A Beginners Guide to Implementing Word Embeddings from Scratch

47 min read Step-by-step beginner’s guide to implementing word embeddings from scratch using Python, covering tokenization, CBOW/Skip-gram, training, evaluation, and practical tips. (0 Reviews)

Word embeddings turned the messy, symbolic world of words into something we can calculate with: continuous vectors where geometry encodes meaning. Words that occur in similar contexts end up near each other; arithmetic on vectors can reflect analogies like king − man + woman ≈ queen. In this guide, you'll implement classic word embeddings from scratch—not by downloading a library and calling a function, but by building key components step by step. You’ll learn how the data is prepared, how objectives are designed, how gradients flow, and how to evaluate whether your vectors learned anything useful at all.

Along the way, we’ll balance intuition with concrete implementation details and reliable practices that make small projects work. If you stick with it, you'll finish with a lightweight, reproducible, and understandable embedding pipeline you can adapt to your own corpus.

Why Word Embeddings Matter and What “From Scratch” Really Means

The core idea behind word embeddings is distributional semantics: words used in similar contexts tend to have similar meanings. A numerical embedding compresses distributional information into a dense vector of, say, 50–300 dimensions so we can compute similarities and feed them to machine learning models. Unlike one-hot vectors, embeddings are compact, continuous, and expressive.

From scratch means:

- You prepare raw text, build a vocabulary, and choose a context window.

- You build either a count-based co-occurrence representation and reduce it (e.g., SVD), or a predictive model (e.g., CBOW or Skip-gram) and optimize it.

- You control objectives (softmax vs negative sampling), learning rates, sampling distributions, and evaluation.

It doesn’t have to mean zero libraries. You can absolutely use NumPy and SciPy for arrays and SVD; what you avoid is an off-the-shelf embedding trainer that hides the learning process. You’ll understand where each matrix comes from, what its rows/columns mean, and how training progresses.

Practical benefits of doing it this way include:

- Auditability: You can inspect weights and gradients, replicate results, and debug logically.

- Customization: Tune context definitions (positional, directional, weighted), incorporate domain-specific preprocessing, or add your own regularizers.

- Education: Once you understand these building blocks, moving to more advanced models (fastText, contextual models) becomes straightforward.

Preparing Your Text: Tokenization, Normalization, and Corpora

Embeddings are only as good as your data. A small, noisy corpus yields weak vectors regardless of modeling. Before modeling, you need to:

-

Choose your corpus

- General-purpose: Wikipedia dumps, newswires, public web datasets.

- Domain-specific: Support tickets, scientific abstracts, legal filings. Domain text biases the geometry toward what matters in that field.

- Size: Even a few million tokens can produce useful embeddings; more data helps. Be mindful of licensing and privacy.

-

Normalize and tokenize

- Lowercasing: Often beneficial; can lose distinctions (e.g., Apple vs apple). Consider keeping case if your corpus is capitalization-informative.

- Punctuation: Strip or keep? For embeddings, removing most punctuation is fine; keep hyphens or apostrophes if morphological nuance matters.

- Numbers: Replace with a special token like

to reduce sparsity. - URLs, emails, emojis: Normalize to placeholders if frequent.

- Language: Tokenization rules differ; use a language-aware tokenizer for non-whitespace-languages (e.g., Chinese segmentation).

-

Build a vocabulary

- Minimum frequency threshold (min_count): Drop extremely rare tokens to reduce noise and memory; common values: 5–20 depending on corpus size.

- Special tokens:

for unknowns; only if you need fixed-length sequences (not typically needed for SGNS/CBOW).

-

Create training pairs with a sliding window

- Window size (e.g., 2–10): Controls context breadth. Small windows emphasize syntactic similarity; larger windows emphasize topical/semantic similarity.

- Dynamic window: Randomize window radius per center word to diversify context (Word2Vec does this).

Example: a minimal tokenizer and pair builder in Python, enough for small experiments:

import re

from collections import Counter, defaultdict

# Basic tokenizer: splits on non-word characters, keeps simple words

TOKEN_RE = re.compile(r"\w+")

def tokenize(text):

tokens = TOKEN_RE.findall(text.lower())

# Map numbers to a placeholder

return ['<num>' if t.isdigit() else t for t in tokens]

# Build vocabulary with min_count

def build_vocab(tokenized_docs, min_count=5):

counter = Counter()

for doc in tokenized_docs:

counter.update(doc)

vocab = {'<unk>': 0}

for w, c in counter.items():

if c >= min_count and w != '<unk>':

vocab[w] = len(vocab)

return vocab

# Convert tokens to ids with <unk>

def to_ids(tokens, vocab):

unk = vocab['<unk>']

return [vocab.get(t, unk) for t in tokens]

# Create (center, context) pairs using a symmetric window

def make_pairs(ids, window=5):

pairs = []

for i, center in enumerate(ids):

left = max(0, i - window)

right = min(len(ids), i + window + 1)

for j in range(left, right):

if j != i:

pairs.append((center, ids[j]))

return pairs

In real projects, consider spaCy or NLTK for tokenization, and clean aggressively (deduplicate, remove boilerplate).

The Simplest Baseline: One-Hot and Count Vectors

Before learning embeddings, build mental models with simple baselines:

- One-hot vectors: Each word maps to a unit vector e_i. Similarity between distinct words is zero—useless for semantics, but a reference point.

- Bag-of-words counts: Count how often word w appears in a document or context. Still sparse but now distances are meaningful.

Key insights:

- Sparsity: With a 50,000-word vocabulary, a one-hot vector is 50,000 dimensions, mostly zeros.

- Co-occurrence counts: Count how often words appear near each other in a window across the corpus. The resulting co-occurrence matrix X has shape |V| × |V|.

- Weighting helps: Raw counts favor frequent words—use TF-IDF or PMI to emphasize informative associations.

Toy example:

Suppose your corpus is: 'cats chase mice' and 'dogs chase cats'. With window size 1, context of 'chase' includes 'cats', 'mice', 'dogs'. The co-occurrence counts will reflect that 'cats' and 'dogs' both co-occur with 'chase', so they should be embedded closer than, say, 'mice' and 'dogs' which co-occur less frequently.

Limitations:

- High dimensionality: |V| × |V| is huge. Use sparse representations.

- Local vs global statistics: Count-based methods capture global co-occurrence. Predictive models (below) capture both local behavior and can be more scalable.

Building a Co-occurrence Matrix and a Basic SVD Embedding

Count-based embeddings compress a large co-occurrence matrix into a dense representation using matrix factorization. Steps:

- Build a symmetric co-occurrence matrix X, where X[i, j] is the number of times word j appears in the context of word i.

- Convert counts to a more informative scale like PMI (pointwise mutual information):

- PMI(i, j) = log( P(i, j) / (P(i) P(j)) )

- P(i, j) is co-occurrence probability; P(i) and P(j) are unigram probabilities.

- Use PPMI = max(PMI, 0) to avoid negative values dominating.

- Apply truncated SVD to PPMI to get low-dimensional vectors: X ≈ U Σ V^T; take W = U Σ^α for α ∈ [0, 1]. Many use α = 0.5.

Pros and cons:

- Pros: Simple, fast with sparse matrices, captures global statistics. Easy to inspect.

- Cons: Surface-level semantics; struggles with rare words; memory cost of |V| × |V|.

Minimal implementation sketch:

import numpy as np

from collections import defaultdict

from scipy.sparse import dok_matrix, csr_matrix

from sklearn.decomposition import TruncatedSVD

def build_cooc(docs_ids, vocab_size, window=5):

X = dok_matrix((vocab_size, vocab_size), dtype=np.float32)

for ids in docs_ids:

for i, wi in enumerate(ids):

left = max(0, i - window)

right = min(len(ids), i + window + 1)

for j in range(left, right):

if j != i:

wj = ids[j]

X[wi, wj] += 1.0

return X.tocsr()

def ppmi_matrix(X):

# X is csr sparse

total = X.sum()

row_sums = np.array(X.sum(axis=1)).ravel()

col_sums = np.array(X.sum(axis=0)).ravel()

# PMI(i,j) = log(P(i,j)/(P(i)P(j))) = log(X_ij * total / (row_i * col_j))

X = X.tocoo()

data = []

for i, j, xij in zip(X.row, X.col, X.data):

pmi = np.log((xij * total) / (row_sums[i] * col_sums[j] + 1e-10) + 1e-10)

data.append(max(pmi, 0.0))

P = csr_matrix((data, (X.row, X.col)), shape=X.shape)

return P

def svd_embed(P, dim=100, alpha=0.5):

svd = TruncatedSVD(n_components=dim, random_state=42)

U = svd.fit_transform(P)

S = svd.singular_values_

W = U * (S**alpha)

return W

This approach echoes ideas from classic latent semantic analysis and modern variants like GloVe (which uses a log-weighted objective over co-occurrence counts rather than PMI explicitly). For small-to-medium corpora, SVD-based embeddings can be surprisingly strong baselines.

Neural Word Embeddings: CBOW and Skip-gram Demystified

Predictive embeddings learn to predict a word from its context (CBOW) or predict context words from a center word (Skip-gram). Two parameter matrices are learned:

- W_in: |V| × d, mapping input word IDs to d-dimensional vectors.

- W_out: |V| × d, mapping to output space for prediction.

CBOW (Continuous Bag-of-Words):

- Input: Average (or sum) of context word embeddings around a center.

- Objective: Maximize probability of the center word given its context representation.

- Pros: Fast to train; stable performance.

Skip-gram (SG):

- Input: Center word embedding.

- Objective: Predict each surrounding context word.

- Pros: Does well on rare words because each context occurrence provides a signal.

In both cases, naive training with softmax over |V| classes per prediction is expensive. Approximations—negative sampling or hierarchical softmax—reduce cost dramatically.

What do W_in and W_out represent? After training, W_in rows are typically used as the embeddings. W_out may capture complementary information; some implementations average them or use W_in only. Empirically, W_in vectors are standard for downstream use.

Training Objective: Softmax, Negative Sampling, and Hierarchical Softmax

You want a loss that makes true (center, context) pairs score higher than random pairs. Three options:

-

Full softmax

- For Skip-gram, p(context | center) = softmax(W_out · h), where h is the center embedding.

- Loss per positive pair is −log p(true_context | center).

- Cost is O(|V|) per prediction: too expensive for large vocabularies.

-

Negative Sampling (SGNS)

- Replace softmax with k binary logistic regressions: one for the positive pair and k for negatives sampled from a noise distribution.

- Objective for center c and context o:

- L = −log σ(v_o · h_c) − Σ_{i=1..k} log σ(−v_{n_i} · h_c)

- Noise distribution: Unigram counts raised to the 3/4 power, normalized (as in Mikolov et al.). This steers negatives toward frequent words without overwhelming the model.

- Typical k: 5–20 for small corpora; 2–5 for very large.

- Cost per sample: O(k · d), independent of |V|.

-

Hierarchical Softmax

- Build a Huffman tree from word frequencies.

- Predict a path of binary decisions instead of a flat softmax.

- Cost is O(log |V|) per prediction; useful when k must be small or when you prefer exact probabilities.

When to use which:

- Negative sampling is the de facto standard for small-to-large corpora due to simplicity and performance.

- Hierarchical softmax can be a good fit for very large vocabularies when you care about probability calibration.

- Full softmax is rarely used for classic word embeddings, unless vocabulary is tiny.

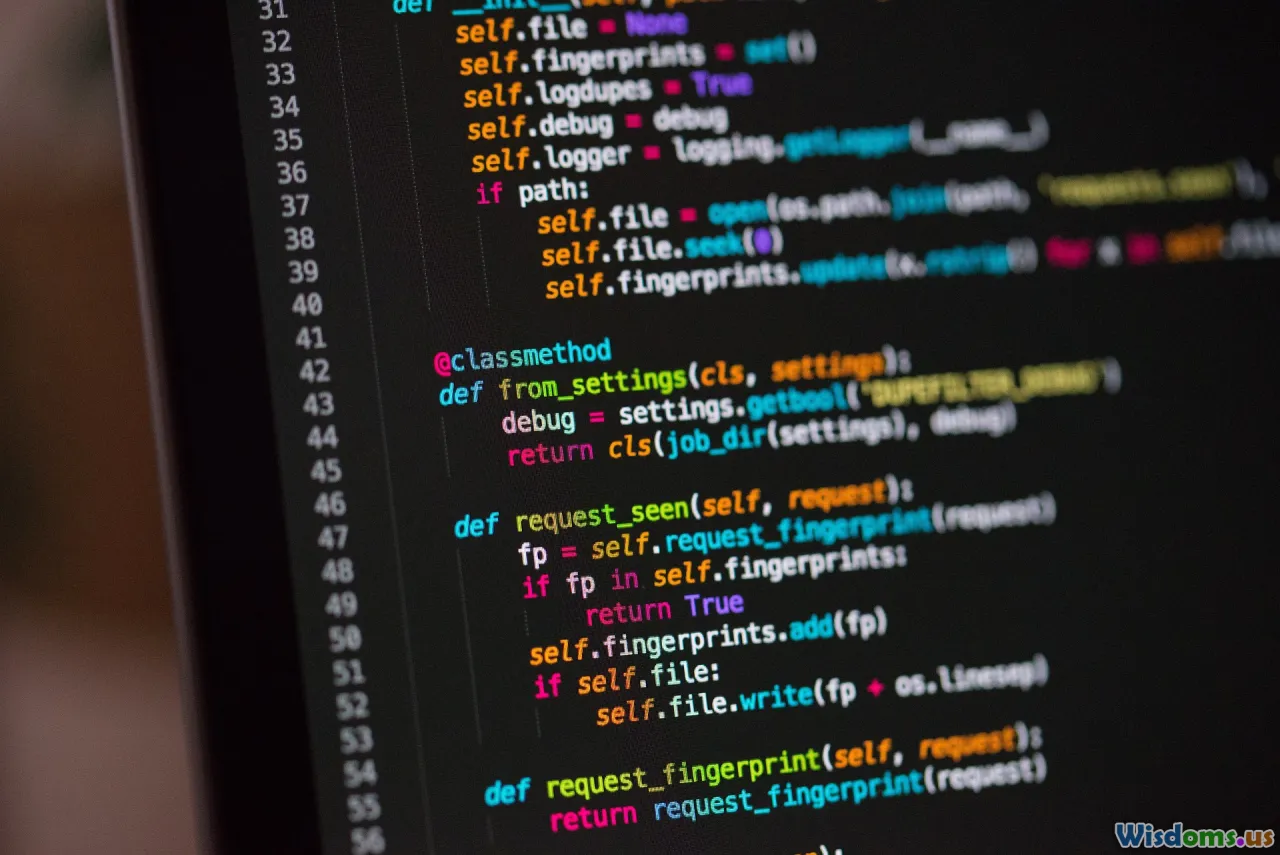

Implementing Skip-gram with Negative Sampling in NumPy

Below is a compact but complete SGNS implementation for learning word embeddings with NumPy. It is optimized for clarity rather than speed, so you can understand each step.

What it does:

- Builds a unigram noise distribution^0.75 for negative sampling.

- Uses a precomputed table for fast sampling (alias method would be faster for very large vocabs, but we keep it simple).

- Trains W_in and W_out by stochastic updates over (center, context) pairs.

import numpy as np

class SGNS:

def __init__(self, vocab_size, dim=100, neg_k=5, lr=0.025, seed=42):

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

self.vocab_size = vocab_size

self.dim = dim

self.neg_k = neg_k

self.lr0 = lr

# Initialize embeddings: small random values

self.W_in = (rng.random((vocab_size, dim)) - 0.5) / dim

self.W_out = (rng.random((vocab_size, dim)) - 0.5) / dim

self.rng = rng

@staticmethod

def sigmoid(x):

# Numerically stable sigmoid

out = np.empty_like(x)

pos = x >= 0

neg = ~pos

out[pos] = 1.0 / (1.0 + np.exp(-x[pos]))

expx = np.exp(x[neg])

out[neg] = expx / (1 + expx)

return out

def build_unigram_table(self, token_counts, power=0.75, table_size=10_0000):

# token_counts: array of length |V|

counts = np.array(token_counts, dtype=np.float64)

counts[0] = 1.0 # ensure <unk> has some mass

probs = counts ** power

probs /= probs.sum()

# build sampling table by multinomial expansion

table = np.zeros(table_size, dtype=np.int32)

cumulative = np.cumsum(probs)

j = 0

for i in range(table_size):

# find smallest j with cumulative[j] > i/table_size

r = (i + 1) / table_size

while j < len(cumulative) and cumulative[j] < r:

j += 1

table[i] = min(j, len(cumulative) - 1)

self.unigram_table = table

def sample_negatives(self, exclude, size):

# Sample from precomputed table, resample if equal to exclude

samples = []

while len(samples) < size:

idx = int(self.unigram_table[self.rng.integers(0, len(self.unigram_table))])

if idx != exclude:

samples.append(idx)

return np.array(samples, dtype=np.int32)

def train(self, pairs, epochs=1, batch_size=512):

# pairs: list of (center, context) ints

n = len(pairs)

for epoch in range(epochs):

# Shuffle pairs each epoch

self.rng.shuffle(pairs)

# simple linear decay of lr

lr = self.lr0

for start in range(0, n, batch_size):

end = min(start + batch_size, n)

batch = pairs[start:end]

# process each pair independently (could be vectorized further)

for c, o in batch:

h = self.W_in[c] # center vector

u_pos = self.W_out[o] # positive context vector

# Positive term

score_pos = np.dot(h, u_pos)

grad_pos = self.sigmoid(-score_pos) # d/dx -log(sigmoid(x))

# Negative samples

negs = self.sample_negatives(exclude=o, size=self.neg_k)

u_negs = self.W_out[negs]

score_negs = h @ u_negs.T

grad_negs = self.sigmoid(score_negs) # d/dx -log(sigmoid(-x))

# Update W_in[c]

grad_h = grad_pos * u_pos + (grad_negs @ u_negs)

self.W_in[c] += lr * grad_h

# Update positive output vector

self.W_out[o] += lr * (grad_pos * h)

# Update negative output vectors

self.W_out[negs] -= lr * (grad_negs[:, None] * h[None, :])

# Update learning rate schedule (simple decay)

lr = max(1e-4, lr * 0.999)

return self.W_in

Usage sketch with the preprocessing utilities above:

# Suppose tokenized_docs is a list of token lists

vocab = build_vocab(tokenized_docs, min_count=5)

docs_ids = [to_ids(doc, vocab) for doc in tokenized_docs]

# Build (center, context) pairs for all docs

pairs = []

for ids in docs_ids:

pairs.extend(make_pairs(ids, window=5))

# Compute counts for noise distribution

counts = [0] * len(vocab)

for ids in docs_ids:

for w in ids:

counts[w] += 1

model = SGNS(vocab_size=len(vocab), dim=100, neg_k=5, lr=0.025)

model.build_unigram_table(counts, power=0.75, table_size=200000)

W = model.train(pairs, epochs=2, batch_size=1024)

# W is your embedding matrix; rows align with vocab indices

Notes:

- The sampling table here is a simple cumulative method. For big vocabs, use alias sampling or reuse a larger table for uniform access.

- For speed, vectorize the updates over mini-batches.

- Real implementations often use subsampling of frequent words (drop frequent tokens with probability proportional to 1 − sqrt(t/f(w))) to reduce dominance of stopwords and speed training.

Practical Training Tips: Learning Rate, Batching, and Efficiency

-

Learning rate schedule

- Start around 0.025 for Skip-gram, decay to ~1e-3 across epochs. Linear decay is common and surprisingly effective.

- Too high and you’ll see exploding norms or oscillations; too low and training stalls.

-

Subsampling frequent words

- Heuristic: keep a token w with probability p_keep = sqrt(t / f(w)) + t / f(w), where t ≈ 1e-5.

- Drops many stopwords without removing them entirely.

-

Mini-batching and vectorization

- Compute dot products for a batch at once using matrix multiplies.

- Keep arrays contiguous in memory and prefer 32-bit floats when possible.

-

Negative sampling cache

- Pre-sample negatives for each batch to reduce Python overhead.

- Ensure negatives don’t include the positive target.

-

Initialization

- Small random uniform in [−1/d, 1/d] is fine; avoid large scales that saturate sigmoid early.

-

Regularization

- L2 regularization on W_out can help if you see exploding norms; apply lightly.

- Gradient clipping (by norm) at 5–10 can stabilize training.

-

Reproducibility

- Fix seeds for RNGs; log hyperparameters; save checkpoints with timestamps and git commit hashes.

-

Profiling

- Use time.perf_counter to track throughput (pairs/sec). Identify bottlenecks—often Python loops.

- If performance matters, consider Numba or a small PyTorch reimplementation with custom negative sampling to leverage GPU.

Handling Rare Words and Out-of-Vocabulary Terms

Rare words are challenging because they offer few contexts. You can mitigate this:

-

min_count threshold

- Removes extremely rare words and maps them to

. This reduces noise and memory.

- Removes extremely rare words and maps them to

-

Subword modeling (character n-grams)

- Instead of a single vector per word, represent a word as the sum of its character n-gram vectors (e.g., n = 3–6). This is the core idea of fastText.

- Helps with morphology ('walking', 'walked', 'walker') and OOVs: unseen words still decompose into seen n-grams.

-

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) or unigram LM tokenization

- Learn subword units data-driven; represent text as subword sequences which your embedding model learns.

-

Backoff strategies

- For truly new words at inference, use: average of known subwords; nearest neighbors of character-level edit distance; or map to

.

- For truly new words at inference, use: average of known subwords; nearest neighbors of character-level edit distance; or map to

-

Domain adaptation

- If you start from general embeddings and fine-tune on domain text, rare domain terms get better representations without training from scratch on massive data.

Evaluating Your Embeddings: Intrinsic and Extrinsic

Evaluation tells you whether your vectors reflect meaningful semantics. Two broad categories:

Intrinsic evaluation

-

Word similarity/relatedness

- Datasets: WordSim-353, MEN, SimLex-999, Rare Words (RW). Compute cosine similarity for word pairs and measure Spearman correlation with human ratings.

- Pitfall: High scores can reflect topical relatedness rather than true similarity; choice of window size affects this.

-

Analogies (a:b :: c:?)

- Classic example: king − man + woman ≈ queen.

- Compute nearest neighbor to vector v = w(a) − w(b) + w(c) and check accuracy on analogy datasets (Google analogies, BATS).

- Analogies test linear structure; results vary by training setup.

-

Neighborhood inspection

- For a few probe words (e.g., 'doctor', 'bank', 'python'), list nearest neighbors. Sanity check clusters.

Extrinsic evaluation

- Use embeddings as features in downstream tasks:

- Text classification sentiment/intent: Initialize an embedding layer with your vectors, freeze or fine-tune, compare accuracy.

- NER/Part-of-speech taggers: Measure F1 or accuracy changes.

Simple nearest neighbor utility:

import numpy as np

def normalize_rows(W):

norms = np.linalg.norm(W, axis=1, keepdims=True) + 1e-10

return W / norms

def nearest_neighbors(W, vocab, query_word, topk=10):

# W is embedding matrix; vocab is word->id dict

if query_word not in vocab:

return []

Wn = normalize_rows(W)

qid = vocab[query_word]

sims = Wn @ Wn[qid]

# exclude the query itself

sims[qid] = -np.inf

ids = np.argpartition(-sims, topk)[:topk]

return sorted([(w, float(sims[vocab[w]])) for w in vocab if vocab[w] in ids], key=lambda x: -x[1])

Track metrics over epochs; if cosine neighborhoods improve and loss decreases, you’re on the right path.

Inspecting and Visualizing Embeddings

Visualization helps you internalize what the model learned:

- PCA: Quick linear dimensionality reduction to 2D.

- t-SNE: Reveals local clusters; sensitive to perplexity (try 5–50) and random seeds.

- UMAP: Often preserves both local neighborhoods and some global structure; faster than t-SNE for large sets.

Example with scikit-learn:

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Pick a subset of words to visualize (e.g., top 1000 frequent)

ids_to_plot = list(range(1000))

W_subset = W[ids_to_plot]

labels = [w for w, i in sorted(vocab.items(), key=lambda x: x[1]) if i in ids_to_plot]

X2 = TSNE(n_components=2, perplexity=30, learning_rate='auto', init='random', random_state=42).fit_transform(W_subset)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 10))

plt.scatter(X2[:,0], X2[:,1], s=2, alpha=0.6)

for i, lbl in enumerate(labels[:200]): # annotate a subset for readability

plt.annotate(lbl, (X2[i,0], X2[i,1]), fontsize=8, alpha=0.7)

plt.title('t-SNE of word embeddings')

plt.show()

Look for coherent clusters: months, countries, technology terms, emotions. If the plot is a noisy blob, re-check preprocessing and training.

Common Pitfalls and How to Debug

-

Loss not decreasing

- Check learning rate: if near zero or too high, adjust.

- Ensure you're updating both W_in and W_out.

- Verify sigmoid implementation and that signs in gradients match the objective.

-

Degenerate vectors (all zeros or exploding norms)

- Initialize with small randoms; add gradient clipping; lower the learning rate.

- Confirm you’re not accidentally normalizing embeddings at every step.

-

Negative sampling bugs

- Don’t sample the positive target as a negative.

- Use a separate distribution (unigram^0.75), not uniform.

- Avoid reusing the same negative too often within a batch unless intended.

-

Window construction mistakes

- Ensure symmetric windows; exclude the center itself.

- Shuffle contexts if you process by sentence to avoid periodicity.

-

Off-by-one errors in vocab mapping

- Keep a single authoritative mapping from word to index.

- Assert shapes consistently: W_in.shape == (|V|, d).

-

Memory overload with large co-occurrence

- Use sparse formats (CSR) and prune contexts beyond a threshold.

- For SVD, cap window size or limit to top-N frequent words.

-

Evaluation mismatches

- Ensure words in evaluation sets exist in your vocab; otherwise skip or map to

and report coverage.

- Ensure words in evaluation sets exist in your vocab; otherwise skip or map to

-

Reproducibility drift

- Fix seeds in all random calls.

- Log corpus versions and preprocessing flags; slight changes can shift results.

When to Prefer Pretrained vs. From-Scratch

From-scratch embeddings make sense when:

- Your domain is specialized (medical, legal, code) and general embeddings won’t capture your jargon.

- You need control over the vocabulary (e.g., privacy filtering, custom tokens).

- You’re prototyping educational tools or research ideas.

Pretrained embeddings are better when:

- You lack sufficient data; pretrained vectors capture rich semantics from billions of tokens.

- You need quick, robust baselines for general tasks.

- You plan to fine-tune a model downstream anyway; starting from strong initial vectors accelerates convergence.

Hybrid approach:

- Start with pretrained vectors for shared words; initialize new words randomly; fine-tune on your corpus. This balances general knowledge with domain specificity.

Extending to Subword and Contextual Embeddings

Beyond classic word embeddings:

Subword (fastText-style)

- Represent each word as a sum of vectors for its character n-grams plus an optional whole-word vector.

- Training still uses SGNS, but gradients update many n-gram vectors per token.

- Advantages: Handles OOVs, better morphology, smoother representations.

Sketch for character n-grams:

def char_ngrams(word, min_n=3, max_n=6):

word = f'<{word}>'

grams = set()

for n in range(min_n, max_n+1):

for i in range(len(word)-n+1):

grams.add(word[i:i+n])

return grams

You would maintain an embedding table for all n-grams, hash them into a fixed-size bucket array, and use the sum as the word representation during training and inference.

Contextual embeddings (ELMo, BERT, GPT)

- Produce a different vector for the same word depending on its sentence context.

- Usually trained with language modeling objectives and transformer architectures.

- From-scratch implementation is a large undertaking; however, understanding word2vec makes it easier to grasp how contextual models build on distributional semantics.

When to switch:

- If your downstream tasks require nuanced, context-dependent meaning (e.g., WSD, QA), contextual embeddings outperform static ones. For pure lexical similarity or simple classifiers, well-trained static embeddings often suffice and are light-weight.

A Tiny End-to-End Plan and Checklist

Follow this compact plan to go from raw text to usable vectors:

-

Data and preprocessing

- Gather or sample at least a few million tokens for stable results.

- Tokenize; normalize digits to

; consider lowercasing. - Build vocab with min_count between 5 and 20.

-

Pair generation

- Use a symmetric window size of 5; experiment with dynamic windows.

- Implement subsampling of frequent words with t ≈ 1e-5.

-

Modeling choice

- Start with SGNS (Skip-gram with negative sampling) at d=100–300, neg_k=5–10.

- Alternatively, build a PPMI matrix and run TruncatedSVD for a strong baseline.

-

Optimization

- Initialize lr=0.025; decay linearly each epoch.

- Batch updates; vectorize dot products.

- Clip gradients at norm 5 if needed.

-

Monitoring

- Track average loss per 100k pairs.

- Inspect nearest neighbors for sanity (doctor → physician, hospital, nurse; python → java, programming, ruby).

-

Evaluation

- Intrinsic: correlation on MEN/WS-353, analogies accuracy if applicable.

- Extrinsic: plug into a small classifier and compare against random embeddings.

-

Refinement

- Tune window size: 2–5 for syntax, 5–10+ for topical similarity.

- Adjust neg_k: more negatives can help, at compute cost.

- Try subword modeling if OOVs matter.

-

Packaging

- Save embeddings in a clean format: TSV with word and vector or NumPy binary with a separate vocab JSON.

- Provide a small inference script for nearest neighbors and similarity.

-

Documentation

- Record corpus, preprocessing choices, hyperparameters, and evaluation metrics.

-

Reusability

- Wrap your trainer in a function or class; expose flags for dim, window, min_count, neg_k, and lr.

A minimalist example of saving vectors:

import json

import numpy as np

# vocab: dict word->id; W: np.ndarray

id_to_word = {i: w for w, i in vocab.items()}

np.save('embeddings.npy', W)

with open('vocab.json', 'w') as f:

json.dump(id_to_word, f)

# Later, load and query

W = np.load('embeddings.npy')

with open('vocab.json') as f:

id_to_word = json.load(f)

word_to_id = {w: int(i) for i, w in id_to_word.items()}

As you go through these steps, be patient with iteration. Embeddings improve with better data curation and careful hyperparameter tuning.

Training word embeddings from scratch is an empowering exercise: you see how textual co-occurrence becomes geometry, how objectives sculpt the space, and how simple tricks like negative sampling and subsampling make the difference between theory and practice. With a small set of utilities and a clear pipeline, you can produce vectors tailored to your domain, inspect what they’ve learned, and deploy them as compact, effective features in downstream systems. Keep your code simple, your measurements honest, and your corpus clean, and your vectors will tell a compelling story about your text.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts