The Mystery of Olmec Colossal Heads What Were Their True Purpose

8 min read Discover the true purpose and enigma behind the Olmec colossal heads, iconic sculptures of an ancient civilization. (0 Reviews)

The Mystery of Olmec Colossal Heads: What Were Their True Purpose?

The Olmec civilization, one of Mesoamerica's earliest and most influential cultures, left behind many enigmatic legacies, but none as iconic as their colossal heads. These giant stone sculptures, each uniquely detailed and intricately carved, beckon us to ask—what was their true purpose? Were they simply artistic representations, or did they serve a deeper symbolic or functional role within Olmec society? This article unpacks the mystery surrounding these megalithic monuments, exploring archaeological findings, cultural interpretations, and ongoing debates.

Introduction: A Monumental Puzzle

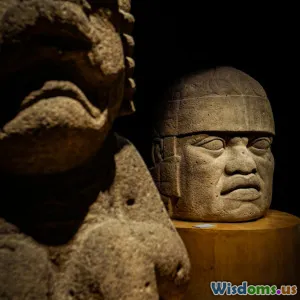

Standing between 1.5 and 3.4 meters tall and weighing several tons, Olmec colossal heads are among the most striking ancient artifacts discovered in the Americas. First unearthed in the 19th century but only fully studied in the 20th, these sculptures offer tantalizing glimpses into the enigmatic world of the Olmec.

What immediately captivates modern observers is their size, detailed craftsmanship, and the mysterious faces they depict, believed to represent powerful rulers or mythological figures. Yet despite decades of research, their true purpose remains an open question, inviting both scholarly inquiry and public fascination.

Origins and Discovery of the Olmec Colossal Heads

The Olmecs thrived approximately from 1400 BCE to 400 BCE in the tropical lowlands of what is now southern Mexico. Their colossal heads were primarily discovered at major ancient sites such as San Lorenzo, La Venta, Tres Zapotes, and Laguna de los Cerros.

Technical Marvels

Carved from basalt—a volcanic rock not native to many Olmec sites—these heads were quarried from distant locations, often several dozen kilometers away. Transporting these multi-ton sculptures and erecting them with Iron Age technology remains an extraordinary feat. Archaeologists estimate that moving a single head may have required organized labor forces and sophisticated logistical planning.

Physical Features

Each gigantic head bears distinct facial features: broad noses, thick lips, and sometimes helmet-like headdresses that may represent protection or ceremonial garb. This individualized style leads researchers to hypothesize that the heads portray specific Olmec rulers, ancestors, or elite figures.

Theories About Their Purpose

The debate over the colossal heads' purpose centers on several prominent theories, with considerable supporting evidence but no unanimous conclusion.

1. Portraits of Rulers or Elite Individuals

Many archaeologists propose that the heads are portrait sculptures celebrating important rulers or leaders, perhaps akin to royal portraiture in later civilizations. Supporting this is the individualized detail of the faces and the apparent depiction of helmets resembling those found in Mesoamerican ballgame gear, possibly implying warrior-kings or revered figures.

Anthropologist Michael Coe noted, "The fact that each head is different indicates individual identity rather than generic deity images."

2. Symbols of Political Power and Authority

The creation and display of such large stone monuments likely signaled the rulers’ socio-political power and their control over resources and labor. The effort required to sculpt, transport, and erect these colossal heads could have legitimized rulers’ dominance in the eyes of subjects and rivals alike.

3. Religious or Spiritual Significance

Another line of thought suggests these heads had spiritual or ritualistic roles. The helmets’ resemblance to shamanistic regalia and certain facial markings may signify divine authority or ancestral spirits guarding or blessing the community.

Some scholars connect the heads to Olmec cosmology or deities, positing an alignment with sacred sites or celestial events. However, this remains speculative, partly because Olmec writing and iconography are still only partially deciphered.

4. Commemoration of Ancestors or Mythical Heroes

It's possible the colossal heads served to immortalize legendary ancestors, heroes, or founding figures, thereby reinforcing group identity and cultural memory. The size and permanence of stone would enact a sort of tribute to those foundational individuals.

The Olmec Colossal Heads in Context

The colossal heads do not exist in isolation; they are part of a broader corpus of Olmec art and architecture.

Associated Artifacts and Sites

Many colossal heads are found in ceremonial centers with other sculptures, altars, and structures consistent with complex ritual activities. For example, at La Venta, heads are placed near what appear to be ritual plazas and pyramid platforms, indicating a ceremonial context.

Additionally, Olmec art features motifs like jaguars, serpents, and supernatural beings, which might provide insights into the symbolic meanings behind the heads if more direct connections are established.

Comparison with Other Megalithic Traditions

The Olmec heads can be compared with megaliths such as the Easter Island Moai or Egyptian pharaoh statues. In all, the scale underscores human endeavors to manifest power, religion, and memory through monumental art.

However, each culture reflects unique social, political, and spiritual values—highlighting the importance of studying the Olmec on their own terms rather than through external frameworks.

Challenges in Interpretation

Understanding the colossal heads’ true purpose is complicated by the scarcity of written records. Unlike cultures with extensive inscriptions, the Olmecs left few decipherable texts, making interpretations heavily reliant on archaeology, iconography, and comparative ethnography.

Furthermore, centuries of natural degradation and human disturbance have damaged some heads and their contexts, reducing available evidence.

Conclusion: Continuing the Quest for Clarity

The Olmec colossal heads remain among archaeology's most compelling enigmas. Were they monumental portraits, symbols of divine kingship, commemorations of ancestors, or combinations of these roles? The heads undoubtedly symbolize complexity, artistry, and power within an ancient civilization whose influence shaped Mesoamerican history.

Ongoing excavations, analytical technologies like 3D scanning and pigment analysis, and interdisciplinary scholarship promise to bring new perspectives. Yet, part of their allure lies in the mystery itself—a silent, stoic testament to human creativity and cultural depth that continues to command wonder and scholarly attention.

In exploring these behemoths carved in stone, we glimpse not just a past society but also enduring questions about identity, power, and the ways humans memorialize greatness across eras.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts