Why Science Needs More Pragmatist Thinking Today

13 min read Explores the necessity for pragmatist thinking to drive impactful, adaptive scientific progress in today’s complex world. (0 Reviews)

Why Science Needs More Pragmatist Thinking Today

Science stands at a crossroads. As society faces climate change, pandemics, technological disruption, and polarization, scientists find themselves balancing rigorous methods with immense ethical, practical, and political pressures. Rooted in centuries-old traditions of objectivity and precision, scientific inquiry often aspires to detached neutrality. Yet, the challenges of our era demand not only answers but workable solutions that accomplish real-world goals. Pragmatism—a rich philosophical tradition—is poised to infuse scientific culture with fresh vitality, relevance, and impact. But why does science, now more than ever, need more pragmatist thinking?

The Roots of Pragmatism

Pragmatism as a philosophy originated in late 19th-century America, shaped largely by figures like Charles S. Peirce, William James, and John Dewey. Unlike enlightenment rationalists who pursued absolute truths, pragmatists grounded knowledge in practical consequences and experiential outcomes. For instance, William James defined truth itself as "what works in the way of belief"—essentially, beliefs are true if they help us navigate our lives effectively.

This contrasts with science's ideal of value-neutral observation: reviewing results detached from the world they affect. While neutral empiricism allowed crucial discoveries, it has at times insulated science from urgency. Pragmatism's focus on consequences, context, and adaptability makes it uniquely suited to rejuvenate scientific culture. It urges us to anchor science in what matters: improving lives, solving pressing problems, and flexibly shifting methods based on real-world feedback.

A classic historical example lies in Louis Pasteur’s work on pasteurization and vaccination. Pasteur’s approach wasn't just scientifically inquisitive; it responded directly to immediate societal issues, such as spoilage and rabies outbreaks. His research was deeply entwined with citizen needs—a pragmatic approach years before the term was coined.

Pragmatist Principles in Modern Science

What does a pragmatist approach look like in contemporary science? First, it values experimentation and iterative problem-solving over dogmatic adherence to inherited theories. Secondly, it considers the consequences—social, ethical, practical—of scientific activity.

Take climate science, for example. Data and models are essential, but a pragmatist asks: What can we do now, given imperfect knowledge? This was evident in the formulation of the Paris Agreement. Scientists and diplomats had to mediate between ideal emissions targets and what was politically and economically feasible, reflecting pragmatism’s trademark blend of ideals and practicality.

Pragmatist science also values flexible, adaptive responses. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the development of mRNA vaccines (such as those by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna) started with basic research but rapidly pivoted to meet the urgent practical need. Researchers, manufacturers, and regulatory bodies acted expediently—temporarily relaxing conventional protocols while responding directly to an unfolding global crisis. The shift toward an "all hands on deck" ethos showed a pragmatic prioritizing of life-saving outcomes over strict, tradition-bound processes.

Overcoming the Myth of Pure Objectivity

Science frequently mythologizes objective, neutral pursuit. While the rigorous collection of evidence is vital, proclaiming science as value-free misses how societal needs, funding, and ethical decisions shape research in practice.

Pragmatist thinking surfaces these value judgments, pushing scientists and policymakers to address them transparently. For example, the framing and funding of medical research often reflects broader social priorities: why, for instance, do certain diseases (like rare childhood conditions) struggle to receive investment, while others (such as adult chronic diseases) attract substantial funding?

Admitting such value-laden realities does not undermine scientific credibility—on the contrary, a pragmatic orientation fosters honest debate about competing priorities, resource allocation, and the acceptance of scientific uncertainty. The field of bioethics emerged from such a pragmatist impulse, recognizing that dilemmas in medicine and biotechnology required balanced, situational reasoning instead of fixed rules.

Pragmatist thinking thus encourages a reflective science—less hobbled by mythical objectivity and better suited for addressing urgent, complex problems.

Fostering Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Modern problems—climate change, pandemic preparedness, artificial intelligence—are increasingly interwoven across traditional disciplines. Pragmatism's stress on what "works" in particular contexts naturally drives collaboration. Instead of elevating methodological purity, scientists build alliances spanning physics, biology, engineering, economics, psychology, and beyond.

A robust example is in public health research, which employs epidemiologists, behavioral scientists, statisticians, community organizers, and communication specialists. During mass vaccination campaigns, a strictly medical approach (focusing on biological efficacy) often fails if it ignores pragmatic questions about access, hesitancy, communication styles, and cultural context. Only by crossing disciplinary boundaries—adapting strategies based on real-time community feedback—do such efforts achieve their aims.

Similarly, the explosion of research in renewable energy brings together materials scientists, economists, systems engineers, urban planners, and even behavioral scientists. Pragmatist values drive these fields to focus less on disciplinary silos and more on optimizing for changes that make measurable improvements in energy transport, affordability, and environmental outcomes.

By emphasizing direct problem-solving, science becomes less about maintaining traditional boundaries and more about assembling teams to tackle the world's toughest challenges with creativity and resilience.

Science Communication and the Public

In the internet age—where misinformation spreads rapidly and scientific mistrust is high—a pragmatist perspective reshapes how scientists engage with the public. Traditional science communication focused primarily on broadcasting findings, assuming facts alone would change minds. However, a pragmatist approach recognizes that scientific understanding is as much about trust, relationship-building, and listening as it is about information transfer.

Take the challenge of vaccine hesitancy. Pragmatism inspires a shift from didactic lectures to dialogical, community-centered engagement. The World Health Organization’s “Listen, Understand, Engage” approach—employed during Ebola and COVID-19 vaccination drives—mirrors pragmatic priorities: actively listening to concerns, recognizing local experiences, and crafting messages that address tangible needs.

Pragmatist thinking also values humility. It acknowledges that public skepticism can reveal legitimate concerns, calling scientists to build alliances rather than blame audiences for ignorance. This realigns scientific messaging—encouraging public involvement in shaping research priorities and fostering trust through practical partnerships.

Adaptability in the Face of Uncertainty

All scientific fields confront incomplete knowledge and unpredictable variables. Pragmatism flourishes in uncertainty by treating it not as a barrier, but as a prompt for proactive, trial-and-error adaptation.

Consider evolutionary biology, which posits no fixed plan—only continual adjustment to shifting environments. Pragmatic reasoning in science similarly prizes strategies that work "well enough for now," revisable as new insights and circumstances emerge. This stands in opposition to the search for a single, absolute solution before taking any action—a tendency that can paralyze urgent policy and intervention.

This virtue is starkly evident in crisis management, such as pandemic response or disaster mitigation. Governments and agencies that engage in scenario modeling (accepting that predictions are ranges, not binaries), pilot-programming (testing policies before full-scale rollout), and iterative improvement demonstrate practical wisdom. For example, many successful municipalities tackling urban air pollution have relied upon pragmatic cycles of implementation, measurement, community feedback, and retooling, rather than awaiting an "ideal" policy.

Ethical Implications: Science for the Common Good

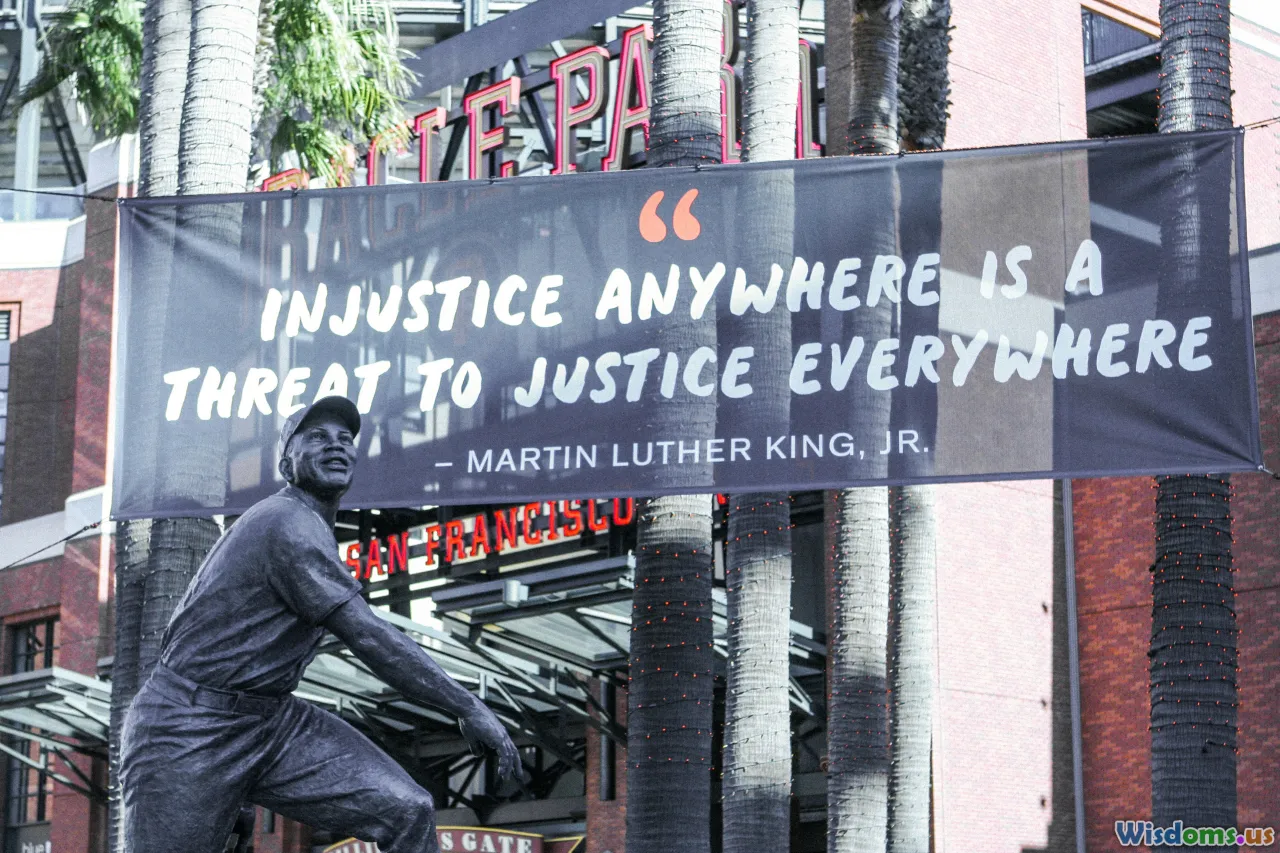

Science's traditional detachment does not exempt it from the ethical demands of plural societies. Pragmatism underscores that scientific choices are not just technical but inherently moral—they shape who benefits, who is at risk, and whose voices are heard.

Take the debate over genetically modified crops (GMOs). Pragmatism calls for pushing beyond polarizing "yes/no" frameworks, seeking outcomes that maximize public good while minimizing harm. That means engaging stakeholders, adapting policies in light of evolving evidence, and foregrounding conduct over inflexible dogma. This is not moral relativism, but a commitment to shared problem-solving and maximizing net benefit.

Classical pragmatists like John Dewey constructed models of science education that equipped citizens to actively interrogate the values underlying research. Modern scientific authorities—from the National Institutes of Health to the World Health Organization—are adopting similar principles, advocating for co-design and consultation in medical trials, environmental interventions, and urban planning. This broadens science’s relevance while ensuring its outputs promote justice, inclusion, and common-good outcomes.

The Future: Toward a Pragmatic Scientific Culture

A more pragmatist science is forward-looking—responsive, entrepreneurial, and public-minded. The increasing pace of crises and technological change will only intensify demand for relevance and adaptability.

A paradigm of pragmatic science would:

- Emphasize outcome-based targets, iteratively refined as circumstances shift.

- Reward interdisciplinary teamwork over insular, status-driven individual achievement.

- Prioritize community input and lived-experience data alongside abstract theory.

- Practice ongoing reflection, revision, and honest disclosure about uncertainty.

- Center its ethical compass on the well-being of people and planet.

Pragmatist philosophy does not call for abandoning scientific rigor or expertise. Rather, it asks scientists to anchor their work in concrete, positive transformation—making every experiment, collaboration, and communication channel deliver not just knowledge, but real hope and shared progress. In return, science can cultivate much deeper public trust and, crucially, remain a force for good in turbulent times.

By embracing pragmatist thinking, science reaffirms its most profound purpose: to know in order to improve—the ultimate test, now and always, of any society’s intelligence and compassion.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts