Why Did Medieval Societies Fear Street Illusionists

17 min read Explore the social and cultural fears surrounding street illusionists in medieval societies and their alleged impact on public belief. (0 Reviews)

Why Did Medieval Societies Fear Street Illusionists?

The winding alleys of medieval towns echoed with the footsteps of not just merchants and monks, but traveling performers armed with nimble fingers, clever tongues, and a seemingly supernatural command over the senses. Among them, street illusionists occupied a particularly puzzling—and perilous—place in the popular imagination. Their acts bewildered, delighted, and, in ways both energizing and disturbing, unsettled their contemporaries. Exploring why medieval societies feared these sleight-of-hand artists uncovers a turbulent intersection of faith, superstition, power, and the limits of perception.

The Medieval Context: Understanding the Age of Wonders

Medieval Europe (roughly the 5th to 15th centuries) was a world brimming with faith—in Christianity, celestial order, and the pervasive sense that everything occurred via divine or demonic means. Wonders, real or fabricated, punctuated everyday existence. When crops failed it might be the "evil eye"; sudden cures were miracles or witchcraft. Performers who seemingly bent the rules of the world with illusions inevitably found themselves at the pivot of admiration and suspicion.

Urban spaces—bustling markets, town squares, and fairgrounds—provided ideal stages for street magicians. Notable records from across France, Italy, and England document performances involving cups-and-balls routines, vanishing objects, or even simple sleights that made coins "disappear" in full view of audiences. Jean Gerson, a prominent 15th-century French theologian, lamented that townsfolk devoted prayers to God and his saints but imported supernatural acts into their daily lives by constantly seeking "charmes and juggling." Clearly, illusions had pierced the very heart of everyday faith, which brought both fascination and fear.

Illusion or Witchcraft? The Blurred Lines

Illusionists were not merely colorful street performers—they skirted a razor's edge between harmless spectacle and grave accusations. Medieval society had fuzzy boundaries between trickery and the supernatural, making it perilous to dabble in magic, no matter how innocent.

Consider the fearsome consequences faced by practitioners accused of sorcery.

-

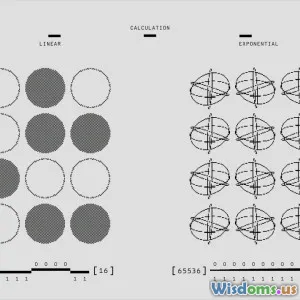

The Witchcraft Panic: Popular fear peaked during episodes later termed the “witch craze,” especially from the late medieval period onward. Manuals like the infamous Malleus Maleficarum (1487) provided systematic methods for interrogating sorcerers and magicians, blurring the difference between magicians and street illusionists. Even basic acts—such as making objects float or disappear—could be construed as dealings with the devil.

-

Medieval Law and Doctrine: The Church’s condemnation of “jugglers” and “conjurers” was explicitly stated. The Fourth Lateran Council (1215), for instance, categorized certain magic as a heresy. Illusionists, whose performances could not be readily explained, were routinely suspected of invoking forbidden powers. Old English law books advised bishops and sheriffs to police public spaces for ominous entertainers lest they corrupt the souls of onlookers.

-

Example: The Misfortune of the Magician Roland: Chronicles from Cologne relate how the illusionist known as Roland was detained after a performance. The crowd, unable to separate dexterity from diabolism, testified that his sleights were achieved “with the help of wicked spirits.”

These suspicions rendered the practice of performance magic dangerous—not simply a curiosity but a possible death sentence.

Conflicts with Faith: The Church’s View of Deception

In deeply religious society, the structure of ritual, miracle, and mystery belonged to the Church. Anything that threatened to mimic or compete with those powers was inherently fraught with risk.

Miracle vs. Magic:

Medieval belief emphasized that wonders must come from God or His saints. Illusions eroded this clarity: a conjurer producing fire from nothing or seemingly teleporting objects appeared to duplicate Biblical miracles. What the public saw as entertainment, theologians interpreted as spiritual threats—interventions not only mysterious, but potentially blasphemous or heretical.

-

St. Thomas Aquinas’ Caution: Writing in the 13th century, the influential theologian strongly denounced uses of "prestidigitation" and magical effect, unless openly proven as tricks or sleight-of-hand—not real sorcery. Yet, for the average parishioner unable to discern method from miracle, the performances were alarmingly ambiguous.

-

Public Penitence and Penance Manuals: The Penitential of Theodore—one of the early Church disciplinary texts—lists penances for attendance at magical shows; those who watched were told to fast for three years, on suspicion of dabbling in forbidden spectacle.

-

Sermons and Stereotypes: Street illusionists (or "jugglers") often featured in sermons as symbols of folly or agents of deception, sometimes even accused—without proof—of pacts with the devil. The French preacher Stephen of Bourbon denounced them as "antichrists" because they entertained at festivals dedicated to the saints, muddying sacred with profane.

The Power of Perception and the Threat of Uncertainty

Street illusionists wielded not just misdirection or trick props, but an even softer power: doubt. In a culture striving for clear divisions between true and false, the ambiguous spectacle of a magic square or conjured handkerchief probed cracks in conventional wisdom.

Disrupting Social Certainty:

Medieval authority—both secular and ecclesiastical—rested on clear, untouchable truths. Illusionists threw these into flux by:

- Performing acts that even learned viewers could not explain with appeals to faith or reason.

- Playing upon the credulity of the crowd, challenging social hierarchies: if a lowly performer could seem divine, could a priest or knight be less special?

- Sowing narratives about the limitations of ordinary human senses, ultimately nurturing doubt about visible reality—a threat to the entire structure of medieval knowledge.

Fear as Social Glue:

Suspicion consolidated communities: shared anxieties about performers promoted collective vigilance and gossip, which could escalate quickly from caution to mob violence. Punishing the illusionist became a way to purify the group, reasserting the dividing line between order and chaos.

The Association with Outsiders and Social Margins

Illusionists, like much of Europe's traveling underclass—"gypsies," minstrels, itinerant healers—existed at society’s unstable edge. Their foreign dress, strange languages, and rootless existence bred wariness and stigma.

Marked as Other:

- Official documents repeatedly link jugglers and conjurers to outsiders: in England, statutes barred non-local entertainers from town markets, on suspicion of fraud or sorcery;

- Bands of traveling magicians might be suspected not only of magic, but also of theft, espionage, or incitement to disorder;

- “The magician is a stranger,” observed a municipal ordinance from late medieval Venice, “and to him we owe no trust.”

Folklore Evidence:

- The Gesta Romanorum, a collection of moralizing tales, warns of “wandering Saracens” whose conjuring tricks fool pious villagers’s.

- Broadside ballads popular in English markets featured Jewish or Moorish magicians as menacing disruptors—using the fear of the unknown performer as a shorthand for general fear of foreigners.

This fusion of xenophobia, class oppression, and religious anxiety rendered even the most innocent illusionist into a figure that embodied multiple dangers, all at once.

Economic Threat: Distracting, Swindling, or Corrupting the Laboring Class

Beyond metaphysics and faith, practical concerns loomed large. Town officials and guilds policed their ranks fiercely, already pressed by vagabonds and petty criminals.

Disrupting the Marketplace: Street illusionists lured crowds, causing traffic snarls, pickpocketing, and an “idle” detour for laborers.

- In 1389, the Paris city ordinances banned “those who draw crowds away from honest trade with feats and silly tricks, confounding the city’s business.”

- Shopkeepers and craftspeople resented both the competition and the threat of theft: audience patches provided lucrative opportunity not only for magicians but also cutpurses and confidence tricksters.

Swindling and Dishonesty:

Illusionist acts frequently intertwined with gambling, fake cures, or confidence scams. The classic shell game, still notorious centuries later, packed an artful demonstration of sleight-of-hand with an unlawful contest, fleecing the naive.

- Will of Oswald de Etone (England, 1321), for example, recorded losses incurred in “playing at the table with the doer of marvels,” a tacit admittance that their tricks cost real money.

- Such exposures conditioned officials and churchmen alike to conflate entertainment with crime.

Through a practical lens, a street magician threatened not just the mind but the material order—another justification for suspicion and eventual suppression.

Case Studies: When Illusionists Became Legends or Victims

Throughout Europe, records shine rare light upon specific cases illustrating the double-edged fate of street conjurers:

- The Death of "John the Conjuror": In York, 1434, court rolls recall a juggler executed "for his deviltries," following a botched escape act during the Corpus Christi fair.

- The Enigmatic Fame of Jacques the Miraculous: Banned from Lyon for inciting unrest after an illusion involving a "headless child," Jacques nonetheless found his legend retold as both a martyr to curiosity and a danger to the faith.

- Misleading Nobility: Chronicler Matthew Paris recounts how “a Saracen magician” duped the Earl of Salisbury’s household, losing no small sum of silver, and prompted authorities to intensify regulation of street entertainers.

These stories both amplified fear—circulating as cautionary tales—and etched the magician deeper into folklore. Whether as heroes or scapegoats, street illusionists became symbols of social tension.

Surviving the Climate of Fear: Strategies of Medieval Illusionists

While many suffered persecution, some ingenious street magicians navigated the risks of medieval suspicion. Their survival strategies provide a fascinating glimpse into adaptive performance art:

Demystifying the Act: To allay fear, some illusionists openly explained their tricks, emphasizing harmlessness. Manuals such as Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584, a rare early description) stressed natural explanations and denounced fraudulent sorcery—even providing step-by-step instructions for card tricks and simple illusions to disarm suspicion.

Patronage and Social Shielding: Not every court rejected the magician. Skilled performers occasionally found powerful backers for whom their acts were novel amusements or secretarial skills (such as cryptography or codewriting). Protection from nobility often allowed them to operate just on the edge of acceptability.

Integration with Safe Traditions: Clever magicians embedded their acts within accepted cultural rituals: harvest festivals, morality plays, or mummer’s parades. By cloaking acts of wonder inside community-sanctioned events, they lessened suspicion. Tricks masquerading as religious allegories or lessons (“turning water to wine” as a Lenten parable) were more palatable.

Going Underground, Literally and Figuratively: For those denied civic acceptance, the underground circuit beckoned. Secret shows in inns, tenements, or remote villages provided entertainment secluded from official view—albeit with greater risk.

Legacy and Lessons: The Enduring Power of the Street Magician

The medieval fear of street illusionists may seem foreign, even archaic, but echoes resonate today. The prospect that reality can be manipulated before one’s eyes continues to enthrall and unsettle. Even now, stage magicians sometimes court controversy amid claims of genuine psychic ability, and performers tread the fine line between entertainment and suspicion.

By dissecting the roots of medieval suspicion—religious strictures, economic anxieties, xenophobia, and the threatened certainties of knowledge—we glimpse a world in which the boundary between the possible and the impossible was far thinner than it appears today.

For hundreds of years, street illusionists remained catalysts in the alchemy of wonder and terror, proof that a society’s deepest values emerge most clearly when they are challenged, subverted, and, occasionally, spectacularly fooled. Their legacy endures wherever a conjuror draws a crowd and shuffles reality—momentarily—before our very eyes.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in history of magic

Popular Posts