A Step by Step Guide to Solving Impossible Problems

31 min read A practical, step-by-step framework to tackle 'impossible' problems using first principles, reframing, constraints, rapid experiments, and decision tools, with real examples from Apollo 13 to startup pivots. (0 Reviews)

Some problems feel like brick walls: your plan rebounds, the clock ticks, and the stakes climb. Yet history is full of teams and individuals who have turned “impossible” into “done.” They weren’t superhuman. They used a repeatable set of techniques that turn ambiguity into motion, motion into evidence, and evidence into solutions.

This guide lays out that playbook. It’s a practical, step-by-step approach you can apply to a moonshot at work, a civic challenge, or a gnarly technical issue. Along the way are examples, checklists, and traps to avoid.

Why “impossible” rarely means impossible

When we label a problem impossible, we’re often reacting to missing information, hidden assumptions, or the cost of early attempts. Consider a few examples:

- Apollo 13: After an onboard explosion crippled the spacecraft in 1970, NASA engineers had to improvise on-the-fly fixes, including building a carbon-dioxide scrubber from tape, plastic bags, and flight manuals. The problem didn’t shrink; the team reframed and decomposed it into solvable subproblems, attacking the most time-critical constraints first.

- Polio vaccine field trials (1954): The largest medical trial in history at that time enrolled over a million children. The logistical complexity looked unmanageable until organizers standardized protocols and used randomized, double-blind methods to translate uncertainty into interpretable evidence.

- AlphaFold (2020): Predicting protein structures once seemed out of reach at scale. The breakthrough came from reframing: turning molecular physics into a pattern recognition problem amenable to deep learning, then iterating on benchmarking contests (CASP) to drive rapid feedback.

Takeaway: “Impossible” is often a symptom of three things: the problem is poorly framed, the constraints are unexamined, or the feedback loops are too slow.

Step 1: Frame the right problem

Most messes persist because we rush to solutions before we understand what we’re solving. Use a simple template:

- Job to be done: Who is the beneficiary, and what progress do they seek? (“A community wants flood resilience that keeps schools open 95% of the year, even under once-in-25-year storms.”)

- Success condition: Define a measurable, time-bound outcome. (“Reduce disaster-related school closures from 15 days per year to fewer than 3 within 18 months.”)

- Non-goals: What good things will you explicitly not pursue this round? (“We won’t redesign the entire sewage network; we will target two high-risk districts.”)

Techniques to sharpen framing:

- Five Whys: Ask “why?” until you reach a root cause. Suppose app engagement is down. Why? Notifications are ignored. Why? They’re irrelevant. Why? They’re generic. Why? We don’t segment users. Why? Data pipeline lacks real-time processing. Now the problem to solve isn’t “make the app fun;” it’s “enable real-time segmentation within 90 days.”

- Counterfactual framing: “What would have to be true for this to work?” Listing conditions exposes critical assumptions you can test early.

- Inversion: “If we wanted to guarantee failure, what would we do?” The inverted list often reveals pitfalls and missing safeguards.

Example: A city labeled congestion “impossible” because expanding roads was maxed out. After reframing to “cut total commute time by 20%,” the solution set expanded: synchronized lights on priority corridors, employer-subsidized off-peak transit, and dynamic curb pricing for ride-hails. The outcome target aligned stakeholders and unlocked options other than asphalt.

Step 2: Map constraints and degrees of freedom

List constraints in two columns: hard (laws of physics, regulation, non-negotiable safety) and soft (customs, preferences, historical budgets). Mark each soft constraint with a price tag: what would it cost—in goodwill, dollars, or time—to relax it?

- Hard examples: Maximum payload mass for a drone, building codes, cryptographic properties of a protocol.

- Soft examples: “We’ve always shipped quarterly,” or “Marketing owns pricing,” or “Vendors require 90-day terms.”

Then list degrees of freedom—the knobs you can turn:

- Scope: Which segments, geographies, or use cases?

- Quality: What defect rate is tolerable at each stage of rollout?

- Resources: People, budget, compute capacity, partnerships.

- Sequencing: What can be parallelized? What must be serialized?

Practical exercise—Assumption wall:

- Fill a wall (physical or digital) with every statement you believe about the problem.

- Mark each as law (proven), policy (chosen), preference (habit), or guess (unknown).

- Target guesses for testing and policies for deliberate reconsideration.

Example: A supply chain team said same-day delivery was impossible outside major cities. A constraint map revealed that the “impossible” zone was an artifact of a preference (shipping only from central hubs) combined with a guess (micro-fulfillment centers would be cost-ineffective). A pilot using partner retail stores as nodes cut last-mile times 35% and met cost targets once order batching was optimized.

Step 3: Decompose with multiple lenses

Hard problems yield to decomposition—the art of splitting a monster into manageable parts. Use multiple lenses, not just a hierarchical breakdown, to avoid blind spots:

- Functional: Inputs, transformation, outputs. Example: Desalination involves feedwater intake, pretreatment, membrane separation, brine management, and power supply.

- Temporal: What happens before, during, after? Useful for onboarding flows, safety-critical procedures, or emergency responses.

- Spatial: Where is the action? For wildfires: ignition points, spread corridors, defensible zones, and refuge areas.

- Stakeholder: User, operator, regulator, neighbor; what does each need and fear?

- Failure mode: How can each component fail? What are early warning indicators?

Tools:

- MECE lists (mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive) to avoid overlap and gaps.

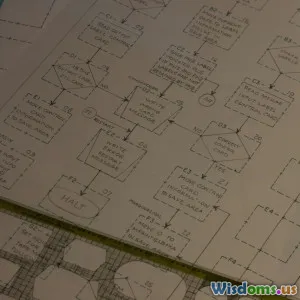

- Swimlane diagrams to map cross-team handoffs (often where delays hide).

- Interface contracts that specify what each module must provide and accept.

Example: A university struggled to raise completion rates. An organizational decomposition showed three bottlenecks: course scheduling conflicts, advising overload, and emergency financial gaps. Solving each independently (more evening sections; AI triage for advising; a small, fast microgrant fund) produced a combined impact of +9 percentage points in on-time graduation.

Step 4: Generate candidate paths systematically

The first idea is rarely the best. Structured ideation broadens the search space:

- SCAMPER: Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, Reverse. For urban waste, “Reverse” led one city to pick up recycling on demand via an app, reducing contamination by 30%.

- TRIZ patterns: Contradictions drive breakthroughs. If you need high strength but low weight, seek materials or structures (e.g., lattice composites) that resolve the tension rather than compromise.

- Morphological analysis: List key variables and enumerate combinations. For last-mile delivery, variables might include vehicle type (bike, scooter, van), storage (ambient, chilled), pickup node (store, locker), routing window (fixed, dynamic). A simple matrix exposes unconventional pairings worth piloting.

- Analogy mining: Ask “Who solved a similar problem in a different domain?” The way air traffic control manages capacity inspired a hospital’s bed management dashboard.

Set rules: separate divergence (volume, no judgment) from convergence (scoring, pruning). Use explicit criteria for scoring such as expected value, cost to test, and option value (what it enables later).

Example: A startup facing “impossible” cold-start for a marketplace listed 28 candidate paths. A scoring round based on cost-to-evidence favored three: bundling with an existing SaaS, targeting a niche where both sides already co-located (coworking spaces), and creating a high-signal waitlist event to concentrate supply and demand. Two sprints later, they had the data to drop 25 ideas without regret.

Step 5: Build cheap proofs before bold bets

Impossible problems get cheaper when you de-risk them in slices. Build “cheap proofs”—experiments, simulations, and back-of-the-envelope estimates that expose false paths early.

- Fermi estimates: Use orders of magnitude to sanity-check feasibility. If a city wants to replace short car trips with cargo bikes, estimate potential tonnage: number of short trips per day × average payload × conversion rate. If the required fleet is implausibly large, you pivot to hybrid approaches.

- Wizard-of-Oz prototypes: Mimic complex systems with manual effort to validate behavior before building automation. A language-learning app validated a spaced repetition model by having tutors orchestrate the schedule by hand for 50 learners.

- A/B and sequential testing: For digital products, use small, ethically sound experiments. Define guardrails (no more than X% performance degradation for key metrics) and stop-evaluate rules to avoid harm.

- Rapid physical prototypes: Use off-the-shelf components and foam-core mockups. A team exploring modular flood barriers created 1:100 scale models and validated interlocks with a garden hose and flow meter, revealing leakage issues before CNC machining.

Checklist for experiments:

- Hypothesis stated in if-then form.

- Success/failure thresholds precommitted.

- Minimal sample to detect a large effect (use a simple calculator or rule-of-thumb rather than guessing).

- Ethical review for any human-impacting test.

- Plan for what you’ll do if results are inconclusive.

Step 6: Trust contrarian data, not opinions

When stakes are high, opinions multiply. Tie decisions to evidence:

- Baselines and deltas: Know “what normal looks like.” If you claim a 20% improvement, 20% over what and measured how?

- Guardrail metrics: Protect against Goodhart’s Law. If you optimize delivery time, also track damage rates and customer complaints.

- Bayesian mindset: Update beliefs as evidence arrives. A small positive result from a noisy experiment should shift confidence a little, not crown a winner.

- Pre-mortem and red-team reviews: Before launch, ask a group to argue how your plan fails. Reward them for finding credible flaws.

Example: A climate analytics firm debated whether satellite-derived soil moisture could reliably predict crop stress weeks in advance. Half the team was skeptical. A blind, pre-registered study defined accuracy thresholds against ground truth sensors. The result was modest: a 12–15% improvement for certain crops, below the hype but above the break-even point for targeted insurance products. By letting data, not enthusiasm, decide scope, they saved a year of overbuild.

Step 7: Design for iteration at the bottleneck

Your speed of learning is limited by the slowest feedback loop. Identify it and re-architect around it.

- Theory of Constraints: Map your system from input to outcome. Where do work items queue? What takes the longest? That’s the constraint.

- Exploit, don’t ignore, the constraint: Increase utilization by batching cleverly, reducing setup time, or moving prep work upstream.

- Elevate with targeted investment: Add capacity only where it unblocks learning. Tooling elsewhere is noise.

Examples:

- Battery R&D: If cell fabrication takes two weeks, your iteration pace is capped. Teams that pre-screen chemistries via automated coin-cell rigs and validated simulations increase learning cycles 3–5x before committing to full cells.

- Policy change: If stakeholder sign-off is the bottleneck, build a cadence of brief, decision-ready memos (one pager with options, trade-offs, and a recommended path) instead of sprawling decks that invite endless debate.

Measure the loop:

- Cycle time: Idea to evidence.

- Batch size: Work-in-progress per iteration.

- Learning throughput: Decisions made per week based on new evidence.

A team that cut prototype cycle time from 20 to 5 days tripled their useful learning without hiring a soul.

Step 8: Partner with the problem and its stakeholders

Impossible problems are usually social as much as technical. Success requires aligning incentives and expectations.

- Map stakeholders: Beneficiaries, operators, funders, regulators, critics. For each, list desired outcomes, fears, and veto points.

- Adversarial collaboration: Pair proponents and skeptics to co-design tests. Skeptics help define failure conditions; proponents ensure the test is fair and feasible.

- Field immersion: Spend time where the problem lives. A team redesigning incident response learned more in two nights with on-call engineers than in weeks of whiteboard sessions.

- Communication contracts: Decide how you’ll communicate status and risks. A single source of truth beats a dozen threads.

Example: A regional grid operator exploring demand response—paying customers to reduce usage at peak—faced pushback from manufacturers. A series of on-site workshops revealed that shutdowns were indeed costly, but micro-adjustments (slowing certain motors for minutes) were acceptable. The program pivoted to granular controls and transparent pricing signals, gaining adoption without political fights.

Step 9: Decide under deep uncertainty

You won’t have perfect information. Good strategy makes progress despite that.

- Regret minimization: Ask which choice you’ll wish you had made when new information arrives. If learning is crucial, pick the option that teaches the most at acceptable cost.

- Real options: Structure work as stages with explicit go/no-go gates. Each stage buys the right, not the obligation, to invest more. Document the triggers.

- Robustness over optimality: Favor plans that work across many scenarios rather than maximum performance in one.

- Value of Information (VoI): Estimate whether an experiment is worth running. If a $50k test can prevent a $2M misstep with 10% probability, it’s a bargain.

Example: A company debated building its own data center vs. staying in the cloud. The cloud seemed pricier at scale, but offered faster iteration. They treated on-prem as an option: first optimize cloud costs, then run a limited on-prem pilot to learn about operational overhead. The option to expand remained; no irreversible commitments were made until evidence supported them.

Patterns from famous “impossible” wins

- Apollo 13: Constraint-first triage, ruthless prioritization (life support over everything), and creative reuse of on-hand materials. Pattern: when time is scarce, reorder work by survivability and create a physical/virtual “bench” of compatible parts.

- Cryptanalysis at Bletchley Park: They decomposed a vast search space using crib-based reductions and early computing. Pattern: reduce problem entropy by exploiting structure before throwing brute force at it.

- Eradicating smallpox: Global coordination, ring vaccination, and relentless surveillance. Pattern: design interventions that target transmission nodes with feedback loops that reveal outbreak edges quickly.

- The Human Genome Project: Originally projected at 15 years; finished early by parallelizing sequencing and pushing automation. Pattern: build tools that accelerate the work rather than just working harder.

- AlphaGo/AlphaZero: Self-play to generate training data when labeled data was scarce. Pattern: bootstrap learning by constructing an environment that rewards exploration.

Across these, you see repeatable habits: explicit constraints, clever decomposition, accelerated feedback cycles, and option-like staging.

Common failure modes and how to avoid them

- Solutionism: Starting with a favorite tool and searching for a problem. Fix by writing a problem statement stakeholders sign off on before building.

- Local maxima: Incremental improvements flatten out. Fix by occasionally exploring radically different approaches (spring clean your assumption wall).

- Premature scaling: Building for millions when you have dozens of users. Fix by a stage-gated plan tied to evidence thresholds (e.g., churn below X% for Y months).

- Goodhart’s Law: Metrics that become targets stop being good metrics. Fix with guardrails and periodic metric audits.

- Analysis paralysis: Waiting for perfect data. Fix by defining “good enough to decide” thresholds and precommitting to move.

- Blind spot stakeholders: Ignoring operators or end users. Fix with field immersion and direct feedback channels.

- Cargo cult process: Copying a famous team’s rituals without their underlying constraints or aims. Fix by articulating why each process step exists in your context.

Real-world example: A civic tech project aimed to digitize permit approvals. After a year of specs and prototypes, adoption lagged. A visit to permitting offices showed the true blocker: a legal requirement for wet signatures. The “software” problem was actually a policy constraint. A short legal reform, coupled with kiosks for small contractors, delivered a 60% cycle-time reduction in three months.

Tools you can use tomorrow

-

Problem statement template:

- Beneficiary and outcome: Who benefits and how will we measure success?

- Constraints: Hard vs. soft, with costs to relax.

- Assumptions: Ranked by uncertainty and impact.

- Decision cadence: How often will we decide, and what evidence counts?

-

Evidence plan:

- Top three hypotheses, each with: test method, sample size rough estimate, success/failure thresholds, and ethical check.

- Data hygiene: Baselines, definitions, and where the data lives.

-

Decomposition toolkit:

- Swimlanes for handoffs.

- Failure modes and effects lists.

- Interface contracts for module boundaries.

-

Iteration accelerator:

- Kanban with explicit WIP limits to keep batches small.

- “One-pager” decision memos: problem, options, trade-offs, recommendation, next evidence.

- Demo day every two weeks: show learning, not just features.

-

Stakeholder alignment:

- RACI (responsible, accountable, consulted, informed) for major decisions.

- Red-team schedule: a rotating group tests your assumptions monthly.

- Public changelog: a single source of truth on what changed and why.

A step-by-step walkthrough on a tough example

Problem: A coastal city faces street flooding after heavy rain. Traditional fixes—bigger pipes—are too expensive and slow. Leaders call it “impossible without billions.”

Step 1: Frame the right problem

- Success condition: Reduce flood-related street closures by 70% in two years in three pilot districts.

- Non-goals: Citywide overhaul; entirely eliminating floods.

Step 2: Map constraints and degrees of freedom

- Hard: Rain intensity trends, topography, safety standards.

- Soft: Procurement rules; coordination between departments.

- Degrees of freedom: Permeable surfaces, green infrastructure, dynamic street use, community programs, predictive maintenance.

Step 3: Decompose with multiple lenses

- Functional: Water capture, temporary storage, conveyance, and controlled release.

- Spatial: Alleyways, rooftops, parks, parking lots.

- Stakeholder: Residents, sanitation, parks, transportation, insurers.

Step 4: Generate candidate paths

- SCAMPER led to “Put to another use”: schoolyards as dual-use detention basins during storms.

- Analogy mining: “Sponge city” concepts from Asia; rooftop rain gardens from Northern Europe.

- Morphological matrix surfaced combinations like permeable paving + smart curb sensors + pop-up bike lanes that double as detention zones.

Step 5: Build cheap proofs

- Fermi estimate suggested that converting just 10% of impermeable surfaces in pilot districts could reduce peak runoff enough to meet targets.

- Wizard-of-Oz: Manual traffic redirection during a storm to test whether temporary bike lanes reduce flooding in known hotspots.

- Physical prototype: Small-scale retention basins in a park, instrumented with low-cost sensors, to validate infiltration rates.

Step 6: Use contrarian data

- Baseline: Map current closure durations and locations.

- Guardrails: Ensure emergency access times are not degraded.

- Pre-registered: If temporary lane conversions do not cut peak pooling by at least 20% at hotspots, pivot.

Step 7: Iterate at the bottleneck

- Bottleneck: Permitting and inter-department approvals.

- Fix: Decision one-pagers with standard checklists; weekly standing review across departments; templated contracts for rapid green-infrastructure installs.

Step 8: Partner with the problem

- Residents worried about parking loss. Pilot included dynamic signage and resident-preference windows.

- Maintenance: Partnered with community groups to monitor inlets and report blockages via an app, with micro-payments for verified reports.

Step 9: Decide under deep uncertainty

- Real option staging: Start with two neighborhoods; expand once closure metrics improved for two consecutive rainy seasons.

- VoI: Invest in a weather radar node to improve storm nowcasting—relatively small cost for big planning benefits.

Outcome: Within 18 months, closures fell by 62% in pilot districts; insurance claims for flood-related vehicle damage dropped 28%. With data in hand, the city expanded the program with state funding.

Advanced tips for stubborn barriers

- Use timeboxing to force learning: Put a fixed time on exploration, then decide. Indefinite research quietly drains momentum.

- Create parallel bets with shared learning: Multiple approaches feeding a common metrics dashboard. Kill or continue decisions every two weeks.

- Build a contradiction map: Write pairs like “fast vs. safe,” “cheap vs. robust.” For each, imagine designs that give you both via clever structure (e.g., pre-approved modules for safety that assemble quickly).

- Formalize risk burndown: Plot known risks and their severity over time. Every sprint should retire or reduce at least one top risk.

- Pre-solve communications: Draft the press release or executive FAQ for your future launch. If the story is incoherent or lacks numbers, your plan likely is too.

The step-by-step checklist

- Write the problem statement with success criteria and non-goals.

- Build an assumption wall; classify hard vs. soft constraints and tag soft ones with relaxation costs.

- Decompose the problem functionally, temporally, spatially, by stakeholders, and by failure modes.

- Generate a broad option set using SCAMPER, TRIZ, analogies, and morphological analysis.

- Score options using expected value, cost-to-evidence, and option value; pick a small portfolio to test.

- Design cheap proofs: Fermi estimates, prototypes, controlled experiments, simulations.

- Establish guardrail metrics, baselines, and pre-registered thresholds.

- Map your bottleneck; change process and tooling to accelerate the slowest loop.

- Engage stakeholders through adversarial collaboration and field immersion; set communication contracts.

- Make staged decisions using regret minimization and real options; calculate VoI for key experiments.

- Track risk burndown and learning throughput; celebrate retired risks, not just shipped features.

- Repeat: reframing, constraints, decomposition, options, proofs, decisions.

Bringing it all together

Solving the “impossible” isn’t about genius flashes or heroic all-nighters. It’s the disciplined craft of asking sharper questions, finding leverage in constraints, and accelerating the learning loop. The teams that win reduce uncertainty deliberately: they define success in measurable terms, design experiments that honor ethics and reality, and communicate a path others can follow.

You won’t get every bet right. That’s the point. By structuring work as a sequence of cheap proofs and staged commitments, you reserve your resources for the approaches that deserve them. When someone says “it can’t be done,” treat it as a prompt: Which assumption? Which constraint? Which feedback loop? Then pull out this playbook and start.

A final nudge: pick one problem on your plate today and run the first three steps—frame the outcome, map constraints, and decompose with two lenses. You’ll likely see at least one new path by lunchtime. And that’s how impossible starts to become inevitable—one clear step at a time.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Problem Solving

Popular Posts