The Rise of Secret Religious Groups in History

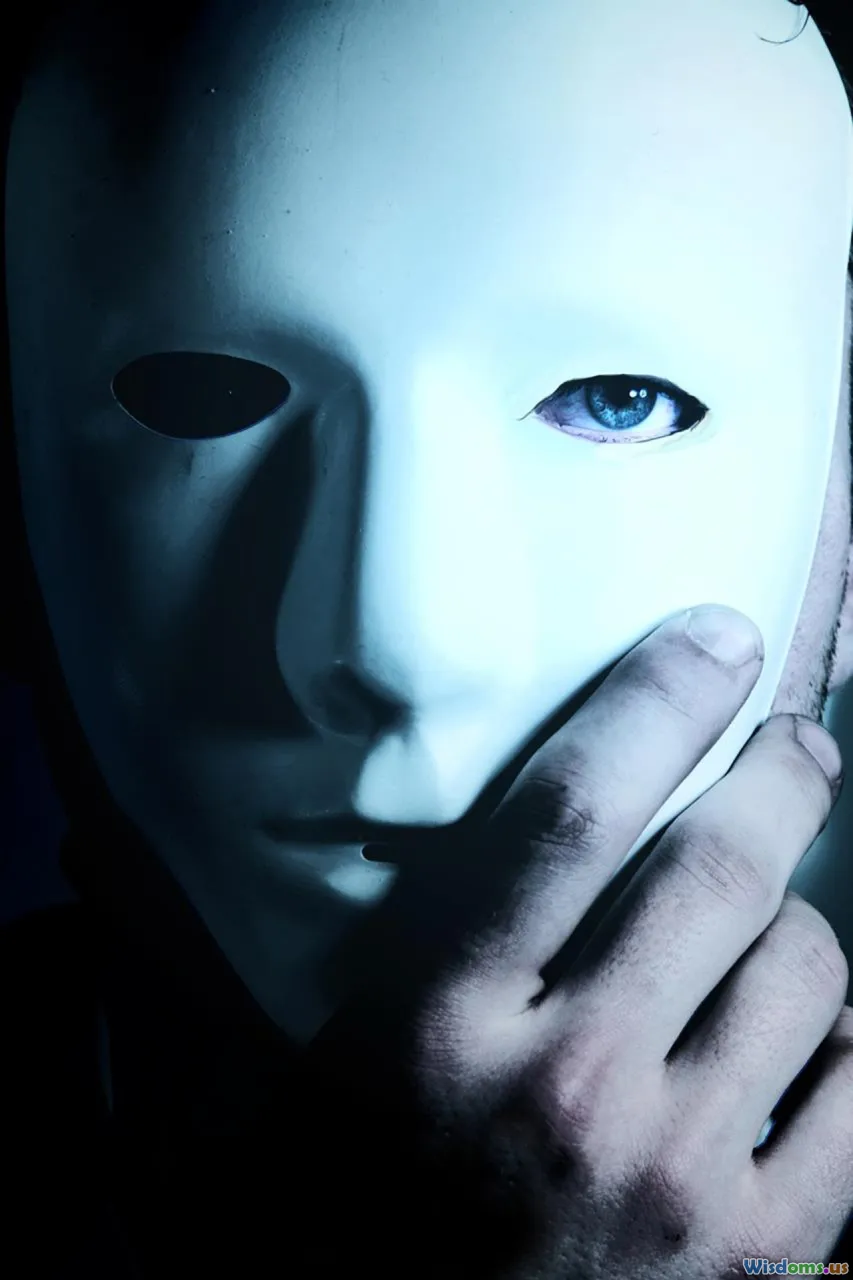

30 min read Explore how secret religious groups—from Eleusinian Mysteries and Mithraism to Cathars and hidden Christians in Japan—emerged under persecution, protected doctrine, and shaped law, culture, and power. (0 Reviews)Secrecy and religion have traveled together for as long as people have gathered to search for meaning. Sometimes, the hiddenness is protective: a shield against persecution or a way to preserve fragile community memory. Other times, secrecy is part of the ritual technology itself, guarding a mystery that is meant to transform initiates and only initiates. From ancient Mediterranean cults to underground chapels in Edo-period Japan, and from medieval sects to early modern panics about clandestine brotherhoods, secret religious groups have risen repeatedly, learned to adapt, and left traces that still fascinate.

The growth of these groups is not a simple story of concealment. It is about how rituals travel under pressure, how communities encode their deepest commitments into everyday objects, and how rumor often does as much to shape the record as the hidden rites themselves. Understanding the rise of secret religious groups means taking seriously both the very real risks their members faced and the alluring power of a shared mystery.

Why Groups Go Underground

There are three broad reasons why religious groups adopt secrecy: survival, sanctity, and structure.

- Survival: When the state or the majority culture treats a faith as subversive, secrecy becomes a defensive tactic. The Roman Senate’s crackdown on the Bacchanalia in 186 BCE pushed Dionysian worship into the shadows. In early modern Iberia, Jews and Muslims who had been forcibly converted to Christianity practiced aspects of their ancestral faith covertly to avoid the Inquisition’s surveillance. In late Tokugawa Japan, Christianity was outlawed, and believers risked punishment if caught; secrecy kept practices alive until the ban was lifted in the 19th century.

- Sanctity: Some traditions teach that sacred knowledge loses its transformative power when profaned. The Eleusinian Mysteries in ancient Greece guarded ritual details for nearly two millennia on the belief that silence preserves awe. Many esoteric systems, from Kabbalah to Vajrayana Buddhism, restrict certain teachings not to form a cabal but to ensure proper preparation.

- Structure: The architecture of a secret group often reinforces identity. Initiation grades, passwords, and symbolic acts bind members together. Mithraism in the Roman world famously used a ladder of ranks and a scripted initiation that created a shared journey; the structure was the glue.

Secrecy often emerges from a blend of these. In times of threat, groups turn protective forms of secrecy into an art. In times of relative peace, those same techniques can deepen the bonds of belonging or sustain a mystique that draws in seekers.

Antiquity: Mystery Cults and Esoteric Schools

The ancient Mediterranean gave us the template for secretive religion as a recognized social form. The most enduring example is the Eleusinian Mysteries, centered near Athens and focused on Demeter and Persephone. For centuries, initiates walked the Sacred Way, participated in rites that promised a blessed afterlife, and swore an oath to reveal nothing. Modern historians still debate the content—possibly a mixture of fasting, sacred drink, and reenactment—but the secrecy itself is one of the best-attested facts. Importantly, Eleusis was not clandestine in the sense of illegal; it was a public institution with private rites. That distinction explains why it could last so long, likely until late 4th or early 5th century CE, when non-Christian rituals declined under imperial policy and invasions.

Other Greek-associated currents mixed philosophy with ritual secrecy. Pythagorean communities in southern Italy during the 6th–5th centuries BCE held teachings on number and harmony in reserve, used signs of recognition, and enforced strict ethical disciplines. Their semi-monastic lifestyle and inner-outer circle model made secrecy part of the method of moral formation.

Rome alternated between tolerating and fearing secret rites. The Senate’s decree against the Bacchanalia in 186 BCE accused the cult of wild nocturnal gatherings and unlicensed oaths. Scholars today view the decree as a moral panic triggered by the spread of a popular ecstatic rite that empowered the marginal and potentially destabilized established authority. The crackdown did not erase Dionysian worship so much as push it into more private, regulated forms.

By the empire’s height, Mithraism had become a vivid example of how secrecy could flourish in semi-public spaces. Mithraea—intimate cave-like chapels—appear across Roman garrisons and cities from Britain to Syria. Their iconography shows Mithras slaying a bull, flanked by torchbearers and a swirl of zodiacal symbols. Initiation grades (often listed as Corax, Nymphus, Miles, Leo, Perses, Heliodromus, Pater) created a ladder of spiritual ascent. The exclusivity—largely male, often soldierly—built cohesion. While not illegal, the rites were hidden from non-initiates, making Mithraism a textbook case of secrecy as sanctity and structure.

Underground Faith in Times of Persecution

When threat looms, secrecy becomes survival technology. The pattern recurs across continents and centuries.

-

Early Christians under Roman rule sometimes met in private homes, cemeteries, or catacombs. Modern scholarship cautions against the romantic idea that believers lived in subterranean warrens; catacombs were burial places first. Yet clandestine elements existed: symbols like the fish (ichthys, an acronym for Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior) could quietly signal allegiance. Periodic persecutions in the 3rd century CE, and local crackdowns before that, made low-profile worship prudent.

-

In the Arabian Peninsula before Islam’s expansion, the first Muslims met discreetly in Mecca, reportedly gathering in the house of al-Arqam to avoid the ire of local elites. Their secrecy served protection and cohesion until the political tide turned.

-

In Iberia from the late 14th century onward, waves of forced conversion and expulsion forced Jews and Muslims into the shadows. Many Jewish families who became New Christians (conversos) practiced elements of Judaism covertly—such as lighting Sabbath candles inside closed cupboards, avoiding pork under the guise of personal taste, or reciting prayers in private. The Spanish Inquisition, established in 1478, targeted judaizing and maintained networks of informants; its records show both continuity of practice and the pressures that distorted it. Moriscos, Muslims forcibly converted to Christianity in the early 16th century, similarly kept aspects of Islamic practice alive behind closed doors. Some memorized Arabic prayers phonetically in the Latin alphabet; others maintained dietary rules and life-cycle customs. Expulsions from 1609 onward scattered communities, but cultural memory persisted.

-

In Japan, the ban on Christianity starting in 1614 birthed the Kakure Kirishitan—Hidden Christians who practiced in secret until the ban’s end in 1873. They ingeniously transformed religious objects to deflect suspicion. Statues of the bodhisattva Kannon doubled as veiled images of Mary (Maria Kannon). Household shrines hid crosses behind sliding panels. The faithful memorized orasho, prayers whose sound preserved fragments of Latin and Portuguese through oral transmission. A brutal test, the fumi-e, forced suspected Christians to step on images of Christ or Mary; hesitation meant investigation. When a group of hidden believers revealed themselves to a French priest in Nagasaki in 1865, the world learned that centuries of concealed practice had preserved identity against the odds.

-

Sufi orders at times practiced in protected enclaves or went quiet under hostile regimes. The Bektashi order, for instance, faced suppression in the Ottoman Empire after the 1826 Auspicious Incident that disbanded the Janissaries; Bektashi lodges were closed, and adherents maintained a diffuse, semi clandestine presence until later revival.

Each of these cases illustrates tactics that recur: disguising sacred images, reshaping rituals for domestic contexts, encoding prayers in local languages, and trusting the power of memorized liturgy when texts are too risky to keep.

Esotericism vs. Secrecy: Drawing the Line

Not all guarded teaching equals clandestine community. Esotericism is a pedagogical boundary: some knowledge is restricted to those who are prepared, initiated, or mature. Secrecy in the sociological sense is a boundary against outside observation because of danger or stigma.

-

Esoteric examples: Kabbalistic study traditionally required a foundation in Jewish law and was often reserved for older students. Vajrayana Buddhism requires empowerment from a qualified teacher before practicing certain tantras. In both cases, the community can be public while particular transmissions remain private.

-

Clandestine examples: Crypto-Jews in Iberia or Hidden Christians in Japan formed networks not primarily to preserve an inner meaning but to avoid punishment. Their rituals moved from synagogues or churches to kitchens and storerooms; the line between public and private became a shield.

The two, of course, can overlap. Mystery cults like Eleusis made secrecy a sacred duty; in times of persecution, that duty becomes survival strategy. Distinguishing the motives helps explain why some secret groups endure peacefully for centuries and others dissolve as soon as danger passes.

The Middle Ages and Early Modern: Heresy, Orders, and Inquisitions

From the 12th to 17th centuries, Europe and the Near East witnessed an array of movements labeled heretical or seditious, often forcing communities to adopt flexible, hidden structures.

-

Cathars and Waldensians: The Cathars of Languedoc espoused a dualist theology and developed a network of itinerant preachers and sympathizers. As crusade and inquisition intensified in the 13th century, meetings migrated to farmhouses and forests. Waldensians, who emphasized apostolic poverty and lay preaching, were similarly pushed to the margins, later surviving in Alpine valleys where geography aided discreet worship.

-

Nizari Ismailis and the myth of the Assassins: The Nizari Ismailis established mountain fortresses such as Alamut in the late 11th century under Hasan-i Sabbah. Western crusader and later Orientalist accounts popularized lurid stories of hashish-fueled killers. Modern scholarship emphasizes political strategy over sensationalism. The Nizaris did employ targeted killings (fedai missions) as a tool of survival in a hostile environment dominated by larger Sunni polities, while developing a theology that permitted dissimulation (taqiyya) under threat. The Mongol invasion destroyed Alamut in 1256, dispersing the community yet not erasing it.

-

Knights Templar: Founded around 1119 to protect pilgrims, the Templars grew wealthy and attracted suspicion. King Philip IV of France, seeking debt relief and control, arrested them in 1307 on charges of heresy and illicit rites. Many confessions were extracted under torture. The order was dissolved by 1312. The episode seeded centuries of rumors about secret Templar knowledge. The lesson is less about actual clandestine rites and more about how states can weaponize secrecy allegations.

-

Rosicrucian manifestos: Beginning in 1614, anonymous pamphlets in German lands announced a brotherhood of enlightened Christians dedicated to reform. Whether the fraternity existed as described is doubtful; the manifestos read as a mix of satire, invitation, and myth. Yet they catalyzed real networks of seekers. This shows how the idea of a secret religious order can build movements even without a tightly organized group.

-

White Lotus in China: While not a single organization, White Lotus associations blended Buddhist devotion, millenarian prophecy, and mutual aid. Imperial crackdowns—especially after the late 18th-century rebellion—pushed adherents into clandestine cells. Their secrecy was born of political necessity, a dynamic with parallels in other regions where religious dissent and social protest intertwine.

These episodes show a spectrum: from underground survival to mythic projection. Inquisitions and wars of religion did not merely extinguish heresy; they stimulated innovation in religious organization, with secrecy both imposed and embraced.

Comparative Anatomy of Secret Societies with Religious Cores

Certain features recur when religious groups go secret. Understanding them makes it easier to compare cases without flattening their differences.

- Space: Hidden rooms, caves, cellars, and domestic altars. Mithraea mimic caves; Kakure Kirishitan put a cross behind a sliding panel. Alpine Waldensians used isolated barns and ravines.

- Time: Nocturnal gatherings or dawn rituals reduce visibility. Roman accusations against Bacchanalia targeted night meetings. Enslaved people in the Americas held hush harbors—nighttime worship deep in the woods.

- Initiation and codes: Grades, oaths, and passwords build trust. Mithraism formalized ranks; Pythagoreans used hand signs; later fraternities adapted similar mechanics. In persecuted settings, codewords distinguish friend from foe.

- Portable liturgy: When texts are risky, memory and song carry ritual forward. Hidden Christians in Japan held orasho; conversos preserved blessings as family sayings.

- Adaptive symbolism: Images with double meanings protect believers. Maria Kannon exemplifies this; so do fish and anchor motifs on Christian funerary art in Rome.

A healthy comparison notes not just what is shared but what is specific: a Roman soldier in a mithraeum and a Japanese farmer in a hidden chapel share secrecy, not theology or social position.

Communication: Codes, Songs, and Everyday Artifacts

When detection is dangerous, communication systems become art forms.

-

Symbols and acrostics: The ichthys fish compressed an entire confession into five Greek letters. Early Christians also used the anchor and the Good Shepherd as visual cues. In Jewish liturgy, acrostic techniques embedded author names or prayers in a way that could pass as poetic flourish.

-

Prayer as sound-shape: Orasho preserved Latin and Portuguese prayer forms phonetically across centuries, rendering sacred syllables into Japanese soundscapes. This shows how rhythm and cadence can carry meaning even when comprehension is partial.

-

Everyday objects as reliquaries: A rice scoop engraved with a tiny cross, a rosary hidden inside a hollowed-out walking stick, a candle lit behind a shutter at dusk—artifact and act blur. Archaeologists and ethnographers find these objects in attics and under floorboards; their wear tells stories of repeated, careful use.

-

Double-coded songs: In the antebellum United States, spirituals like Steal Away and Wade in the Water carried layered messages. The songs were explicitly devotional, yet they also signaled routes, timetables, and resolve for escape. While not a secret religion in the strict sense, this is an example of sacred culture enabling clandestine communication.

-

Theological permission for concealment: In Shia Islam, taqiyya developed as a doctrine permitting believers to hide their faith under mortal threat. This is not deception for advantage but a survival ethic, shaped by centuries as a minority under sometimes hostile rule. Similar reasoning appears in other traditions where martyrdom is honored yet not demanded in every case.

Codes thrive at the border of the ordinary. A secret group thrives when its members can make a greeting, a lyric, or a utensil carry sacred meaning without betraying them to outsiders.

Myths, Moral Panics, and the Peril of Secrecy

Secrecy invites projection. Authorities and bystanders fill gaps with fear or fantasy.

-

Roman fears of Dionysian excess led to the Senate’s sweeping claims about criminality in 186 BCE. Later, with the Templars, accusations of obscene kisses and idol worship likely reflected political agendas more than actual rites.

-

In early 17th-century Europe, the Rosicrucian furore showed how pamphlets can conjure an invisible brotherhood that people then claim to see everywhere. The trope of the hidden cabal becomes self-reinforcing.

-

The 19th-century Anti-Masonic movement in the United States emerged after the disappearance of William Morgan in 1826, who threatened to publish Masonic secrets. A real local scandal ballooned into a national fear that secret oaths undermined republican virtue. A political party formed and even ran presidential candidates. The episode demonstrates how a fraternity with religious symbolism but secular goals became a stand-in for anxieties about modernity.

-

More recently, conspiracy-minded panics have accused minority religious or spiritual groups of monstrous crimes without evidence. Such episodes remind us that secrecy can be an ethical minefield: it shelters the vulnerable, yes, but it also makes communities easier to slander.

A practical takeaway: the less the public knows, the more they imagine. Secret groups must balance their internal needs with the external cost of misunderstanding, and observers must cultivate evidence-based skepticism.

How Historians Study the Secretive

Studying the hidden requires a toolkit that accepts partial evidence and works to correct biases. If you want to do a careful reading of history’s clandestine communities, here is a step-by-step approach used by researchers and advanced by curious readers:

-

Start with the material. Excavated mithraea, for instance, are consistent in size and form across regions; the iconography of tauroctony scenes suggests a ritual logic even when texts are sparse. In Japan, household shrines with dual-use iconography confirm the existence of hidden Christian practice independently of hostile reports.

-

Read hostile sources critically. Inquisitorial files, court records, and polemical tracts often provide the richest details, but they were composed to convict or discredit. To handle them:

- Cross-check names and events with non-judicial records.

- Separate formulaic charges from specific observations. If every accused person is said to blaspheme the cross in identical language, you may be seeing a template rather than an event.

- Note what is implausible or mirrors stock accusations across centuries.

-

Value oral history, but test it. Communities pass down survival tales and ritual memories. Compare independent tellings, look for consistency in core elements, and respect the limits of living memory. For Hidden Christians, 19th-century visitors recorded orasho that can be traced to earlier liturgies.

-

Trace networks. Who knew whom? Where did ideas flow? For Rosicrucian enthusiasts, track printers, correspondents, and meeting places to see how an imagined brotherhood yielded real circles of exchange.

-

Look for domestication of ritual. When a faith goes underground, ritual often moves into kitchens, storerooms, or secluded outdoor spots. The clues are adaptation and miniaturization: a sacrament performed with crumbs and a sip instead of a chalice and loaf, an altar that folds into a cupboard.

-

Use comparative caution. Patterns can illuminate, but resist turning them into one-size-fits-all explanations. A mithraeum’s closed circle does not mean every secret rite is militarized; a clandestine prayer circle does not make a conspiracy.

These methods keep the story anchored in evidence while honoring the creativity of communities that survived by being hard to pin down.

Lessons for the Present

The history of secret religious groups offers practical lessons that travel well into our century.

-

Protecting minority faiths strengthens the civic fabric. When the law assures freedom of worship, there is less incentive for groups to retreat into total secrecy. Historical crackdowns—from Roman senatorial decrees to early modern inquisitions—tended to breed more suspicion and complexity rather than tidy uniformity.

-

Secrecy can be a healing discipline, not just a defensive tactic. Communities use private rituals to nurture identity, especially diasporas and refugees. The key is to distinguish privacy from isolation: some inwardness protects meaning without breeding misunderstanding.

-

Evaluate claims with a historian’s toolkit. When you encounter sensational accusations about hidden religious cabals, ask: who benefits from this story? What are the sources? Are there independent material traces? The discipline of skepticism is a civic virtue.

-

Learn from adaptive resilience. If you or your community preserves a fragile tradition, consider how history’s survivors did it:

- Prioritize portable practices—songs, prayers, and ethical habits that do not depend on large institutions.

- Maintain multi-layered symbols that can be read safely in different contexts.

- Create trust through mentorship rather than through labyrinthine hierarchies that can collapse under pressure.

-

In the digital age, secrecy has new tools and pitfalls. Encryption can protect community communication much as coded prayers did, but secrecy also makes communities vulnerable to conspiracy theories. Transparent boundaries—open statements of purpose, closed ritual details—can balance safety with public understanding.

The ethical thread that runs through all of this is simple: secrecy is most life-giving when it shelters integrity and community, not when it hides harm. History offers both the best and worst examples; we can choose which to emulate.

Further Reading and Resources

If this topic intrigues you, these accessible books and resources provide well-researched entry points:

- The Eleusinian Mysteries: Kevin Clinton’s studies and Michael Cosmopoulos’s work on the sanctuary’s archaeology.

- Mithraism: Roger Beck’s The Religion of the Mithras Cult and Manfred Clauss’s The Roman Cult of Mithras.

- Crypto-Judaism and Moriscos: Renée Levine Melammed’s studies on conversas in Iberia; Henry Kamen on the Inquisition’s social history.

- Hidden Christians of Japan: Stephen Turnbull’s works on Kakure Kirishitan and the global history of Christian missions in Japan.

- Nizari Ismailis: Farhad Daftary’s The Assassin Legends and The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines.

- White Lotus: Susan Naquin’s Millenarian Rebellion in China for a deep dive into late imperial contexts.

- Esotericism more broadly: Wouter Hanegraaff’s overview of Western esoteric currents.

Museums and archives often hold small but evocative exhibits: Roman mithraea reconstructed in European museums, regional collections in Spain and Portugal with Inquisition records, and community museums in Nagasaki that display Maria Kannon statues and household shrines. If you visit, look for the miniature: a worn rosary, an icon that could pass as something else, a prayer handwritten in a child’s school notebook. Those are the fingerprints of survival.

As you explore, carry two sentiments with you: empathy for those who kept a flame alive when wind and rain tried to extinguish it, and curiosity tempered by care for evidence. The rise of secret religious groups is not a side story of history—it is a recurring pattern by which communities endure, transform, and, when the time is right, step back into the daylight.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts