activities–are much more likely to report both OBEs and recurring nightmares. High "absorption," a trait measured by the Tellegen Absorption Scale, often correlates with suggestibility, hypnotic responsiveness, and a thin boundary between imagined and waking experiences.

These traits may enhance the brain's ability to shift perceptual frameworks, loosening the anchors between the subjective self and the perceived body. Consequently, the borders between waking, dreaming, and dissociative experiences become permeable—opening the doors to OBEs during nightmare distress.

Trauma and Emotional Stress

Another robust predictor? Past trauma. Studies repeatedly show that individuals exposed to adverse events or ongoing psychological stress display higher rates of fragmented sleep, nightmares, and dissociation. In these cases, OBEs might function as an extreme "escape" mechanism—temporarily distancing the mind from the immediate sense of threat inherent in nightmares.

Neurobiology: How the Brain Creates Surreality

An essential aspect of the connection between OBEs and nightmares lies in how the brain encodes spatial awareness and emotional salience during REM sleep.

The Dreaming Brain's Spatial Maps

During REM, brain waves resemble waking patterns, but the connections between sensory input and higher-order reasoning are dampened. The TPJ, prefrontal cortex, and parietal lobes all play integral roles in self-location and agency. When their coordinated activity drifts—perhaps due to disrupted REM transitions, sleep deprivation, or abnormal neurotransmitter surges—people may simultaneously experience conviction that a nightmare is "real" and that the body is displaced, mirroring both derealization and OBE sensations.

Limbic Overdrive and Emotional Memory

The amygdala, center of the brain's emotional response system, is hyperactive during both nightmares and OBEs. It floods the dreaming state with fear, making emotional experiences hypervivid. Brain scans further suggest that decreased inhibition from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during these states reduces the capacity to reality-test, enabling vivid OBEs or nightmares to merge unchallenged with personal memory.

Real-World Application

Understanding these mechanisms helps clinicians differentiate between neurologically- and psychologically-triggered episodes, offering targeted interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy for nightmare disorder or EEG neurofeedback for dissociative experiences.

OBEs in Lucid Nightmares: A Special Genre

One of the most intriguing findings of recent decades is the fusion of OBEs and lucid nightmares—a special genre in which dreamers are consciously aware they’re in a dream and intentionally induce, or escape via, an out-of-body experience.

The Phenomenon of Lucid-Triggered OBEs

Lucid dreamers sometimes report using the sensation of floating out of their bodies to escape a threatening entity in a nightmare or to "reset" an anxiety-provoking scenario. Conversely, what begins as an OBE sometimes transforms into an uncontrollable nightmare, with dreamers losing agency and becoming passive observers.

A 2015 survey published in Consciousness and Cognition showed that about 12% of lucid dreamers had willfully triggered OBE-like transitions during unpleasant dreams, sometimes gaining an empowering sense of control, sometimes spawning deeper anxiety. The oscillation between fear, control, and dissociation is now a rich source of experimental research into consciousness boundaries.

Cultural Interpretations: From Witches to Neuroscience

The strange kinship between OBEs and nightmares is echoed in cross-cultural folklore, too. Across European, African, Asian, and Indigenous traditions, stories abound of malignant spirits, "hag attacks," or night journeys separating body and soul. Such myths likely arose as attempts to make sense of terrifying, paralyzing sleep episodes punctuated by shifts in body awareness—precisely the space where OBEs and nightmares overlap.

Folklore Meets Science

Modern neuroscience offers fresh interpretations of age-old experiences. What was once described as nocturnal spirits sitting on the chest, or witch-induced "soul flight," can now be correlated to REM atonia and the brain's attempts to reconcile immobility with a jarringly vivid dreamscape. These insights not only bridge science and myth but also foster better treatment for patients haunted by recurring sleep-related episodes.

Mitigating Nightmares and OBEs: Practical Advice

Awareness of the OBE-nightmare connection equips us to prevent and intervene in distressing experiences. Here are evidence-backed strategies for managing both phenomena:

Enhance Sleep Hygiene

Maintaining a stable sleep schedule, limiting screen exposure before bed, and creating a calm, dark, and cool sleep environment reduce the risk of fragmented sleep, sleep paralysis, and recurrent nightmares.

Mind-Body Techniques

Meditation, breathing exercises, and targeted muscle relaxation calm the nervous system before sleep. These approaches have been shown in clinical trials to lower anxiety, decrease adrenaline surges, and bolster sleep continuity. For individuals plagued by nightmares, practicing relaxation before bedtime can curb both frequency and intensity.

Journaling and Lucid Dream Training

Nightmare sufferers can benefit from keeping a dream journal. Recording dreams and related feelings recognizes recurring patterns and can prepare the mind to become "lucid"—self-aware—during distressing dreams, strengthening their ability to confront or alter the experience before slipping into a full OBE.

Lucid dream training, using methods such as reality-checks during the day or programmed awakenings during REM, helps reinforce introspective awareness within dreams. As awareness grows, the boundary between observer and dream material becomes more flexible, offering both mastery and novel opportunities for insight and growth.

Professional Help for Severe Cases

Severe, recurring OBEs and nightmares associated with trauma or mood disorders warrant expert attention. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I), imagery rehearsal therapy for nightmares, and trauma-informed psychotherapy have demonstrated efficacy for persistent or disabling disruptors of sleep.

The Future of Sleep Research: Uncharted Boundaries

Investigations into the shared terrain of OBEs and nightmares are transforming sleep science, consciousness research, mental health, and even literary and artistic traditions. Scientists now use portable EEGs, immersive virtual reality, and neurofeedback to simulate body-displacement scenarios, map live dream content, and guide clinical interventions. The overlap between OBE and nightmare research is especially rich for understanding how the brain negotiates boundaries, copes with fear, and expresses our deepest uncertainties.

As science continues to map the labyrinthine folds between sleep, dream, and selfhood, one thing grows ever clearer: The stories we live—whether glimpsed from above our bodies or woven in the nocturnal tapestries of nightmares—hold profound clues to the architecture of consciousness itself.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Out-of-Body Experiences

Popular Posts