Are revenue based options better than equity for bootstrapping

35 min read Compare revenue-based financing and equity for bootstrapped startups, covering costs, dilution, cash flow impact, eligibility, and fit by business model with practical examples. (0 Reviews)

Bootstrapping used to mean starving your company until customers funded it. Today, founders can choose from a spectrum of capital that sits between doing nothing and selling a big chunk of equity. The most common of these middle paths are revenue-based options: financing that gets repaid from revenue, often with a capped return. These instruments promise control without dilution, but they also tug on cash flow when you need it most.

If you’re wondering whether revenue-based options are better than equity for bootstrapping, the honest answer is that it depends on your margins, growth path, appetite for risk, and goals. What follows is a practical guide to help you decide: definitions, scenarios, numbers you can copy into a spreadsheet, negotiation tips, and pitfalls to avoid.

What we mean by revenue-based options

Revenue-based options refers to financing structures where you repay investors through a slice of revenue until a defined cap or fee is satisfied. They go by several names and vary in mechanics:

- Revenue-based financing (RBF): You receive capital now and repay a fixed multiple (for example, 1.3x–2.0x the advance) as a percentage of monthly revenue, commonly 2%–10%, until the cap is reached.

- Shared earnings agreements: Similar to RBF, but payments may be tied to founder income or profitability instead of strictly top-line revenue; often seen in calm-company ecosystems.

- Merchant cash advances (MCAs): A close cousin used in e-commerce and retail, repaid daily from sales with a fixed factor fee and typically shorter durations (3–12 months).

- Redeemable or buyback equity: You sell equity but with a contractual right or obligation to repurchase investor shares later, sometimes funded by a revenue share.

- Inventory and receivables financing: Not pure revenue share, but revenue-like in spirit: repay lenders as inventory sells or invoices are collected; frequently used in e-commerce and B2B.

What these structures share is alignment with cash generation rather than a binary exit event. Instead of asking whether your company will become a unicorn, investors ask whether your revenue is predictable enough for them to get repaid.

Equity basics and why founders choose it

Equity involves selling ownership in your company in exchange for capital. It comes as priced rounds, SAFEs, and convertible notes. Key characteristics:

- Dilution: You trade a percentage of your company for money. If the company becomes valuable, that dilution represents a big cost of capital.

- No contractual repayments: Cash remains inside the business until there’s an exit or dividends, which is helpful during long periods of investment.

- Investor rights: Board seats, pro rata, information rights, and protective provisions can shape strategy. Expectations for pace and scale are often higher.

- Time horizon: Venture equity aims for 7–10 year fund cycles and home-run outcomes. That can be mismatched with calm, profitable businesses.

The main reason to choose equity is to fund long runways and aggressive experimentation when there isn’t enough revenue predictability to service debt-like payments. Equity shines for big, risky bets with long R&D cycles, network effects, or regulated markets.

The core trade-off: dilution vs. cash flow drag

Revenue-based options preserve ownership but create a tax on growth: every month a slice of your revenue flows to an investor. Equity avoids that tax but sells compounding upside.

Think about this as two curves:

- Dilution cost increases with success. The more valuable you become, the more the sold equity costs you in absolute dollars. For example, 15% of a $100 million exit is far more expensive than repaying a $1 million revenue-based advance at a 1.7x cap.

- Cash flow drag hurts the most early. Revenue-based payments reduce working capital and may slow growth if your customer acquisition and hiring are sensitive to cash on hand.

The decision turns on your margin structure, the speed of your payback loops, and your confidence in large outcomes. If you have high gross margins and short payback on marketing spend, a revenue-based instrument can be fuel without selling tomorrow’s upside. If your business needs long, loss-making phases, revenue-based instruments can strain your runway at the worst times.

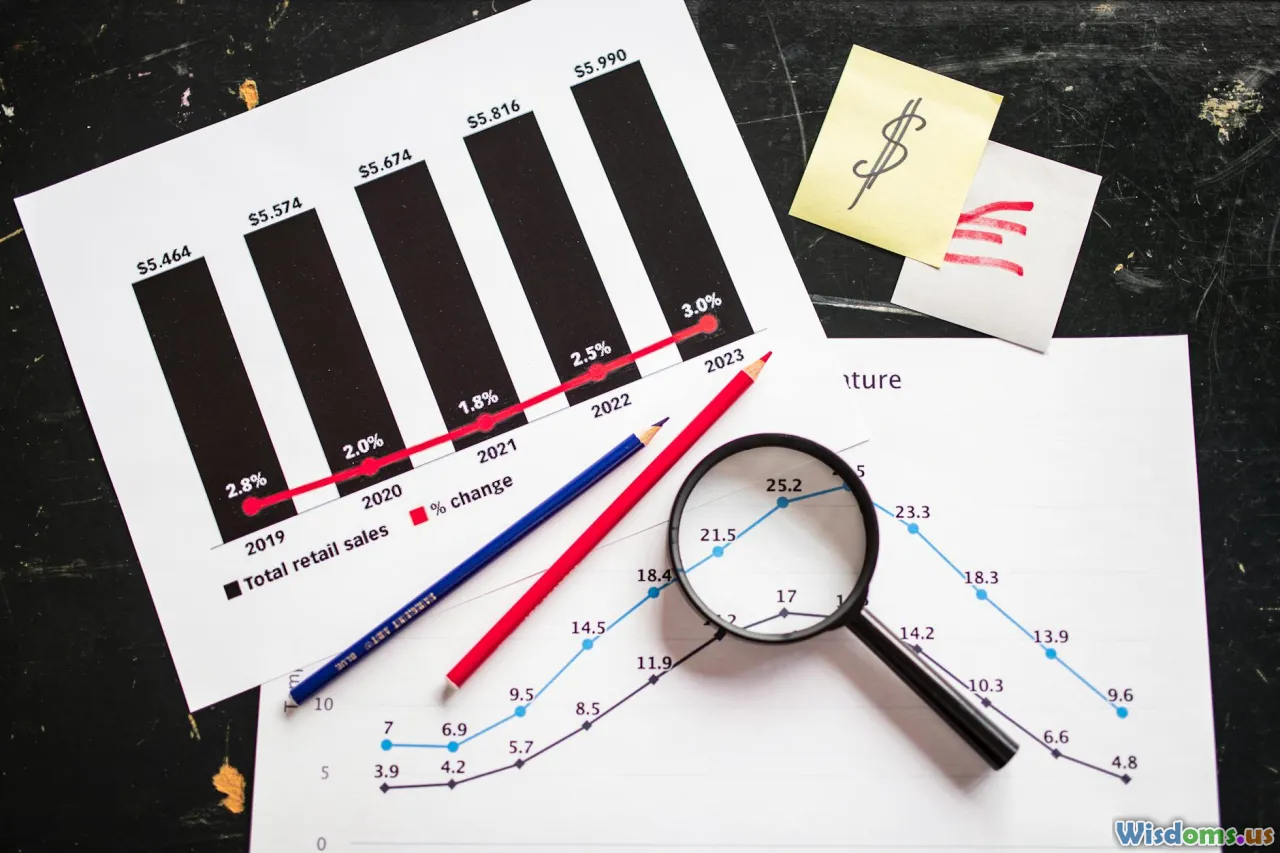

A numerical walkthrough: SaaS example at 50k MRR

Consider a B2B SaaS doing 50k MRR ($600k ARR), 80% gross margins, and 85% logo retention. CAC payback is 8 months on blended spend. The team runs at a 40k monthly operating expense excluding cost of revenue, and they want 500k to fund growth.

Scenario A: Revenue-based financing

- Advance: 500k

- Cap: 1.7x (total repayment 850k)

- Payment: 6% of monthly revenue until cap is reached

- Fees/closing: negligible for simplicity

Month 1 payments at 50k MRR: 3k (6% of 50k). As MRR grows, so do payments.

Suppose MRR grows 8% compounded monthly for 12 months, then 5% monthly for 12 months, then 3% monthly for the following 12 months. Roughly:

- End of year 1: ≈ 108k MRR

- End of year 2: ≈ 158k MRR

- End of year 3: ≈ 206k MRR

Payments over the period scale from 3k/month to around 12k/month by end of year 3. If we sum a rough estimate of payments at an average 8k per month over 36 months, that suggests 288k paid — clearly too low relative to the 850k cap. But because payments scale, a more precise model shows the cap being reached in about 40–48 months given this growth path. The implied IRR to the investor might fall between 18% and 28% depending on exact timing.

What matters to the founder is the cash drag. In year 2, with 130k average MRR, monthly payments at 6% are 7.8k. If your gross margin is 80%, gross profit is 104k; 7.8k is 7.5% of gross profit. If your operating spend is a flexible 60–80k, that payment is material but not fatal.

Scenario B: Equity

- Raise 500k at a 4.5m pre-money valuation via a priced round or SAFE with valuation cap

- Post-money 5.0m, sale is 10% of the company on a fully diluted basis

You now have no contractual payments. If you keep the same growth path and sell for 50m in five years, that 10% costs you 5m (ignoring preferences). The RBF would have cost you 850k.

But if you never sell, the math flips: the equity may never be realized, whereas the RBF is paid regardless and consumes cash along the way.

A blended lens: If the founder believes the most likely outcomes are a profitable business with occasional distributions or a smaller acquisition (say 5–15m), RBF may dominate. If the founder is aiming for a 100m+ outcome, equity often looks cheaper in hindsight despite dilution.

When revenue-based options shine

Revenue-based instruments are at their best when:

- You have recurring or highly predictable revenue. SaaS MRR/ARR, subscriptions, or steady e-commerce sales with repeat purchase patterns.

- Gross margins exceed 60%. High margins leave more room to service payments without starving growth.

- CAC payback is short. If new customers pay back in 6–9 months, you can keep acquiring even while making revenue-share payments.

- You value control and optionality. Avoiding board seats and protective provisions keeps you nimble.

- You plan to run profitably rather than chase hypergrowth. Revenue-based capital complements a calm-company strategy: compound steadily, reinvest profits, consider dividends or founder buybacks.

Concrete examples:

- A niche B2B SaaS at 100k MRR with 85% gross margin uses a 300k RBF at a 1.5x cap, paying 4% of revenue monthly. The founder deploys funds into sales hires and modest marketing. Cap is reached in under 30 months, the team keeps 100% equity, and subsequent profit is unencumbered.

- An e-commerce brand with 2m annual revenue, strong unit economics, and seasonal peaks uses MCAs to fund inventory 4 times a year, with 8–12% factor fees over 3–4 months. The cost is higher than bank debt but cheaper and faster than equity. They rotate capital quickly, keep marketing budgets steady, and avoid stockouts.

In both examples, the thing that makes revenue-based work is a tight loop: cash in, convert to revenue with predictable yield, repay, repeat.

Where equity still wins

Equity is often better when your roadmap demands long periods of negative cash flow:

- Deep tech, biotech, or hardware with long R&D cycles and regulatory approvals.

- Marketplaces or consumer networks that require significant subsidy and scale before monetization.

- Winner-take-most markets where speed and land-grab tactics matter more than near-term unit economics.

- Lumpy enterprise sales with long sales cycles and implementation costs.

In these contexts, the flexibility that comes from not having to make payments is critical. Taking 5%–10% off the top each month can prevent you from hiring the team or building the product you need to win. If your cash curve is long and steep, selling equity aligns better with reality.

Understanding the true cost: IRR, factor fees, and covenants

Revenue-based providers often quote a multiple (cap) or a factor fee, not an annual percentage rate. To compare options, translate into an effective IRR based on expected repayment speed.

- Example: You receive 500k and repay 850k over 36 months. If payments were perfectly even (they won’t be), the IRR is roughly 19%–21%. If you repay faster (24 months), the IRR rises into the 30%+ range; slower (48 months) brings it down toward the mid-teens.

- MCAs with a 1.1x fee repaid over 4 months imply a very high APR if annualized; they are designed for short-term working capital, not multi-year projects.

Covenants and terms matter as much as price:

- Minimum payment floors: Some contracts require a minimum monthly payment even if revenue falls below expectations.

- Security interests: Lenders may file liens on assets or require personal guarantees for small businesses, especially with MCAs.

- Stacking restrictions: Contracts may limit your ability to take on additional debt-like instruments.

- Reporting and control: Monthly reporting, read-only banking access, or revenue verification requirements.

- Prepayment: Check whether you can repay early and at what discount; some tools impose a make-whole provision that limits savings from early payoff.

A seemingly cheap deal can become expensive if covenants amplify risk during a downturn.

Comparing specific instruments

-

Classic revenue-based financing (RBF)

- Use case: SaaS or subscription-like revenue

- Terms: 1.3x–2.0x cap, 2%–10% of monthly revenue

- Pros: Aligns with revenue, no equity dilution

- Cons: Cash drag; can lengthen time to profitability if margins are thin

-

Merchant cash advance (MCA)

- Use case: E-commerce and retail with credit card sales

- Terms: Daily or weekly remittances, factor fees (e.g., 1.08–1.2x) over 3–9 months

- Pros: Fast approvals, matched to sales cadence

- Cons: High effective APR; cash flow intensive; frequent remittances

-

Inventory and receivables financing

- Use case: DTC brands, wholesalers, agencies with invoice cycles

- Terms: Secured by inventory or invoices; rate depends on risk and collateral

- Pros: Cheaper than MCA; scales with assets

- Cons: Collateral and monitoring requirements; borrowing base limits

-

Shared earnings or founder buyback structures

- Use case: Calm, profitable businesses without a high-likelihood 100m exit

- Terms: Revenue or profit share until investors reach a target return; optional buyback at a formula price

- Pros: Preserves control, supports dividends and buybacks

- Cons: Complexity; may be unfamiliar to later-stage investors

-

Venture debt with revenue kicker

- Use case: VC-backed companies augmenting a round

- Terms: Interest + warrants or revenue share; covenants tied to cash runway or ARR

- Pros: Extends runway without much dilution

- Cons: Requires equity backing and strong metrics; downside risk if covenants are tripped

Each instrument solves a different problem. Match the tool to the job, not to a trend.

Risk, optionality, and exit paths

Equity can push you toward a binary outcome: go big or go home. Revenue-based structures broaden your optionality:

- Operate profitably and pay investor caps without needing an exit.

- Distribute dividends or founder salaries post-cap without constraints tied to preferred shareholders.

- Explore secondary sales or partial buybacks when the time is right.

On the other hand, revenue-based obligations can complicate a sale if the cap is unpaid, since acquirers may want to close out or refinance the obligation at closing. This is usually manageable but should be anticipated in deal planning.

Option value for founders is high: the ability to keep doors open to many outcomes is worth money even if it’s hard to price. Revenue-based options are an optionality-preserving middle path for companies that can repay them comfortably.

The tax angle and accounting treatment

While details vary by jurisdiction and structure, a few general considerations:

- Payments that look like interest or financing costs may be deductible as expenses, reducing taxable income. Profit-sharing distributions may not be deductible. MCA factor fees are typically treated as financing costs.

- On the balance sheet, some revenue-based obligations are recorded as debt with an effective interest method; others may be treated differently if there’s significant variability or equity-like characteristics.

- Equity has no repayment and no immediate tax deduction, but dividends are not deductible and may face double taxation in some structures.

Because treatment depends on contract specifics and local rules, coordinate early with your accountant to model after-tax cash flows. Two deals with identical nominal caps can have different after-tax costs.

Founder psychology and the lifestyle factor

Capital is not just math; it’s a set of expectations. Ask yourself:

- Do you want to optimize for control and calm compounding? Revenue-based capital lets you avoid board dynamics and growth-at-all-costs pressure.

- Does the idea of a monthly payment stress you out? If so, you may prefer the patience of equity.

- Are you building a company that could happily last 20 years? Non-dilutive structures line up with longevity and dividends.

- Do you thrive on aggressive sprints toward market dominance? Then equity may give you the psychological and financial runway you need.

Many founders underestimate the emotional tax of their capital stack. Choose a structure you can live with during both feast and famine.

How to choose: a decision framework

Work through this checklist and note the first constraint that snaps:

- Revenue predictability

- If at least 70% of next month’s revenue is reasonably forecastable from recurring contracts or repeatable sales, revenue-based options are viable.

- If revenue is highly lumpy or seasonal, model seasonality explicitly and consider inventory/receivables financing over a pure revenue share.

- Gross margin and CAC payback

- Margin ≥60% and payback ≤9 months? Good fit.

- Margin 40%–60% or payback 9–15 months? Proceed cautiously; cap the payment percent lower and lengthen duration.

- Margin <40% or payback >15 months? Equity or grants may be safer.

- Cash runway and minimum serviceability

- Compute minimum monthly payment across downside cases, including any floors. Could you cover it for 6 months in a row if growth stalls? If not, either reduce payment percent or avoid the instrument.

- Growth ambition and likely outcome size

- If you’re aiming for a 10–30m exit or durable profitability, revenue-based often dominates.

- If you’re shooting for 100m+ with heavy investment, equity will likely be cheaper and safer.

- Optionality and governance

- If you want to avoid board control and preserve dividends/buybacks, prefer revenue-based or buyback equity.

- If you need networked investor support and future follow-ons, equity with the right partners may bring more than money.

- Tax and accounting

- Model after-tax costs with your accountant. A 1.7x cap may cost less than you think if payments are deductible.

Make a simple matrix of three scenarios (base, downside, upside) and compute founder outcomes under both structures. The exercise itself often clarifies your gut.

Negotiating terms like a pro

Don’t accept the first term sheet. Small changes make big differences:

- Cap multiple: Lower the cap to 1.3x–1.6x for shorter-duration uses (marketing sprints) and accept a slightly higher revenue share. For longer-term uses (hiring, product), a 1.7x–2.0x cap may be appropriate at a lower percentage.

- Revenue percentage: Match to margin. For high-margin SaaS, 3%–6% is common. Negotiate a step-down as you hit revenue milestones.

- Payment floors and ceilings: Avoid hard floors in seasonal businesses. Consider a minimum only after 6 months and set a maximum monthly payment to protect cash in surge months.

- Prepayment: Ask for a sliding prepayment discount. For example, repay within 12 months at 1.2x; within 24 months at 1.4x, etc.

- Covenants: Push back on personal guarantees and broad liens if possible. Limit collateral to receivables or specific assets.

- Reporting: Agree on monthly reporting and read-only access, not intrusive controls.

- MFN and flexibility: Include most-favored-nation clauses for future instruments and avoid anti-stacking provisions that could trap you.

- Clarity on definitions: Precisely define revenue used for calculations (gross vs. net of refunds, taxes, chargebacks) and how seasonality is treated.

Run two or three competing processes. Having options is the strongest negotiating lever you can create.

Case studies: calm SaaS vs. spiky marketplace

Case 1: Calm B2B SaaS

- Profile: 150k MRR, 85% gross margin, 3% monthly logo churn, CAC payback 7 months.

- Need: 600k to hire 3 sales reps and 2 engineers; conservative plan to reach 250k MRR in 18 months.

- Option A (RBF): 600k at 1.6x cap, 5% of revenue. Payments start at 7.5k/month and scale to around 12.5k as MRR grows. Cap likely reached in ~32 months. After payoff, company throws off 1–1.5m in annual free cash flow. Founder retains 100%.

- Option B (Equity): 600k at 6m pre (post 6.6m), selling ~9.1%. If the company sells for 25m in 4 years, founder cost is ~2.275m; if it never sells and instead distributes profits for 10 years, equity cost is opportunity cost and governance overhead.

Result: Given predictability and margins, RBF preserves control, the cash drag is manageable, and the likely outcome is sub-100m. RBF dominates.

Case 2: Spiky two-sided marketplace

- Profile: 40k monthly gross merchandise value at 10% take rate (4k revenue), 30% month-to-month volatility, thin margins early, high subsidy required to build supply and demand.

- Need: 1.5m to reach liquidity in 6 initial markets.

- Option A (RBF): Practically unserviceable. Even 5% of revenue is trivial relative to the cash burn; a payment floor would crush runway.

- Option B (Equity): Best fit. No repayment pressure; can invest to hit network effects. Later, venture debt can extend runway once revenue stabilizes.

Result: Equity is superior because the business needs slack and patience more than it needs a non-dilutive label.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Stacking short-term MCAs: Multiple advances can compound into daily remittances that exceed 20% of sales, starving operations. Avoid stacking unless your cash conversion cycle is ultra-short and predictable.

- Ignoring seasonality: A 6% revenue share during Q4 may feel fine, but the same percentage in a weak Q1 with floors can trigger covenant issues. Model month-by-month.

- Overestimating growth: If your repayment math assumes 10% monthly growth and you hit 3%, payments could drag for years and tie up your borrowing capacity.

- Misdefining revenue: Contracts that define revenue as gross cash collected including taxes and shipping can inflate payments unfairly. Nail the definition.

- Personal guarantees: For small businesses, some providers will push for them. That converts business risk into personal risk. Negotiate them out or cap exposure.

- Not planning for exit: If you might sell in 12–24 months, ensure the agreement allows payoff at closing without a punitive make-whole.

A blended approach: stacking capital without breaking cash flow

Many of the best outcomes come from mix-and-match strategies:

- Customer prepayments and annual plans: Offer a 10%–15% discount for annual prepay. This is cheap capital from your happiest customers.

- Small equity + RBF: Sell 5%–8% equity to extend runway and use RBF to fund working capital. The small dilution buys safety while the RBF preserves upside.

- Grants and tax credits: R&D credits and grants can reduce burn without strings.

- Inventory financing for goods; RBF for marketing: Finance each component with the instrument that mirrors its cash cycle.

- Founder salary discipline: In early repayment periods, modest founder salaries reduce pressure and optionality expands once caps are paid.

Design your capital stack like your product: for fit, not fashion.

Modeling your own numbers: a quick how-to

Open a spreadsheet and set up three tabs: assumptions, monthly model, outcomes.

- Assumptions: Starting MRR, gross margin, churn, CAC payback, growth rates, payment percent, cap multiple, operating expenses, seasonality factors.

- Monthly model: Project revenue, gross profit, operating expenses, revenue-based payment (as a % of revenue subject to floors/ceilings), cash balance. Include a downside case with growth at half the base rate and a 10% one-time revenue hit.

- Outcomes: Time to cap payoff, total cash paid, implied IRR to investor, months of runway added, EBITDA margin trajectory, founder ownership vs. equity scenario.

Rules of thumb for the model:

- Keep revenue-based payments under 10% of gross profit on average; temporarily exceeding is fine if you have cash buffers.

- Target cap payoff within 24–36 months for marketing or inventory uses; 36–48 months for talent and product investments.

- Build a cash minimum equal to 3 months of operating expenses; if payments breach that buffer in downside, revisit terms.

A transparent model is also a negotiation tool; you can show lenders or investors why certain terms make the relationship healthier.

Provider landscape and picking a partner

You’ll encounter different flavors of providers depending on your business:

- SaaS-focused RBF: Providers who underwrite ARR/MRR, churn, and retention. They often integrate with billing and accounting tools.

- E-commerce working capital: Providers tied into payment processors or storefronts, underwriting ad performance and inventory turns.

- Calm-company funds: Investors offering shared earnings or buyback structures, aligning with long-term profitable growth.

When choosing a partner, look beyond the rate:

- Underwriting approach: Do they understand your model, or are they forcing you into a generic template?

- Flexibility: Will they adjust payment percent if you hit a temporary snag? Are there structured step-downs as you grow?

- Reputation: Talk to portfolio founders about reporting burden and behavior during down months.

- Speed vs. diligence: Faster is not always better; thoughtful underwriting often yields fairer terms.

The best partner cares about your cash conversion cycles as much as you do.

Are revenue-based options better than equity for bootstrapping?

If your business has:

- High margins, stable recurring revenue, and short payback loops,

- A likely outcome of profitable independence or modest exit,

- A founder team that values control and optionality,

then revenue-based options are often better than equity. They minimize dilution and institutional pressure while matching repayment to your success.

If your business must:

- Absorb long, loss-making phases before revenue stabilizes,

- Pursue network effects or regulated markets with uncertain timelines,

- Race competitors in winner-take-most environments,

then equity is often the smarter path. It buys patience and flexibility that revenue-sharing obligations can’t.

There is no absolute better. There is only fit.

Final tips you can use this week

- Get three quotes: For any revenue-based offer, get two more. Compare caps, percentages, floors, prepayment rights, and collateral.

- Define revenue carefully: Net of refunds, taxes, chargebacks; specify signup fees, services, and non-recurring items.

- Stress test: Rebuild your forecast with revenue 30% below plan for 6 months. If your cash hits zero with current terms, renegotiate.

- Prepayment plan: If things go well, when would you prepay? Negotiate a schedule upfront.

- Communicate: Share monthly KPI dashboards with your provider. Good transparency buys goodwill when you need flexibility.

- Keep an investor update list: Even if you avoid equity now, build relationships. Future you might want options.

Choosing capital is part finance, part strategy, and part self-knowledge. Treat it like product-market fit: test, measure, iterate. With clear eyes on your cash conversion cycle and a willingness to negotiate terms that reflect your reality, revenue-based options can be a powerful ally in the bootstrapper’s toolkit.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts