Why Eyewitness Testimony Is Less Reliable Than You Might Think

8 min read Explore why eyewitness testimony often falls short in accuracy and how it impacts criminal justice decisions. (0 Reviews)

Why Eyewitness Testimony Is Less Reliable Than You Might Think

Introduction

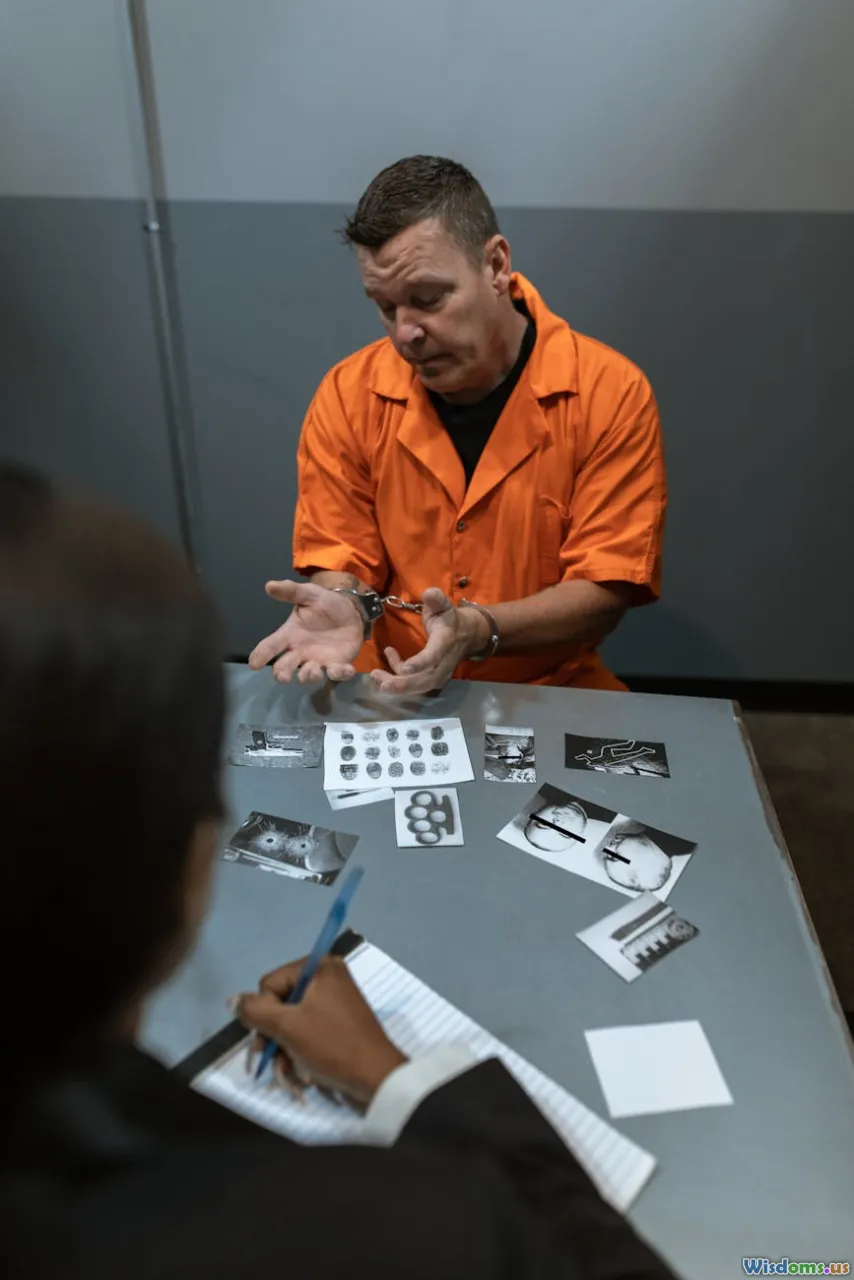

Imagine being certain you saw a crime. Your detailed account then leads to an arrest—yet years later, DNA evidence proves the accused innocent. This unsettling scenario is more common than many expect. Eyewitness testimony has long been regarded as a cornerstone of criminal justice, carrying immense weight in courts. But can memories eyewitnesses share really be trusted? Recent research in psychology and forensic science uncovers alarming limitations beneath the surface of these seemingly straightforward accounts. This article explores why eyewitness testimony is often less reliable than we assume and how this reality reshapes criminology and crime investigation today.

The Psychology Behind Eyewitness Memory

Memory Is Not a Video Recorder

One of the fundamental misconceptions about eyewitness testimony is the idea of memory as a perfect recording. In truth, human memory is reconstructive, not reproductive. Psychologists have found that memories are actively reconstructed each time they are recalled, making them malleable and prone to distortion.

Elizabeth Loftus, a pioneering memory researcher, famously demonstrated this in her 1974 ‘‘Lost in the Mall’’ experiment. Participants were led to believe they had been lost as children. Many ultimately ‘‘remembered’’ this fabricated event in vivid detail, highlighting the ease with which false memories can form. This research suggests that eyewitnesses can unintentionally misremember details or even events altogether.

The Role of Stress and Trauma

Criminal events are often high-stress situations. Stress can severely impair an eyewitness's ability to encode and retrieve accurate memories. The combination of fear, shock, or chaos can tunnel focus to certain elements like weapons—leaving other important details vague or incorrect. This phenomenon, known as ‘‘weapon focus effect,’’ has been confirmed in numerous studies.

For instance, a meta-analysis published in the Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition (2019) showed that witnesses under threat of harm identified perpetrators with significantly less accuracy than calm witnesses. This decrease in reliability complicates confidence in testimony gathered immediately after crimes.

Influence of Suggestion and Leading Questions

How questions are asked can alter an eyewitness’s memory. Loftus also showed that wording matters profoundly. In her well-known car accident study, people asked ‘‘How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?’’ estimated higher speeds and even reported seeing broken glass—which wasn’t present—more often than those asked using the verb ‘‘contacted.’’

Such suggestive questioning can implant or reshape memories. This makes post-event interviews a delicate process requiring neutral phrasing to avoid contaminating testimony.

Real-World Consequences of Unreliable Eyewitness Testimony

Wrongful Convictions and Exonerations

Eyewitness error is one of the leading causes of wrongful convictions. The Innocence Project, an organization dedicated to exonerating wrongly convicted individuals through DNA testing, reports that eyewitness misidentification played a role in over 70% of cases overturned by DNA evidence in the United States.

Consider the case of Ronald Cotton, who was wrongfully convicted in 1984 of rape based largely on mistaken eyewitness identification. He spent over a decade in prison before DNA evidence conclusively proved his innocence. His story underscores how reliance on faulty eyewitness accounts can devastate innocent lives.

Impact on Crime Investigations

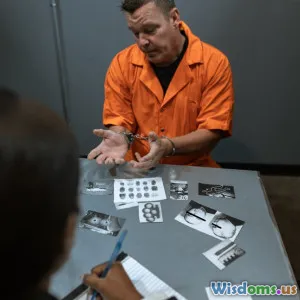

Inaccurate eyewitness accounts can misdirect investigations. Police might focus on innocent suspects or disregard viable leads. This not only wastes resources but also leaves actual perpetrators free to commit more crimes.

Eyewitnesses might be confident but incorrect. The confidence of the witness does not necessarily correlate with accuracy, a nuance often misunderstood by juries and legal professionals. Studies have found that jurors tend to give significant weight to confident testimony, which can lead to miscarriages of justice.

Advances to Mitigate Eyewitness Error

Improved Police Procedures

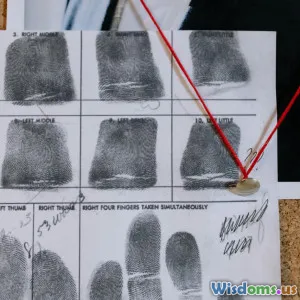

Understanding the pitfalls of eyewitness testimony has led to changes in how law enforcement conducts lineups and interviews. Double-blind lineups, where the administrator does not know the suspect, reduce inadvertent cues. Sequential lineups, presenting suspects one at a time, rather than all at once, help witnesses avoid guessing based on comparison.

The U.S. Department of Justice has recommended these procedures based on empirical research, promoting their widespread adoption to minimize wrongful identifications.

Educating Jurors and Legal Professionals

Some courts now allow expert testimony on memory reliability to educate juries about eyewitness errors, helping balance their evaluation of testimony against physical evidence.

Legal reforms in places like the UK have recognized the fallibility of eyewitness testimony, incorporating safeguards aimed at enhancing justice accuracy.

Technology Integration

Forensic technologies—like DNA testing and surveillance camera recordings—are increasingly supplementing or challenging eyewitness accounts. Such advancements provide objective data that can confirm or refute subjective testimony, reducing reliance on flawed memories alone.

Conclusion

Eyewitness testimony holds dramatic sway in courtrooms and investigations, yet science exposes significant weaknesses in its reliability. Human memory’s fragile and reconstructive nature, combined with environmental factors like stress and suggestive questioning, can produce inaccurate or false accounts. Real-world consequences of such errors are severe, often resulting in wrongful convictions.

Recognizing these limits spurred procedural reforms and the integration of new technologies that aim to prevent miscarriages of justice. As the criminal justice system evolves, it must continue embracing scientific insights and caution, ensuring that justice is founded on truth, not just confident recollection.

Understanding the intricate flaws of eyewitness testimony doesn’t diminish the value of human experience; it enriches investigation methods, driving continuous improvements to safeguard fairness and accuracy for all.

By delving beneath the surface of eyewitness claims, we not only question what we think we see but empower ourselves and the legal system to seek and uphold truly reliable evidence.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts