Why Do We Forget Most of Our Dreams A Brain Science Perspective

8 min read Explore brain science insights on why we forget most dreams and how memory impacts our dream recall. (0 Reviews)

Why Do We Forget Most of Our Dreams? A Brain Science Perspective

Dreams have fascinated humans for millennia—enigmatic fragments that flicker through our minds, often fading as quickly as they appear. Despite the countless hours we spend asleep, most of us struggle to remember our dreams when we wake. But why does this happen? What does brain science reveal about this phenomenon? In this article, we dive deep into the neuroscience of dreaming and memory to uncover why most dreams evade our recall.

The Elusive Nature of Dream Recall

Before diving into brain science, it’s worth highlighting just how common forgetting dreams really is. Research shows that around 95% of all dreams are quickly forgotten, often within minutes after waking. Psychologist Calvin Hall found that dream recall occurs most often when awakening directly from REM sleep but diminishes sharply if several minutes pass.

Imagine waking up and having just experienced a vivid adventure in your mind—a meeting with lost loved ones or flying through a surreal landscape. Within moments, that memory blurs and often disappears altogether.

Brain Structures Involved in Dreaming and Memory

Understanding why dreams vanish requires examining two main brain components: those generating dreams and those responsible for memory encoding.

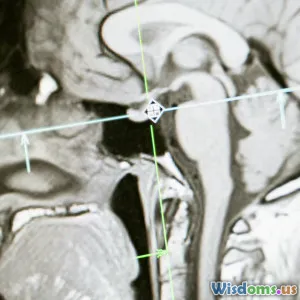

The Role of the Hippocampus

The hippocampus, nestled deep within the temporal lobe, is integral to forming and stabilizing new memories—especially episodic memories which encode experiences and events. However, during REM sleep (the phase when most vivid dreaming occurs), the activation of the hippocampus is surprisingly suppressed.

A study by Maquet et al. (1996) demonstrated reduced hippocampal activity during REM sleep, suggesting the brain may not efficiently transfer dream memories into long-term storage at this time. The hippocampus is busy processing waking memories rather than preserving dream content.

Prefrontal Cortex’s Activity Suppression

The prefrontal cortex—a region that governs rational thought, organization, and working memory—is known to be less active during REM sleep. This deactivation partially explains why dreams might be illogical or strange. Crucially, this same suppression means the brain is not engaging in typical memory encoding or self-reflective processes that happen while awake.

Without the prefrontal cortex’s support, the transient and emotionally charged content of dreams is less likely to embed itself firmly in memory.

Neurotransmitters and Memory Formation

Neurotransmitters like norepinephrine (linked with attention and memory consolidation) drop to extremely low levels during REM sleep. This lack of norepinephrine further reduces the brain's ability to form lasting memories during dreaming.

The Nature of Dream Memories

Even if parts of dreams are momentarily stored, their nature may prevent easy recall:

-

Fragmented Content: Dreams often lack coherent narrative structures, making them more difficult for the brain’s memory systems to encode fully.

-

Emotional Overload: Dreams are highly emotional and surreal, sometimes overwhelming normal memory pathways with intense sensory data.

-

State-Dependent Memory: Dreams occur in a sleeping state where neural activity patterns differ massively from waking. Memories formed in one brain state often don’t transfer easily to another.

Put simply, the brain might recognize dreams as fleeting, internally created images rather than important external experiences.

Experimental Evidence Behind Dream Forgetting

Neuroscientists have conducted experiments manipulating sleep stages and memory to test dream recall.

One famous experiment by Stickgold, Malia, Maguire, Roddenberry, and O’Connor (2000) found participants who woke spontaneously during REM reported more dreams. Conversely, waking participants during non-REM phases led to fewer and less vivid reports.

Furthermore, damage to the hippocampus in patients suffering amnesia drastically reduces dream recall, reinforcing its pivotal memory role.

Is Forgetting Dreams Ever Beneficial?

Forgetting dreams isn’t merely a brain shortfall—it might be adaptive. Dreams often evolve as the brain processes emotions and experiences, integrating them subconsciously. If every dream was preserved and vividly recalled, it could overwhelm waking cognition or blur lines between reality and imagination.

Moreover, the brain’s pruning of dream content may reflect a survival advantage—focusing limited neural resources on memories essential for conscious life rather than ephemeral nocturnal fantasies.

Tips Backed by Science to Improve Dream Recall

Despite natural forgetting, some techniques enhance our ability to remember dreams:

-

Keep a Dream Journal: Writing down dreams immediately upon waking capitalizes on the brief window before they fade.

-

Wake During REM: Using alarms or natural rhythms to awaken during or right after REM stages can improve recall. Sleep tracking apps can help monitor these phases.

-

Enhance Sleep Hygiene: More restful, longer sleep cycles allow for multiple REM phases & better memory processing overall.

-

Mindfulness and Intention: Simply telling yourself before sleep to remember dreams increases awareness and retrieval, demonstrating the power of priming.

Conclusion: The Brain’s Dream Forgetting Mystery

Our brain’s remarkable capacity to dream contrasts sharply with the fleeting recall of those dreams when awake. Neuroscience reveals that key memory centers like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex reduce activity during REM sleep, hampering the encoding of dream experiences into long-term memory.

Combined with the bizarre, emotional, and fragmented nature of dreams plus low levels of essential neurotransmitters, it’s no surprise that most dreams slip away unnoticed.

Yet this forgetfulness may be necessary, allowing our brains to focus on relevant waking memories and maintain mental clarity.

For those fascinated by dreams, however, employing strategies like journaling and intentional recalling can open a window into the inner workings of this most mysterious aspect of human cognition.

Dream on—and try to remember.

References:

- Maquet, P., et al. (1996). Functional neuroanatomy of human rapid-eye-movement sleep and dreaming. Nature.

- Stickgold, R., et al. (2000). Sleep, learning, and dreams: off-line memory reprocessing. Science.

- Hobson, J.A., Pace-Schott, E.F. (2002). The cognitive neuroscience of sleep: neuronal systems, consciousness and learning. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts