How the Ancient Sumerians Invented the First Writing System

15 min read Explore how the ancient Sumerians developed the world's first writing system and revolutionized communication. (0 Reviews)

How the Ancient Sumerians Invented the First Writing System

When we pick up a pen or type on a keyboard, it's easy to forget just how extraordinary the concept of writing truly is. The ability to record language transformed human civilization, paving the way for everything from law codes to love letters, from historical epics to casual shopping lists. While oral traditions stretched far into prehistory, it was the ancient Sumerians who carved out a novel means of communication over 5,000 years ago, giving birth to humanity’s very first writing system: cuneiform. This revolutionary development rippled through the ages, laying the foundation for written language across the world.

The World of Sumer: Fertile Ground for Innovation

The rise of writing did not happen in a vacuum. Around 3500 BCE, the Sumerian civilization blossomed in the fertile southern reaches of Mesopotamia—modern-day Iraq—where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers created bountiful land for agriculture. With the growth of abundant, staple crops such as barley and wheat, villages swelled into bustling city-states like Uruk, Ur, and Eridu.

Unlike earlier human settlements, Sumerian cities were complex, interconnected societies. Each city was an autonomous entity, often surrounded by massive walls and featuring ziggurats—step-pyramid temples housing powerful priesthoods. A growing population, sophisticated trade networks, burgeoning religious establishments, and centralized administrations created new challenges. The need for coherent, reliable record-keeping—for everything from taxes and trade to sacred offerings—was paramount.

The Invention of the Clay Tablet

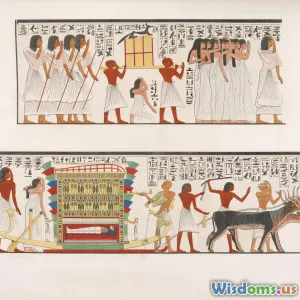

The earliest Sumerian written records were not penned but impressed onto damp pieces of clay. Around 3300 BCE, Sumerian scribes began recording information using small, flat tablets—a format durable enough to survive millennia.

Why clay? Unlike perishable materials such as papyrus or parchment, clay was cheap and plentiful along riverbanks. Sumerian scribes used a stylus made from reeds to impress signs into the pliable surface. Afterward, these tablets could be sun-dried or baked in a kiln, making them virtually indestructible. Thousands have survived to this day, offering contemporary scholars a rich window into this distant past.

Consider a typical clay tablet from ancient Uruk: it might list deliveries of grain, distributions of beer, or livestock ledgers. Each entry was vital for maintaining the city's logistical machine. Over time, the bureaucracy produced tablets for everything from contracts and wills to epic poetry, such as the legendary “Epic of Gilgamesh.”

From Tokens to Signs: Tracing the Path to Script

Cuneiform’s origins are rooted in an even older tradition of tangible counting. As far back as 8000 BCE, Mesopotamians managed resources using clay tokens, each representing commodities such as sheep, jars of oil, or quantities of grain. These tokens were enclosed in clay envelopes (bullae), which were marked with pictograms representing the contents—an early attempt at permanent accounting.

Sometimes, when numbers or types of goods grew complex, pictorial marks on the outside served as identifiers. Eventually, around 3500 BCE, scribes realized they could impress the symbols directly onto flat tablets, replacing the need for bullaenvelopes. This crucial transition moved Sumerians from three-dimensional tokens to two-dimensional graphical information, bridging the gap between mere record-keeping and the written word.

Archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat has exhaustively tracked these changes and points to the ‘proto-cuneiform’ as a crucial prelude to writing. These proto-cuneiform texts featured a variety of pictographs which gradually evolved to reflect abstract ideas as well as tangible goods—a pivotal leap in human communication.

Birth of Cuneiform: The First True Writing System

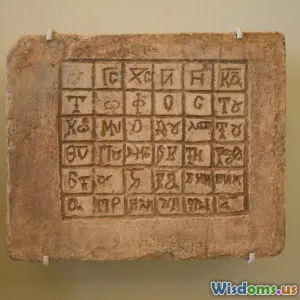

The word “cuneiform” comes from the Latin “cuneus,” meaning wedge. This describes the distinctive wedge-shaped impressions produced by the blunt reed stylus on clay.

At first, Sumerian writing was a system of pictograms. For instance, a simple picture of a fish denoted a food item, while a picture of barley stood for the crop itself. Over time, these pictograms were simplified and abstracted. Linear strokes began to ensure consistency in form, and signs rotated for ease of impression. Soon, around 3200 BCE, the Sumerians invented the wedge technique: by pressing the stylus at different angles and depths, scribes could create various shapes from a single tool.

A cuneiform sign, such as for the word “star” (DINGIR), gradually became more stylized and less literal until it was entirely abstract. This abstraction was critical. It allowed Sumerian writing to break free from the limitations of pure pictography—marking the pivot toward a true script that could record ideas, pronounceable names, actions, and pronunciations.

The breakthrough didn’t stop there. Sumerian scribes eventually developed hundreds of signs that could be combined to represent not only things but also sounds and syllables; the logographic (meaning-based) script began gaining syllabic and phonetic elements.

The Scribe: Professionalization and Curriculum

As writing became indispensable, a new profession arose: the scribe. Scribes quickly became central figures in Sumerian society, overseeing everything from tax administration and record archives to law and literature.

Scribal training was demanding. Most aspiring scribes were boys from elite families, enrolled in tablet houses known as “edubba” (literally, "tablet house"). Here, students learned to wield the stylus with precision on clay, copying set texts from vocabulary lists to grammatical exercises and, eventually, complex legal and literary compositions.

Curriculum at an edubba could take years to master. Texts uncovered near Nippur outline lists of Sumerian and Akkadian words, sign drills, proverbs, and model contracts. Such rigorous education ensured that scribes were not only functional accountants but also esteemed keepers of legal, mythological, and poetic tradition—the information technologists of their day.

Expanding Functions: Beyond Accounting

While cuneiform’s earliest use was record-keeping, its utility rapidly expanded. The world’s oldest known law code—preceding even the famous Code of Hammurabi—was etched by Sumerian rulers onto clay tablets. The so-called Code of Ur-Nammu, drafted around 2100 BCE, codified issues such as murder, theft, marriage, and slaves’ rights.

Cuneiform made possible the first-recorded fables, hymns, and mythologies. The Epic of Gilgamesh, composed in Sumerian and later translated into Akkadian, remains not only a literary masterwork but also an invaluable source for understanding ancient viewpoints on kingship, friendship, and mortality.

Temples utilized cuneiform for ritual inventories and offerings, while the state archives held extensive treaty records, diplomatic letters, property deeds, and administrative logs. Far beyond bean counting, cuneiform provided Sumerians a means to narrate their world and cement their legacy.

How Cuneiform Spurred Regional Change and Competition

The rise of Sumerian script resonated across Mesopotamia. As ambition and influence spread, so too did writing. Neighboring cultures adapted cuneiform to their own languages, notably the Akkadians—a Semitic people who rose to power in the northern region. With only minor modifications, Akkadian scribes adopted the script and tailored it to represent their own spoken tongue.

This adaptability was both a testament to the cuneiform system’s flexibility and a catalyst for further cultural exchange. Soon, Elamites, Hittites, Assyrians, and Babylonians each recalibrated the script to fit their linguistic needs, incorporating thousands of alternate signs and pronunciation guides. Writing thus became a diplomatic and scholarly lingua franca in the ancient Near East—impossible to forge empires or peace without scribes in tow.

Challenges and Limitations of the Sumerian Writing System

While ground-breaking, cuneiform was not without flaws. With hundreds of distinct signs to memorize—some with multiple uses, depending on context—learning to read and write was a rare, specialized skill. Ambiguity persisted, especially as pictograms morphed into abstract characters that sometimes represented both words and sounds. There was no standardized spelling, and the way a sign was drawn could differ across city-states or historical eras.

Preservation was uneven: many tablets, especially those dried in the sun rather than kiln-fired, crumbled over time. Additionally, the sheer laboriousness of inscribing lengthy texts on clay limited writing’s scope. Even so, the enduring cuneiform tradition outlasted the Sumerians themselves, continuing (with mutations) into the first century CE—almost 3,000 years.

Methodologies for Decoding Ancient Sumerian Writings

Modern researchers have invested painstaking effort in deciphering cuneiform. The codebreaker moment came in the 19th century, when explorers unearthed thousands of tablets from sites like Nineveh and Babylon—often fragmentary, sometimes wholly intact.

By comparing Sumerian cuneiform with Akkadian equivalents (and, later, Old Persian trilingual inscriptions like the Behistun Inscription), specialists established sign lists and sound values. Today, digital imaging technology and crowdsourced projects such as the CDLI (Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative) continue to bring new transcriptions and translations to light.

This work has upended previous assumptions about the ancient world, allowing us to reconstruct not just who the Sumerians were, but how their conceptualizations—of markets, the cosmos, and their places in both—evolved.

Lasting Impact: Why Sumerian Writing Still Matters

Few inventions have left so permanent a mark on civilization as the written word. The Sumerians’ cuneiform system gave birth to the intertwined concepts of historical record, administrative accountability, and narrative storytelling—all via intentional symbols captured on clay. Nearly every major ancient power in Mesopotamia drew on this tradition, adapting and evolving the approach to suit new times and languages.

Some Sumerian cuneiform signs have echoed through history—for instance, the sign for “god,” DINGIR, survived into later Akkadian as both a sound and a determinative symbol. Even today’s forms of record-keeping, storytelling, law, accounting, and scholarship are a direct inheritance of that first clay tablet placed beneath the reed stylus.

So, whenever you pen a note or send an email, remember: you’re participating in a tradition begun five millennia ago, by enterprising scribes in the sweltering cities of ancient Sumer. Their bold leap from symbol to script cemented the written word as a pillar of humanity’s cultural and intellectual journey.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts