Why Did Baroque Music Leave A Lasting Mark

14 min read Explore the enduring influence of Baroque music, uncovering its innovative elements and cultural impact on classical and modern music traditions. (0 Reviews)

Why Did Baroque Music Leave A Lasting Mark?

From bustling Italian courts to majestic northern cathedrals, the swooping drama of Baroque music has captivated listeners for centuries. But what exactly set this era apart – and how did its sound sculpt the very foundations of Western music as we know it today? Let’s journey through the hallways of history and harmony to uncover why Baroque music’s influence has echoed far beyond its time.

The Birth of the Baroque Revolution

In late 16th-century Europe, the musical landscape was poised for transformation. The Renaissance period had blessed audiences with intricate polyphony, but composers hungered for something different – more drama, emotion, and immediacy. Enter the Baroque age, roughly spanning 1600 to 1750, erupting with change and innovation.

Key Italian cities like Florence became hotbeds of experimentation. Composers such as Claudio Monteverdi broke from tradition— most notably with his opera L’Orfeo (1607), often cited as the first great opera. This ushered in a fresh appetite for emotional storytelling and expressive depth.

Baroque didn’t just appear in music; it was part of a grander artistic current that flourished in architecture, painting, and sculpture. Just as ornate churches mesmerized worshipers with gilded altars, composers sought to wow listeners with new textures and tonal spectacles. The era’s bustling creativity invented forms and conventions that would chart the Western musical course for centuries to come.

Ornamentation and Virtuosity: Sound as Spectacle

Perhaps the most obvious Baroque hallmark is its extravagant ornamentation. This was not music intended as mere pleasant background; it was art that seized attention. Composers embedded expressive trills, rapid scales, and complex arpeggios, challenging musicians’ technical prowess. Audiences expected to be dazzled by performers such as violinist-composer Arcangelo Corelli or flutist Johann Joachim Quantz.

This showmanship wasn’t just for show. Virtuosity and ornamentation made music a living, dynamic event. Artists often improvised embellishments, turning each performance into a unique affair. Much like a baroque cathedral’s intricate facade, the lush details distinguished each piece, imbuing it with individuality.

Example: Listen to the violin part in Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. Each concerto brims with musical ‘decoration,’ from shimmering tremolos mimicking rainfall to rapid-fire passages signifying storms. These flourishes invigorated music-making with theatrical energy, a dramatic approach that shaped solo instrumental writing well into the Classical and Romantic periods.

New Musical Forms That Shaped History

Baroque composers didn’t just amplify expression—they engineered new blueprints for music itself. Many of the structures born in this era became foundational pillars. Here are a few game-changing innovations:

The Concerto

Vivaldi championed the concerto: a work spotlighting contrasts between a soloist (or a group, in a “concerto grosso”) and the ensemble. The form’s alternating loud and soft passages, dramatic tension, and interplay proved irresistible. Even today, the solo concerto — think piano or violin with orchestra — is a staple of concert repertoire.

The Fugue

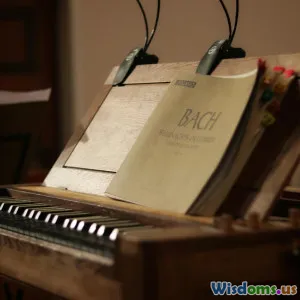

Johann Sebastian Bach perfected the fugue, where a single theme is echoed and layered by different instruments or voices. The intricate counterpoint in Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier and The Art of Fugue foreshadowed the complexity found in later symphonies and influenced composers from Mozart to Shostakovich.

Opera

Operatic storytelling—music and drama intertwined—matured during the Baroque. Monteverdi's innovations, implemented later by George Frideric Handel in his nearly 40 operas, demonstrated how music could express characters’ psychological depth. Opera’s model of recitative, aria, and chorus still underpins modern musical theater and film scores.

The Oratorio

During periods when opera performance was restricted (such as Lent), composers like Handel pivoted to oratorios—sacred, often biblical dramas performed without staging. Messiah (1742) stands as the archetype, uniting grand choral forces, soloists, and orchestra in a stirring narrative.

These forms didn’t remain confined to the Baroque. They provided launching pads that shaped everything from Beethoven’s piano sonatas to Hollywood film scores.

Harmony and the Birth of Modern Tonality

Baroque music witnessed the solidification of tonality — the system of organizing music around a central pitch or “tonic.” Before, modal styles dominated Renaissance sounds. Baroque composers constructed musical architectures woven from major and minor chords, tension, and resolution.

Johann Sebastian Bach’s chorale harmonizations and Pachelbel’s Canon in D serve as iconic examples. The sense of “home” and “destination” in these pieces — resolving from dissonance to consonance —was baked into the DNA of virtually all Western classical, pop, and jazz music that followed.

This was more than a theoretical shift. The clarity and structure that tonal harmony provided made music broadly accessible and deeply moving. Audiences could feel the push and pull of expectation and fulfillment, much like a storyteller builds and releases suspense.

Democratizing Music: Accessibility and Broad Appeal

Another reason Baroque music left such a deep legacy is its spread beyond the privileged elite. Thanks to the emergence of printed music and a vibrant public concert culture — especially in centers like London and Leipzig — music became easier to publish, share, and learn. Composers like Handel made fortunes by premiering new oratorios to crowds of eager ticket-holders.

Instrumental advancements also improved access. The violin family (over predecessors like the viola da gamba) gave aspiring musicians approachable, portable options, and developments in keyboard instruments brought music into middle-class homes for the first time.

Fact: By the early 18th century, amateur orchestras and choir societies had blossomed in cities across Germany, England, and the Netherlands. The ability for non-professionals to participate in complex musical works marked a profound democratization — one that would swell further with the explosion of symphonies and community ensembles in the Classical era.

Crossroads of Science, Faith, and Reason

The Baroque era mirrored its age, pressed between medieval faith and Enlightenment reason. Music was seen as a blend of scientific order and spiritual expression.

In churches, J.S. Bach’s sacred cantatas illustrated not only Lutheran theology but also mathematical sophistication. Bach’s near obsession with symmetry, symbolism, and structure found common ground with the era’s great thinkers—such as Isaac Newton’s explorations of law and order.

Meanwhile, secular Baroque music complemented the intellectual ferment of the time. The structure and balance of Baroque compositions echoed the burgeoning confidence in human reason and discovery, blurring boundaries between sacred and worldly, the rational and the sublime.

Global Impact: Blending Traditions Across Continents

Baroque music didn’t stay within European borders — its adaptability and appeal ensured a global reach. Missionaries and colonists carried the music to the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Local traditions merged with Baroque conventions:

- In colonial Latin America, Spanish and Portuguese settlers brought European music that soon blended with indigenous rhythms and melodies, as seen in Mexican Baroque choral works or Peruvian "villancicos."

- The first known published music in North America, The Bay Psalm Book (1640), reflected Puritan influences from England.

- In South India, Jesuit missionaries introduced Western harmony into Carnatic music, leading to hybrid hymn traditions still sung today.

Today, elements of Baroque thinking and sound—especially the clear-cut use of chords and expressive melody—are embedded in global gospel, folk, and popular musical idioms.

Lasting Lessons: Adaptability, Emotion, and Craft

So why does Baroque music endure? At its core are principles still valued by creators and educators across genres:

- Adaptability: The notion of improvisation and interpretation remains fundamental to jazz, rock, and even contemporary classical music. Baroque outlines allow for personal imprint—a concept only growing in importance in a digital, DIY age.

- Emotional Directness: The focus on stirring hearts has set a precedent: from Beethoven’s stormy sonatas to movie soundtracks that swell and fade with the onscreen mood.

- Technical Mastery: Learning Bach fugues or Corelli sonatas remains a time-honored path for honing skills—a musical "boot camp" for the world’s aspiring maestros.

Rediscovery in the Modern Age

For centuries, Baroque music was overshadowed by subsequent Classical and Romantic titans. Yet, the 20th-century historical performance movement reignited passion for the era’s authentic sound. Pioneers like Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Gustav Leonhardt uncovered original manuscripts and ancient playing techniques, revitalizing global interest in period-accurate performances.

Suddenly, crisp violins and glowing harpsichords filled modern halls, radio, and cinema — think the use of Vivaldi and Purcell in movies from Master and Commander to The Favourite. This resurgence highlighted just how fresh and captivating Baroque music remains, centuries after its heyday.

The Baroque Legacy: A Living Tradition

More than just a chapter in history books, Baroque music is a living, breathing tradition. It’s studied, performed, reinvented – and above all, loved – by millions. Its directness, richness, and innovative spirit continue to inspire composers, performers, and listeners around the world.

The next time a violin soars in dramatic dialogue with an orchestra, or a choir’s harmonies curl through a cathedral nave, remember: the indelible mark of Baroque music remains, an eternal part of our shared artistic heritage.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts