Why Historical Preservation Is Facing New Challenges Today

8 min read Explore why historical preservation is encountering unprecedented challenges in today’s rapidly changing world. (0 Reviews)

Why Historical Preservation Is Facing New Challenges Today

Preserving our architectural heritage has long been heralded as a bridge connecting us to our past, culture, and identity. Yet, in the 21st century, this noble pursuit is confronted by a shifting landscape full of complex and unprecedented challenges. From fast-paced urbanization to climate change, economic pressures, and evolving social values, historical preservation efforts must now navigate a minefield of obstacles that threaten not only physical structures but also the very meaning and relevance of cultural heritage.

In this article, we’ll explore the multifaceted reasons historical preservation is facing new challenges today and why adaptive, inclusive strategies are critical to safeguarding our past for future generations.

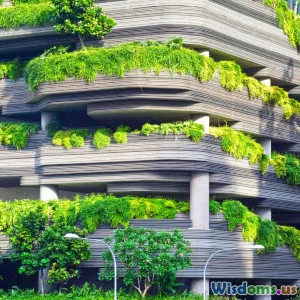

Accelerating Urbanization: The Space and Zeitgeist Crunch

One of the most visible and pressing threats to historic sites is rapid urban development. According to the United Nations, by 2050, nearly 68% of the world’s population will live in urban areas, intensifying pressure on land use, housing, and commercial infrastructure. This surge often places historic buildings and districts in the direct path of demolition or insensitive modification.

For example, in cities like New York, London, and Shanghai, real estate demand propels rapid construction projects that threaten heritage buildings. The historic Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong was demolished in the 1990s to make way for new development, reflecting how urgent economic interests often override preservation.

Furthermore, gentrification and socio-economic shifts alter neighborhoods’ cultural fabric, sometimes commodifying or displacing authentic historic communities. This fuels debates about what narratives get preserved and whose history is prioritized.

Climate Change: A Growing Threat to Historic Fabric

The impacts of climate change pose unprecedented risks to historic sites globally. Rising sea levels, increased flooding, wildfires, and extreme weather events directly damage or accelerate decay of architectural treasures.

Venice, Italy, is emblematic of this challenge. Its centuries-old canals and buildings face chronic flooding worsened by sea-level rise, leading UNESCO to warn of possible inscription as a “World Heritage in Danger.” Similarly, the ancient city of Timbuktu’s mud-brick structures confront erosion intensified by desertification and changing rainfall patterns.

Adaptation strategies require significant financial resources and innovative techniques—implementing flood defenses, using climate-resilient materials, or modernizing monitoring and maintenance—all of which strain preservation budgets and expertise.

Changing Social Values and Inclusion in Preservation

Preservation is no longer only about maintaining iconic landmarks tied to elite or colonial histories. Contemporary discourse demands inclusivity, recognizing marginalized voices and diverse cultural narratives. This shift challenges traditional preservation paradigms, which often favored monumental or aesthetically ‘valuable’ structures.

For instance, preservationists now prioritize safeguarding sites meaningful to Indigenous peoples, immigrant communities, LGBTQ+ histories, and working-class neighborhoods. The designation of places like the Stonewall Inn in New York—central to LGBTQ+ rights history—as a national monument underscores such expanded perspectives.

This evolution prompts questions about which sites deserve protection, how to interpret complex histories layered with trauma or controversy, and how to engage communities in participatory preservation efforts.

Economic Pressures and Funding Limitations

Despite the growing need for comprehensive preservation, funding remains chronically insufficient. Historic restoration projects often contend with tight budgets, competing priorities, and economic downturns.

Public funds for preservation can be inconsistent, as seen in the U.S. where federal tax credits for rehabilitation projects fluctuate with legislative policies. Private investment tends to favor commercially lucrative developments rather than costly preservation.

Moreover, maintenance of aging structures is an ongoing expense that many owners—especially for residential heritage properties—cannot sustain. This underfunding often results in neglect, deterioration, or inappropriate renovations that compromise historic integrity.

Technological Advances: Double-Edged Sword

Technology offers new tools like 3D laser scanning, digital modeling, and virtual reality to document and visualize historic sites. These can enhance preservation planning, education, and public engagement.

However, technology also accelerates threats. For example, online property listings and speculative trends can lead to rapid redevelopment of heritage neighborhoods. Additionally, social media’s viral nature can spur uncontrolled tourism to fragile sites, causing wear and management challenges.

Balancing technology’s benefits with mindful stewardship is essential to leveraging innovation without exacerbating harm.

Toward Adaptive and Sustainable Preservation

In response to these multifaceted challenges, preservationists advocate for adaptive strategies that recognize heritage sites as living entities intertwined with contemporary social, environmental, and economic dynamics.

Integrating Climate Resilience

Emphasizing climate adaptation within preservation is critical. Projects like the Thames Barrier upgrade in London and Amsterdam’s innovative water management showcase how infrastructure can protect historic urban centers from flooding.

Community Engagement and Equity

Genuine community inclusion ensures preservation reflects shared values and nourishes cultural continuity. Initiatives such as Detroit’s community-based heritage projects demonstrate how activating local voices can revitalize neighborhoods while respecting history.

Sustainable Materials and Practices

Using eco-friendly materials, reducing renovation waste, and implementing energy-efficient upgrades contribute to both preservation and environmental goals.

Policy Innovation and Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Combining urban planning, environmental science, social justice, and heritage conservation reshapes frameworks and funding models that better address contemporary realities.

Conclusion

Historical preservation today stands at the crossroads of tradition and transformation. The acceleration of urban growth, climate threats, evolving cultural awareness, and economic constraints combine to create an intricate web of challenges. Yet, this juncture also opens opportunities for innovation, inclusion, and sustainability.

Preserving our built heritage is no longer a solely nostalgic endeavor but a dynamic process requiring flexibility, community partnership, and forward-thinking leadership. Only by embracing these complexities can we ensure that the stories, artistry, and identities engraved in architecture endure as vital parts of our shared human experience.

The future of historical preservation depends on our capacity to adapt—and to value history not as a static monument, but as an ever-evolving dialogue across time.

References

- United Nations, World Urbanization Prospects, 2018 Revision

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Venice and its Lagoon

- National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, Stonewall National Monument

- The Climate Change and Historic Architecture Journal, 2022

- Sullivan, Lynne, “Preservation and Community: New Directions in Heritage Conservation” (2020)

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts