Can Public Libraries Survive Without Government Funding

10 min read Exploring whether public libraries can survive without government funding by examining alternative financial models, community support, and real-world experiments. (0 Reviews)

Can Public Libraries Survive Without Government Funding?

Introduction

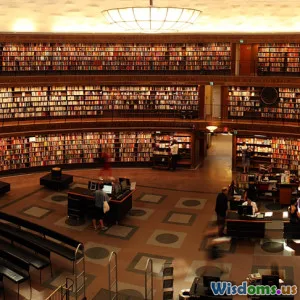

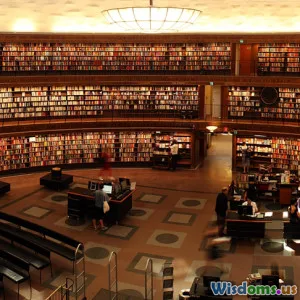

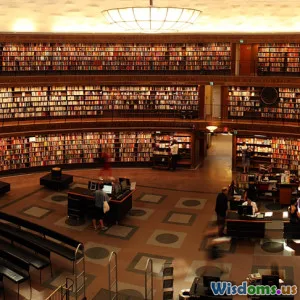

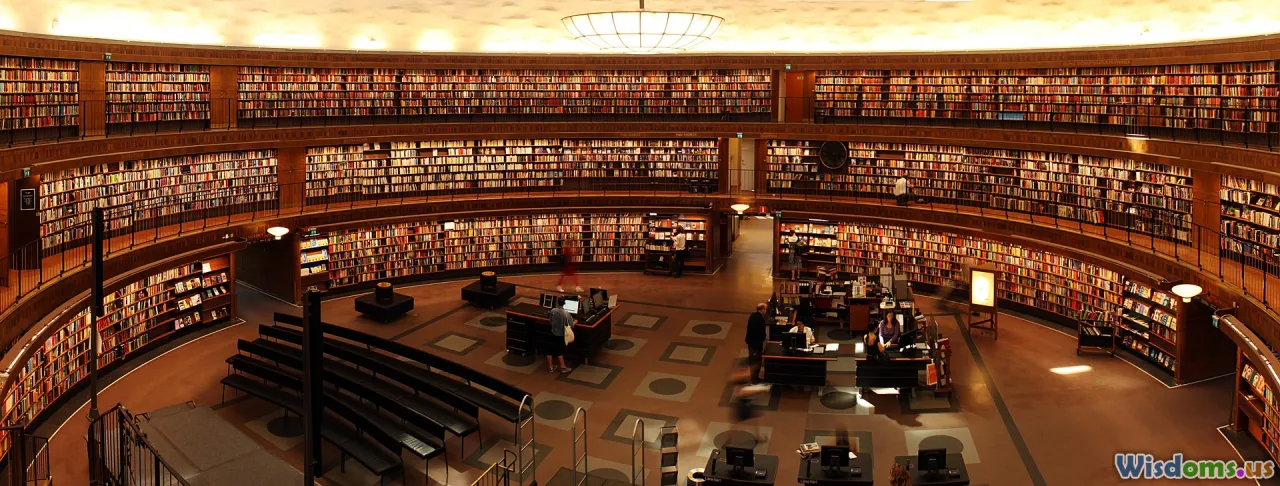

Public libraries stand as pillars of knowledge, community, and equal opportunity. Traditionally, they have flourished under the umbrella of government funding — municipal, state, or federal — ensuring free access to books, digital resources, and various programs for all citizens. But what happens when these crucial funding sources diminish or disappear? Can public libraries truly survive without government backing? This question is not merely hypothetical; it's a pressing issue for libraries worldwide facing austerity measures, shifting governmental priorities, and economic challenges. The survival of these institutions carries immense societal implications. This article dives into the multifaceted debate around public libraries' funding, investigates alternative financial models, and examines how these community focal points adapt — or falter — without government support.

The Traditional Funding Model of Public Libraries

Government as the Primary Supporter

Historically, public libraries have been financially dependent on government funding streams. According to the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Public Library Survey, approximately 90% of U.S. public library funding comes directly from local, state, and federal government budgets. These funds cover infrastructure maintenance, salaries for librarians and staff, acquisition of books and technologies, and programming.

Government funding is generally considered a democratic mechanism to keep libraries free from commercial bias and accessible to all societal segments regardless of economic status. This foundational model emphasizes libraries as a public good, benefiting the entire community.

The Impact of Budget Cuts

Yet, this model's vulnerability was spotlighted during economic downturns, such as the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, Fort Worth Public Library in Texas faced a crippling budget cut of 16% in 2009, resulting in reduced hours, layoffs, and slowed expansion efforts. Such cuts often force libraries to contemplate closures or reduced service, fundamentally challenging the mission of free public access.

Exploring Alternative Funding Models

Given instability in government allocations, many libraries have pursued alternative funding strategies to supplement or even replace governmental support. These models vary in scope and success, often depending on local community engagement and innovative thinking.

1. Philanthropic Donations and Partnerships

Private donations, endowments, and corporate sponsorship have increasingly played roles in library funding. The New York Public Library, for example, raised millions through capital campaigns and private donors to upgrade its infrastructure and expand services.

However, relying on philanthropy carries risks. Donor priorities may shift, causing unpredictable funding streams. Moreover, corporate sponsorship might challenge the library’s impartiality or free access principles, particularly if sponsors seek branding or influence.

2. Revenue from Services and Commercial Ventures

Some libraries have experimented with generating income through xeroxing, printing, café rentals, or event hosting. Scandinavian countries have piloted membership fees for specialized resources or workshops.

Yet, this approach can blur the line between public resource and commercial enterprise, risking the alienation of marginalized groups who rely on free services. For instance, London's idea to charge for digital resources was met with widespread criticism for limiting access to disadvantaged communities.

3. Community Fundraising and Crowdfunding

Grassroots approaches like crowdfunding campaigns have empowered communities to rally around their libraries. When the Joe Stork Memorial Library in Iowa faced closure from budget constraints, a local crowdfunding project raised over $50,000 to keep operations running temporarily.

While crowdfunding can demonstrate community support, it alone rarely creates sustainable income to maintain ongoing operational expenses.

4. Public-Private Partnerships

Some municipalities have pursued partnerships where public libraries lease space or share operations with private entities — such as tech companies or educational institutions — to reduce overhead. The Helsinki Central Library Oodi, although government-funded, has collaborations that enhance resources and visitor experience without direct funding burdens.

These partnerships may provide financial buffers but necessitate careful oversight to maintain autonomy and public mission.

Can Libraries Survive Without Government Funding?

Case Studies and Real-World Examples

A. The UK Model

In parts of the United Kingdom, austerity led to libraries transferring control to non-profit organizations or community trusts. The Wandsworth Borough Council handed management to a charitable trust in 2014.

Survival is feasible in such cases but depends on strong volunteer bases, local philanthropy, and continued community engagement. However, operational challenges often include staff turnover, reduced service hours, and difficulty maintaining collections.

B. US Community Library Initiatives

Community-run libraries have emerged, particularly in rural areas. The Moreau Community Library in New York operates primarily on donations and volunteer staffing.

This approach champions local responsibility but often struggles with scale. Without paid staff or consistent funding, these libraries typically offer limited hours and smaller collections.

Societal Implications of Loss

Libraries do more than lend books; they serve as digital access points, educational hubs, cultural centers, and sources of social equity. Loss or depletion of service directly impacts literacy rates, workforce development, and community cohesion.

Data from Pew Research Center shows that 87% of Americans believe that libraries provide critical resources beyond books, such as internet access — crucial for economically disadvantaged population groups.

The Philosophical Debate: Public Good vs. Market Solutions

At its core, the question touches on the role of public goods and whether market mechanisms can sustain such institutions. Public libraries embody egalitarian values and seek to democratize knowledge. Substituting governmental support with market-dependent models threatens to turn a right into a privilege.

The Path Forward: Mixed-Funding and Sustainable Models

Hybrid Funding Approaches

The future likely resides in hybrid models blending government support with diversified funding. Partial government funding — perhaps diminished from historical levels — paired with strategic philanthropy, community engagement, and selective revenue streams generated a balanced approach.

Increasing Advocacy and Public Awareness

Stronger advocacy can influence government priorities to allocate funds towards libraries. Initiatives like the #SaveOurLibraries movement illustrate how public pressure can revive policy attention.

Embracing Technology and Innovation

Investing in digital platforms expands access beyond physical walls, potentially reducing infrastructure costs. For example, the State Library of Queensland’s digital lending has expanded service reach effectively.

Enhanced Community Involvement

Libraries can deepen ties with local stakeholders, building volunteer and donor networks to supplement financial pressures. Tesla founder Elon Musk’s coupling of philanthropic activities with public causes exemplifies the power of engaging high-profile backers.

Conclusion

Can public libraries survive without government funding? The clear answer is nuanced. While some models demonstrate that libraries may continue operations through alternative resources, government funding remains a cornerstone for their equitable, sustainable operations. Without it, libraries risk losing their universality, scale, and social missions.

Ultimately, public libraries symbolize a collective investment in knowledge, democracy, and community well-being. Preserving these institutions requires not only diversified finances but also sustained public advocacy, innovative leadership, and strategic partnerships. As government budgets fluctuate, the imperative for resilient, hybrid funding models that uphold libraries as free, accessible spaces grows ever stronger.

The question should not be whether public libraries can survive without government funding, but how society can innovate and collaborate to ensure that these treasure troves of knowledge remain vibrant for generations to come.

References:

- Institute of Museum and Library Services, Public Library Survey Data, 2021.

- Pew Research Center, Libraries in the Digital Age, 2018.

- Fort Worth Public Library Budget Reports, 2009.

- London Libraries Campaign, Charging Controversies, 2016.

- Helsinki Central Library Oodi, Annual Reports, 2023.

- UK Government Library Transfer Initiatives, 2014-2020.

- Moreau Community Library Financial Statements, 2022.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts