Could the Indus Script Be an Ancient Tech Code

15 min read Exploring whether the Indus script represents an early form of technological coding. (0 Reviews)

Could the Indus Script Be an Ancient Tech Code?

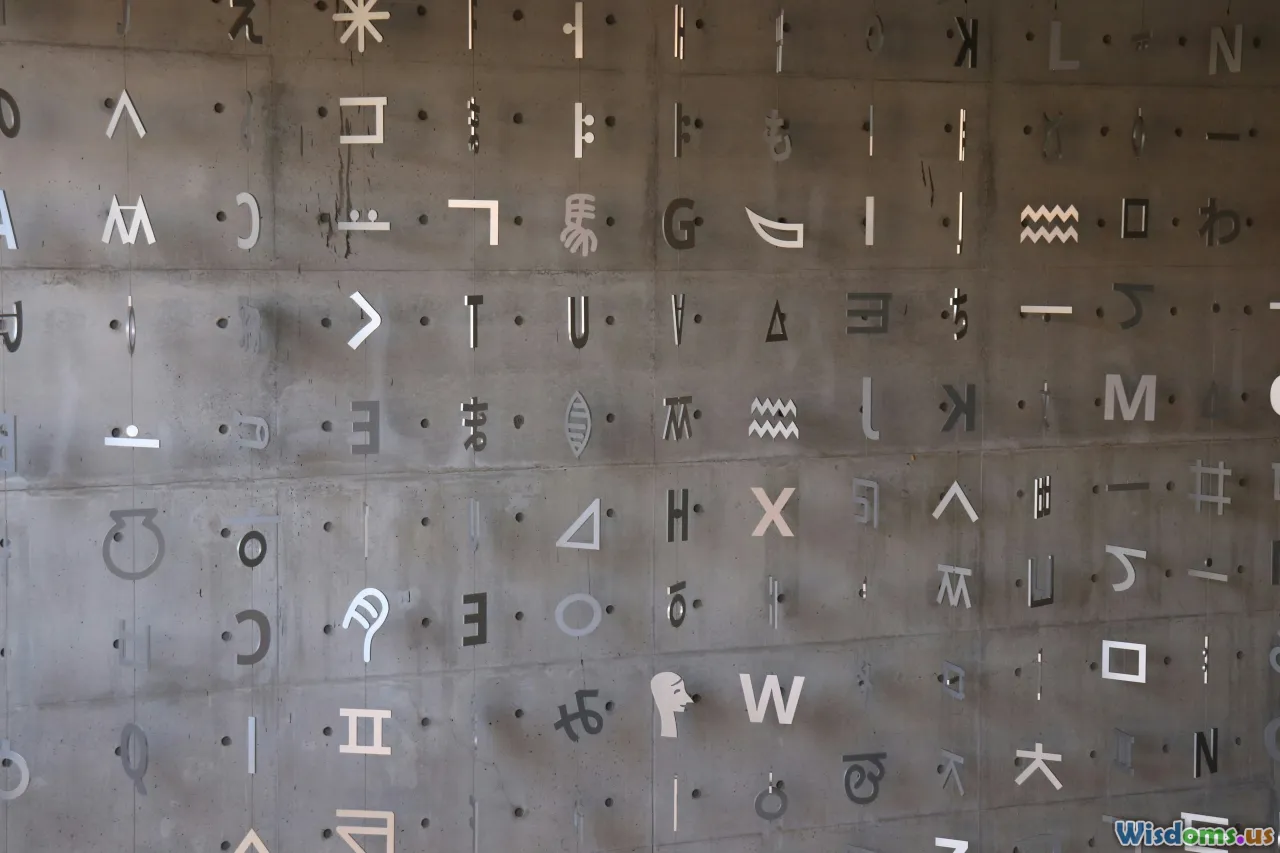

When people imagine the roots of technology, images of computers, glinting circuitry, and smartphones often come to mind. Yet, history is a vast tapestry, and sometimes its earliest, most tantalizing threads are right under our noses. One enduring mystery sits at the crossroads of script, symbolism, and ancient knowledge—the enigmatic Indus script. Over 150 years since its discovery, no archaeologist or linguist has deciphered it. But an intriguing question lingers: could the Indus script, carved into steatite seals and potsherds millennia ago, represent not just proto-writing but an actual code—a kind of technical notation or information system developed long before those of Mesopotamia or China? Let’s take a journey through the evidence, theories, and modern techniques unraveling this possibility.

The Puzzle of the Indus Script

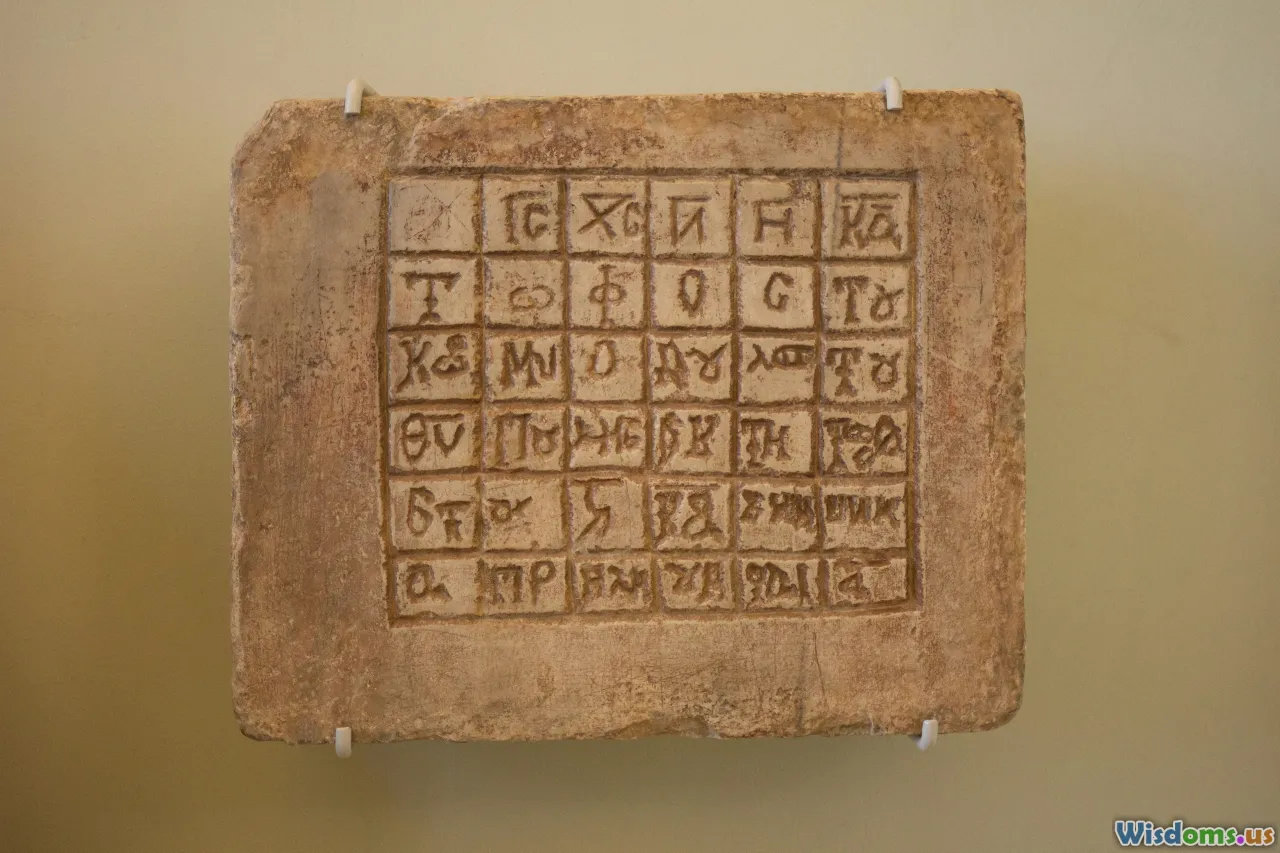

Discovered among the ruins of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro at the turn of the 20th century, the Indus script is a system of shapes and abstract signs, sometimes accompanied by curious animal motifs. Archaeologists date these inscriptions between 2600 and 1900 BCE, from one of the world’s earliest urban centers: the Indus Valley Civilization. Over 6,000 examples are known, mostly brief—just a few marks long.

Efforts to crack this code have energized and frustrated generations of scholars. Someone encountering these succinct lineups—like a fish, a trident, or a row of vertical dashes—might dismiss them as mere decorations, but meticulous studies say otherwise. Repetition and careful etching hint at something systematic—a grammar, be it language, cataloguing, or something entirely different.

"The brevity and standardized formatting of the inscriptions suggest they were meant to convey highly specific information."

Main challenges include:

- A lack of bilingual inscriptions (like the Rosetta Stone for Egyptian)

- Frequent use of brief texts, hampering comparisons

- Unknown associated language or languages

Yet, the perplexity only adds to the romance of what could be the world's oldest undeciphered writing system.

Is It Writing? Or a Tech Code?

Traditional theories classified the Indus script as logographic (one symbol = one word/concept) or logo-syllabic (symbols combine phonetic and semantic roles), akin to Sumerian cuneiform or Egyptian hieroglyphs. If so, the brief scripts would seem anomalously short. Lately, however, a provocative theory has gained attention: what if these symbols weren’t recording speech? What if they encoded technical or administrative information, such as warehouse numbers, weights, production records, or industrial instructions?

This idea isn’t fanciful. Consider these historical analogues:

- Proto-Elamite tablets (3100–2900 BCE) used numeric and pictorial symbols, without clear grammar, to log economic transactions.

- Knossos Linear A tablets, thought to record commodities in Minoan storage rooms (1700–1400 BCE), remain mostly undeciphered but evidently used for non-literary admin.

Scholars like Rajesh Rao have argued for comparing Indus signs to structured data:

"Might the Indus script be comparable to ‘tags’ or encrypted codes used as tokens or identifiers almost like barcodes?"

If the Indus civilization was tracking trade, taxes, or production quantities—vital for a city-centered economy—it’s plausible they devised a visual code reflecting quantities, categories, and authority.

Evidence for a Systematic, Possibly Technical, Notation

Statistical and computational analyses over recent decades have trickled out clues. In 2009, scientists led by Rao applied entropy measures—familiar to computer scientists—from information theory to the Indus script. They found the arrangements of signs were closer in predictability and structured pattern to true written languages than to collections of random symbols.

Some concrete technical findings include:

- Directional consistency: Inscriptions show standardized beginnings and endings, like designated start and stop signs in coding.

- Cluster patterns: Frequently corollary groups of symbols—possibly denoting a name/class/purpose + numeric value or operator, as seen in early ledgers.

- Distribution regularity: Certain symbols always appear in specific positions, comparable to headers or signature elements in data records or codes.

Take the sequence: ‘fish’ symbol followed by numerals—recurring frequently, suggesting the first specified a commodity (perhaps fish, oil, or something symbolic) and the second a value. Similar patterns turned up on Mesopotamian ration tokens and tally sticks.

Decoding Attempts: Eureka or Dead Ends?

No Indus script breakthrough has shaken the world like Champollion’s decipherment of hieroglyphics. Nevertheless, the process of code-breaking can look surprisingly modern:

Classic approaches:

- Structural linguistics: Attempting (without success) to pair signs with archaic Dravidian, Sanskrit, or other language roots

- Bilingual hunt: Scouring for an 'Indus Rosetta Stone' among Mesopotamian exports, without success so far

Recent digital efforts:

- In 2021, IBM researcher Uli Selig studied the mathematical structure of sign sequences, finding they strongly resembled computational forms—more regular than mere art, suggesting rules like you’d find in a code machine.

- The Turing Indus project applies Markov models (statistical chain predictions), leveraging thousands of AI simulations to suggest which signs must follow or precede others, mimicking how digital protocols require order and checksums.

Some visionaries call this era the dawn of digital archaeolinguistics, speculating that Indus signs might preserve a mnemonic, symbolic language—akin to a ‘visual programming language’ predating known writing, at least as code.

The Function of Indus Seals: Tech in Commerce and Administration

Physical context gives us vital hints. The majority of script samples are on steatite seals—hand-sized squares engraved with text and sometimes animal icons. These weren’t decorative tokens. Archaeologists have found them near granaries, workshops, warehouses, and ports.

Possible tech-like functions:

- Authentication: Merchants could stamp goods as certified origin, like modern QR codes, or perhaps as permission marks used in trade—preventing fraud and structuring taxation

- Commodity Tracking: Seal impressions on bales and pottery may have labeled item type, owner, batch, or a destination—a prehistoric logistics system

- Access Control: Certain unique or complex symbols reserved for authorities—comparable to cryptographic ‘keys’ or passcodes

Contemporary analogues amplify these comparisons:

- In China, tally sticks and notched bones recorded inventories for census and taxes.

- In Mesopotamia, cylinder seals not only marked property but authenticated records for industrial and legal purposes.

It’s not far-fetched to think of Indus stamps as an information technology—perhaps primitive, but critical, supporting one of the world’s earliest big-data economies.

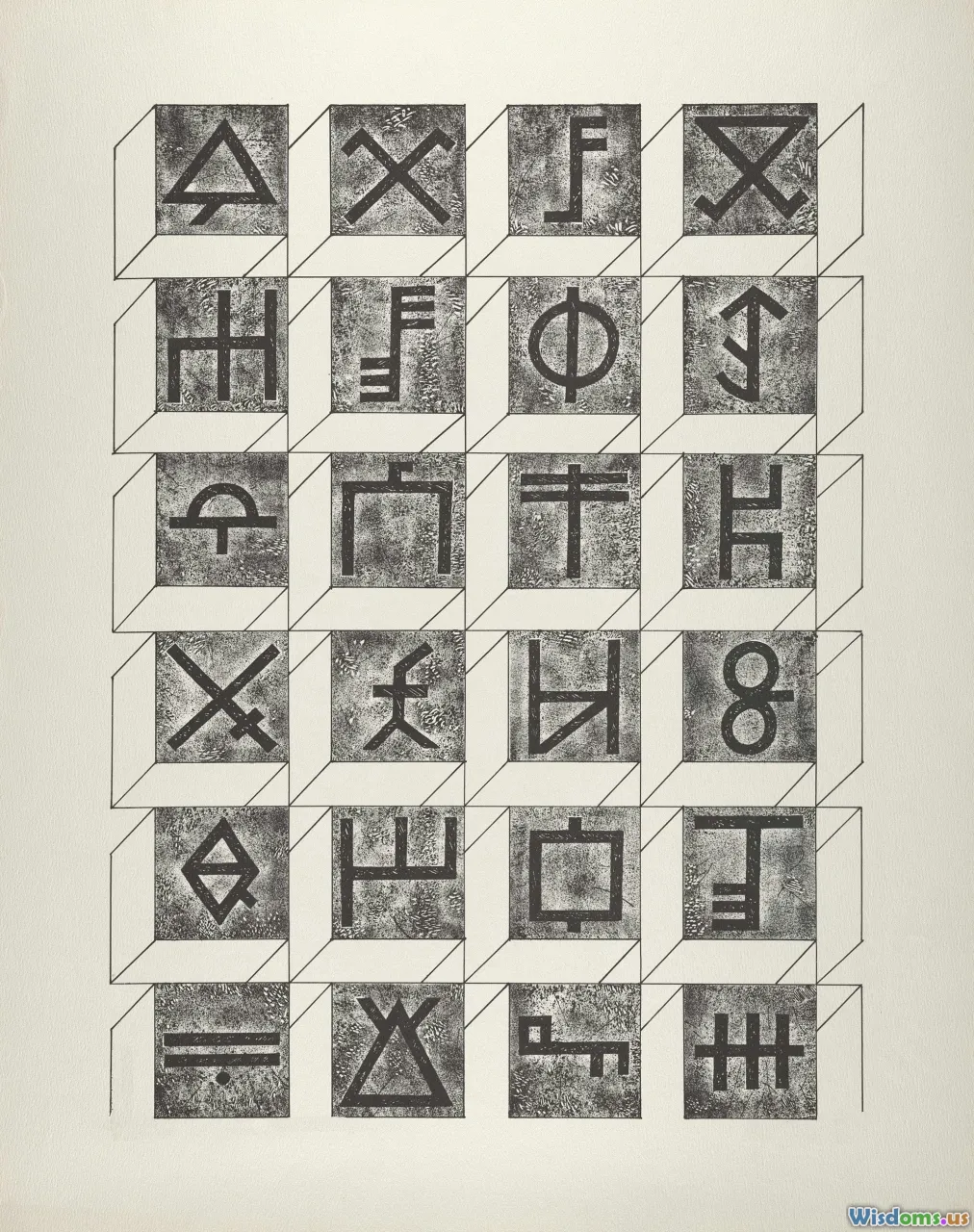

Symbolism, Semantics, and the Art of Machine Language

Stepping away from pure numbers, some researchers have highlighted the Indus script’s pervasive use of symbolic motifs—particularly animals (unicorns, bulls, elephants), plants, geometric shapes (dots, lines, tridents), or tools. The density and recurrence beg the question: are they literal, or serving as abstracted category markers—like metadata in modern databases?

For example:

- The recurring ‘unicorn’ symbol is present on over 60% of seals, always at a prominent position: Could this be a logo, a fiscal authority’s symbol, or a hallmark representing an entire city?

- Peculiar ‘forked posts’ or ‘ranged dots’ could serve as branching/operation modifiers, paralleling Boolean logic—yes/no, add/subtract.

Some anthropologists even speculate that the script encoded workflow rules as much as language: like ancient flowcharts, in which images and shapes define conditions and outcomes for trade, taxes, and permissions. In this way, Indus script may straddle the border between writing, programming, and symbolic logic—uniquely suited to oral-administered, information-heavy economies.

Comparative Glance: Indus Code & Modern Data Systems

The leap from steatite seals to silicon chips might seem vast. Yet, in format and function, proto-scripts like the Indus arguably share DNA with today’s information coding standards. Let’s break down some parallels:

| Indus Script Practice | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Pictorial, compressed markers | Emojis, pictograms |

| Rule-based sign order | Structured data formats (XML, JSON) |

| Contextual-role symbols | Metadata and headers |

| Repetitive, short text for access | Passwords, badge IDs, barcodes |

| Seals as access/authentication | Digital signatures, NFC chips |

By today’s standards, these are all flavors of encoding—select units of information embedded in patterned marks to guarantee the function and reliability of records, trade, and control.

Digital historians like Tom Griffiths observe that what sets apart a “code” from writing is its purposeful limitation—codes dismiss literary verbosity for compressed, function-first data. In this sense, the Indus script may well be an ancestor not to cursive calligraphy, but to the world’s very first login screens, ID checks, and version controls.

Lessons for Digital Archaeology—and the Limits of Speculation

As alluring as these comparisons are, historians urge caution. We must never underestimate the cognitive divide: modern programming, while built on ancient roots, reflects centuries of abstraction and systemic thinking unknown to ancient artisans.

Nevertheless, pursuing the Indus script as a technical code has spurred actionable breakthroughs in research methodology:

- Big Data Archaeology: Hundreds of inscriptions are now catalogued, their sign frequencies and clusters mapped with machine-learning tools like TensorFlow and neural embeddings.

- Collaborative decipherment: Scholars worldwide use open datasets to crowdsource pattern recognition, much like open-source software development.

- New field trials: Experimental archaeology is attempting to replicate seal-making and inscription, looking for statistical clues in how symbols are engraved, repeated, or organized.

Perhaps the most critical lesson is that technological thinking—seeing the Indus script as a proto-digital code rather than a mere archaic script—helps us picture ancient societies not as primitive, but as sophisticated managers of complex systems, already dabbling (in their own way) with information technology long before Turing or the age of the algorithm.

Curiosity abounds, and so too does the enduring thrill of an undeciphered message, whispering across the span of time, from the kiln-fired dens of Mohenjo-daro to the clouds of today’s digital world. If the Indus script truly is a lost tech code, its ultimate decryption may one day not only rewrite history, but redefine what we mean by coding itself.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Indus Valley Civilization

Popular Posts