How Gobekli Tepe Challenges Our View of Civilization

7 min read Explore how Göbekli Tepe rewrites history and reshapes our understanding of early civilization origins. (0 Reviews)

How Göbekli Tepe Challenges Our View of Civilization

Göbekli Tepe stands as one of the most remarkable archaeological discoveries of the 21st century. Uncovered in southeastern Turkey, this ancient site has turned long-accepted assumptions about human civilization upside down. Predating Stonehenge by over 6,000 years and the Egyptian pyramids by nearly 7,000 years, Göbekli Tepe forces historians and archaeologists alike to reconsider how and when organized human societies emerged.

Rediscovering Human Beginnings: An Introduction to Göbekli Tepe

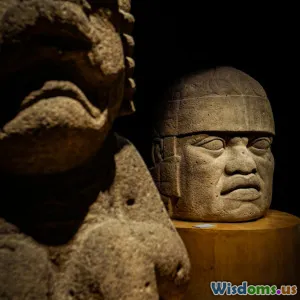

Dating back approximately 11,600 years, Göbekli Tepe is widely regarded as the world’s oldest known megalithic structure. Excavations in the 1990s, led by German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt, revealed massive T-shaped limestone pillars arranged in circular enclosures, adorned with intricate carvings of animals and abstract symbols. The sophistication of these constructions and symbolic artworks was unexpected for a time previously thought dominated by small, mobile hunter-gatherer groups.

The site's age and complexity call into question established timelines that placed large-scale monumental architecture and organized religion only after the advent of agriculture. Instead, Göbekli Tepe suggests that social and spiritual development may have preceded, and potentially stimulated, the transition from foraging to farming.

Breaking the Conventional Timeline of Civilization

Challenging the Agricultural First Model

Traditional archeology framed the dawn of civilization around the Neolithic Revolution, a period when humans shifted from nomadic lifestyles to settled farming communities. This transition was believed to have directly enabled the development of more complex social structures, including monumental buildings and religious rituals. Göbekli Tepe disrupts this sequence by revealing a site requiring coordinated labor and social organization, created by people who had not yet fully embraced agriculture.

Radiocarbon dating places the site's construction around 9600 BCE, before the widespread domestication of plants and animals. This suggests that the need to build such elaborate ceremonial sites could have actually motivated humans to adopt agriculture to sustain increasingly settled and cooperative communities.

Rethinking Religious and Social Complexity

The discovery underscores religion’s potential as a catalyst for social complexity, independent from economic changes. The scale and craftsmanship at Göbekli Tepe indicate the presence of religious specialists or shamans and an organizational hierarchy sufficient to mobilize a large workforce for construction.

Significantly, the monumental pillars' depictions of animals—foxes, boars, snakes, and birds—may represent not just fauna but spiritual or mythological symbolism. This points to complex belief systems deeply embedded in prehistoric society, further disproving any notion that spirituality was a byproduct of settled life alone.

Architectural Marvels Predating Known Civilization

Göbekli Tepe’s architecture is astonishing for its time. The massive limestone pillars, some weighing up to 20 tons, were quarried and transported to the site without metal tools or the wheel—technological inventions that arose thousands of years later.

The arrangement of pillars into circular enclosures represents some of the earliest known examples of monumental architecture on Earth. The detailed relief carvings are artistic masterpieces that hint at a sophisticated cultural expression. It shows that early human groups prioritized community gathering and ritual above mere survival.

The site's eventual deliberate burial around 8000 BCE remains a mystery, possibly reflecting shifting societal values or environmental pressures.

Implications for Anthropological and Historical Studies

Göbekli Tepe has important repercussions for multiple scholarly disciplines:

-

Anthropology: It urges a reconsideration of social dynamics in the Upper Paleolithic, emphasizing cooperative behavior and shared belief systems as foundational to societal evolution.

-

Archaeology: The site challenges the criteria used to define 'civilization,' showing that complexity arose even in predominantly hunter-gatherer contexts.

-

History: It redefines the dawn of civilization as a more gradual, nonlinear process, with religious and social factors playing pivotal roles.

In the words of Klaus Schmidt, “Göbekli Tepe changes our view of our beginnings profoundly, showing that ritual and religion were key drivers in establishing the complex communities that eventually built civilization.”

Broader Cultural and Philosophical Impact

Göbekli Tepe invites us not only to rewrite historical narratives but also to reconsider the very nature of human progress. It intimates a past where spirituality and community were deeply intertwined and central to human identity across millennia.

Moreover, the site has inspired new cultural dialogues about our ancestors’ intellect and creativity. For instance, comparing Göbekli Tepe with other megalithic sites like Stonehenge highlights how early humans across regions shared a profound connection to their environments and cosmos.

Conclusion: A New Lens on Civilization

In sum, Göbekli Tepe is far more than an ancient ruin; it is a window into the early human mind and society. Its discovery challenges the foundational frameworks of civilization development by emphasizing the role of religious and social complexity before agriculture. As investigations continue, Göbekli Tepe promises to deepen our insight into humanity’s origins, reshaping not only historical scholarship but also our appreciation of prehistoric innovation and spirituality.

Understanding Göbekli Tepe encourages us to view civilization as an evolving tapestry woven from intertwined cultural, spiritual, and technological threads—an evolution still unfolding even today.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts