Why Walkability Is the Most Underrated Urban Design Metric

8 min read Discover why walkability stands as the most underrated urban design metric, reshaping livability and sustainability in cities worldwide. (0 Reviews)

Why Walkability Is the Most Underrated Urban Design Metric

Walkability—we often hear the term, but rarely grasp its profound impact beyond the surface. Imagine a city where errands, social meetings, and daily exercise seamlessly integrate into a short, safe stroll. This isn’t just a luxury but a transformative force shaping healthier, more sustainable, and vibrant urban environments. Yet, in the busy grind of modern urban planning, walkability remains the unsung hero, overlooked in favor of metrics like transit ridership or traffic flow.

This article dives deep into why walkability should be the crown jewel of urban design metrics. We will explore its significance through lenses of health, economic prosperity, environmental wellbeing, and social connectivity. We will also illustrate these points with real-world examples and data, urging architects, planners, policymakers, and citizens alike to reframe their perspective on urban metrics.

Defining Walkability: More Than Just a Walk

At its core, walkability measures how friendly an area is to walking. This involves several key components:

- Safety: Are pedestrian pathways safe from traffic and crime?

- Accessibility: Can residents easily reach amenities like shops, schools, and parks on foot?

- Comfort and Convenience: Are sidewalks well-maintained, shaded, and inviting?

- Connectivity: How well do paths and streets connect different zones?

While simple to define, these elements interrelate to enhance or degrade urban life quality remarkably.

The Hidden Benefits of Walkability

1. Public Health Booster

Walking as daily exercise reduces risks of heart disease, obesity, diabetes, and depression. A 2015 study published in The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health found that residents living in walkable neighborhoods had a 35% lower risk of weight gain.

Take Copenhagen, Denmark, often hailed as the gold standard of walkability and cycling. Its thoughtful urban infrastructure encourages walking, directly correlating with its status as one of the healthiest cities globally.

2. Economic Vitality and Local Business Growth

Walkable neighborhoods attract more foot traffic, creating vibrant street economies. According to the National Association of Realtors, 78% of millennials would choose to live in walkable communities, correlating with increased demand and spending near pedestrian-friendly areas.

Case in point: Portland, Oregon’s Pearl District transitioned from an industrial area to a walkable urban hotspot, catalyzing local businesses, rising property values, and tourism.

3. Environmental Sustainability

Every mile reduced from car travel cuts carbon emissions and air pollution. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) notes that compact, walkable communities result in up to 30% fewer greenhouse gas emissions per household.

For example, cities like Vancouver, Canada, with effective walkable infrastructure, have seen measurable drops in per capita carbon footprints.

4. Enhanced Social Interactions

Walkable neighborhoods foster communal bonds. Informal encounters on sidewalks and parks build social capital, reducing isolation and fostering civic engagement.

Jane Jacobs famously argued how 'eyes on the street' via walkability enhance safety and community cohesion—a social dynamic largely absent in car-centric suburbs.

Why Walkability Is Overlooked Despite Its Impact

Focus on Automotive Infrastructure

The dominance of car culture and freeway expansion since the mid-20th century shifted priority away from pedestrian infrastructure. Urban sprawl, with vast distances between destinations, has made walkability a challenge in many cities.

Difficulties in Quantification

Unlike traffic counts or transit usage, walkability is multi-dimensional and context-dependent, making it harder to measure precisely. However, tools like the Walk Score have popularized walkability ratings using data on amenities and pedestrian friendliness.

Conflicting Stakeholder Interests

Businesses favoring large parking lots, developers focused on car-accessible projects, and policy inertia often delay walkability investments.

Encouraging Walkability: Urban Design That Works

Integrating Mixed-Use Development

Mixed-use neighborhoods cluster residential, commercial, and recreational uses, shortening walking distances. New York City's Hudson Yards exemplifies this successful integration fostering high walkability even in dense urban settings.

Prioritizing Pedestrian Infrastructure

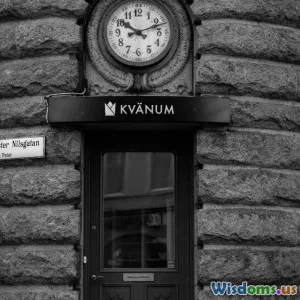

Sidewalk expansions, protected crosswalks, street furniture, lighting, and traffic calming measures promote safe and inviting pedestrian spaces. Barcelona’s implementation of ‘superblocks’ reduces car traffic and expands pedestrian zones, improving walkability dramatically.

Green and Open Spaces

Parks and green corridors, such as the High Line in NYC, entice residents outdoors, increasing walkability and urban nature access.

Smart Urban Policy and Community Engagement

Policies incentivizing walkability and involving residents in planning result in designs that truly meet pedestrian needs. For instance, the Complete Streets initiative in many U.S. cities mandates street designs that accommodate all, not just cars.

Conclusion: Elevating Walkability in Urban Priorities

Walkability is a transformative urban design metric that touches health, economy, environment, and social fabric profoundly. Yet its multidimensional nature and historical car dominance have left it underappreciated.

Cities that commit to walkable design unlock significant benefits: reduced chronic disease rates, thriving local economies, lower carbon footprints, and stronger communities. Planners, architects, and policymakers must adopt walkability as a central priority—not an afterthought.

In a future of climate urgency and urban growth, enhancing walkability is not just ideal; it’s essential. As Jane Jacobs quoted, “The city is not an accident but the result of coherent visions and policies.” It’s time that walkability takes center stage in those visions.

References:

- International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2015

- National Association of Realtors, Millennial Homebuyers Report 2019

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Urban Transportation Fact Sheet

- Jacobs, Jane. "The Death and Life of Great American Cities." 1961

- Walk Score methodology: https://www.walkscore.com/methodology.shtml

- Case studies from Copenhagen, Portland, Vancouver, Barcelona, NYC

By reimagining urban spaces through the walkability lens, we weave sustainability, livability, and community into the very fabric of city life.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts