Dreams Decoded Are They the Brain’s Problem Solvers

9 min read Explore how dreams act as the brain’s problem-solving tool, decoding mysteries behind sleep and cognition. (0 Reviews)

Dreams Decoded: Are They the Brain’s Problem Solvers?

Introduction

Every night as we drift into the slumber of sleep, a mysterious realm unfolds — our dreams. From bizarre, vivid landscapes to seemingly ordinary scenarios replaying in our minds, dreams have captured human imagination for millennia. But beyond their poetic allure, could dreams actually serve a deeper functional purpose? Recent scientific advances increasingly suggest that dreams are not just random brain static during sleep but sophisticated mental simulations that help solve problems, integrate experiences, and enhance creativity.

This article dives into how dreams contribute to problem-solving processes in the brain, exploring the mechanisms involved and analyzing real-world examples and research findings that highlight their significance.

The Science of Dreaming: More Than Random Images

What Happens in the Brain During Dreams?

Dreaming primarily occurs during the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) stage of sleep, a phase when brain activity mimics wakefulness but the body remains largely paralyzed. During REM sleep, the brain’s limbic system — critical for emotions and memory — becomes highly active. Simultaneously, parts of the prefrontal cortex responsible for rational decision-making show reduced activity, which explains why dreams can appear illogical yet emotionally poignant.

Neuroscientists have discovered that these unique brain states may enable the exploration of novel solutions by loosening rigid cognitive patterns.

Dreams and Memory Consolidation

A substantial body of research connects dreaming with memory consolidation, particularly the process of transferring temporary memories from the hippocampus to long-term storage in the cortex. This transfer often involves extracting the gist or patterns from daily experiences, allowing useful information to be retained and irrelevant details discarded.

Memory scientist Matthew Walker notes, "Dreaming facilitates associative thinking. It enables us to connect disparate pieces of information in ways we might not consciously consider."

This dropdown filtering is essential for problem-solving because it helps the brain recognize and recombine relevant data into creative insights.

Dreams as Natural Problem-Solvers

The Theory of ‘Off-line’ Problem Solving

Researchers suggest dreams provide a safe mental space for 'offline' problem solving, where the brain can simulate challenges without real-world consequences. Unlike wakeful problem solving where logic and rules dominate, dreaming allows free associative thinking unbound by current constraints.

A classic example comes from the chemist August Kekulé, who famously reported a dream of a snake seizing its own tail, which helped him conceptualize the cyclic structure of benzene — a breakthrough in chemistry.

Empirical Evidence of Dream-Enhanced Creativity

Several experiments have tested the brain’s problem-solving capacity post-sleep or after induced dreaming. One seminal study by psychologist Deirdre Barrett asked participants to go to sleep with specific problems in mind; over half reported dreams related to the problem, and many awoke with novel approaches.

Another research team demonstrated that REM sleep improves tasks that require creative integration, such as combining remote elements or finding innovative analogies. This suggests that dreams foster not only emotional integration but also pragmatic cognitive breakthroughs.

Emotional Problem-Solving in Dreams

Dreams also tend to focus on emotionally charged problems that might be difficult to confront consciously. By reprocessing emotional conflicts and fears within a dream environment, individuals may emerge with greater clarity and reduced anxiety.

A vivid insight emerged during studies on people undergoing psychotherapy: their dreams often simulated scenarios related to personal growth and emotional problem-solving, implying that dreaming is a crucial part of mental health restoration.

Mechanisms That Support Dream-Based Problem Solving

Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis Revisited

Initially, the activation-synthesis hypothesis posited dreams were the brain’s attempt to make sense of random neural signals during sleep. However, newer perspectives suggest that although dreams originate from spontaneous activity, the brain actively synthesizes this into meaningful narratives that can lead to problem solving.

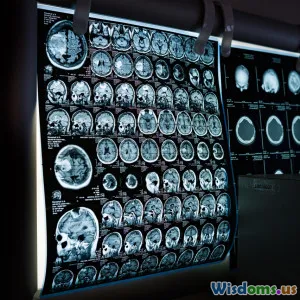

Neural Spotlight on Creativity and Insight

Neuroscientific techniques like fMRI and EEG have shown increased communication between brain areas responsible for memory, emotion, and higher-order thinking during dreaming. This neural interplay closely resembles what underpins the 'insight effect' — sudden solutions appearing in conscious thought.

The Role of Dopamine

Dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to reward and motivation, spikes in the brain during REM sleep. This chemical boost may incentivize novel associations forming in dreams, thus enhancing creative problem-solving power.

Real-World Applications and Insights

Dream Journals and Problem Solving

Writers, inventors, and scientists keep dream journals to capture fleeting ideas. Examples include Nobel laureate Otto Loewi, who reportedly discovered the chemical basis for neurotransmission following a dream.

A contemporary approach encourages people to train themselves to pose daily questions before sleep, enhancing their ability to retrieve solutions from dreams — a practice aligned with lucid dreaming techniques.

Therapeutic Use of Dream Analysis

Clinicians use dream interpretation to unlock subconscious barriers, helping patients address unresolved conflicts. While Jung and Freud popularized this method, recent psychology embraces dreams as therapeutic spaces where problem-solving can naturally unfold.

Improving Learning & Performance

Studies reveal that problem-focused dreams can improve performance in tasks learned before sleep, from complex math to sports. This underscores how targeted dreaming can be a valuable tool to improve skill acquisition and adaptive thinking.

Conclusion

Dreams have evolved from enigmatic nighttime episodes to increasingly recognized facilitators of intricate cognitive processes. The evidence points compellingly to their role as the brain’s innate problem solvers — leveraging emotion, memory, and creativity in a blended matrix that nurtures inspiration and resolution.

Investing conscious effort into understanding and harnessing dreamwork offers transformative potential: unlocking new ideas, managing emotional challenges, and enriching our learning curves. Dreams, decoded, demonstrate a profound truth about the human mind — it tirelessly works even when we rest, forging solutions beyond the grasp of waking thought.

Next time you wake up pondering a strange dream or a sudden insight born from sleep, remember — your brain might be solving problems for you, one dream at a time.

References:

- Walker, M. (2017). Why We Sleep. Scribner.

- Barrett, D. (2001). The Committee of Sleep: How Artists, Scientists, and Athletes Use Dreams for Creative Problem Solving.

- Hobson, J. (2009). REM Sleep and Dreaming: Towards a Theory of Consciousness during Sleep.

- Cai, D. J., Mednick, S. C., Harrison, E. M., Kanady, J. C., & Mednick, S. A. (2009). REM, not incubation, improves creativity by priming associative networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(25), 10130-10134.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Mental Health

Popular Posts