Advice From Experts Persuading the Brain Through Illusion

37 min read Expert-backed techniques using illusions to guide attention, shape perception, and improve decision-making—blending neuroscience, psychology, and ethical design for marketing, education, and UX. (0 Reviews)

We are all professional illusionists, whether we know it or not. A teacher staging a surprising demonstration, a product manager orchestrating a “lightning-fast” app, a marketer crafting a price comparison—all deploy illusions. Not tricks in the cynical sense, but guided experiences that nudge the brain to construct a reality that serves a useful end. The brain is a prediction engine and an energy miser; it loves shortcuts. Persuasion through illusion harnesses those shortcuts—carefully—to help people see, feel, and choose with less friction and more clarity.

In this article, we’ll dig into expert advice on how illusions work, where they go wrong, and how to use them ethically. You’ll find practical playbooks, research-backed examples, diagnostics for testing whether an illusion actually persuades, and guardrails so that “influence” doesn’t slide into manipulation. Think of it as a toolkit for sculpting experience from the brain outward.

The Brain Is a Prediction Machine: Why Illusions Work

Perception is not a photograph; it’s a negotiation. The dominant view in cognitive neuroscience—predictive processing—holds that the brain constantly generates hypotheses about the world and updates them with incoming sensory signals. In Bayesian terms: prior expectations meet likelihoods to produce a posterior belief (your current perception). Illusions exploit this meeting point by steering priors or shaping the likelihoods.

Key idea: the brain cares more about being fast-and-useful than perfectly accurate. As a result, it takes these shortcuts:

- Stability via priors: We assume light comes from above, faces are convex, and shadows darken objects rather than change their color. The famous checker shadow illusion (Edward Adelson) works by tapping color constancy and lighting priors—two squares identical in luminance look different because the brain “corrects” for a shadow that it believes is there.

- Context over absolute values: Perception emphasizes edges and contrasts, not raw intensities. That’s why a piece of text becomes more legible with strong contrast rather than merely brighter pixels.

- Efficiency in attention: The brain spotlights what seems behaviorally relevant. If you’re counting basketball passes, a gorilla can waltz through the scene and you won’t notice (Simons and Chabris, 1999). The brain filters what doesn’t fit your current goal.

Practical takeaway: To persuade through illusion, decide whether you’re shaping priors (expectations) or the likelihood (sensory layout). Setting expectations—like a price anchor—changes what people are ready to see. Shaping the layout—like a progress bar that “leaps” at key moments—alters the sensory evidence the brain weighs most heavily.

Classic Perceptual Illusions and the Messages They Carry

A lightning tour of optical illusions shows the rulebook the brain uses and how you can apply it.

- Müller-Lyer illusion: Arrows that end in inward or outward fins change how long a line appears, even when lines are identical. Lesson: Contextual cues (corners, depth) bias metric judgments. Application: Present product dimensions with a reference frame that supports the perception you want (e.g., a compact suitcase rendered in a tight, legible frame so it “reads” as small).

- Ponzo illusion: Converging lines (like railroad tracks) make identical objects look different in size because the brain infers depth. Application: To emphasize importance or scale in visuals, place an object in a “converging” layout that implies greater distance; the object will appear larger and more prominent.

- Ebbinghaus illusion: A circle appears larger when surrounded by small circles and smaller when surrounded by large circles. Application: Price perception and portion sizes in food service are subject to this; a moderate portion on a smaller plate feels generous and satisfying.

- Kanizsa triangle: The brain “fills in” contours that aren’t actually present. Application: Suggestive design can imply structure without drawing every line—useful in logos, icons, and diagrams that feel complete with fewer elements.

- Shepard tables: Two tabletops of equal area appear drastically different in shape due to three-dimensional interpretation. Application: Be cautious with shape comparisons in dashboards; always provide numeric labels to counter misinference.

- Checker shadow (Adelson): Local brightness comparisons lead to persistent misperceptions of color under inferred lighting. Application: In product photography, control shadows and backgrounds; otherwise, identical colors can be perceived as mismatched in quality.

Bonus insight from sports: Perceptual illusions correlate with performance. Studies have found that athletes who perceive targets (like a baseball) as larger often perform better in that moment. Perception and action are a loop; making a goal look attainable can make it more attainable. For persuasion, this means visually simplifying complex tasks—chunking a multi-step form—can make completion feel easier and thus be more likely to occur.

Attention as a Spotlight: Misdirection from Magic to UX

Magicians are master interaction designers. They shape attention and timing so that the audience’s mental model never sees the crucial move.

- Inattentional blindness: The gorilla experiment shows we can miss the obvious if our attention is occupied. In practice, this means that if you want users to notice a key call to action (CTA), create a goal context first (e.g., “Get your personalized estimate”), then provide the CTA as the natural next step.

- Change blindness: In Simons and Levin’s door experiment, people failed to notice the person they were talking to had changed mid-conversation. For product changes, do not assume users notice new features; highlight them with staged tours and temporary visual accents.

- Gaze and gesture cues: Magicians use gaze direction and open hand gestures to guide attention. In interfaces, human or mascot faces that “look” toward an element can nudge users’ attention. Eye gaze in marketing imagery can measurably increase click-through on adjacent text.

- Time misdirection: The crucial action often happens after spectators believe the trick is “over.” In flows, place necessary but dull steps after a rewarding micro-victory. For instance, celebrate account creation and then collect optional profile details; completion rates rise because the moment of friction is post-reward.

Practical design patterns that leverage attention illusions:

- Skeleton screens and shimmer: Showing a structured placeholder immediately reduces perceived wait time. The user’s attention is occupied by a preview, and the brain infers progress.

- Staggered reveal: Present content in digestible chunks with deliberate whitespace. The brain prefers predictable rhythm; it reduces cognitive load and speeds scanning.

- Contrast choreography: Use one element with high salience (size, color, motion) at a time. Multiple competing highlights nullify each other and degrade persuasion.

Language Illusions: Framing, Anchors, and the Shape of Choice

Words shape priors. When Kahneman and Tversky presented the Asian disease problem, people preferred different policies depending on whether outcomes were framed as “lives saved” or “lives lost,” even though the probabilities were identical. The verbal frame creates a value landscape the brain navigates.

- Anchoring (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974): An initial number—arbitrary or informed—pulls subsequent judgments toward it. A $1,200 “compare at” price makes $799 feel like a win. Ethical use: anchors should be plausible and supported by real reference classes.

- Decoy effect (Huber, Payne, and Puto, 1982): Introducing a dominated option makes another option more attractive. For instance, offering three subscription tiers where one is clearly inferior in price-to-value makes the “middle” plan look like the best deal. Use sparingly; transparent value comparisons build trust.

- Compromise effect: People gravitate toward the middle option when they fear extremes. To guide choice, place the option you want adopted as the rational center with clear reasons.

- Loss aversion: People weigh losses roughly twice as heavily as gains. Messaging that highlights “what you keep” by acting now (rather than “what you’ll gain”) can be more persuasive. Keep it accurate; avoid fear-mongering.

- Defaults and preselection: Choosing a default nudges adoption by removing friction. Given how sticky defaults are, use them only when they align with user welfare and expectations.

Template for ethically persuasive copy:

- Set context: Define the user’s objective first. “You’re here to protect your data.”

- Provide a reference: “Most professionals choose end-to-end encryption for sensitive files.”

- Offer a calibrated anchor: “Advanced security is $12/month; the basic plan is $8/month.”

- Position the compromise: “Standard includes encryption and backups for $10/month—best for most.”

- State the loss of inaction: “Without encryption, you risk exposure if your device is lost.”

Memory Is a Story We Keep Rewriting

Memory illusions reveal how suggestions and post-event information reshape recollection.

- Misinformation effect (Loftus): After witnessing an event, exposure to leading questions changes memory. Asking whether there was “a broken headlight” leads to more false reports than asking about “the headlight.”

- Illusion of explanatory depth (Rozenblit and Keil, 2002): People believe they understand complex systems (zipper, bicycle) better than they do; attempts to explain expose gaps. In persuasion, brief checks—“Explain how this feature works in your own words”—can recalibrate overconfidence and motivate learning.

- Source confusion: People remember the content but forget where it came from. Over time, disclaimers detach from claims. If you’re combating misinformation, repeated, clear, affirmative statements of truth outperform negations.

Practical safeguards:

- Use concrete timelines and snapshots: “Here’s how your security settings looked last Tuesday.” Time-stamped visuals tie memory to a stable reference.

- Provide retrieval cues: Tag notes or receipts with distinctive icons and keywords; these cues lower the effort to recall and reduce false reconstructions.

- Teach through generation: Have users generate part of the content (e.g., draw a diagram or fill in blanks). Generation effects make the memory more resilient to later distortion.

Multisensory Merging: Tricks of Sound, Touch, and Vision

Perception is multisensory. The brain integrates inputs based on reliability and timing, often trading accuracy for coherence.

- McGurk effect: Hearing “ba” while seeing lips articulate “ga” yields the fused experience “da.” This shows audiovisual integration is mandatory and constructive. In video content, ensure lip sync and audio clarity; otherwise, your message literally changes.

- Ventriloquism effect: A sound’s perceived location shifts toward a salient visual source. In augmented reality, aligning subtle visual indicators near an audio alert will make the sound “come from” the right spot, helping users orient quickly.

- Rubber hand illusion (Botvinick and Cohen, 1998): Synchronous stroking of a visible fake hand and a hidden real hand induces ownership of the fake limb. In haptics, timing is everything. Tactile feedback must land within tens of milliseconds of the visual event to feel “one.”

- Crossmodal correspondences: People map high pitch with lightness and sourness, low pitch with darkness and bitterness. Sonic seasoning can make a beverage taste crisper if paired with higher-frequency tones. Restaurants and brands use this to heighten product experience without changing ingredients.

Design opportunities:

- Onboarding with micro-haptics: A gentle vibration synchronized with a button expansion confirms success and reduces uncertainty.

- Audio branding: Pair a signature sound with a visual logo that pulses in synchrony. Over time, the song and symbol become one perceptual unit—faster recognition with less visual real estate.

- Taste and pitch pairings: For food-tech and CPG, test ambient soundtracks to subtly guide flavor expectations (sparkling, citrusy products with bright, staccato audio).

Time Illusions: How Waiting Feels Shorter or Longer

We never experience time directly; we estimate it based on change, attention, and expectations. Persuasion often hinges on whether a delay feels reasonable.

- Filled time feels shorter: Elevators use mirrors not merely for vanity but to occupy waiting attention. In apps, show a playful tip, a preview, or a skeleton screen. Empty waits feel longer and more frustrating.

- Progress bar dynamics: Nonlinear progress indicators that jump early (“front-loading”) create momentum. People infer that if the start was quick, the end is near—even if the total time is unchanged.

- Goal-gradient effect (Hull, 1932): Motivation increases as people feel closer to a goal. Stamp cards that start with two “free” stamps (out of 12) are completed more often than cards with zero (out of 10) even though effort is identical. Show partial completion from the start.

- Fairness and transparency: Queues feel shorter when they seem fair and when there’s visible order. Display position in line and estimated times with updates. Uncertain waits feel longer than known ones.

How-to for persuasive waits:

- Announce the play: “We’re configuring security (about 30 seconds).”

- Fill the frame: Show structure—steps 1–3 with live highlights. Avoid a single spinning icon without context.

- Front-load motion: Animate early increments quickly, then slow subtly while providing micro-rewards (tips, previews).

- Offer an opt-out: “We’ll email you when it’s ready.” Knowing there’s a choice eases impatience even if users don’t take it.

Ethical Persuasion: A Code of Conduct for Illusionists

Because illusions steer perception and choice, ethics are not optional.

- Beneficence: The intervention should plausibly improve the user’s outcomes—health, understanding, savings, safety—not merely company metrics.

- Autonomy: Users must retain meaningful choice. Defaults should be reversible. Avoid dark patterns like pre-checked boxes that obscure costs.

- Transparency: When possible, reveal the mechanism. “We show progress in steps to make the process clearer.” Humanizing the intent builds trust.

- Reversibility test: If this were used on you or someone you care about, would it feel fair? If not, don’t ship it.

- Inclusivity: Illusions can have differential effects. Test across age, culture, language, and neurodiversity. For example, susceptibility to the McGurk effect varies; don’t rely on a single sensory trick.

- Evidence over lore: Require empirical validation. If a nudge fails to improve comprehension or well-being, remove it—even if it boosts clicks.

How-To Playbook: Practical Scripts and Templates

Use this step-by-step system to design, test, and deploy persuasion through illusion.

- Define the behavioral goal and the user’s good

- Goal: What should the user do or understand? “Enroll in two-factor authentication.”

- Good: Why does this help them? “Reduces risk of account takeover.”

- Map the cognitive levers

- Expectation lever: What prior can we set? “Most professionals secure their accounts in under 2 minutes.”

- Sensory lever: What arrangement will highlight the next action? “Large, high-contrast button labeled ‘Secure my account’ with a short explanation.”

- Timing lever: Where can we deliver a micro-reward? “Confetti checkmark after activation; then optional device naming.”

- Select illusions by class

- Attention: Staged tour with spotlight overlay on the 2FA setting; fade background to limit distractions.

- Framing: “Protect what’s already yours” instead of “Add a new hassle.”

- Time: Progress indicator with three steps; early jump to 33% upon pressing “Begin.”

- Social proof: “87% of users in your industry use 2FA.” Ensure accuracy.

- Script the copy

- Context: “You’ve locked your door. Now lock your account.”

- Anchor: “Takes about 90 seconds.”

- Loss framing: “Without 2FA, a stolen password is enough. With 2FA, it’s not.”

- Commitment: “Send me the code” as the primary CTA.

- Build the experience

- Visuals: High-contrast, single focal point per screen. Skeleton loaders between steps.

- Multisensory cues: Soft confirmation chime and subtle haptic pulse when code is verified.

- Accessibility: Keyboard navigation, descriptive labels, captions for sounds.

- Pre-mortem and safeguards

- Ask: “How could this backfire?” If the wait exceeds 10 seconds, provide an email alternative.

- Ethics check: Are defaults reversible? Is data handling clear? Provide a one-click disable.

- Test and iterate (see Diagnostics section)

- Define success metrics beyond clicks: adoption, follow-through, comprehension, and long-term retention.

Templates for common scenarios:

-

Pricing page

- Use a three-tier layout with the target plan in the center, clearly superior on key dimensions. Provide an honest “compare at” value but avoid arbitrary strikethroughs.

- Present the monthly price larger than the yearly equivalent only if you also show total annual savings in exact numbers.

- Include a fairness cue: “Change or cancel anytime.”

-

Onboarding checklist

- Start with a visible 20% completion state (e.g., “Account created” pre-checked).

- Group tasks by cognitive similarity; users complete clusters faster when the brain can reuse context.

- Show expected time per task (30s, 1 min) to reduce uncertainty.

-

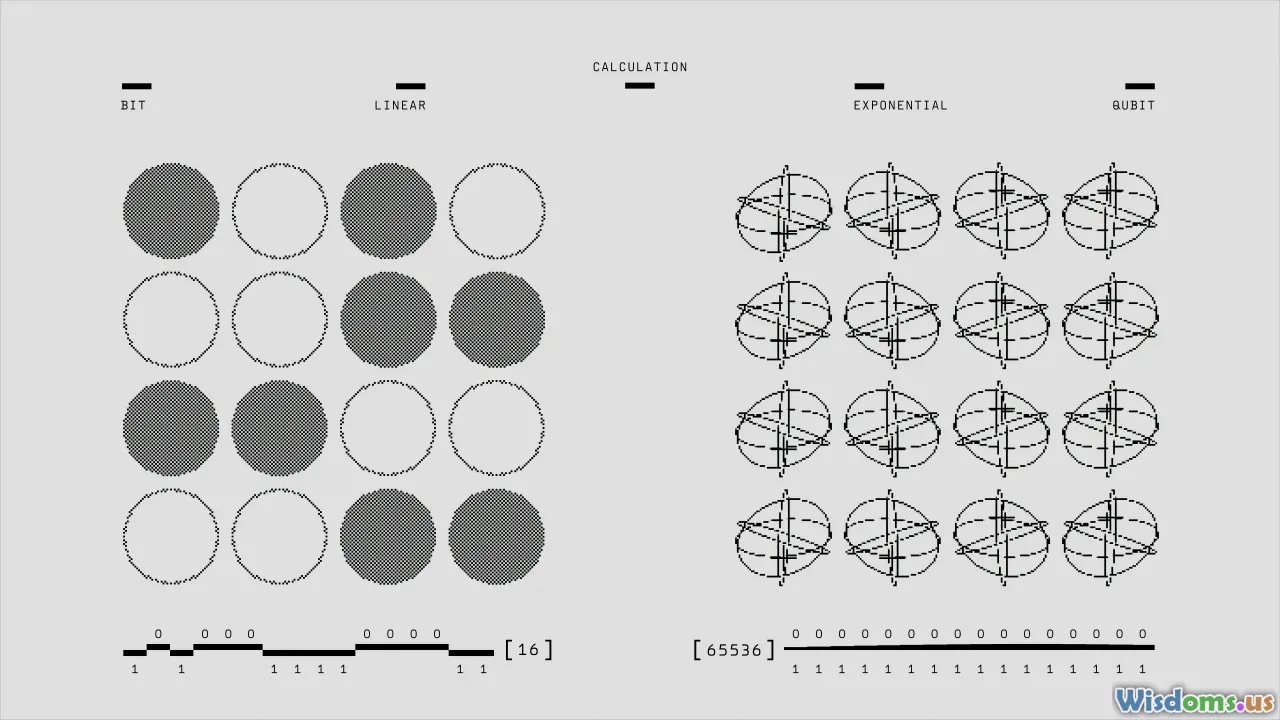

Educational content

- Begin with a prediction: “Before we explain, guess which graph shows exponential growth.” Then reveal. Generation solidifies learning.

- Use dual coding: simple visuals plus concise narration. Avoid text-heavy slides.

Diagnostics: Measuring Whether the Illusion Works

Illusions feel compelling, but feelings mislead. Validate with data and guard against self-deception.

- Randomized A/B tests: Split traffic, pre-register hypotheses, and define primary outcomes (e.g., 2FA activation). Report effect sizes and confidence intervals, not just p-values.

- Sequential testing: Use Bayesian methods or group-sequential designs to avoid peeking biases.

- Attention tracking: Heatmaps and eye-tracking reveal whether highlights are actually seen. If users ignore your marquee element, it isn’t persuasive.

- Comprehension checks: After exposure, ask one or two factual questions. If a framing increases clicks but reduces understanding, it’s a fail.

- Longitudinal follow-up: Persuasion should sustain behavior, not spike churn later. Check 30-, 60-, and 90-day retention and satisfaction.

- Fairness analysis: Segment results by demographic and accessibility needs. Look for disproportionate confusion or drop-off.

Practical experimental blueprint:

- Hypothesis: “Skeleton screens reduce perceived wait time and increase task continuation by 10%.”

- Metrics: Time to first drop-off, subjective wait rating (1–7), completion rate.

- Control: Static spinner with estimated time.

- Treatment: Structured skeleton with staged reveals and contextual tips.

- Sample size: Compute via power analysis to detect a 10% lift at 80% power.

Case Studies: Hospitals, Retail, and Remote Work

- Healthcare: Open-label placebos and transparent illusions

- Insight: Placebos can work even when patients know they are placebos, provided the rationale is credible and empathetic (Kaptchuk and colleagues). The “illusion” here is expectation harnessed ethically.

- Application: Pain management apps can frame relaxation training with honest language—“Many people feel relief through expectation and attention shifts”—and still produce meaningful benefits.

- Waiting rooms: Display live queue order and reasons for delays (“Emergency arrival prioritized”) to reduce perceived unfairness. Offer a checklist to complete during the wait; filled time feels shorter.

- Retail: Decoy and context in shelf design

- Insight: A dominated decoy (smaller, pricier) can make a target product more attractive. But long-term trust hinges on honesty.

- Application: Curate comparative cards showing attribute-by-attribute differences. Place related items in layouts that imply depth (Ponzo) so key SKUs pop. Use smaller plates or bowls for samples to increase perceived abundance.

- Pricing board: Anchor with a premium option that is legitimately premium (origin, quality, warranty). Highlight the middle option as the rational choice with explicit value statements, not vague superlatives.

- Remote work: Presence and tempo illusions

- Insight: Team cohesion can suffer without co-presence. Create the illusion of shared space with ambient indicators (soft soundscape, presence bubbles) and synchronized rituals.

- Application: In video meetings, use subtle audio chimes synchronized with visual hand-raises to create a sense of rhythm. For async tools, show “currently editing” avatars to reduce the need for pings. Progress trackers that jump early can motivate contributors to finish tasks.

When Illusions Fail: Cultural, Individual, and Context Boundaries

Illusions aren’t universal.

- Cultural variation: The Müller-Lyer illusion is stronger in “carpentered” environments with rectilinear architecture (Segall, Campbell, and Herskovits, 1966). Don’t assume a visual trick generalizes across markets.

- Neurodiversity and sensory weighting: Susceptibility to the McGurk effect and other multisensory fusions varies. Provide redundant cues (text + icon + sound) so no single channel is mandatory.

- Expertise dampens some illusions: A trained radiologist may see through certain perceptual traps in medical images. Similarly, experienced shoppers discount price anchors if they know the category’s baseline.

- Fatigue and stress: Under cognitive load, people rely more on heuristics. This can increase persuasion but also errors. Counterbalance by simplifying options and highlighting safety nets.

- Knowledge inoculation: Explaining how a specific illusion works can reduce its power (a good thing if you’re combating misinformation). If your persuasion depends on secrecy, that’s a red flag.

Risk mitigation checklist:

- Test in target segments and cultures.

- Provide alternative paths (skip, more info, choose later).

- Pair illusions with accuracy cues (numeric labels, footnotes, tooltips).

- Monitor for backfire: Does the intervention trigger reactance or distrust?

Building Micro-Illusions Into Products and Content

Think of illusions as micro-ingredients that flavor an experience. Use them sparingly and intentionally.

Patterns you can adopt today:

- Predictive prefetch + visual readiness: Preload likely next screens and display a “ready” state as the user arrives. The illusion is smoothness; the reality is smart scheduling.

- Implied causality: Sequence related animations so effect follows cause instantly—a toggle flips, the setting card locks, then a subtle sound plays. Correct timing convinces the brain that the system is responsive and reliable.

- Weight through physics: Interface elements with slight easing and inertia feel more “real.” People infer quality from consistent motion curves; this is why platform-specific motion guidelines matter.

- Guided triads in storytelling: Set expectation, violate it slightly, resolve. This cadence keeps attention without exhausting the audience and makes key points memorable.

- Scarcity with integrity: If seats are limited, show the number remaining and the rate of change with auditability. Fake scarcity erodes trust fast.

Advanced Tactics: Redirecting Without Deception

Some illusions are about changing what’s salient, not hiding truth.

- Order effects: The first and last items are recalled best (primacy and recency). Put essential points in those slots. In meetings, reiterate the most important action at the end.

- Chunking and labeling: Group related items and label the group with an intuitive tag. The label becomes a cognitive handle; people carry more by “grabbing” the handle rather than each item.

- Negative space as a pointer: Empty space is not empty; it directs attention. Place ample whitespace around your priority element and compress space elsewhere.

- Contrast framing for nuance: Rather than saying “X is better,” show a side-by-side with 2–3 dimensions (cost, reliability, learning curve). Invite the user to conclude, which increases acceptance.

Persuasion Scripts for Specific Roles

-

Product managers

- Kickoff narrative: “Here’s what users are trying to do; here’s what they expect; here’s how we’ll meet them halfway.”

- Roadmap illusions: Stage early wins (fast loads, visible progress) before complex features. Momentum persuades stakeholders and users alike.

-

Sales and marketing

- Discovery: Ask users to predict their current cost or time-to-task; then show the measured number. The prediction gap creates a teachable moment without shaming.

- Demonstrations: Use controlled contrast—show the chaotic before, then the tidy after with synchronized audio and haptics if possible.

-

Educators

- Pretesting: Short quizzes before lessons activate priors and improve retention, even when students answer incorrectly.

- Visual hints: Use partially completed diagrams that prompt students to “fill in the missing lines,” leveraging the brain’s completion bias.

-

Leaders and facilitators

- Meeting momentum: Start with a micro-decision everyone can make in 60 seconds to establish a bias for action.

- Choice architecture: Present three options with a recommended middle path and a clear rationale. Invite dissent explicitly to reduce illusion of consensus.

Field Notes: Quick Wins Backed by Research

- Put the most important argument at the beginning and end; summarize in one sentence. Primacy and recency will do the rest.

- Use numbers with units and baselines: “Save 2.3 hours/week vs. your current workflow,” not “Save time.” Anchors need context.

- Visualize progress in steps, not an indeterminate spin. People feel less anxiety when they can predict the path.

- If you must deliver a wait, fill it with self-efficacy: “While we prepare your report, here’s a tip to strengthen your password.”

- Offer opt-outs visibly. When people sense control, they accept guidance more readily.

A Short Reading of the Mind’s Favorite Stories

The brain buys stories with certain structures:

- The progress tale: “You’re here; you want there; this is the bridge.” Progress bars and staged onboarding are visual versions of this.

- The contrast tale: “Old world vs. new world.” Before-and-after screenshots, carefully controlled, carry this narrative.

- The community tale: “People like you made this choice.” Social proof, used responsibly, gives a sense of shared reality.

- The mastery tale: “You thought X; you learned Y; here’s why it matters.” Pretests and micro-reveals encode this story in memory.

Crafting persuasion means matching your message to one of these schemas and making the beats easy to detect and feel.

Build Your Personal Toolkit

Keep a lightweight kit you can deploy on any project:

- Attention toolkit: One focal highlight per screen; gaze cues; whitespace; staggered reveals.

- Expectation toolkit: Anchors with baselines; transparent defaults; explicit time estimates.

- Time toolkit: Skeleton screens; front-loaded progress; goal-gradient displays; opt-out paths.

- Multisensory toolkit: Sync sound and haptics with visible events; redundancy for accessibility.

- Memory toolkit: Generation prompts; retrieval cues; time-stamped snapshots.

- Ethics toolkit: Reversibility test; informed consent for sensitive defaults; fairness audits.

Weekly practice routine:

- Monday: Run a pre-mortem on a live feature—how could this illusion mislead or exclude?

- Tuesday: A/B test one small attention change (spacing, gaze cue).

- Wednesday: Rewrite a key message using a different frame; test comprehension.

- Thursday: Add a progress visualization where you have a spinner.

- Friday: Share results and a one-paragraph “why it worked” note with your team.

Persuasion through illusion is not about lying; it’s about harmonizing with how brains naturally work. The brain craves structure, expects patterns, and fills gaps in ways that are often helpful, sometimes risky. Your job is to choreograph those tendencies—clearly, responsibly, artfully—so people can make better choices with less friction. If you set the right expectations, shape the right sensations, and respect autonomy at every step, the end experience will feel almost magical for the simplest reason of all: you designed for the mind that perceives it.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts