Lessons from Göbekli Tepe Are We Rethinking Prehistory

9 min read Explore how Göbekli Tepe reshapes our understanding of prehistoric civilization and challenges long-held archaeological beliefs. (0 Reviews)

Lessons from Göbekli Tepe: Are We Rethinking Prehistory?

Human history is a vast, unfolding tapestry, often stitched with accepted timelines and linear narratives. But every so often, an archaeological discovery emerges to upend these narratives — and Göbekli Tepe stands as one of the most stunning examples. Hidden away in the southeastern Anatolian region of Turkey, Göbekli Tepe is a sanctuary of monumental stone pillars dating back over 11,000 years, radically predating Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids. This ancient site is not only extraordinary for its age but raises profound questions about how and when human civilization began.

In this article, we'll investigate how Göbekli Tepe challenges previously held assumptions, what it teaches us about prehistoric humans, and why it compels a reassessment of the origins of organized society.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

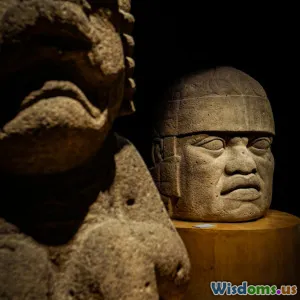

Göbekli Tepe was first uncovered in the 1960s but only gained extensive attention when German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt began excavations in the 1990s. The sheer scale and symbolic complexity of the site stunned experts. Unlike other early settlements that grew out of subsistence farming and simple huts, Göbekli Tepe's pillars are intricately carved with animals, abstract symbols, and motifs — craftsmanship that suggests a sophisticated hunter-gatherer society.

Dating reveals the site was built around 9600 BCE, during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period. At this juncture, the dominant hypothesis was that complex social structures and monument-building arose only after communities mastered agriculture. But Göbekli Tepe was clearly erected before the widespread adoption of farming, overturning the idea that settled agriculture precedes religious and social complexity.

Rethinking Timeline: Hunter-Gatherers as Builders

Traditional archaeology has framed the hunter-gatherer phase as a simple, egalitarian era marked by small, mobile groups with limited social hierarchy. Agriculture, around 9500 BCE, was believed to herald a pivotal transition to sedentary communities that enabled labor specialization and monumental construction.

Göbekli Tepe pushes us to ask: How did mobile hunters coordinate massive construction projects? Select pillars reach up to 5.5 meters and weigh 10-20 tons, requiring organized labor, engineering knowledge, and social coordination previously unimagined. This indicates early humans may have formed complex social networks for religious or ritualistic purposes before they developed agriculture.

Moreover, some researchers argue that the desire to build and maintain these sites may have been an impetus toward the eventual cultivation of plants — turning the standard causality on its head.

Symbolism and Spirituality in Prehistory

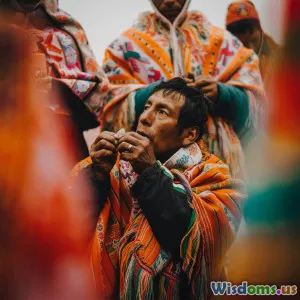

The elaborate animal carvings — lions, scorpions, boars, snakes — hint at deep-seated symbolic or spiritual beliefs. Some scholars interpret these as totems or cosmic allegories, suggesting early humans engaged in ritualistic behavior addressing life, death, and their environment.

This challenges the notion that spirituality emerged only with agricultural surplus enabling leisure time for contemplation. Instead, spiritual life may have been a strong galvanizing force even among hunter-gatherers, influencing their social cohesion and identity.

Anthropologist Ian Hodder notes in his analysis, "Göbekli Tepe reshapes how we think about ideological complexity — it is as ancient as the transition to farming but is separable from economic factors."

Environmental and Social Context

Situated near a rich ecological zone by Mesopotamia's Fertile Crescent, Göbekli Tepe offers insights into human-environment interaction at the end of the last Ice Age. The site’s appearance coincides with climatic shifts that made the region more hospitable, potentially supporting larger groups and more stationary lifestyles.

Nevertheless, the site's builders apparently did not settle down permanently here; Göbekli Tepe appears to have been a ceremonial or pilgrimage center rather than a living village, indicating an early complexity where different groups possibly congregated periodically.

This social dynamism challenges the simplistic hunter-gatherer/population-centric models and suggests ritual landscapes played a critical role in prehistoric human societies.

Broader Archaeological Impacts

Göbekli Tepe has paved the way for a scholarly debate that questions long-standing prehistoric models. Several implications stand out:

- Monumentality Before Sedentarism: It complicates linear models where settlements and agriculture naturally precede temple building.

- Origins of Religion: It supports the idea that religion might have been one of the original catalysts for complex society.

- Social Organization: It evidences advanced cooperation among hunter-gatherers, implying social structures were already sophisticated.

- Regional Influence: Signs of similar but smaller sites nearby might indicate a networked culture rather than isolated 'cult centers.'

Leading figures in archaeology are adapting textbooks and theories to accommodate this newer understanding, influencing how we identify and interpret other ancient sites.

Lessons for Today’s Archaeological Approach

Göbekli Tepe also embodies a meta-lesson in humility for archaeology and history. It serves as a reminder that human origins are more intricate than linear progressions suggest. Sites like this urge a more open-minded and interdisciplinary methodology, integrating:

- Advanced Dating Techniques: Radiocarbon and stratigraphic precision are vital.

- Collaborations Across Fields: Insights from anthropology, climatology, and sociology enrich interpretations.

- Reassessment of Other Sites: Earlier work must be revisited with fresh perspectives.

It inspires archaeologists and historians to expect the unexpected and be wary of oversimplified narratives.

Conclusion: A Paradigm Shift Rooted in Stones

Göbekli Tepe, with its grand pillars and enigmatic artistry, is more than an archaeological site — it is a narrative disruptor. It overturns simplistic notions that religion, monumental architecture, and social complexity came only after farming. Instead, it positions spirituality, cooperation, and social hierarchy at the heart of hunter-gatherer societies.

This revelation not only amplifies the mystery of human prehistory but reframes it with new urgency. It prompts us to look at ancient human endeavors with fresh eyes and respect the deep roots of creativity and community.

As new excavations continue and technology advances, Göbekli Tepe promises to remain a cornerstone of prehistoric knowledge — reminding us that history is a dynamic story, ever unfolding beneath our feet.

References:

- Schmidt, K. (2010). Göbekli Tepe – the Stone Age Sanctuaries: New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Documenta Praehistorica.

- Hodder, I. (2017). Religion in the Emergence of Civilization: Göbekli Tepe and the Ritual Landscape of the Neolithic Near East.Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

- Dietrich, O., & Heun, M. (2012). "Göbekli Tepe – The Birth of Religion?" Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

For those intrigued by the intersections of human history and mystery, Göbekli Tepe stands as a timeless beckon — challenging us to rethink, rediscover, and relish the complexity of our ancestors.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts