Comparing Medieval Guilds With Modern Day Secret Groups

13 min read An in-depth comparison revealing the parallels and contrasts between medieval guilds and modern secret groups, exploring their roles, influence, and evolution in society. (0 Reviews)

Comparing Medieval Guilds With Modern Day Secret Groups

When you hear the word “guild,” visions of bustling medieval towns likely come to mind—merchants bartering under ornate wooden signage, blacksmiths hammering in smoky workshops. Now, imagine whispers in candle-lit rooms, coded handshakes, and strict oaths of secrecy: the hallmarks of today’s clandestine societies. On the surface, medieval guilds and modern secret groups seem to belong worlds—and centuries—apart. But look closer, and the threads that connect them tell a compelling story about continuity, power, and human nature’s impulse to organize.

In this article, we embark on a surprising journey, comparing two distinct phenomena: the medieval guild and the modern secret group. By exploring their missions, organizational structures, cultural impacts, and the mysteries veiling both, we reveal how ancient and modern societies shape—and are shaped by—exclusive organizations. Whether you’re a history buff, a lover of intrigue, or simply curious, read on to uncover the fascinating parallels and contrasts between these two worlds.

The Medieval Guild: Pillar of Community and Economy

The Rise of the Guilds

Medieval guilds flourished from the 11th through the 16th centuries—a transformative era for Europe. As feudalism began breaking down and towns swelled with commerce, the need for organization and mutual support among tradesmen grew dramatically.

Guilds emerged as formal associations of artisans or merchants who wielded collective power. These were not merely clubs; they formed the beating heart of city commerce, trade regulation, and even local governance.

**"No tradesman was allowed to practice his craft within a town except as a member of a gild." — W. J. Ashley, An Introduction to English Economic History and Theory (1888)

Organization, Hierarchies, and Rituals

Guilds were meticulously structured. Most included three ranks:

- Apprentices: Young learners, often as young as 12, bound by contract to a master.

- Journeymen: Skilled workers who earned wages and traveled to gain experience.

- Masters: Elite craftsmen who could own workshops, train apprentices, and participate in governance.

Entry often involved elaborate ceremonies, oaths, or symbolic feats (like producing a "masterpiece" to demonstrate skill). Strict rules governed everything from trading hours to pricing and quality standards.

The Power and Influence of Guilds

Guilds operated like early regulatory bodies, often rivaling city councils in influence. They:

- Set standards for production and training

- Administered charity and looked after members in need

- Arbitrated disputes within the trade

- Held religious or festive processions, reinforcing their bond to civic and spiritual life

Guild halls—sturdy stone or timber buildings—served as visible affirmations of their status. In many towns, guild insignias adorned shields and banners, symbolizing both economic and social clout.

Exclusivity, Secrecy, and Mutual Aid

Guilds were exclusive by nature: only approved members (usually men, though a few all-female religious orders existed) could work or teach their trade. Non-members were considered threats to both quality and control.

The "craft secrets"—techniques, formulations, or trade connections—were closely guarded. For example, Venetian glassmakers walled off their secrets so tightly that teaching foreigners was punishable by death.

Mutual support was paramount. Ill members received aid, funeral expenses were covered, and members’ families benefitted from a form of primitive social security—a remarkable precursor to modern mutual insurance.

Legacy and Decline

By the 17th century, economic changes and new industries challenged guild monopolies. Governments grew wary of their power, issuing reforms or outright suppressing them. Yet guilds laid the foundation for today’s professional associations, unions, and chambers of commerce.

Modern Secret Groups: From Mystery to Modern Power

The Emergence of Secret Societies

Modern secret groups—sometimes called "secret societies" or "fraternal orders"—trace their roots to various sources. Some began in the Enlightenment-era milieu, while others arose out of collegiate tradition, political movements, or spiritual quests.

Few names spark more imagination than the Freemasons, the Illuminati, Skull and Bones, Bilderberg Group, or the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Each offers its own blend of mystery, selective membership, and influence.

Structure, Ritual, and Identity

Just like guilds, modern secret societies operate through layered hierarchies:

- Initiates/Neophytes

- Members or "brothers"

- Elders or inner circles (such as Freemason Masters or Skull and Bones alumni board)

Initiation rituals—filled with oaths, mysterious regalia, and sometimes arcane symbolism—cement loyalty and create a sense of belonging. Skulls, keys, and coded gestures recall the guild’s penchant for iconography and ceremony.

"Secret societies are the most powerful and most lasting voluntary organizations in the history of the world." — Richard B. Spence, University of Idaho

Mission and Influence

Modern secret groups have no single purpose. Some, like the Freemasons, emphasize philanthropy, moral virtue, and fellowship. Others, such as collegiate societies, often aim at consolidating elite social circles and influencing future leaders. Conspiracy theories have fueled the mystery—alleging these groups hold sway over politics, finance, and societal change.

Real Influence Examples:

- Skull and Bones Society (Yale): Numerous alumni became U.S. Presidents, Senators, Supreme Court Justices, and business magnates.

- Freemasonry: Many signers of the U.S Constitution, including George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, were Freemasons—a testament to the group’s political and cultural capital.

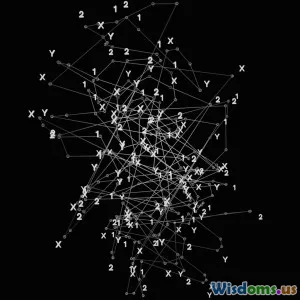

Secrecy, Code, and Symbolism

Secrecy is the signature feature. Members pledge confidentiality, and group signs, passwords, and rituals create strong boundaries between insiders and outsiders. While actual state secrets are not usually at play, the mystique fosters delight, rumor, and allegiance.

Secret societies often borrow from a shared visual lexicon—pyramids, eyes, hands, swords. This iconography ties them to an ancient past, weaving a narrative of timeless wisdom and chosen elects.

Mutual Support in Modern Guise

In the absence of medieval apprenticeship, modern secret groups deliver value through:

- Career networking (exclusive job openings, influential recommendations)

- Social capital (invitations to elite events, marital alliances)

- Community projects and charity (the Shriners, Alfalfa Club)

Just as guilds once shielded members during illness, secret groups foster "old boys’ networks"—still controversial for limiting access but often effective at supporting initiates.

Parallels: What Medieval Guilds and Modern Secret Groups Share

1. Exclusive Membership and Controlled Access

Both institutions restrict entry, requiring recommendations, sponsorship, and proof of commitment. This exclusivity reassures members of mutual loyalty and upholds group integrity.

- Guilds: Only trained, vetted individuals could wield a trade’s benefits.

- Secret Groups: Membership criteria include legacy connections, demonstrated loyalty, or moral criteria.

2. Shared Rituals and Symbolism

Ceremonial objects, processions, secret handshakes: these features invite participants to step into a parallel reality, unified and distinct from the outside world. Medieval guilds passed around chalices in celebration; today, societies exchange rings, specific regalia, and cryptic mottos.

3. Knowledge Control

Guarding trade secrets or esoteric knowledge sets these organizations apart, granting them advantages in the market or society. In the case of guilds, knowing dye recipes or forging techniques was a ticket to livelihood. Secret groups are said to protect "hidden wisdom"—even today, mysterious manuscripts and coded documents fascinate experts and outsiders alike.

4. Social Support and Security

Both offered support in times of need—whether burial expenses in the 14th century or lucrative introductions in a Wall Street boardroom. Mutual aid creates loyalty and further cements group solidarity.

Contrasts: Changing Contexts and Critically Different Outcomes

1. Public vs. Private Roles

- Guilds: Openly shaped city life, hosted ostentatious festivals, and directly influenced economic policies.

- Modern Secret Groups: Prefer discretion, often denying or downplaying their existence. Some (e.g., the Rosicrucians) carefully curate secrecy as a brand.

2. Function: Economic Necessity vs. Social Prestige

Guilds addressed core survival needs: skills training, price setting, pensions. Their existence ensured livelihoods. By contrast, most modern secret societies center around social capital, ideological goals, or ceremonial enjoyment rather than practical material benefits.

3. Legal and Social Standing

Guilds were legal entities with civic responsibilities and obligations, recognized and empowered by authorities. Secret societies’ legal recognition varies. Some are registered associations, but others, like the Bilderberg Group, operate informally, skirting publicity and regulation.

4. Adaptation to Changing Technology

Medieval guilds fared poorly when sweeping innovations threatened their craft monopolies, as in the rise of industrial capitalism or automation. Modern secret groups remain viable by shifting towards personal development, network influence, or sociopolitical engagement. Many have leveraged digital communication (such as online "deep web" forums or private WhatsApp channels) to maintain secrecy in a transparent age.

5. Diversity and Inclusion

Guilds overwhelmingly excluded women, non-Christians, and outsiders. Prostitutes, tanners, or low-status trades were sometimes denied entry. Today’s secret societies, though slow to adapt, face added scrutiny for gender, racial, and economic exclusivity, leading to incremental reforms or more open splinter groups.

Enduring Mystique: Why Societies Love Secrecy

Both medieval and modern groups tap into a powerful human impulse—the desire for belonging with a hint of mystery. Group therapy expert Irvin Yalom explains that being part of a select "in-group" not only brings material reward, but confers psychic satisfaction, from improved self-esteem to meaning-making through shared mythology.

- In the Middle Ages, joining a guild promised apprentices not just a job, but a clear place in society’s hierarchy.

- In today’s complexity, secret organizations offer members clarity amid social flux, personal connections in an impersonal world.

Case Studies: Real-World Examples Across Eras

The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths (London)

- Founded: 1327

- Impact: Regulated standards for gold and silver, influencing currency stability; its emblem appears on British coins to this day.

- Secrecy: Master jewelers’ formulas were fiercely guarded.

Skull and Bones Society (Yale)

- Founded: 1832

- Impact: A disproportionate number of U.S. Cabinet members, Senators, and business leaders trace roots to “the Tomb.”

- Secrecy: Members never discuss society business, and annual initiations are legendary for their symbolism.

Freemasonry

- Founded: Ancient origins, formally codified in 1717

- Impact: George Washington, Simon Bolivar, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart counted as members. Instrumental in revolutionary thought and public philanthropy.

- Secrecy:

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in History of Secret Societies

Popular Posts