Why Eyewitness Testimony Is Not Always Reliable in Court

8 min read Explore why eyewitness testimony often falters in court despite its intuitive appeal. (0 Reviews)

Why Eyewitness Testimony Is Not Always Reliable in Court

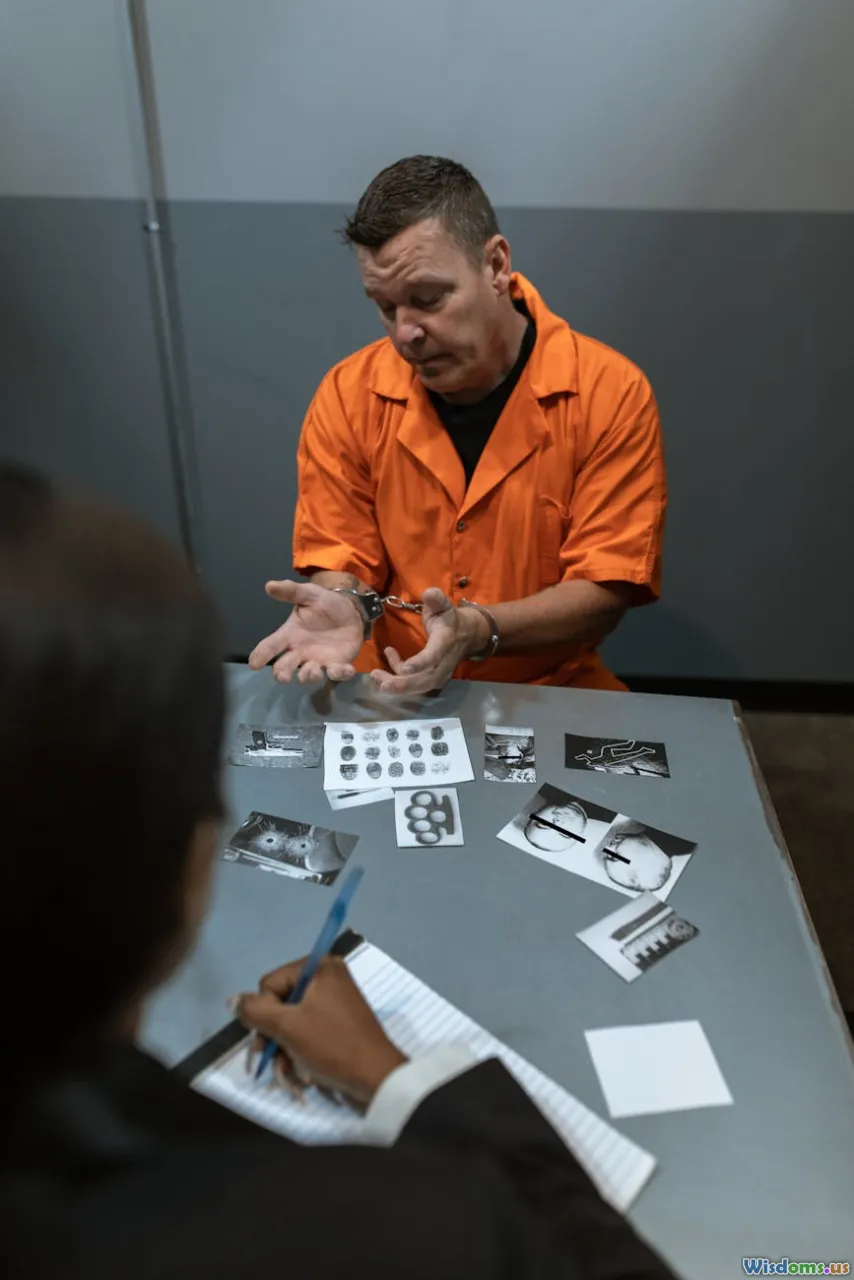

Eyewitness testimony has historically held a revered position in legal systems worldwide. After all, a witness who personally observed a crime seems like the ideal source for confirming what truly happened. However, beneath this seemingly straightforward reliance lies a complex web of psychological and situational factors that often render eyewitness accounts unreliable. This article unpacks the science behind these limitations, examines landmark court cases, and analyzes how cognitive biases and memory distortions undermine the justice process.

The Illusion of Perfect Recall

Memory Is Not a Video Recorder

One of the most common misconceptions is the belief that human memory works like a perfect video tape, capturing and storing life events in flawless detail. Cognitive psychology demonstrates otherwise. Memories are dynamic and reconstructive. When witnesses recall an event, they are actually piecing together fragments influenced by their emotions, existing beliefs, and subsequent information.

Elizabeth Loftus, a prominent psychologist, has extensively studied false memories and eyewitness reliability. A famous experiment by Loftus involved participants witnessing a simulated car accident and then being questioned about details like the speed of the vehicles. When the phrasing of questions changed subtly — for example, "How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?" versus "hit each other?" — participants' speed estimates and recollections significantly differed. This research highlights how even subtle external influences can weave confabulated details into memory.

Stress and Trauma Distort Perception

Legal situations involving serious crimes—robberies, assaults, murders—often place witnesses under high stress. While intuition suggests that traumatic stress would sharpen memory, scientific evidence tells a different story.

Under acute stress, the brain’s amygdala is activated, altering the encoding of memories. Witnesses might fixate on a weapon due to "weapon focus" effect, neglecting other important details like the perpetrator’s face or clothing. For example, a study published in Law and Human Behavior found that witnesses under weapon focus conditions had significantly reduced accuracy in recalling peripheral details.

Furthermore, extreme fear or anxiety may impair the consolidation of memory, leading to fragmented or spotty recollections.

Cases Exposing Eyewitness Errors

The Central Park Five

One of the most striking modern examples is the wrongful conviction of the Central Park Five in 1989. Five teenagers were convicted largely based on eyewitness statements and coerced confessions regarding the assault and rape of a jogger in New York City’s Central Park.

Years later, DNA evidence and the confession of the actual perpetrator exonerated them. The case underscored how eyewitnesses and even victims can unintentionally identify incorrect suspects, influenced by stress, bias, or social pressure.

Ronald Cotton Case

In 1984, Jennifer Thompson was raped and later identified Ronald Cotton as her attacker during a lineup. Despite her confident testimony, DNA evidence exonerated Cotton over a decade later. This highlighted how even confident eyewitnesses had difficulty accurately identifying suspects, especially during high-stress events.

Thompson herself admitted that her memory was flawed, stating, “My memory convinced me it had to be Ronald… I was not lying; I was sincerely wrong.”

Cognitive and Social Influences on Eyewitness Testimony

The Role of Suggestibility

Eyewitness memories can be highly suggestible. Law enforcement’s line of questioning, media reports, or discussions among witnesses can all inadvertently implant false details.

For instance, when witnesses discuss events with one another before recording statements, they may inadvertently adopt memories from others—a phenomenon called memory conformity.

An FBI survey cites that badly constructed interrogative procedures can lead to fabricated or altered memories, compromising testimony integrity.

Cross-Racial Identification Challenges

Research consistently shows that people are generally less accurate at identifying individuals of races different from their own.

This cross-race effect means that interracial identifications are more prone to error. A meta-analysis by Meissner and Brigham (2001) showed that individuals were about 1.5 times more likely to misidentify someone of another race.

Many wrongful convictions have hinged on this phenomenon.

The Passage of Time and Memory Decay

Time further erodes accuracy. With longer delays between witnessing an event and testifying, memories weaken and may become distorted.

The Innocence Project reports that in over 70% of DNA-exoneration cases, eyewitness misidentification was involved, often correlating with long time lapses before testimony.

Improving Eyewitness Reliability

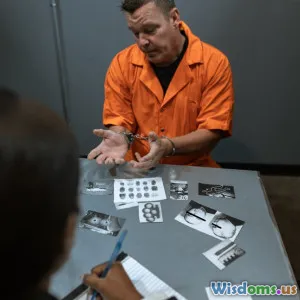

Enhanced Police Procedures

Recognizing these pitfalls, reform initiatives emphasize better lineup techniques. Double-blind lineups, where the officer conducting the lineup does not know the suspect’s identity, decrease unintentional influence.

Using sequential (one-by-one) rather than simultaneous lineups helps witnesses avoid comparative judgments, which can lead to false identifications.

Expert Testimony

Courts increasingly allow psychological experts to educate juries about the limitations and nuances of eyewitness testimony. Providing this context helps counter the undue weight jurors might assign to confident but inaccurate eyewitnesses.

Technological Advances

The integration of body cameras, surveillance footage, and other objective evidence aids corroboration of eyewitness accounts, reducing sole reliance on human memory.

Juror Education and Instructions

Clear judicial instructions reminding jurors of the potential shortcomings of eyewitness identification have been shown to improve verdict accuracy.

Conclusion: Proceed with Caution

While eyewitness testimony remains a powerful and sometimes necessary component of legal processes, it is far from infallible. Scientific research, case histories, and evolving legal standards reveal the vulnerabilities inherent in human memory and perception.

Understanding these weaknesses helps promote more cautious, evidence-based legal decisions and drives reform in investigative and courtroom practices.

Injustice born out of misplaced confidence in eyewitness testimony can ruin lives. Legal professionals, jurors, and society must recognize that memory is a living, fallible process—not an unerring recorder—to foster a more just system.

References

- Loftus, E. F. (1975). Leading questions and the eyewitness report. Cognitive Psychology, 7(4), 560-572.

- Innocence Project. (n.d.). Eyewitness Misidentification.

- Meissner, C. A., & Brigham, J. C. (2001). Thirty years of investigating the own-race bias in memory for faces: A meta-analytic review. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 7(1), 3–35.

- Wells, G. L., et al. (1998). Eyewitness identification procedures: Recommendations for lineups and photospreads. Law and Human Behavior, 22(6), 603–647.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts