The Science Behind Eyewitness Testimony Errors

33 min read Explore the cognitive science behind eyewitness errors, from stress and attention to lineups, and learn evidence-based practices that reduce wrongful convictions. (0 Reviews)

You remember the face clearly—sharp jawline, a hoodie, eyes that wouldn’t meet yours. You hear yourself saying, “I’m sure.” Hours later, the certainty fades. Days later, the lineup happens, and a stranger starts to look familiar. Months later, your memory and your confidence are paraded before a jury. The science of eyewitness memory explains how each of those steps, perfectly human and often well-intentioned, can bend a recollection out of shape.

This article explores why eyewitnesses—good people trying their best—can make serious mistakes. We’ll unpack the psychology of memory, show how stress and suggestion alter recall, and translate decades of research into practical steps for investigators, judges, jurors, and even everyday citizens who might one day have to describe what they saw.

Memory Is Not a Video Recorder: How Recall Really Works

Memory feels like playback. In reality, it’s reconstruction. When you see an event, your brain doesn’t store a perfect file; it encodes fragments—shapes, sounds, meanings, feelings—then rebuilds them later using prior knowledge and context. That later reconstruction can be astonishingly accurate, or it can be quietly wrong in ways that matter.

Consider three key stages:

- Encoding: You take in information while your attention competes with noise, motion, lighting, and your own stress level.

- Storage: Memories consolidate. With time, details fade or blend with other experiences. Sleep helps, but so do repeated exposures—helpful when correct, harmful when the exposures are misleading.

- Retrieval: You rebuild the memory using cues, expectations, and questions asked. Each retrieval can slightly alter the memory itself.

Three concepts ground the science:

- Reconstructive memory: We use schemas—mental frameworks about how the world works—to fill gaps. If you expect a convenience store robber to wear a ski mask, later you might “remember” a mask when there wasn’t one.

- Gist vs. verbatim: Fuzzy-trace theory suggests we store the general meaning (gist) and some exact details (verbatim). With time, gist survives better than verbatim. You may recall “a dark sedan” rather than “a 2012 black Toyota Camry with a cracked right tail light.”

- Interference: New information overwrites or blends with old memories. If you discuss the crime with another witness, you risk importing their details into your own recollection.

Research offers striking examples. In the DRM (Deese–Roediger–McDermott) paradigm, people hear lists of words like bed, rest, awake, dream—but not the word sleep. Later, most “remember” sleep as being on the list with strong confidence. This isn’t deception; it’s how associative memory works.

What this means for eyewitnesses: even when a person is honest and confident, their mind may sew a coherent tapestry out of incomplete threads. It feels right. It may be wrong.

Stress, Arousal, and the Weapon Focus Effect

High stress narrows attention. In violent crimes, witnesses often fixate on the most threatening element—the weapon—at the cost of peripheral detail. This weapon focus effect is robust: when a gun appears, observers’ memory for the assailant’s face reliably declines compared to similar events without a weapon.

Why? Under acute stress, the body floods with adrenaline and cortisol. These hormones sharpen certain responses (like vigilance) while impairing others (like encoding fine details of faces). The Yerkes–Dodson law captures the idea that performance rises with arousal to a point, then falls—you’re alert enough to stay alive, but too stressed to encode nuance.

Practical example: Two convenience store robberies occur minutes apart. In Store A, the robber gestures under a jacket, implying a weapon; in Store B, the robber displays a handgun. Witnesses in Store B later provide fewer accurate descriptors of the robber’s face, despite feeling more confident in their memory. This is not because they care less; it’s because fear hijacked their attention.

Key takeaways:

- Threat pulls the eye. Accuracy for central threat features may rise, while peripheral memory (faces, clothing colors, license plates) suffers.

- Stress impacts are strongest during encoding. Later calm cannot restore details that were never encoded.

- Training can improve observational strategies for professionals, but civilians under sudden threat remain vulnerable to attentional narrowing.

The Misinformation Effect and How Memory Gets Rewritten

Language and suggestion alter memory. Classic experiments show that asking, “How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” produces higher speed estimates than “bumped.” Later, participants are more likely to “remember” broken glass that never existed. The wording injects expectation.

In the wild, misinformation seeps in through many doorways:

- Leading questions: “He had a scar on his left cheek, right?” plants a detail.

- Media exposure: News photos, social posts, or surveillance stills viewed after the event can blur with memory. If a witness sees a suspect’s photo repeatedly, familiarity alone can feel like recognition.

- Co-witness conversation: “I think he wore a red cap,” says one. “Yes, red,” says another, and suddenly both “remember” red.

- Repeated interviews: Each retelling risks small edits that harden over time.

Source monitoring errors are the culprit: people conflate where a detail came from—saw it at the scene, or read it online? A witness may be certain the memory is firsthand when it’s secondhand.

Actionable advice:

- Investigators should record interviews, ask open-ended questions, and avoid introducing specifics unless necessary.

- Witnesses should write their account immediately, then avoid media or discussion about the event until official interviews conclude.

- Courts should scrutinize whether post-event information might have polluted recall.

Cross-Race Identification: The Other-Race Effect

People generally recognize faces of their own racial or ethnic group more accurately than those of other groups. This other-race effect is well-documented across countries and decades. It arises from a mix of perceptual expertise (we learn distinctive cues by seeing similar faces frequently) and social-cognitive factors (attention and motivation).

In practice, cross-race identifications are riskier. Jurors must resist assuming that sincere confidence equals accuracy when the identification crosses racial lines. For law enforcement, lineup construction becomes even more critical:

- Fillers (non-suspects) must match the witness’s description, especially on race and salient features, so the suspect doesn’t stand out.

- Pre-lineup instructions should explicitly state that the perpetrator may not be present.

- Consider expert testimony to educate jurors about the other-race effect when relevant.

A concrete example: A witness describes “an Asian male with short hair and thin eyebrows.” The lineup includes an Asian suspect and five fillers who are white or have notably different hair or eyebrow thickness. The suspect becomes the only plausible choice. Even a careful witness may feel the lineup “proves” their memory. In truth, the lineup is biased.

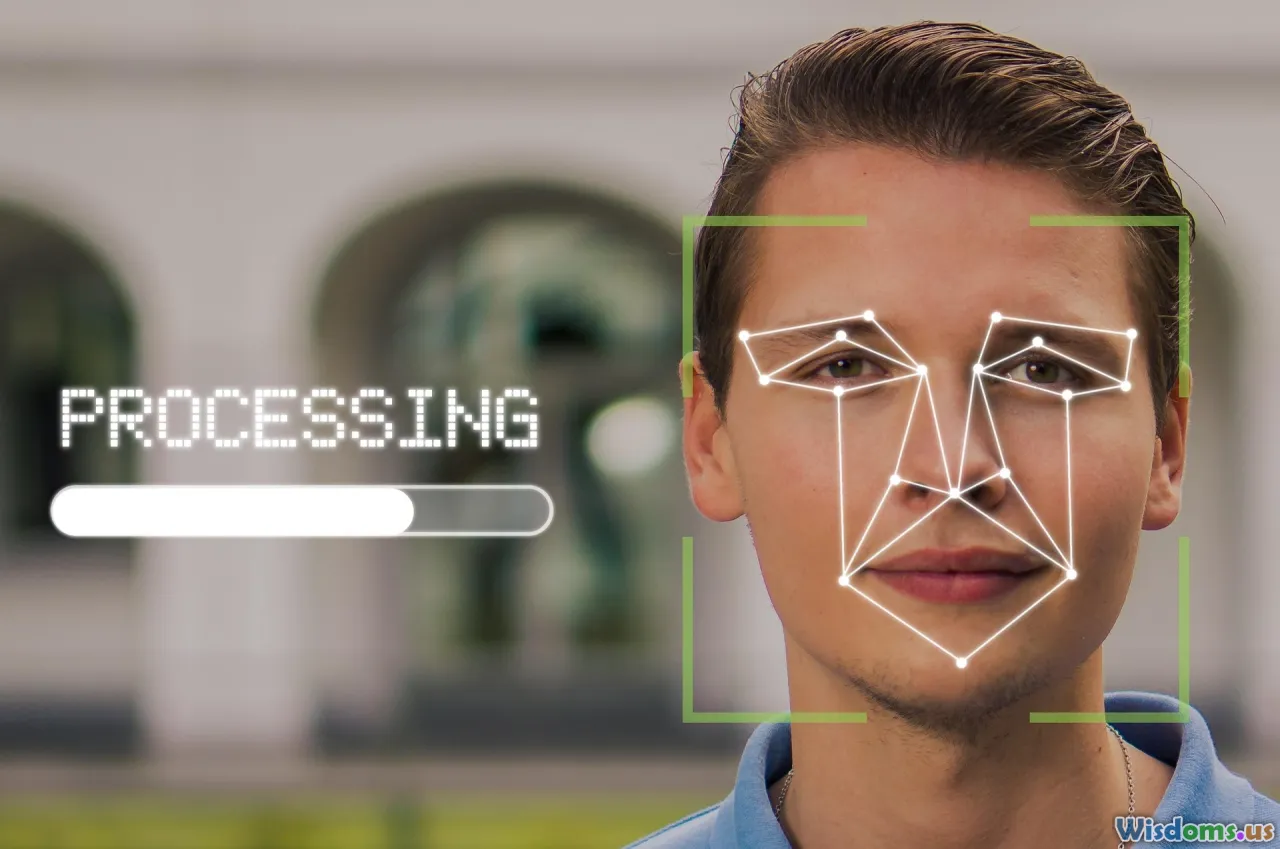

Show-Ups, Lineups, and Photo Arrays: Procedure Matters

How police present choices shapes decisions. Identification procedures fall along a spectrum of risk:

- Show-ups: The witness views a single person—often near the scene—shortly after the crime. Show-ups are fast and sometimes necessary, but they are inherently suggestive.

- Photo arrays: The witness views a set of photos containing one suspect and several fillers.

- Live lineups: Similar to arrays but with people in person.

A central distinction in the science is between estimator variables (factors tied to the event, like lighting and stress, which the system can’t control) and system variables (factors tied to police procedure, like instructions and lineup composition, which are controllable). System variables can be optimized:

- Double-blind administration: The person running the lineup does not know who the suspect is, preventing subtle cues—like tone or body language—that nudge the witness.

- Proper fillers: Choose fillers that match the witness’s description, not the suspect’s favorite mugshot. Fillers should be plausible to reduce the chance that the suspect stands out.

- Clear instructions: Explicitly say the perpetrator may or may not be in the lineup; the investigation will continue regardless of selection.

- Sequential vs. simultaneous: Sequential lineups show photos one at a time; simultaneous show all at once. Sequential can reduce relative-judgment errors (“who looks most like the guy?”) but can also reduce correct IDs in some contexts. Researchers debate which is best; jurisdictions should choose evidence-based protocols and monitor outcomes.

- Immediate confidence statement: Capture the witness’s confidence verbatim at the moment of identification, before any feedback.

- Avoid repeated identifications: Seeing the same suspect across multiple procedures fosters familiarity that feels like recognition.

Real-world risk: If an officer says, “Good, you picked the same guy as the other witness,” the witness’s confidence can skyrocket without any change in underlying accuracy. That feedback contaminates both memory and court testimony.

Confidence and Accuracy: When Do They Align?

Confidence is tricky. Many assume that a very confident witness is a very accurate witness. The research says: it depends.

Under pristine conditions—proper lineup, good instructions, no feedback—initial confidence is meaningfully related to accuracy. A witness who immediately says, “I’m 90% sure” tends to be more accurate than one who says, “I’m 50% sure.” But once suggestion or feedback enters, confidence can inflate independent of accuracy.

Key points for courts:

- Initial confidence matters most. Capture it at the moment of identification and document the exact words.

- Post-identification feedback (even unintentional) boosts confidence without improving accuracy. Later confidence—days, weeks, or months afterward—may be a poor signal.

- Calibration curves reveal that low-confidence IDs are often unreliable and high-confidence IDs can be informative only when the procedure was fair.

- Beware in-court identifications. Seeing the defendant seated at counsel table after months of exposure powerfully biases recognition.

Practical application: Judges can allow expert testimony to explain the confidence–accuracy relationship and instruct jurors to weigh initial statements more heavily than polished courtroom certainty.

Children, Older Adults, and Vulnerable Witnesses

Age affects memory in distinct ways. Children, especially young ones, can recall central events but are more suggestible; they are more prone to accept leading questions and to blend details from repeated interviews. Older adults can have strong gist memory but may show declines in source monitoring and face recognition, especially under stress or distraction.

Tips for interviewing vulnerable witnesses:

- Build rapport and use open-ended prompts: “Tell me everything you remember,” rather than “Was the jacket blue?”

- Avoid repetition. Each new interview should draw from the witness’s own earlier account rather than reintroducing new details.

- Break long sessions into shorter, child- or age-appropriate segments.

- For older adults, reduce distractions, ensure good lighting and audibility, and allow more time for retrieval.

- Use trained forensic interviewers for children, following structured protocols that minimize suggestibility.

The right technique often helps vulnerable witnesses provide reliable information while respecting their limits and dignity.

Lighting, Distance, and Duration: The Physics of Seeing

Your eyes impose hard limits. Under ideal conditions, 20/20 vision resolves about one arcminute—roughly the ability to distinguish a 4–5 millimeter detail at 15 meters. Crime scenes are rarely ideal.

Consider the trio that matters most:

- Lighting: At night, human vision shifts toward scotopic (rod-dominated) vision, which excels at motion detection but sacrifices color and fine detail. Sodium-vapor streetlights distort color. Backlighting silhouettes faces. Strobing police lights create motion artifacts.

- Distance: Facial recognition plummets with distance. Beyond 15–20 meters in poor light, even large facial features can blur together.

- Duration: Seconds count. A 2-second face view while ducking behind a car is not the same as a minute-long, stationary interaction.

Practical heuristics:

- If the scene involved rapid motion and dim light, expect weaker facial memory, especially for unfamiliar faces.

- Clear, stationary views under good light for 10–15 seconds dramatically improve recognition odds.

- Obstructions—hats, masks, glasses—slice away diagnostic features. During the pandemic, mask-wearing made eyewitness face ID particularly challenging; eyebrows and eye shape became more critical cues.

These physics aren’t opinions; they are constraints. Good procedures respect them.

Memory Contamination in the Justice Pipeline

Memory gathers contaminants the way a white shirt collects stains. Common culprits include:

- Composite sketches: Asking a witness to build a face piece-by-piece can shift memory toward the composite rather than the original person.

- Mugshot exposure: If a witness scans many photos pre-lineup, suspects seen earlier may feel “right” later. This is unconscious transference—misplacing familiarity.

- Confirming feedback: “That’s who we thought it was.” Even a smile can do it.

- Co-witness contamination: Shared narratives become shared certainties.

- Multiple procedures: A show-up followed by a photo array followed by a lineup turns familiarity into false confidence.

Systems-level fixes:

- Record the entire identification procedure on video. Transparency deters suggestiveness and helps courts evaluate fairness.

- Keep a clean separation between investigative theories and witness memory work. Don’t use the witness to confirm what the case file already presumes.

- Maintain a record of all photos or lineups a witness has seen; courts should know the exposure history.

The Cognitive Interview: A How-To for Better Memory Retrieval

The cognitive interview is an evidence-based method that enhances recall without introducing new information. It hinges on reinstating context and giving control back to the witness.

Step-by-step guide:

- Build rapport. A calm, respectful tone reduces anxiety and fosters detailed recall.

- Explain the process. Emphasize that guesses are discouraged and “I don’t know” is acceptable.

- Context reinstatement. Ask the witness to mentally return to the scene—what they saw, heard, smelled, and felt. Environmental details serve as retrieval cues.

- Open-ended narrative. Invite a free recall: “Tell me everything from the beginning to end.” Do not interrupt; let silences work.

- Varied recall. After the initial account, ask the witness to retell the story in a different order (e.g., backwards) or from a different vantage point (e.g., “imagine you were across the street”). This can cue additional, accurate details without leading.

- Witness-compatible questioning. Tailor follow-ups to the witness’s wording. Avoid introducing new concepts; instead, use their terms to probe specific gaps.

- Avoid forced-choice questions. Ask, “What color was the jacket?” not “Was it blue or black?”

- Use nonverbal aids. If appropriate, allow simple sketches or maps to anchor spatial memory.

- Close by summarizing in the witness’s own words. Confirm they agree with the summary and correct any misstatements.

- Document verbatim. Record the session. Capture qualifiers like “I think,” “I’m not sure,” and exact confidence levels.

Used properly, the cognitive interview can increase correct recall significantly while keeping false details in check.

What Technology Helps—and Hurts—Eyewitness Accuracy

Technology is a double-edged lens.

What helps:

- Body-worn cameras and high-quality CCTV preserve objective details—timelines, paths, interactions—that can anchor or correct memory.

- Early scene capture (photos, video) documents lighting, distance, and sightlines, aiding later evaluation of what a witness plausibly could see.

- Digital lineup platforms can enforce double-blind administration, randomize order, and lock in initial confidence statements.

What hurts:

- Social media exposure. Viral images of “suspects” can seed familiarity in witnesses who later feel they “recognize” someone from the crime.

- Low-frame-rate or low-resolution video invites overinterpretation. Blurry footage can create compelling but false certainty when witnesses or jurors fill gaps with expectation.

- Repeated digital exposure. Seeing a face many times online makes it feel known, increasing the risk of misattribution.

Best practice: Treat videos and photos as separate evidence streams. Don’t show a witness a possibly irrelevant video before a formal identification procedure. Use video to corroborate, not to prime memory.

For Investigators: Checklist for Fair Identifications

A practical, research-informed checklist reduces error:

- Use double-blind lineup administration. If impossible, at minimum, prevent the administrator from seeing the screen and script all comments.

- Provide standardized instructions, in writing: “The perpetrator may or may not be present.” Have the witness read and sign.

- Construct fair arrays. Choose fillers using the witness’s description. Pretest by asking independent people, “Who stands out?” Adjust until no one does.

- Prefer single, well-constructed procedures over multiple exposures. Avoid show-ups unless exigent circumstances exist; if you use a show-up, document why.

- Present items sequentially when feasible and do not allow back-and-forth comparison without a controlled process.

- Record. Video the entire procedure, capturing witness and administrator audio and visuals.

- Capture initial confidence verbatim and numerically (e.g., 0–100%). Do not provide feedback.

- Maintain chain-of-custody for all materials, including fillers and instructions, to enable later review.

- Document conditions: lighting, distance, duration, stress indicators, and any post-event exposures known.

For Judges and Jurors: Questions That Cut Through the Fog

Jurors and judges can anchor their evaluation in science by asking:

- How fair was the procedure? Was it double-blind? Were fillers appropriate? Were instructions clear?

- What was the initial confidence, recorded verbatim, and when? Did anyone provide feedback before or after?

- What estimator variables were at play—lighting, distance, duration, stress, disguise?

- Is this a cross-race identification? If so, was the jury educated on the other-race effect?

- Has the witness had prior exposures to the suspect’s face—mugshots, media, prior procedures?

- Is the in-court identification independent, or a product of repeated exposures to the defendant at counsel table?

- Are there corroborating pieces of evidence—DNA, fingerprints, consistent surveillance video—that align with the identification?

A short instruction can help: treat eyewitness identifications like any scientific measurement—evaluate the instrument (the procedure), the conditions (the scene), and the readout (the initial confidence) before relying on the result.

Cognitive Biases: How Expectations Shape What We “See”

Our minds lean on shortcuts that speed decisions but invite error. In eyewitness contexts, three biases loom:

- Confirmation bias: Once an investigator or witness believes a suspect fits, they unconsciously seek supporting details and discount contradictory ones.

- Expectancy effects: Subtle cues from authority figures guide responses—tone, body language, or the phrasing of questions.

- Stereotype-consistent memory: We remember details that fit societal stereotypes more readily than those that don’t, which can distort recall.

Famous demonstrations of attentional limits—like inattentional blindness where observers miss a person in a gorilla suit when focused on counting ball passes—highlight that attention is a narrow spotlight. If you never attended to a face, your “memory” for it later is a guess dressed as recollection.

Mitigations:

- Blinding and scripting reduce expectancy effects.

- Strong record-keeping exposes post-hoc rationalizations.

- Education—through jury instructions or expert testimony—resets overconfident assumptions about memory.

Real Cases, Real Lessons

Eyewitness misidentification is the leading contributor to wrongful convictions proven by DNA in the United States. Analyses of DNA exonerations repeatedly find that roughly 70% involved at least one mistaken eyewitness.

Take the case of Ronald Cotton. In 1984, a North Carolina college student, Jennifer Thompson, was attacked and later identified Cotton as her assailant. She was honest and determined to help. Years later, DNA evidence exonerated Cotton and identified the true perpetrator. Thompson became a prominent advocate for reform, a testament to how good intentions meet fallible memory.

Or consider Kirk Bloodsworth, sentenced to death in Maryland based in part on eyewitness testimony and later exonerated by DNA. The Central Park Five—five teenagers convicted in a 1989 assault—were also exonerated years later after DNA and a confession from the true perpetrator. In each story, witnesses and victims did not lie; their memories, shaped by stress and procedural flaws, led them astray.

Patterns emerge:

- Early show-ups or biased lineups can tilt the entire case.

- Feedback inflates confidence and erodes the ability to self-correct.

- Media narratives and community pressure add suggestive weight.

The human cost is severe: years—sometimes decades—lost, and the real perpetrator free to harm others. Reform is not academic nicety; it is a public safety imperative.

Training and Policy: What Works at Scale

Large-scale improvements are achievable and affordable. Evidence-based policies include:

- Statewide model policies requiring double-blind procedures, fair filler selection, standardized instructions, and documentation of confidence.

- Mandatory training on memory science in police academies and continuing education.

- Courtroom reforms: pattern jury instructions on eyewitness reliability; encouraging or permitting expert testimony; pretrial hearings to assess identification fairness.

- Data tracking: agencies record identification outcomes and evaluate rates of known false identifications when cases are later resolved by independent evidence.

The 2014 National Academy of Sciences report “Identifying the Culprit” distilled decades of research into practical recommendations. Jurisdictions that adopted these practices report fewer contested identifications and stronger cases overall. The cost is time and discipline, not expensive technology.

Common Myths, Debunked

- Myth: Memory works like a video camera. Fact: Memory is reconstructive, prone to suggestion and blending.

- Myth: Confidence equals accuracy. Fact: Initial confidence under fair procedures can predict accuracy; later confidence is easily inflated by feedback and exposure.

- Myth: If multiple witnesses agree, it must be true. Fact: Co-witness contamination can align memories that are jointly mistaken.

- Myth: Cross-race identifications are no different. Fact: They carry higher error rates; fair procedures and education are essential.

- Myth: More interviews mean better memory. Fact: Repetition can reinforce inaccuracies and increase suggestibility.

- Myth: In-court IDs are the “gold standard.” Fact: They are often the most biased, given months of exposure to the defendant.

A Brief, Practical Script for Witnesses After a Crime

Most people will never receive formal training, but you can protect your own memory if the worst happens.

- As soon as safe, write everything you recall. Include sights, sounds, smells, and your internal state. Note uncertainties explicitly.

- Do not discuss details with other witnesses. Say, “I need to preserve my own memory; let’s talk later.”

- Avoid media about the incident. Don’t watch videos or scan photos online until you’ve completed official interviews.

- When interviewed, ask for open-ended questions and state your confidence with numbers (“about 60% sure”). It’s okay to say “I don’t know.”

- Resist pressure to identify someone if unsure. The right answer may be “Not present.”

- After the interview, document whether anyone said anything that could bias your memory (“Good job,” “That matches what we had,” or “The other witness picked the same person”).

- Get rest. Sleep stabilizes memory but also locks in errors; better to consolidate your own fresh, uncontaminated account.

These steps don’t guarantee accuracy, but they meaningfully reduce the risk of later regret.

The Human Story Behind the Science

At the core of eyewitness science is a paradox: the same brain that lets us recognize a loved one across a crowded station can mistake a stranger for a criminal. We’re built to extract meaning quickly with incomplete information—a lifesaving skill in the wild, a liability in a courtroom.

The path forward is not cynicism about witnesses; it’s humility about memory. When the system respects human limits—by adopting rigorous procedures, educating jurors, and valuing objective corroboration—eyewitnesses remain powerful contributors to truth rather than sources of tragedy.

Imagine that convenience store again: fluorescent lights, a flash of metal, the rush of fear. A fair process won’t change what happened, but it can change what we do next. It can preserve the fragile strands of memory without twisting them into something they’re not. In that care—mundane, procedural, unglamorous—lives justice.

Forensic Science Psychology Forensic Psychology Cognitive Psychology Public Safety Criminal Justice Wrongful Convictions Law & Policy memory science misinformation effect weapon focus effect cross-race identification stress and arousal lineup procedures double-blind lineup cognitive interview confidence-accuracy calibration estimator vs system variables DNA exonerations policy reform

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts