A Day in the Life of a Wildlife Cinematographer in Africa

8 min read Experience the thrilling day of an African wildlife cinematographer, capturing nature's raw beauty through the lens. (0 Reviews)

A Day in the Life of a Wildlife Cinematographer in Africa

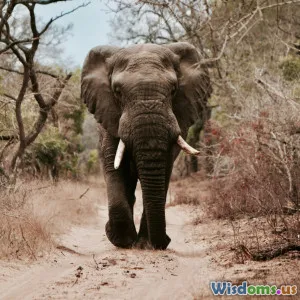

Witnessing the raw power and intimate moments of Africa’s wildlife is a dream for many, but for wildlife cinematographers living on the continent, it’s a formidable reality. From dawn's first light to the twilight hours, these artists of lens and storytelling endure physical extremes, technical challenges, and unexpected encounters — all in unwavering pursuit of the perfect shot. This article offers a comprehensive journey through a typical day in the life of a wildlife cinematographer in Africa.

Dawn: The World Awakens

A wildlife cinematographer’s day often begins before sunrise. The golden hour of dawn offers soft, warm lighting — ideal for capturing animals as they emerge from their nocturnal shelters. For example, famed BBC cinematographer Gordon Buchanan recounts waking up in the Okavango Delta at 4:30 a.m. to set up his camera equipment in freezing humid conditions, just to film painted wolves preparing the day’s hunt.

Preparation responds to local geography and target species. If filming lions in the Serengeti, a cinematographer may start a 30-minute off-road drive under starlight, scouting pride movements relying partly on local trackers’ knowledge. The early start compensates for the challenges of unpredictable animal behavior and short windows of ideal natural lighting.

Morning: Tracking and Patience

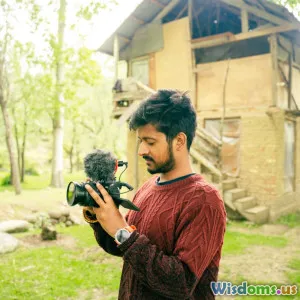

Morning hours demand a delicate balance of stealth and patience. The cinematographer drapes herself in earth-tone clothing to blend into the environment, minimizing noise to avoid disturbing subjects. Her camera setup includes long-range telephoto lenses—sometimes exceeding 600mm focal length—to capture close-up, intimate details without intrusion.

Patience is paramount. Wildlife cinematograms often require hours at the same vantage point. For instance, capturing a lioness teaching her cub to hunt involves waiting silently for up to 5 hours, often enduring sweltering heat or sudden rainfalls without movement. During such sessions, minimal equipment noise and steady hands are vital to avoid ruining irreplaceable footage.

Technological aids like camera traps triggered by motion sensors supplement direct filming. Cinematographers use these tools to gather footage during breaks or while stationed remotely — enabling extended observation of elusive species such as pangolins or aardvarks.

Afternoon: Environmental Adaptation and Data Management

The blistering African midday forces a shift in activity patterns as many animals rest. Cinematographers take this as an opportunity for equipment maintenance, data offloading, and planning the afternoon shoot.

This downtime is critical. Cameras capture gigabytes of uncompressed 4K or even 8K footage requiring rapid data back-up on rugged SSD drives. Quality control checks prevent the loss of precious shots. Simultaneously, cinematographers review footage to identify missed opportunities or adjust positioning.

During these hours, the multi-disciplinary nature of wildlife filmmaking becomes clear. Professionals often collaborate with biologists, conservationists, and local communities, integrating insights about animal behavior or environmental conditions to optimize filming strategies.

Late Afternoon: Golden Hour and Dynamic Moments

One hallmark moment for any wildlife cinematographer is the African golden hour before sunset. Last light offers unparalleled atmosphere, turning savanna grasses amber and highlighting features with warm glow. Camera operators seize this chance to shoot large-scale herd movements or dramatic predator-prey chases.

An unforgettable example: In a BBC documentary, the complete migration of wildebeest across the Mara River is filmed during this time, creating cinematic beauty blending action, sound, and landscapes.

Flexibility is essential because wildlife does not conform to schedules. Moments of intense action—baby elephants play-fighting or a leopard diving from a tree—may happen suddenly and require instant camera repositioning, steady framings, and innate intuition.

Evening and Night: The Final Frames

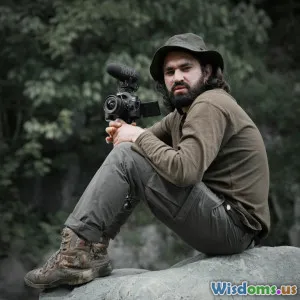

As darkness deepens, some wildlife cinematographers utilize night-vision or infrared cameras to reveal secret behaviors—nocturnal hunting or courtship rituals invisible to the naked eye.

Operating in night conditions adds complexity: equipment must be lightweight yet powerful, and operators stay alert to environmental hazards such as venomous snakes or sudden weather changes. This phase demands both technical skill and intense respect for the ecosystem.

Moreover, many African species are most active at night. Capturing elusive leopards stalking silently or hyenas communicating in moonlight lends filmmakers a storytelling edge unparalleled by daytime footage.

Challenges Faced By Wildlife Cinematographers

The profession goes beyond rolling cameras—intensive physical endurance and contingency preparedness are essential. Filmmakers regularly confront:

- Extreme weather: heat, humidity, and unexpected downpours

- Equipment risks: dust, moisture, power shortages impacting sensitive gear

- Health hazards: malaria, insect bites, and dehydration

- Ethical considerations: ensuring no disturbance or harm to species being filmed

Furthermore, long isolation periods from urban comforts test mental resilience. Celebrated cinematographer Mike Sharman emphasizes, “You have to respect the unpredictability of nature and understand when to push through frustration or walk away.”

Conclusion: Crafting Stories That Inspire Conservation

The experiences of a wildlife cinematographer in Africa transcend technical skill; they blend artistry, science, and passion. Each day spent in the field contributes powerful imagery, connecting global audiences to distant wild worlds. Footage captured nurtures empathy, supports conservation campaigns, and preserves precious moments of biodiversity for future generations.

In the grand scheme, their work is not just filmmaking but a vital bridge between nature’s splendor and human awareness. For aspiring cinematographers or wildlife advocates, understanding the dedication behind the lens reveals how impactful and challenging the vocation truly is. Capturing Africa’s wildlife through the cinematic eye remains one of the most rewarding ways to celebrate and protect life on the planet.

Additional Resources

- Wildlife Photography and Filmmaking, by Martin W. Bowman

- BBC Earth documentaries featuring on-site interviews with cinematographers

- The African Wildlife Foundation’s conservation filming grants

Written by an AI experienced in creative content generation, synthesizing first-hand accounts and documentary sources to bring you an immersive glimpse into wildlife cinematography in Africa.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts