Understanding Crime Patterns in Society

8 min read Explore the dynamics of crime patterns in society, revealing the factors shaping criminal behavior and uncovering insights for effective prevention. (0 Reviews)

Understanding Crime Patterns in Society

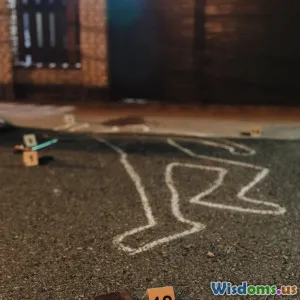

Crime is not random; it follows identifiable patterns that criminologists and law enforcement study to predict, prevent, and solve offenses. Analyzing these patterns reveals profound insights into the forces shaping not only criminal behavior but also society itself. In this article, we’ll dive into the complexities of crime patterns, exploring their causes, examples across different contexts, and implications for crime prevention.

Introduction: Why Crime Patterns Matter

Picture a city where violent incidents spike unexpectedly in certain neighborhoods, or where cybercrimes burgeon alongside evolving technology. Understanding these crime patterns isn’t just academic—it’s essential for policymakers, investigators, and communities.

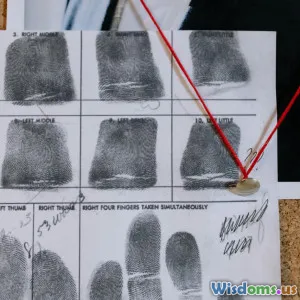

Crime patterns are the fingerprints of societal malaise, reflecting underlying issues of inequality, urban design, social cohesion, and more. Examining these patterns enables better allocation of resources and smarter policies. As famed criminologist Patricia L. Rosenberg notes, “Patterns don’t merely tell us what happened; they hint at why, and how to intervene.”

Body

1. Defining Crime Patterns

Crime patterns refer to the observable regularities in the occurrence, type, location, and timing of criminal activities. These patterns help form predictive models that law enforcement agencies use.

- Spatial patterns focus on where crime happens. For example, urban “hot spots” often experience higher crime rates due to factors like poverty or poor lighting.

- Temporal patterns look at when crimes take place—day vs. night or seasonal fluctuations.

- Victimology patterns explore which groups are targeted more frequently and why.

2. Key Theories Explaining Crime Patterns

Several criminological theories strive to explain why crime clusters and patterns develop:

-

Routine Activity Theory: Proposed by Lawrence Cohen and Marcus Felson in 1979, this theory posits that crime occurs when a motivated offender and a suitable target converge in the absence of capable guardianship. For instance, unlocked homes in an unsafe neighborhood during evening hours create a ripe opportunity.

-

Social Disorganization Theory: This holds that crime rates are higher in communities with weakened social institutions like family, school, and local government. The Chicago School’s studies of urban decay illustrate this clearly.

-

Strain Theory: Suggests that crime results when individuals experience pressure from societal inequalities or failures to achieve culturally valued goals. An example is economic disparity prompting theft or drug-related crime.

-

Environmental Criminology: Focuses on how physical spaces influence criminal behavior. Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) applies this to practical measures like secure lighting or open sightlines.

3. Real-World Crime Patterns and Examples

-

Urban Crime Hotspots: Cities worldwide see crime concentrated in specific areas. For example, in New York City, neighborhoods within the Bronx historically had elevated rates of violent crimes during the 1990s. Concentrated police efforts in “hot spots” have been shown to reduce crime effectively.

-

Temporal Crime Trends: Studies show burglars tend to prefer daylight hours when homes are empty. Cybercrimes spike around major shopping events such as Black Friday and holiday seasons due to increased online activity.

-

Demographic Patterns: Young males are statistically more often involved as offenders and victims of violent crime globally. Conversely, cybercrime perpetrators often span wider demographic categories.

4. Data and Technology in Understanding Crime Patterns

The rise of big data and AI has transformed crime pattern analysis.

-

Predictive Policing: Software like PredPol uses historical crime data, geographic info systems (GIS), and machine learning to forecast where crimes might occur. This technique was credited with significant crime reductions in places like Los Angeles.

-

Crime Mapping: Interactive tools empower communities to visualize local crime trends, improving awareness and collaborative prevention efforts.

However, ethical debates exist around surveillance and potential biases in algorithmic policing.

5. Implications for Crime Prevention and Policy

Identifying and understanding crime patterns empowers more strategic crime prevention:

-

Targeting Hot Spots: Concentrated policing and urban improvement can mitigate high-risk areas without over-policing entire communities.

-

Community Engagement: Strengthening social institutions and local networks addresses root causes described in Social Disorganization Theory.

-

Environmental Design: CPTED principles can be embedded in urban planning, reducing opportunities for crime.

-

Education and Economic Opportunities: Addressing societal strains through education and social services reduces motivations for crime.

Conclusion: Towards a Safer Society Through Insightful Analysis

Crime patterns serve as mirrors reflecting societal strengths and vulnerabilities alike. By decoding these patterns through rigorous analysis and collaborative effort, communities can not only predict criminal trends but disrupt them meaningfully.

In the words of criminologist Donald J. Newman: “Understanding the patterns of crime is not merely about prediction – it is about creating conditions where crime struggles to take root in our societies.” Armed with data, theory, and community insight, we move closer to this vision.

As society evolves, ongoing research and adaptive policies remain crucial. Awareness and informed action today pave the way for safer, more resilient communities tomorrow.

References and Further Reading:

- Felson, M. & Cohen, L. E. (1979). "Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach".

- Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). "Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy".

- Braga, A. A., Papachristos, A. V., & Hureau, D. M. (2014). "The Effects of Hot Spots Policing on Crime".

- Weisburd, D., Telep, C. W., Weiher, A. W., & Hinkle, J. C. (2010). "Is problem-oriented policing effective in reducing crime and disorder?".

Understanding crime patterns illuminates pathways to prevention and justice, highlighting the profound intersection between society’s structure and its safety.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts