Do Eastern and Western Sacred Texts Agree on Compassion?

17 min read A comparative look at how Eastern and Western sacred texts define and promote compassion across religions and cultures. (0 Reviews)

Do Eastern and Western Sacred Texts Agree on Compassion?

Across centuries and civilizations, compassion has simmered at the heart of religious aspirations. But is it just a surface-level sentiment that appears in sacred scriptures, or do the texts of the East and West truly share common ground on this cherished virtue? Let’s dig deeply, examining the texts themselves and unearthing what these rich traditions truly say—how they converge, where they differ, and how these insights might transform how we act with kindness in our modern world.

Sacred Texts and the Idea of Compassion

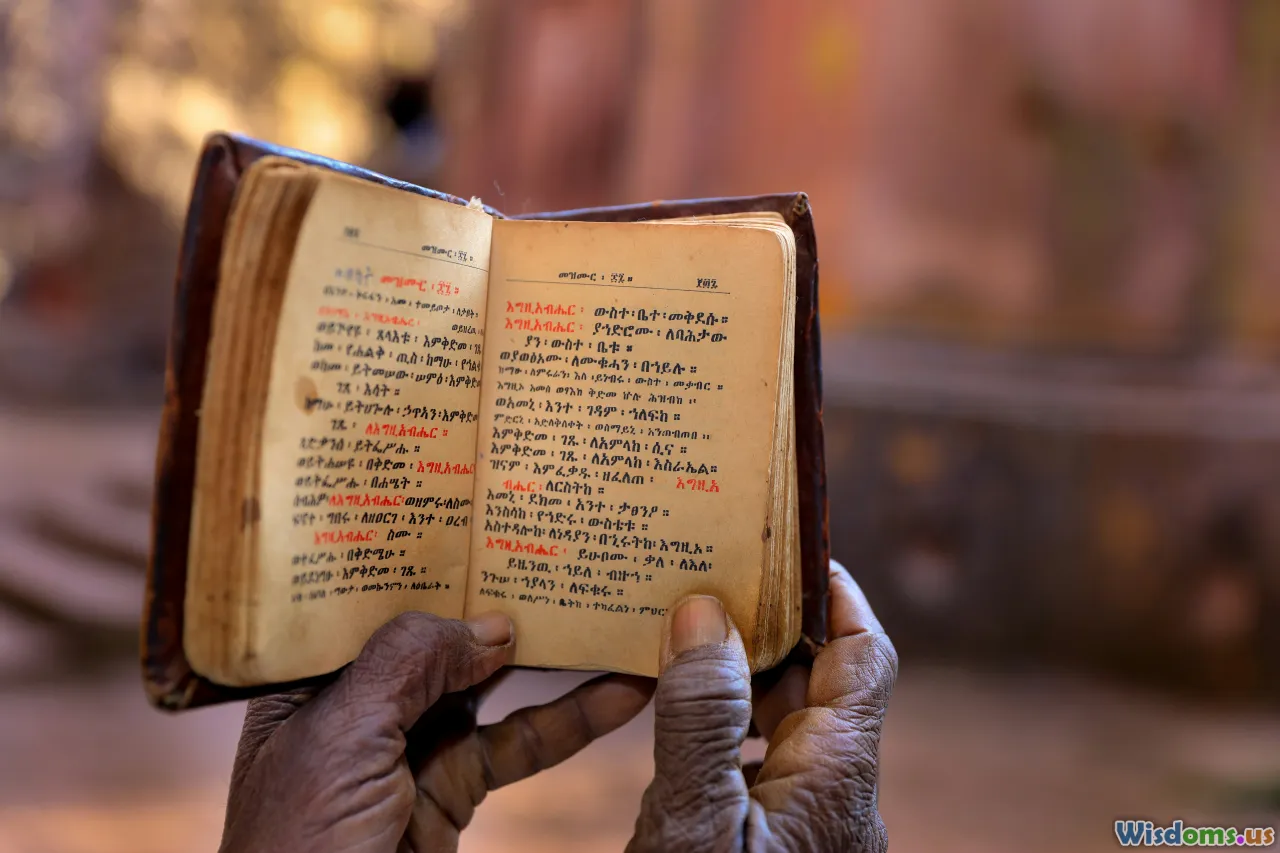

To grasp where Eastern and Western sacred writings align or diverge, we first need to clarify their central sources. Eastern traditions typically refer to the Vedas and Upanishads (Hinduism), the Tipitaka (Buddhism), and the Dao De Jing (Daoism), among others. Western spirituality looks mainly to the Tanakh/Old Testament and the New Testament (Christianity), as well as the Qur’an (Islam). Despite cultural chasms and linguistic divides, a striking theme echoes through the corridors of these canons: a profound emphasis on compassion—bearing suffering with others and acting to alleviate it.

Eastern Lens: Buddhist and Hindu Texts

Buddhism makes compassion (karuṇā) a foundational practice, elevated next to wisdom. In the Dhammapada—one of Buddhism’s most widely read texts—one passage states:

“All tremble at violence; all fear death. Putting oneself in the place of another, one should not kill nor cause another to kill.”

Here, active identification with the pain of others underpins Buddhist conduct. Similarly, ancient Hindu texts like the Mahabharata enjoin ahimsa (non-violence) and dayā (compassion) as supreme virtues. Because all beings are seen as interconnected in Brahman, compassion is demanded as a recognition of our shared divinity.

Western Lens: Abrahamic Scriptures

The Bible, both Old and New Testaments, abounds with calls to love and mercy. The prophet Micah insists that what is good is to "do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God" (Micah 6:8). In the New Testament, Jesus centrally proclaims, “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:31) and presents the parable of the Good Samaritan to dramatize radical acts of kindness across boundaries of enmity. Equally, the Qur’an is replete with references to God as ‘the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful’ (ar-Rahman, ar-Rahim) and urges, “And be kind to parents, relatives, orphans, the needy, the near neighbor, the neighbor farther away…” (Qur’an 4:36).

Across both hemispheres, then, foundational scriptures promote not just feeling compassion—but doing compassion through ethical action.

Analysing Key Teachings: Parallels in Compassion

If compassion is common to Eastern and Western sacred texts, do they emphasize it similarly? When we peel back the surface, uncanny parallels emerge:

Universal Ethic of Reciprocity

Both traditions offer some form of the Golden Rule, advocating painless living for others as for oneself. In Christianity, Jesus summarizes the Law and the Prophets in a sentence: “Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them” (Matthew 7:12). Confucius offers a parallel principle over a century earlier: “Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself” (Analects 15:24). Judaism—through Leviticus 19:18—commands, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” In the Mahabharata: “This is the sum of duty: do not do to others what would cause pain if done to you.”

This symmetry in reciprocity, an empathetic ‘other-mindedness,’ anticipates and counters harm before it even begins, making compassion a practical ethic for daily conduct.

Compassion for the Stranger and Outcast

Both spheres emphasize compassion for those marginalized or suffering. In the Torah, justice for the foreigner is explicit: “You are to love those who are foreigners, for you yourselves were foreigners in Egypt” (Deuteronomy 10:19). The story of the Buddha’s enlightenment centers on ending universal suffering—not merely his own. Moreover, in the Qur’an, the emphasis on charity (zakat) and empathy for the impoverished is deemed fundamental; “Whoever saves one life, it is as if he had saved all mankind” (Qur’an 5:32).

Spiritual Progress Tied to Compassion

Compassion isn't only a good deed in these texts—it’s a transformative spiritual path. Eastern philosophies often insist that one cannot attain enlightenment (moksha, nirvana) without dissolving ego via compassion. The Buddha insists, “Just as a mother would protect her only child at the risk of her own life, even so, let one cultivate a boundless heart towards all beings.”

Meanwhile, in Christianity, salvation is melded to mercy and self-giving love. The parable of the Sheep and the Goats (Matthew 25:31-46) measures one’s worth by practical compassion: “I was hungry and you gave me food… as you did it to one of the least of these… you did it to me.”

Contrasts and Nuances: Varieties in Compassionate Thought

For all their similarities, Eastern and Western traditions sometimes frame compassion in distinct ways, laden with their own philosophical baggage and spiritual goals.

Compassion as Interconnectedness vs. Obedient Mercy

Eastern conceptions, especially Buddhist and Hindu, often root compassion in an ontological unity—the belief that separation is illusory and true seeing connects us to the suffering of all beings. Thus, compassion is as much about awareness and identification as about duty. Thich Nhat Hanh, a modern Buddhist monk, phrases it: “Compassion is a verb.”

In Abrahamic religions, while empathy is crucial, compassion can also align with obedience to God’s commandments or covenant—structured by narrative and law. Mercy, therefore, may be interpreted as imitating divine benevolence or justice (as in the Hebrew term chesed, often translated as ‘lovingkindness’).

The Goal of Compassion: Liberation or Restoration?

In many Eastern systems, compassion serves as a means to liberation (nirvana in Buddhism, moksha in Hinduism)—to remove suffering altogether through spiritual insight. This outlook, oriented towards transcending the cycle of suffering (samsara), sees compassion as freeing both oneself and others.

By contrast, Western scripts often focus on redemption, reconciliation, or restoration. Biblical compassion targets the world’s brokenness, attempting to restore right relationships with God and neighbor—sometimes irrespective of suffering itself. Compassion, here, redeems rather than merely releases.

Hierarchies of Compassion: Inclusive or Exclusive?

Traditions also vary in the scope of commanded compassion. Buddhist teachings press for boundless compassion, extending care to "all sentient beings" without distinction. Jesus, in the New Testament, stretches love to encompass even one’s enemies (Matthew 5:44). However, certain passages in the Hebrew Bible and Qur’an balance mercy with justice and prioritize the community of faith.

The differences, then, are sometimes in the scope and the grounding of compassion—but not, it seems, its importance.

Real-World Case Studies: Compassion in Action

Beyond doctrinal musings, do sacred texts shape compassionate practice? Throughout history, religious communal movements have leaned deeply on their founding texts to inspire radical acts of kindness.

Mahayana Buddhism’s Bodhisattva Ideal

In Mahayana Buddhism, the bodhisattva vows to postpone personal enlightenment until all beings are liberated from suffering. Texts like the “Lotus Sutra” emphasize “great compassion” (maha-karuṇā), a philosophy that animates everything from Dalai Lama’s peace activism to the diverse global network of Buddhist orphanages and hospitals.

Western Monasticism and Social Care

Christian monasteries, guided by the Gospels’ call to clothe the naked and feed the hungry, pioneered hospitals, leprosaria, and shelters in Medieval Europe—even when such acts brought social scorn. The Pauline notion that “if I have no love, I am nothing” (1 Corinthians 13:2) energized much of the modern era's healthcare and charity.

Islamic Zakat and Relief Foundations

Islam's Five Pillars include zakat (charitable giving), stressing routine, calculated mercy. Across North Africa and Asia, mosque-based charities provide food, education, and medical care. The mandate comes straight from texts—the Qur’an insists, over a hundred times, on compassion towards orphans, widows, and travelers.

Hindu NGOs and Global Relief

Organizations like the Ramakrishna Mission in India draw on Swami Vivekananda’s call for “practical Vedanta”—compassion through selfless service. Inspired by the Bhagavad Gita’s dictum to act without attachment but in service to all beings, millions labor under a devotional ethic: “Work and worship are one.”

Whether sheltering refugees, tending the sick, or feeding the poor, sacred texts serve as both rallying cry and measure for radical acts of compassion.

Compassion as a Modern Calling: Insights from Tradition

Why, in a world rife with conflict and cynicism, do these traditions still matter? Here are four ways ancient wisdom continues to enrich modern compassion:

1. Expanding the Compassion Circle

The Buddhist and Jain ideal of care for all living beings has encouraged contemporary ethical vegetarians and environmental activists alike. The encyclical Laudato Si’ from the Catholic Church or Pope Francis’ statements echo ecological compassion remarkably similar to Hindu and Buddhist earth-stewardship themes.

2. Deepening Empathic Skills

Compassion in Eastern traditions is a practice—a muscle. The Metta (loving-kindness) meditation encourages the outward wish: “May all beings be happy; may all beings be at peace.” Mindfulness-based stress reduction, inspired partly by Buddhist practice, is now mainstream among therapists and social workers aiming to cultivate sustained, genuine empathy and prosocial behavior.

3. Anchoring Social Justice

Western sacred texts have inspired individuals and entire movements—from abolitionists to civil rights campaigners—to make compassion not just an aspiration but a policy. The Quaker saying “Let us see what love can do” carried anti-slavery, women’s suffrage, and contemporary refugee aid initiatives.

4. Healing Divisions through Shared Values

Despite their differences, East and West agree that true religion is hollow if it fails to manifest in practical care for others. Interfaith dialogues often start by citing the Golden Rule or reciprocal injunctions on compassion, sowing understanding across divides. Faith-rooted organizations as diverse as the Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation and global Caritas draw on the same ancient textual mandates to respond to floods, earthquakes, and conflicts.

Facing Contemporary Pitfalls: Moving from Text to Action

Though the calls to compassion in scripture are clear, organizations and communities sometimes fall short. Sacred texts can be misused, weaponized to justify exclusion or violence despite their central messages. How, then, can we keep textual compassion vibrant and actionable?

- Context Matters: Understanding texts within their historical and social setting clarifies the spirit behind the rules.

- Avoid Legalism: When compassion becomes performative or legal, it can hollow out its original spirit. The prophetic voices in both traditions warn forcefully against empty ritual bereft of heartfelt mercy.

- Practice and Reflection: Tools like daily readings, group reflections, and charity initiatives help reconnect warm sentiments with hands-on help.

- Community Accountability: Faith communities do well when they ask not “Are we worshiping the right way?” but “Who have we fed, clothed, comforted today?”

Recent research (such as Harvard’s Pluralism Project) shows that religious groups which ground their identities in compassionate service build not only a better public witness—but also deeper communal bonds and resilience.

Why Ancient Lessons Matter More Than Ever

While sacred texts arose in radically different societies, their gravitational pull toward compassion bridges East and West. Whether it’s the Buddhist call for boundless loving-kindness, the Jewish obligation to love the "stranger," the Christian model of self-sacrificing love, or the Islamic mandate for constant acts of mercy, texts invite us to see the face of the Holy in those who suffer. They direct us not simply to possess compassionate thoughts but to make compassion a practice—creative, binding, and urgent.

In a digital, divided age, returning to these passages is not regression but remembering the foundation on which civilized societies are built. If ancient voices—Buddha, Jesus, Muhammad, Confucius—converge on one point, it’s that the measure of authentic faith is not just belief, but how widely and deeply we extend compassion.

Let’s keep listening—and not just with our ears, but with our hands and hearts, translating ancient wisdom into daily radical kindness.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Sacred Texts & Wisdom

Popular Posts