How Lucid Dreaming Reveals the Mysteries of Human Consciousness

11 min read Exploring how lucid dreaming unlocks new insights into human consciousness and cognitive processes. (0 Reviews)

How Lucid Dreaming Reveals the Mysteries of Human Consciousness

Introduction

Human consciousness remains one of the most enigmatic frontiers in science and philosophy. For centuries, scholars have pondered what it truly means to be aware, to perceive, and to experience subjective reality. Among the many phenomena linked closely to consciousness, lucid dreaming stands out as a fascinating gateway into the intricate workings of the human mind. Unlike typical dreams, lucid dreams occur when the dreamer becomes aware that they are dreaming and can sometimes even control the dream narrative. This unique state blurs the lines between wakefulness and sleep, offering profound insights into consciousness itself.

In this article, we dive deep into how lucid dreaming reveals the mysteries of human consciousness. From neurological research to psychological theories, we explore this extraordinary phenomenon, unpacking its implications on self-awareness, cognitive flexibility, and the nature of reality perception.

The Science Behind Lucid Dreaming

Defining Lucid Dreaming

Lucid dreaming is a state during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in which the dreamer is both conscious that they are dreaming and can often influence the dream environment. Psychologist Frederik van Eeden coined the term in 1913 after documenting his own experiences. However, scientific validation arrived decades later, when researchers demonstrated that lucid dreamers could communicate with the external world while still asleep using predetermined eye movement signals.

Neurological Correlates

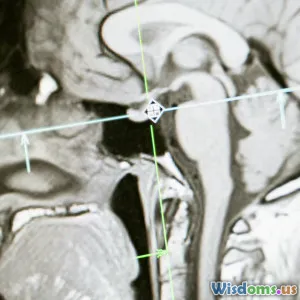

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalogram (EEG) studies have revealed that specific brain regions become activated during lucid dreams. For instance, the prefrontal cortex—responsible for executive functions such as decision-making, self-reflection, and metacognition—is typically less active during regular dreaming. In contrast, during lucid dreaming, this area shows increased activity, suggesting a heightened state of self-awareness.

A landmark study by Ursula Voss and colleagues (2013) used EEG data to show increased gamma wave activity (~40 Hz) in the frontal cortex during lucid dreams, directly linking this neurological pattern with conscious awareness within dreams. This discovery provided clear evidence that the brain operates uniquely under this hybrid state, combining characteristics of alertness and REM sleep.

Psychological Perspectives

From a psychological standpoint, lucid dreaming challenges traditional models that view dreams simply as unconscious signals or random neural firings. Instead, it suggests layers of consciousness that can be accessed voluntarily. Researchers have found that individuals skilled in lucid dreaming exhibit higher cognitive control and sensory centrality. Psychologist Paul Tholey proposed a model where lucid dreaming represents a state of meta-awareness—thinking about one’s own mental processes within a dream.

An intriguing report from the Lucidity Institute revealed that about 55% of people experience at least one lucid dream in their lifetime, and nearly a quarter encounter them regularly. This prevalence underscores lucid dreaming as a natural cognitive faculty, not merely an uncommon oddity.

Lucid Dreaming as a Mirror of Consciousness

Exploring Self-Awareness

Lucid dreaming essentially lets us watch consciousness in action—self-awareness nested in a dream. Philosophers and neuroscientists believe that this meta-awareness is the hallmark of consciousness itself. In lucid dreams, identifying “I am dreaming” parallels the “I think, therefore I am” reflection Descartes famously articulated. Here, the dreamer is simultaneously subject (experiencer) and observer (aware self), testing concepts of personal identity.

Lucid dreaming can invite an exploration of the narrative “self,” showing that identity and experience are malleable constructs. Dreamers often shift their perceived age, gender, or abilities fluidly. This plasticity hints at our brain’s inherent flexibility in modelling the self—an insight that could influence psychological therapy and understanding of dissociative disorders.

Overcoming Cognitive Boundaries

In waking life, reality constraints limit experience. Lucid dreams lift these barriers. Dreamers frequently accomplish incredible feats: flying, time travel, shape-shifting, or conjuring objects. Neuroscientist Stephen LaBerge, a pioneer in lucid dream research, documented a dreamer who managed a complex math problem in a lucid dream, evidencing sophisticated cognitive processing, even under sleeping conditions.

This demonstrates the potential to harness lucid dreams for problem-solving, creativity, and emotional resilience. It stretches our ideas about consciousness being a unitary state confined to waking life and shows that cognitive processes operate dynamically across states.

The Continuum of Consciousness

Lucid dreaming fits within the broader continuum of consciousness ranging from deep sleep to full alertness. It challenges sleep as a passive or unconscious process. Instead, it implies multiple interwoven layers of awareness operating simultaneously via complex neural orchestration.

Studies also explore parallels with mindfulness meditation, where practitioners cultivate meta-awareness of their thoughts and sensations. Both states—lucid dreaming and meditative mindfulness—highlight the brain’s capacity for observing without immediate reaction or confusion, enriching the neuroscience of consciousness training.

Real-World Implications and Applications

Therapeutic Potential

Lucid dreaming has gained traction as an innovative tool in psychotherapy. It offers patients a controlled environment to confront fears, process trauma, or rehearse coping mechanisms. For example, individuals with PTSD who suffer from recurrent nightmares can learn to become lucid during nightmares and consciously alter the outcomes—transforming terror into empowerment.

Similarly, lucid dreaming aids in improving emotional regulation by reducing anxiety and enhancing self-efficacy. Sleep research found that after training in lucid dreaming, participants reported decreased nightmare frequency and improved overall sleep quality.

Enhancing Creativity and Learning

Many artists, writers, and scientists attribute creative breakthroughs to insights gained from dreams, including lucid ones. Salvador Dalí and Mary Shelley famously acknowledged dreams as muse-like inspirations. Lucid dreaming can be deliberately practiced to stimulate creative problem-solving or artistic expression without external distractions.

Scientists have speculated that lucid dreaming might also improve skill acquisition. Dreams often replay motor functions, hinting that lucid dreaming could help athletes mentally rehearse movements or techniques during sleeping hours, potentially reinforcing neural pathways akin to wakeful practice.

Philosophical and Existential Insights

Lucid dreaming invites contemplation about reality’s nature—a question at the heart of philosophy. If one can be consciously aware inside a world that is purely internal, what does this imply about how consciousness constructs experience? This experiential paradox fuels debates in phenomenology and constructivist views of the mind.

Moreover, the boundaries blurred by lucid dreaming challenge materialist perspectives that strictly confine consciousness to brain activity, inspiring open inquiry across disciplines such as quantum cognition and transpersonal psychology.

Techniques to Induce Lucid Dreaming

For readers intrigued to explore lucid dreaming firsthand, several methods have proven effective:

- Reality Testing: Regularly questioning throughout the day whether one is dreaming, which can trigger lucid awareness while sleeping.

- Wake Back to Bed (WBTB): Awakening after 4-6 hours of sleep to stay awake briefly before returning to sleep increases REM duration and encourages lucidity.

- Mnemonic Induction of Lucid Dreams (MILD): Setting a clear intention before sleep to recognize dreaming.

- Wake-Initiated Lucid Dreams (WILD): Maintaining consciousness while transitioning from wakefulness to sleep, though this is more advanced.

Use of technologies such as light or sound cues synchronized with REM cycles is under experimental development to aid induction.

Conclusion

Lucid dreaming stands as a compelling phenomenon that not only captivates the imagination but also provides a profound window into the nature of human consciousness. By bridging waking cognition with dream states, it sheds light on self-awareness, cognitive flexibility, and the dynamic architecture of the mind.

Scientific advances reinforce the idea that consciousness is not a fixed state restricted to our waking hours but a fluid continuum that can be explored and harnessed. Beyond pure fascination, lucid dreaming offers promising pathways for mental health treatment, creativity enhancement, and philosophical inquiry.

Ultimately, embracing lucid dreaming expands our understanding of what it means to be conscious—awakening us to the vast mystery that is the human mind.

References and Further Reading

- Voss, U., Holzmann, R., Tuin, I., & Hobson, J.A. (2013). Lucid dreaming: A state of consciousness with features of both waking and non-lucid dreaming. Sleep, 36(9), 1317-1328.

- LaBerge, S. (1985). Lucid Dreaming. Ballantine Books.

- Tholey, P. (1988). Techniques for inducing and manipulating lucid dreams. Dreaming, 3(4), 259–268.

- Schredl, M. (2010). Lucid dreaming frequency and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(2), 241–245.

- Holzinger, B., Klösch, G., & Anderer, P. (2006). Studies with lucid dreaming as add-on therapy to gestalt therapy. International Journal of Dream Research, 20(2),161-172.

Explore your mind beyond reality — lucid dreaming may just be the key.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts