The Connection Between Language and Civilization

8 min read Explore how language shaped ancient civilizations and unlocked archaeological mysteries across history. (0 Reviews)

The Connection Between Language and Civilization

Language is often called the backbone of civilization, a beacon guiding societies from mere survival to sophisticated cultural entities. But how deeply intertwined are language and civilization? When we examine ancient civilizations and the archaeological mysteries that persist, the answer becomes undeniably profound.

Introduction: Unlocking the Past Through Words

Imagine finding a clay tablet inscribed with intricate symbols or a wall etched with pictographs. Suddenly, an archaeological find shifts from being a silent relic to a narrative brimming with historical insights — but only if the language can be understood.

Language isn’t just a tool for communication; it serves as a vessel carrying culture, identity, governance, and history. Ancient languages open doors to understanding how early humans interacted, governed territories, worshipped, and legacies they left behind.

This article will explore how language and civilization have influenced each other throughout history, focusing on:

- The foundational role of language in forming complex societies

- The development and significance of ancient writing systems

- How deciphering ancient scripts unravels archaeological mysteries

- The influence of linguistic evolution on cultural preservation

Language as the Infrastructure of Civilization

At its core, civilization requires coordination — between individuals and groups, across disciplines and regions. Language provides the infrastructure for this coordination.

Communication and Social Complexity

Early hunter-gatherer communities were bound by basic communication. But as societies shifted toward agriculture and trade around 10,000 BCE, communication demanded more sophistication. Language enabled:

- Regulation of social norms: Laws and customs could be transmitted consistently.

- Economic exchange: Bartering and trade required shared understanding.

- Political organization: Hierarchies and governance structures depended on messaging.

Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber observed that without language, "a society cannot transcend immediate experience, nor can it build institutions that outlast the individual." This implies that language is a fundamental enabler of cultural memory and social progress.

Oral Traditions to Written Records

The earliest languages were purely oral, relying on memory and performance. However, this created barriers for expansive record-keeping and administration.

With civilization’s growth — notably in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley — recorded languages emerged, ushering in writing systems. This transition was pivotal as writing externalized memory, allowing:

- Preservation of laws and treaties

- Documentation of religious beliefs

- Recording of economic transactions

Ancient Writing Systems: Foundations of Cultural Identity

The invention of writing allowed civilizations to codify their ways of life and endure beyond oral tradition’s limitations.

Cuneiform: Mesopotamia’s Legacy

Dating back to around 3200 BCE, Mesopotamians developed cuneiform—a script inscribed on clay tablets. Initially created to tally goods and manage agricultural resources, cuneiform evolved to document myths, laws (like the Code of Hammurabi), and astronomical observations.

This script reveals Mesopotamia’s social hierarchies and technological advancements, illustrating how language powered early civilization.

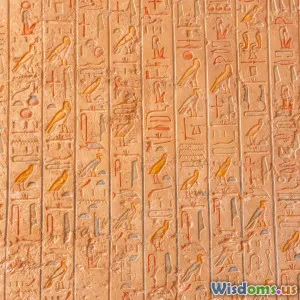

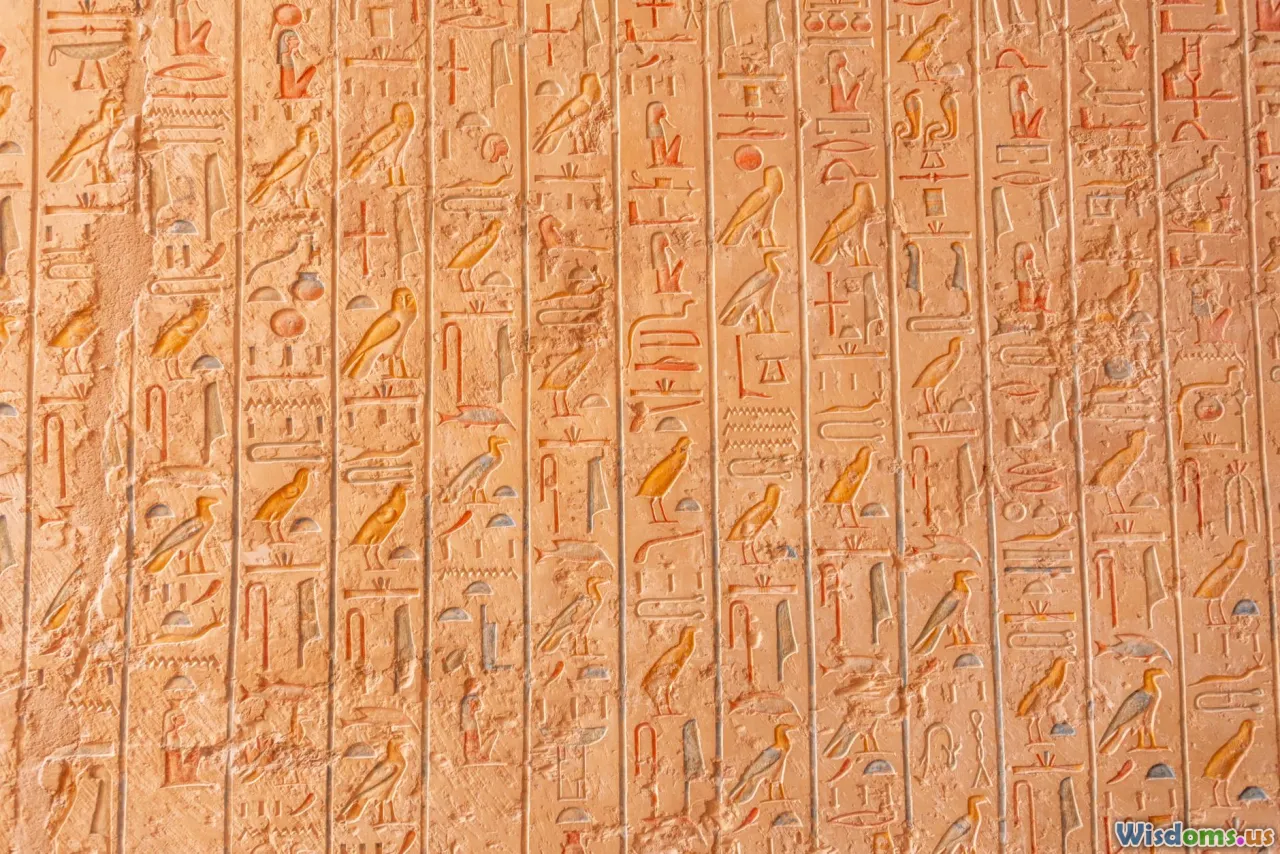

Hieroglyphs: Egypt’s Sacred Writing

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs date back to roughly 3100 BCE. Beyond administration, hieroglyphs carried profound religious and symbolic importance, decorating temples and tombs. They captured the Egyptian worldview and provided clues to their elaborate belief systems.

The meticulous craftsmanship behind hieroglyphic inscriptions highlights language's role not just as communication but as art and cultural identity.

The Indus Script: An Unsolved Puzzle

One of archaeology’s great mysteries is the Indus script from the Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2600–1900 BCE). Despite extensive discoveries of inscribed seals, this language remains undeciphered, limiting understanding of one of the world’s earliest urban societies.

The inability to read this script puts a barrier on fully grasping the civilization’s political structure, economy, and society. It exemplifies just how critical language decrypting is to piecing together our history.

Deciphering Ancient Scripts: Keys to Archaeological Mysteries

The study of lost and ancient languages has led to some of the most thrilling breakthroughs in archaeology.

The Rosetta Stone and Egyptian Decoding

Discovered in 1799, the Rosetta Stone featured the same text in Greek, Demotic, and Egyptian hieroglyphs. Jean-François Champollion’s successful decipherment in the 1820s unlocked nearly 4,000 years of Egyptian history previously inaccessible.

This achievement not only illustrated the synergy between languages but also exemplified how understanding linguistic codes is indispensable in interpreting civilization's narratives.

Linear B and Mycenaean Greece

In the 1950s, Michael Ventris decoded Linear B script, revealing it was an early form of Greek. This opened up insights into Bronze Age Greek administrative systems, religious practices, and societal organization, transforming understandings of European prehistory.

Challenges of Unreadable Scripts

Conversely, scripts like the Rongorongo of Easter Island or the Proto-Elamite scripts remain undeciphered. Their true meanings—be it myth, governance, or social history—continue to elude scholars, symbolizing linguistic puzzles awaiting future breakthroughs.

Language Evolution and Cultural Preservation

Languages themselves evolve, mirroring the shifts in civilizations. The disappearance of tongues often heralds cultural loss and fragmentation.

The Death and Revival of Languages

For example, Latin’s transformation into the Romance languages demonstrated language’s adaptation but also cultural shifts across Europe. Meanwhile, efforts to revive languages like Hebrew in the 20th century illustrate how language revitalization can reconstruct and solidify national identity.

Linguistic Diversity and Anthropology

Today, over 7,000 languages flourish, preserving unique worldviews and histories. However, UNESCO warns that a language dies every two weeks, risking cultural erasure that impacts our cumulative human knowledge.

Conclusion: Language Is Civilization’s Soul

Language is neither a mere practical tool nor a simple relic; it is the essence of civilization enabling knowledge transfer, social organization, and cultural expression. The enduring legacy of ancient languages lies in their irreplaceable role revealing how human societies evolved, thrived, and sometimes vanished.

Archaeological discoveries tied to deciphering languages have reshaped history and continue to inspire exploration. As we strive to understand humanity’s past, protecting linguistic diversity and investing in language research preserve the keys to unravelling civilization’s grand mysteries.

In crossing the bridge between language and civilization, humanity gains not just historical perspective but also insight into the shared threads that bind us as a species.

Exploring language through the lens of ancient civilizations reveals the profound ways in which speech and script have forged human existence and identity across millennia.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Historical Linguistics

Popular Posts