Exploring Sacred Pilgrimages in Buddhism and Islam

15 min read A comparative look at pilgrimage traditions in Buddhism and Islam, exploring sites, rituals, and spiritual significance. (0 Reviews)

Exploring Sacred Pilgrimages in Buddhism and Islam

Pilgrimage has shaped spiritual landscapes for centuries, guiding millions of followers across continents and generations. In both Buddhism and Islam, sacred journeys are more than a tradition—they are intimate, transformative rites that deepen spiritual understanding and bind the faithful to the roots of their religion. This exploration delves into these revered pilgrimages, uncovering their origins, rituals, and enduring impacts on modern devotees.

The Origins and Purpose of Pilgrimage in Buddhism and Islam

The concept of pilgrimage, or traveling to a sacred site for spiritual enrichment, has unique manifestations in Buddhism and Islam—two world religions shaped by different cultures and epochs yet aligned in their pursuit of enlightenment and closeness to the divine.

Buddhist Pilgrimage:

Buddhists undertake pilgrimages to sites associated with milestones in the life of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha. The earliest records, dating back to around 3rd century BCE during the reign of Emperor Ashoka, highlight four primary pilgrimage sites:

- Lumbini (birthplace, in present-day Nepal)

- Bodh Gaya (where Buddha attained enlightenment, India)

- Sarnath (where he delivered his first sermon, India)

- Kushinagar (where he achieved parinirvana, death, India)

Ashoka, in particular, championed the practice, erecting pillars and stupas to mark these spots and encourage followers. For Buddhists, such journeys are opportunities to accumulate merit, reflect on the impermanence of life, and strengthen their resolve on the path of dharma.

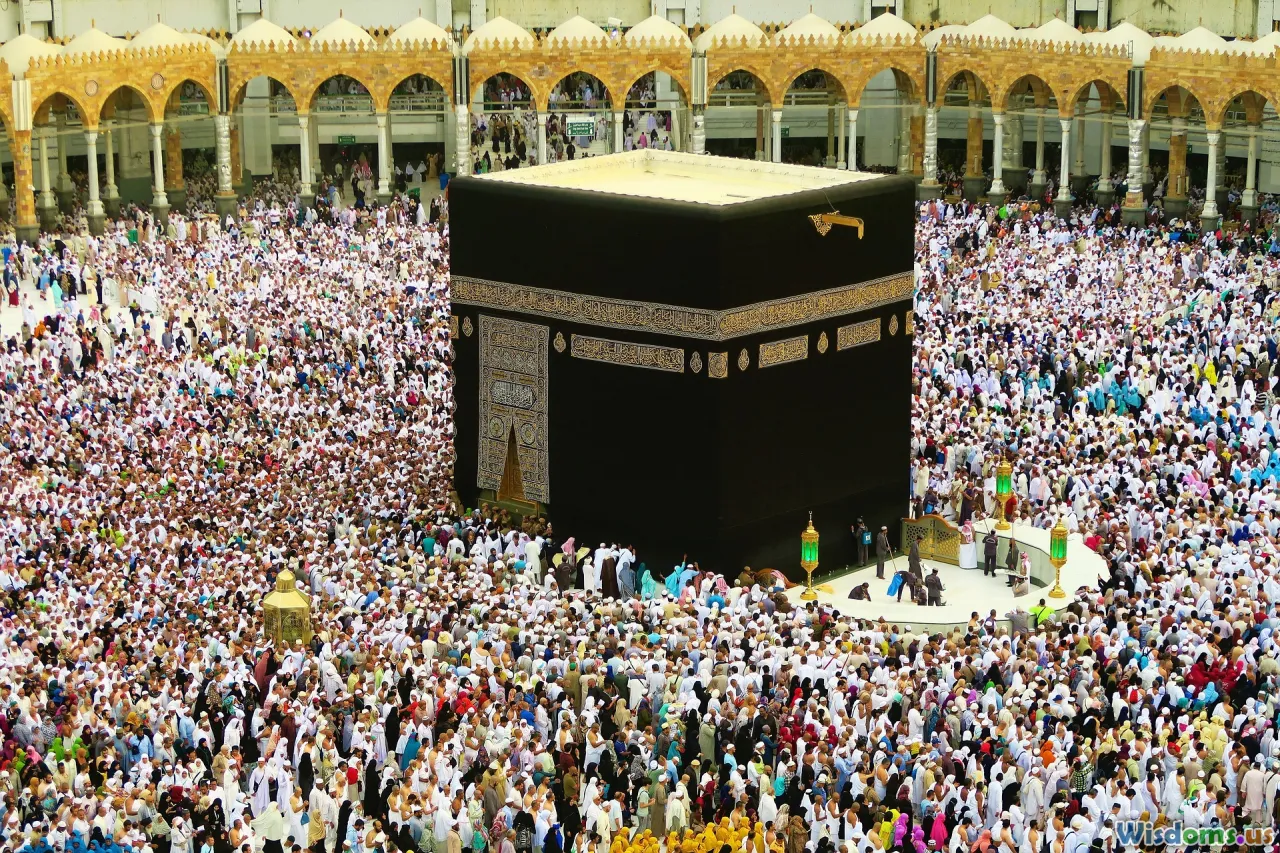

Islamic Pilgrimage:

In Islam, the Hajj to Mecca is a foundational pillar, incumbent upon every able Muslim once in a lifetime (Quran 3:97). Mecca’s sacred precinct has drawn believers since the advent of Islam in the 7th century CE, but its roots run deeper—a site claimed to date back to the Prophet Abraham and his son Ishmael. Additionally, Muslims may undertake Umrah, a lesser pilgrimage outside the strict days of Hajj, or visit other holy towns like Medina and Jerusalem.

Both pilgrimages embody the essence of sacred movement—journeying both outward and inward, abandoning routine comfort for timeless meaning.

Rituals and Stages of the Buddhist Pilgrimage Experience

A Buddhist pilgrimage is not merely a sightseeing tour, but a structured spiritual discipline imbued with ritual, history, and profound symbolism.

How Buddhists Prepare and Travel:

Preparation involves purifying intentions and heart: many spend weeks or months preparing, studying the Buddha’s teachings, and consulting with senior monks. Some choose arduous journeys on foot to foster humility and devotion. Traditional attire—white clothing or simple robes—signals their spiritual commitment.

The Four Sacred Sites in Action:

- Lumbini: Pilgrims circumambulate the Maya Devi Temple, light candles, and reflect under the bodhi tree where the Buddha’s mother is believed to have rested. Inscriptions in multiple languages—Sanskrit, Brahmi scripts—reflect its global spiritual magnetic pull.

- Bodh Gaya: At the Mahabodhi Temple, queues of robe-clad pilgrims prostrate, meditate for hours beneath the descendant of the original Bodhi tree, and join global chanting sessions. Many leave offerings of lotus flowers or yellow robes.

- Sarnath: Here, the atmospheric Dhamek Stupa is surrounded by prayer flags and wheels. Practitioners reread the First Sermon (the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta) and participate in walking meditations.

- Kushinagar: Night vigils and pujas (prayer rituals) mark the Buddha’s final liberation. Offerings of incense and butter lamps illuminate the intricately carved reclining Buddha statue.

Significance of Each Stage:

Every site invites reflection upon a core tenet: birth, enlightenment, teaching, and death. Together, they encapsulate the entire Buddhist path, providing pilgrims with a direct, immersive lesson in impermanence and the Eightfold Path.

Concrete example: Japanese and Sri Lankan pilgrims often recite local prayers alongside the softer Pali chants of Burmese practitioners—showcasing Buddhism’s cross-cultural tapestry.

The Hajj: A Lifetime Obligation and Its Universal Symbols

If the Buddhist journey is about stages of awakening, the Hajj is a grand assembly—a singular event with a choreography of its own.

Travel and Entry Rites:

Muslims prepare spiritually and materially months before departure, asking for forgiveness from family and repaying debts. Once at the brink of Mecca, they don two pieces of unsewn white cloth called ihram (for men; women adopt simple, plain clothing) symbolizing purity and the equality of all before God.

The Six-Day Sequence:

Over six intensely packed days, Hajjis circle the Kaaba (the cube-shaped center of Islam’s holiest mosque), trod the path between Safa and Marwah, stand in prayer at the plain of Arafat—site of Prophet Muhammad’s Farewell Sermon—collect pebbles at Muzdalifah, and stone the Jamarat pillars at Mina (reenacting Abraham’s rejection of Satan’s temptations).

One of the most poignant moments occurs at Arafat: over two million worshippers stand shoulder to shoulder, centuries erasing lines of nationality, wealth, and race. The air thickens with supplication—scholars compare this to a rehearsal for the Day of Judgment, emphasizing humility and repentance.

Concluding the Ritual:

Sacrifice of an animal (commonly a sheep or goat) marks the conclusion, followed by a return to Mecca for a final circumambulation—Tawaf al-Ifadah. Many also visit the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, though this is not strictly part of Hajj.

Inner Transformation: The Spiritual Psychology Behind Pilgrimage

While outwardly dramatic, pilgrimage is inwardly transformative. Participants frequently report profound changes in their sense of self and their relationship to others and the divine.

In Buddhist practice, the journey’s hardship is seen as an aspect of purification. Quiet reflection—walking barefoot, enduring heat or cold, sleeping in humble lodgings—deliberately strips away ego and luxury. The journey’s difficulties mirror the nature of samsara, inspiring travelers to embrace the middle path. One Thai monk wrote: “My feet ached, but my heart was light with the teachings of the Buddha.”

In Islam, the uniformity of ihram clothing and shared hardship—crowded tent cities, bursts of emotional outpouring—accentuate the core tenet of ummah, or spiritual brotherhood. The Hajj fosters humility and thankfulness, reminding Hajjis of the finite nature of earthly existence and the centrality of surrender to God. Post-Hajj, many choose to forgive old rivals, take up charity, or realign their lives more closely with Islamic ethics.

Concrete example: In a 2020 study published in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, researchers found that 58% of South Asian Buddhists reported a "greater sense of peace and acceptance of impermanence" after a major pilgrimage, while among Hajj returnees, over 70% felt "more connected to God and the global Muslim community" than before.

The Social and Global Dimensions of Sacred Travel

Pilgrimage is personal, but it’s also deeply communal. Over centuries, it has served as a cross-cultural magnet, a generator of art, music, and global solidarity.

Gathering of Nations:

Both Buddhist festivals—like the Kagyu Monlam Chenmo in Bodh Gaya—and the Hajj become microcosms of the world in one place. For example, during the 2023 Hajj, over 2.5 million pilgrims from more than 180 countries converged on Mecca, communicating in hundreds of languages.

In Buddhist centers such as Bodh Gaya, visitors now find teahouses run by Chinese lay groups, Japanese calligraphy workshops, and Korean chanting troupes joining local Indian ceremonies. Such eclectic convergences give rise to interfaith and intercultural friendships, while also transferring unique religious songs, crafts, architecture, and food.

Support Systems and Networks:

Pilgrimage has also spurred economic and social networks—supporting travel infrastructure, publishing guidebooks, and founding welfare institutions. Notably, ancient Buddhist sites such as Sarnath evolved as centers for not only worship but also education and healthcare by the 5th century. In Mecca, specialized agencies now provide translation, healthcare, and logistical support to ease the journey for non-Arabic-speaking pilgrims.

In addition, both traditions have networks for supporting less fortunate devotees. Islamic charities routinely sponsor underprivileged Muslims for Hajj, while Buddhist monasteries often cover travel for elderly or novice monks.

Challenges and Controversy: Pilgrimage in a Modern World

Despite its benefits, modern pilgrimage has drawn debate and creative problem-solving.

Safety and Security:

The sheer scale, especially in Islamic Hajj, has sparked concerns over crowd control and safety. High-profile stampedes and heat-related illnesses have led Saudi authorities to implement electronic ticketing, crowd limits, and advanced healthcare monitoring.

Environmental Impact:

Millions of visitors lead to waste, pollution, and strain on local resources. In India, Buddhist organizers have introduced eco-conscious rituals—offering cloth bags instead of plastic at Bodh Gaya, for example. In Mecca, water and energy conservation programs accompany major pilgrim seasons, but experts say further progress is needed.

Accessibility vs. Spiritual Depth:

Some traditionalists fear commercialization or tourism dilutes the sacredness of pilgrimage; for instance, the proliferation of luxury hotels near holy sites raises concerns over equity and humility. Buddhist monastics worry that selfie culture distracts from spiritual cultivation, while in Islam, debates arise about the fairness of quotas and rising travel costs. Pilgrims are encouraged to focus on the inner dimension, use technology responsibly, and advocate for inclusivity.

Timeless Lessons: What Modern Seekers Can Learn

What can individuals today, spiritual or secular, draw from these enduring journeys?

-

Purposeful Travel: Pilgrimage invites mindful movement—traveling with explicit intention to grow. Choosing even local sites (a serene natural landscape, an ancestral grave, a community center) can be a modern reimagining of this tradition.

-

Humble Reflection: Stripping away comfort, committing to simplicity, and savoring each step in a purposeful way can foster resilience and perspective, regardless of one’s religious affiliation.

-

Solidarity and Generosity: The gatherings at Mecca or Bodh Gaya remind us of shared humanity and the importance of serving others on life’s journey. Group volunteering, charitable giving, and participating in cross-cultural events carry this spirit into daily life.

-

Embracing Diversity: Sacred travel is living proof that faith can unite people beyond borders. Modern pilgrimage highlights the beauty in diversity—and the strength in collective worship or contemplation.

Pilgrimage, be it Buddhist or Islamic, doesn’t end at the final shrine or stone. It is a way of seeing the world and oneself with renewed reverence—with every return, a fresh opportunity to step forward on a greater journey within.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts