Can Personality Tests Predict Criminal Behavior

30 min read Do personality tests reliably predict criminal behavior? Explore evidence on Big Five traits, psychopathy measures, recidivism risk, and ethical limits of using personality in justice settings. (0 Reviews)

Can Personality Tests Predict Criminal Behavior?

The question sounds like the premise of a true-crime documentary: hand someone a questionnaire, score a few scales, and forecast their likelihood of breaking the law. It’s a gripping idea, and it has practical stakes for courts, corrections, employers, and the public. But the reality is both more nuanced and more useful than a simple yes or no.

Personality tests can tell us something about tendencies: impulse control, empathy, antagonism, rule-following, sensation seeking. These are psychologically meaningful traits that correlate with many life outcomes, including some that overlap with criminal behavior. They are not crystal balls. Understanding what these tools can and cannot do—statistically, ethically, and operationally—is the difference between responsible risk management and harmful pseudoscience.

This article takes a deep, practical look at the science, the metrics, and the real-world use cases. You’ll learn where personality assessments add value, where they fail, and how to use them responsibly alongside other data.

What Personality Tests Are—and Are Not

Personality tests are standardized tools designed to measure relatively stable patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Under that umbrella sit several distinct families:

- Broad trait inventories: Big Five/FFM measures (e.g., conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, extraversion, openness). These are common in research and organizational settings.

- Clinical personality and psychopathology instruments: MMPI-2-RF/MMPI-3, PAI, and related tools developed for clinical/forensic assessment.

- Specific risk-related constructs: measures of psychopathy (e.g., PCL-R, Triarchic scales), antisocial attitudes, impulsivity, and hostility.

- Behavioral and performance-based measures: go/no-go tasks for inhibitory control, delay discounting tasks, and observer ratings.

What they are not:

- Oracles: No instrument can deterministically “tell the future” for an individual.

- Standalone decision engines: Ethical practice demands that test results be considered with history, context, corroboration, and professional judgment.

- Immutable labels: Personality interacts with age, environment, and interventions. Traits are relatively stable, not fixed.

A practical lens: A Big Five report might tell you someone scores low on conscientiousness (associated with poorer rule compliance) and low on agreeableness (higher antagonism). That profile can raise concerns about misconduct risk in certain settings. But the same person might function without issues under clear supervision and rewards for compliance. Context shapes expression.

What the Science Says: Traits and Crime Are Related—but Modestly

Over decades, meta-analyses have examined how personality relates to delinquency, aggression, and recidivism. A consistent story emerges:

- Agreeableness and Conscientiousness show the strongest inverse relationships with antisocial behaviors. Typical correlations (r) fall around -0.20 to -0.30 depending on outcome and sample. In plain terms, people lower on these traits are, on average, more likely to engage in rule-breaking and aggression.

- Psychopathy-related traits—especially callous-unemotional features, low empathy, and boldness/disinhibition—are associated with higher rates of violent behavior and recidivism. Observer-rated psychopathy (e.g., PCL-R) tends to predict outcomes better than brief self-reports.

- Neuroticism links less consistently to crime per se, but higher negative emotionality is associated with reactive aggression in some contexts.

- Sensation seeking and impulsivity show positive relationships with early onset delinquency and substance-related offenses.

Two crucial qualifiers:

-

Correlations are not destiny. An r of -0.25 is meaningful for groups but weak for individuals. It means traits contribute to risk; they don’t define it.

-

Outcomes differ. Predicting “any arrest” is not the same as predicting “serious violent reoffense within two years.” Predictive strength varies by the specificity and severity of the outcome.

A real-world example: In community corrections, low agreeableness and conscientiousness combined with a history of rule violations often forms a recognizable pattern. Adding structured risk factors (prior convictions, substance misuse, age at first offense) usually improves prediction far more than traits alone.

What Counts as Prediction? Understanding the Metrics

To judge whether a test “predicts,” you need to know the yardsticks.

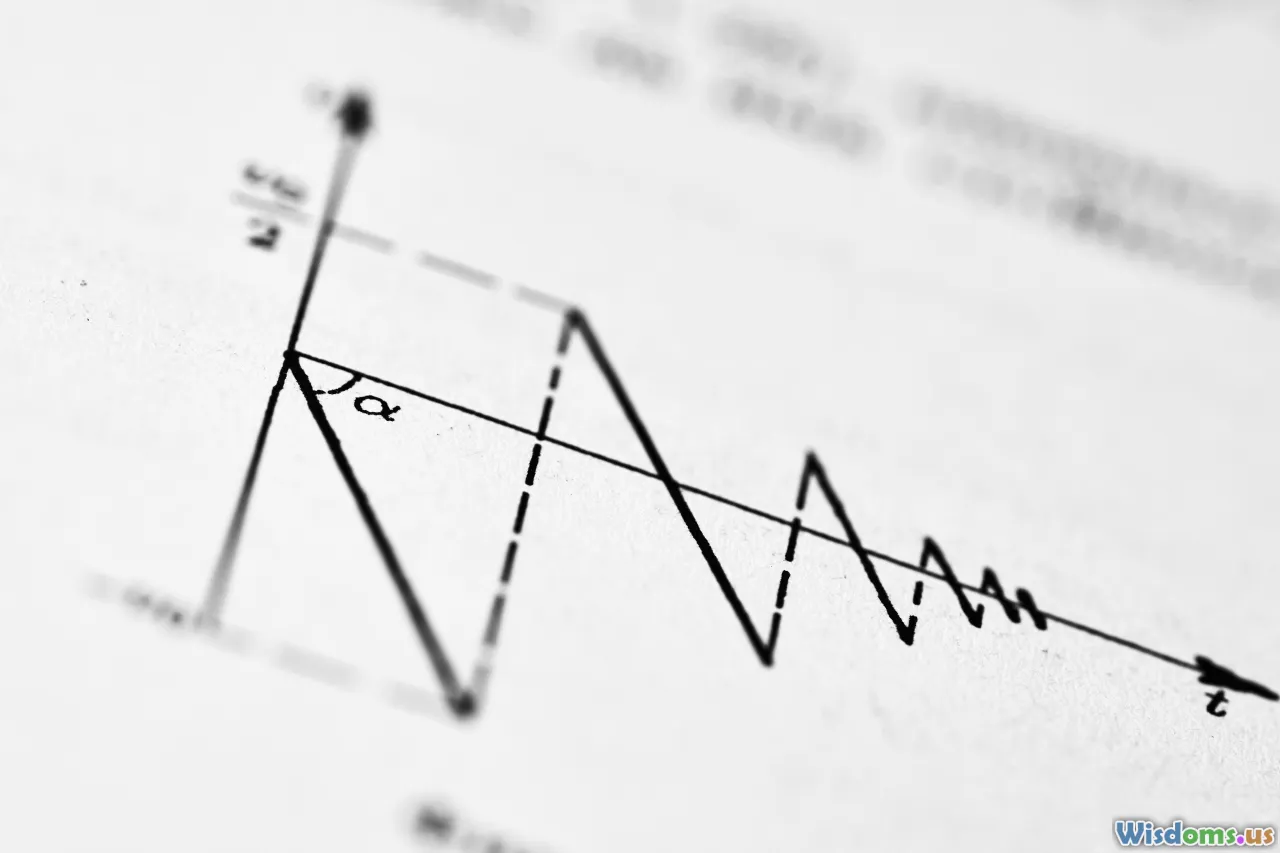

- AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve): Ranges from 0.5 (chance) to 1.0 (perfect). Many well-validated risk tools for violent recidivism sit around 0.65–0.75; personality components alone often live in the lower end of that range.

- Sensitivity and Specificity: Sensitivity = proportion of true positives correctly flagged. Specificity = proportion of true negatives correctly cleared. There’s a trade-off; moving your cutoff increases one and reduces the other.

- PPV/NPV (Positive/Negative Predictive Value): What users really feel. PPV answers, “If I flag someone, what’s the chance I’m correct?” These depend heavily on base rates.

A base rate example: Suppose your jurisdiction’s two-year violent recidivism rate is 10%. A personality-based flagging rule yields 70% sensitivity and 70% specificity (roughly consistent with AUC ≈ 0.70 for an illustrative threshold).

- Out of 1,000 people, 100 will reoffend. You catch 70 of them (sensitivity).

- Of the 900 who won’t, you falsely flag 270 (30% of 900) because your specificity is 70%.

- PPV = 70 / (70 + 270) ≈ 20.6%.

Interpretation: Only about 1 in 5 flagged people actually reoffend violently. With low base rates, even decent tests produce many false positives. That’s not a failure; it’s math. It also shows why decisions should never rest on a single score.

Tests Often Cited in Forensic Contexts

- PCL-R (Psychopathy Checklist–Revised): A clinician-rated instrument based on file review and interview. It includes facets like interpersonal manipulation, callousness, and lifestyle instability. It tends to predict violent recidivism at modest-to-moderate levels (AUCs often around 0.65–0.70 in meta-analyses), especially when rated carefully. It’s not a self-report and requires training.

- MMPI-2-RF/MMPI-3: Broad psychopathology measures with validity scales to detect inconsistent or deceptive responding. Certain scales (e.g., Antisocial Behavior, Behavioral/Externalizing Dysfunction, or the older Pd) are associated with rule-breaking and aggression, but the MMPI is not a crime predictor per se. Under U.S. law, using MMPI for hiring has been found to constitute a medical exam (Karraker v. Rent-A-Center, 2005), raising ADA concerns.

- PAI (Personality Assessment Inventory): Includes Antisocial Features (ANT), Aggression (AGG), and Negative Relationship scales, with built-in validity indicators. Useful in clinical/forensic assessment for contextualizing risk alongside case history.

- Triarchic Psychopathy Measures: Assess boldness, meanness, and disinhibition. Disinhibition and meanness relate more directly to externalizing behaviors; boldness shows complex relations (can track leadership in prosocial contexts).

Important caveat: These instruments measure traits associated with risk. They are not substitutes for comprehensive, structured risk assessments (e.g., HCR-20, LSI-R, or jurisdiction-specific tools) that integrate historical, clinical, and situational factors.

The Power and Limits of Personality Alone

Where personality helps:

- Clarifying risk style: Is the person more impulsive/reactive (heat-of-the-moment) or predatory/instrumental (planned, callous)? This affects supervision and intervention.

- Treatment planning: Low conscientiousness and high disinhibition suggest benefits from structured routines, contingency management, and skills training.

- Communication and compliance: Low agreeableness may require more motivational interviewing and clear, enforceable contingencies.

Where it falls short:

- It underestimates context: Neighborhood factors, peer group, substance access, and acute stressors often drive behavior more than trait differences in the short term.

- It blurs base rates: A high-risk personality profile in a low-risk environment can be safer than a moderate-risk profile in a high-risk environment.

- It can be faked: Self-report measures are vulnerable to socially desirable responding. Validity scales help but don’t eliminate the issue.

Bottom line: Personality contributes a slice of the predictive pie. In most applications, that slice is meaningful but not decisive.

Failure Modes: Faking, Situational Drift, and Group-to-Individual Errors

- Impression management and malingering: People can “fake good” (minimize issues) or “fake bad” (exaggerate problems). Instruments like the MMPI and PAI include validity scales (e.g., L, F, K on MMPI; NIM, PIM on PAI) to flag response distortion. Even so, sophisticated respondents can sometimes evade detection.

- Developmental change: Antisocial behavior peaks in late adolescence/early adulthood and declines with age for most. Personality-related risk tends to soften over time, especially disinhibition and aggression. This means time since last offense and age matter—a lot.

- Cultural and language effects: Items may not carry the same meaning across cultures. Without evidence of measurement invariance, cross-group comparisons risk bias.

- The ecological fallacy: Group-level correlations don’t translate neatly to individuals. Just because a trait predicts higher average risk in a population does not mean a particular person with that trait is dangerous.

- Over-reliance on high-stakes cutoffs: Using a single cutoff score to make liberty- or livelihood-affecting decisions invites error, especially with low base rates.

Practical mitigation: Combine personality data with structured history, check validity indicators, adjust for age and context, avoid hard thresholds, and document reasoning.

Algorithms, Risk Tools, and the Bias Debate

In many jurisdictions, risk assessment tools (e.g., COMPAS, LSI-R, PSA) inform bail, sentencing, and supervision. These tools typically incorporate criminal history, age, employment, substance misuse, and sometimes attitudinal/personality-like items.

- Performance: Many tools achieve AUCs in the 0.65–0.75 range for general or violent recidivism. Personality-like items provide marginal gains beyond robust historical predictors.

- Bias controversy: Analyses of COMPAS flagged higher false-positive rates for Black defendants despite similar overall accuracy to White defendants. The debate centers on competing fairness definitions—equal accuracy vs. equal error rates vs. calibration. No single tool can satisfy all fairness criteria simultaneously when base rates differ across groups.

- Transparency: Black-box models hinder scrutiny. Open, interpretable tools with published validation (including subgroup analyses) are preferable in high-stakes contexts.

Implication for personality measures: If attitudinal or trait items are included, stakeholders must ensure they operate equivalently across groups and do not merely proxy for socioeconomic disadvantages.

When Personality-Based Prediction Adds Value

- Corrections and supervision planning: A client high on impulsivity may benefit from weekly check-ins, contingency management, and relapse prevention. A client high on callousness may require tighter monitoring around victims and high-risk associates.

- Violence risk formulation: Personality informs whether risk is driven by grievance, thrill-seeking, psychosis, or opportunity. Interventions differ accordingly.

- Rehabilitation matching: Traits guide the intensity and style of cognitive-behavioral programs—for instance, more skills rehearsal for low conscientiousness; empathy and perspective-taking exercises for callous traits.

Notable boundary: Personality is much better at informing how to manage risk than at deciding whether to detain or hire. It’s a compass for supervision and treatment, not a gatekeeper by itself.

What Not to Do: Misuse in Employment and Screening

- Don’t use clinical personality tests (e.g., MMPI) in routine hiring. U.S. courts have deemed the MMPI a medical exam; using it for non-medical employment decisions can violate the ADA (Karraker v. Rent-A-Center, 2005). The EEOC also scrutinizes practices with disparate impact under Title VII.

- Don’t market “crime prediction” to employers. Predicting criminal acts from personality for pre-employment screening is ethically fraught and likely illegal or noncompliant in many jurisdictions.

- Don’t ignore privacy rules. Psychometric data can be sensitive. GDPR and similar laws require clear consent, purpose limitation, and data minimization.

- Don’t label individuals as “high risk” without context and due process. Overbroad flags can stigmatize, reduce opportunities, and become self-fulfilling.

Instead: Fit-for-role assessments should focus on job-relevant competencies, validated for that role, with documentation of fairness and predictive validity for job performance and misconduct outcomes, not criminality.

How to Use Personality Evidence Responsibly (Step-by-Step)

-

Clarify the decision. Are you managing supervision intensity, planning treatment, or informing a broader risk assessment? Personality evidence is most useful for tailoring interventions.

-

Choose the right instrument. Use validated tools with evidence in similar populations. For forensic settings, consider instruments with validity scales and strong manuals.

-

Verify conditions and validity. Ensure proper instructions, language competence, and absence of coercion that could drive faking. Check validity indicators and response consistency.

-

Integrate context. Combine test scores with structured history (age at first offense, prior convictions, substance issues), current stressors, supports, and environmental risks.

-

Translate traits into management targets. For example:

- Low conscientiousness → tight schedules, checklists, incentives for adherence.

- High disinhibition → impulse control training, contingency management, hotspot monitoring.

- High antagonism → communication scripts, clear boundaries, conflict de-escalation plans.

-

Avoid single-score thresholds. Use multiple converging indicators and explain the rationale in plain language.

-

Reassess. Risk is dynamic. Review at meaningful intervals or after material changes (new charges, job loss, relationship changes).

-

Document ethically. Record what was measured, how, limitations, and how results informed decisions—and what safeguards are in place to avoid undue harm.

Comparing Prediction Targets: Onset, Persistence, and Recidivism

- Onset (first-time offending): Often influenced by peer exposure, opportunity, and adolescent impulsivity. Personality can signal vulnerability (e.g., sensation seeking), but opportunities and supervision matter enormously.

- Persistence/Chronic offending: Stronger links with traits like disinhibition, callousness, and hostile attribution bias, combined with entrenched life problems (substance dependence, unstable housing).

- Recidivism: Best predicted by a blend of historical factors (past behavior), age, and dynamic criminogenic needs. Personality adds nuance about triggers and management but rarely outperforms prior behavior as a predictor.

In practice: A 19-year-old with high sensation seeking and peers engaged in theft poses a different profile from a 35-year-old with callous-unemotional traits and a history of violent assaults. Personality helps differentiate mechanisms and tailor interventions.

Cross-Cultural and Developmental Considerations

- Measurement invariance: Ensure the test has been validated for your specific population and language. Without this, scores may reflect cultural response patterns rather than true trait differences.

- Age gradients: Expect lower externalizing risk with age for most individuals, independent of personality scores. Don’t over-interpret a stable trait when base behavioral risk is naturally declining.

- Gender differences: Some traits manifest differently by gender, and base rates for certain offenses differ. Validation should report subgroup performance, not just overall accuracy.

Action tip: Before adopting a tool, demand subgroup AUCs, calibration plots, and error rate breakdowns. If a vendor can’t provide them, reconsider.

A Closer Look at Psychopathy: Sharp Signal, Serious Caveats

Psychopathy is the most studied personality construct in violence risk. High scores are associated with increased likelihood of violent and general recidivism and poor treatment response in some settings.

Caveats:

- Not all psychopathy measures are equal. Clinician-rated tools using multiple data sources outperform brief self-reports.

- High scores are neither necessary nor sufficient for violence. Many violent offenders do not score high on psychopathy, and some individuals with psychopathic traits avoid criminal behavior due to strong incentives, oversight, or prosocial channels for risk-taking.

- Stigmatizing labels can harm. Focus on specific behavioral risks (e.g., “low empathy and poor impulse control in conflict”) rather than global labels.

Practical use: If an assessment indicates high meanness and disinhibition, supervision should prioritize victim safety planning, reduce access to weapons, and place limits on unsupervised contact in high-conflict settings. Treatment may emphasize empathy-building, problem-solving, and accountability structures.

From Scores to Strategy: Turning Data into Decisions

A useful way to operationalize personality findings is to map them to concrete controls and supports. For example:

- Trigger mapping: Identify situations where traits are likely to surface (e.g., payday drinking, relationship conflicts). Plan alternatives and buffers.

- Incentive design: For low conscientiousness, build small, frequent rewards for adherence rather than large, delayed rewards.

- Communication frameworks: With high antagonism, use brief, behavioral language: describe the behavior, state the impact, set a clear contingency.

- Environmental leverage: Place the person in roles or routines that channel sensation seeking into prosocial challenges (sports, timed tasks) and reduce idle time.

Integrate these with standard risk-reduction elements: substance use treatment where indicated, employment support, prosocial peer engagement, and problem-solving training.

Two Mini Case Studies

Case A: Probation planning for a 24-year-old with assault charges

- Profile: Low agreeableness, low conscientiousness, high disinhibition; valid responding. History of bar fights, binge drinking, unemployed.

- Risk formulation: Reactive aggression when intoxicated; poor routine; antagonistic when criticized.

- Plan:

- Weekly probation check-ins; random alcohol tests.

- Enroll in CBT focusing on emotion regulation and problem-solving.

- Contingency management: immediate rewards for consecutive weeks of compliance.

- Employment assistance aimed at structured jobs with clear tasks and supervision.

- Expected effect: Reduced exposure to triggers, improved impulse control, clear incentives for prosocial routine.

Case B: Corporate misconception about “screening out criminals”

- Scenario: A retailer considers a low-cost online personality test claiming to flag theft risk.

- Issues:

- No published validation for theft prediction in retail; likely adverse impact.

- Self-report only; easy to fake; no validity scales.

- Potential ADA/EEOC problems if items tap clinical constructs.

- Advice:

- Focus on structured interviews, integrity tests with published fairness data, reference checks, inventory controls, and loss-prevention procedures.

- Use personality only for job-relevant traits (e.g., reliability, teamwork), with local validation and privacy safeguards.

Outcome lesson: Responsible risk reduction comes from systems and supervision, not a single score.

Practical Tips by Role

For clinicians and probation officers:

- Use personality to tailor interventions, not to label. Write formulations that connect traits to specific behaviors and triggers.

- Double-check validity indicators and context before drawing conclusions.

- Consider modular programs: impulse control modules for disinhibition; empathy exercises for callous traits.

For courts and policy makers:

- Require transparency: validation studies, subgroup performance, calibration, and error rates for any tool used in decisions affecting liberty.

- Pair assessments with resources: Treatment availability and supervision capacity determine whether risk information matters.

- Avoid over-precision: Express results probabilistically, with ranges and caveats.

For employers and HR leaders:

- Keep to job relevance. Validate assessments for performance and turnover, not criminality.

- Minimize sensitive data. Favor short, work-specific measures; provide clear consent and opt-outs.

- Measure outcomes. If you use an assessment, track whether it actually reduces misconduct and improves performance without disparate impact.

For researchers and vendors:

- Publish subgroup metrics and pre-register validation plans.

- Test measurement invariance across languages and cultures.

- Explore hybrid models that blend traits with dynamic risk factors—and report calibration, not just discrimination.

Common Questions, Answered

- Can a high psychopathy score “prove” someone will commit a crime? No. It indicates elevated risk and informs management but cannot determine individual outcomes.

- Are Big Five scores enough to predict theft or violence at work? Not reliably. They add small, incremental signal; controls and culture matter more.

- Do people just fake these tests? Some try. Validity scales detect many patterns, but not all. Multi-method assessment reduces this risk.

- Are algorithmic tools fair? They can be calibrated overall yet still produce uneven error rates across groups. Fairness requires ongoing monitoring, transparency, and, often, policy choices about acceptable trade-offs.

- Should I ever use a cutoff score to deny a job or release? Not based on personality alone. If a cutoff is used in a composite risk tool, it should be part of a broader process with human review and documented safeguards.

What the Future Might Bring—and What It Shouldn’t

Emerging directions include digital phenotyping (behavioral traces from devices), adaptive testing, and integration with ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to capture state fluctuations like stress or intoxication in real time. These may improve short-term risk monitoring by capturing context better than static trait measures.

Yet caution is paramount:

- Privacy: Passive data collection raises serious consent and surveillance concerns.

- Bias amplification: Models trained on historical data can inherit and magnify existing disparities.

- Overfitting: Complex models may look good in development and fail in the field. External validation is non-negotiable.

A responsible future pairs innovation with guardrails: clear use cases, minimal data necessary, opt-in consent, robust validation, independent audits, and avenues for contesting decisions.

Bringing It Together: A Sober, Useful Answer

So, can personality tests predict criminal behavior? Here’s the sober answer:

- They predict on average, not deterministically. Certain traits—low conscientiousness, low agreeableness, high disinhibition, callousness—carry modest risk signals for antisocial and violent outcomes.

- They work best as part of a broader risk formulation. Combine traits with history, current stressors, and protective factors. Expect AUCs in the modest range; rely on calibration and context to guide decisions.

- They’re far better for management than selection. Use them to tailor supervision, treatment, and communication strategies—not to greenlight or blacklist individuals.

- Ethics and legality matter. Avoid clinical tests in routine hiring, guard privacy, check subgroup validity, and document limitations.

A final practical takeaway: If you must summarize the role of personality in criminal risk in a single sentence, make it this—personality tests can illuminate the pathways by which risk might unfold, but only systems, supports, and context determine whether it actually does.

And that’s the shift from the drama of prediction to the real work of prevention.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts