Trends in Poetry From Sumerian Tablets to Today

38 min read A concise journey through poetry’s evolving forms—from Sumerian cuneiform and oral epics to modern free verse, spoken word, and AI—spotlighting themes, technology, and audience shifts. (0 Reviews)

Poetry began before pens and paper, when memory was a technology and the body a metronome. People sang to keep time with harvests, oared boats, and sorrows. They sculpted speech into lines so it could be carried across distances and generations. Today, poetry fits inside a phone screen, streams in open mics, and remixes centuries of forms in a single chapbook. The thread running through it all is human attention: a hunger to pattern emotion and thought in language that stays.

Across eras, the dominant trend has not been endless novelty but a pendulum swing. Poetry moves from oral to written, from performance to page, from strict pattern to freedom—and then it loops back. Each swing absorbs techniques, metaphors, and cultural needs from the last. To read or write poetry today is to stand at a crossroads where Sumerian tablets, Persian ghazals, Renaissance sonnets, haiku notebooks, and Instagram squares all meet.

Clay, Cane, and Chorus: The Birth of Written and Performed Verse

The earliest surviving poems were impressed into clay with reeds and chanted in communal spaces. In ancient Mesopotamia, poets and priests recorded laments and epics on tablets as early as the third millennium BCE. The epic cycle around Gilgamesh, refined across centuries and preserved on Akkadian tablets, demonstrates a pattern that still echoes: repetition, formulaic epithets, and parallelism built for oral performance and memory. The high priestess Enheduanna, who lived in the 23rd century BCE, composed temple hymns that make her one of the first named authors in recorded history. These hymns braid civic ritual with private feeling, a template for the public-intimate role poetry often plays.

Egyptian love lyrics from the New Kingdom add another early strand: the short lyric poem. Stanzas compare lovers to lotus flowers and geese along the Nile, and many poems likely accompanied music and dance. Meanwhile, Hebrew psalms and Near Eastern laments used parallelism—balancing a thought in lines that repeat with variation—to create rhythm without strict meter. This technique is adaptable and remains common in contemporary free verse.

If clay tablets anchored poems to the page, bodies anchored poems to performance. In archaic Greece, epic singers used dactylic hexameter as a memory scaffold; choruses danced and sang in drama festivals; and lyric poets carried personal songs on the lyre into dinner parties and public games. Poetry was not just words but a multichannel event—voice, instrument, movement, audience response.

Key trend: early poetry optimizes for memory. Devices like refrain, stock phrases, and patterning allowed stories to be portable. Even now, effective spoken word borrows these tools: repeated hooks, chantable lines, and sonic patterns that invite the audience in.

Practical prompt: write eight lines about a journey using a repeating kernel—return to the same noun or verb in every line but alter its context. Notice how repetition builds momentum and memory.

Memory Machines: Meter, Refrain, and the Oral Toolkit

Before widespread literacy, poets needed blueprints that brains could build with. Three devices recur across continents:

- Meter: patterned stresses and syllables. Greek epics used long and short syllables; Sanskrit verse calibrated syllabic length and morae; later English meters counted stresses.

- Parallelism and refrain: repeating structures with variation, common in Psalms, West African praise poetry, and ballads.

- Formula and epithet: reusable phrases and images that function like Lego bricks, letting performers improvise within a structure.

Consider the ballad form that traveled through Europe and into the Americas. Its quatrains and ABCB rhyme scheme, with alternating tetrameter and trimeter, made it easy to remember and dance to. The same pragmatic logic appears in West African griot recitations, where set openings and praise-name patterns provide continuity while accommodating changes in audience and occasion.

In a crowded bar or a village square, performance dictates clarity. Lines need percussive control and a spine strong enough to withstand noise and interruption. Modern slam poets have rediscovered this. The competitive stage rewards crisp openings, scaffolding phrases that can be reprised, and a climactic return to a core image.

How-to tip: When drafting a spoken piece, test it by walking while reciting. If you lose breath or stumble at the same spots, your structure might need more internal signposts: a refrain, a switchback phrase, or a metrical groove.

Lyric Turns in Greece, India, and China

As communities diversified and writing stabilized, poetry narrowed its focus from divine and imperial subjects to personal experience. This lyric turn happened in parallel across cultures.

- Greece: Sappho’s compact stanzas and Pindar’s odes show how lyric negotiates intimacy and public honor. Sappho crafts micro-dramas of desire with finely tuned musicality, while Pindar deploys dense mythic allusion and highly structured strophic patterns to praise athletes.

- India: The Rigveda preserves hymns that predate classical Sanskrit lyric, while later poets like Kalidasa refined sensuous description and emotional nuance. The aesthetic theory of rasa, elaborated between roughly the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE, offered a systematic vocabulary for emotional flavors, which continue to inform Indian poetics.

- China: The Classic of Poetry (Shijing), compiled between roughly the 11th and 7th centuries BCE, collects folk songs, court odes, and didactic pieces. Its frequent use of the metaphor of cutting and weaving offers insight into early agricultural life and social order. Later, in the Tang dynasty, regulated verse would codify tonal patterns, but even the early poems rely on balanced structure, parallel images, and concise diction.

The common trend is compression paired with resonance. Lyric poems become portable containers for private feeling that can still travel through public space.

Actionable reading trio: read a Sappho fragment, a Shijing poem, and an early Sanskrit hymn back-to-back. Make a list of concrete images. Then write a four-line poem that swaps one image from each tradition into a single scene from your life.

Empire and Elegy: Rome, Han, and Classical Refinements

As empires consolidated, poets developed refined techniques to navigate power and personal expression. In Rome, Virgil’s epic crafted a national myth while Horace perfected the Horatian ode’s conversational tone. Catullus and Ovid advanced elegiac couplets that allowed colloquial bite and erotic wit. These couplets, alternating dactylic hexameter and pentameter, model a trend still alive today: counterpoint. Placing one line against another creates tension, irony, and closure.

In China, Han fu fused prose and verse in rhapsodic catalogues that praise and critique imperial grandeur. The fu’s ornate description anticipates later global trends in list poems and documentary verse. While Tang regulated verse lies ahead historically, the impulse to balance lines and images emerges early, encouraging poets to treat the poem as a machine of symmetry and contrast.

Modern takeaway: even in highly formal contexts, poets find space for subtext through technique. Counterpoint, juxtaposition, and formal constraints can smuggle critique into praise.

Exercise: write two-line stanzas where the first line praises a modern technology and the second undercuts it. Let sound and rhythm differ slightly between lines to emphasize the turn.

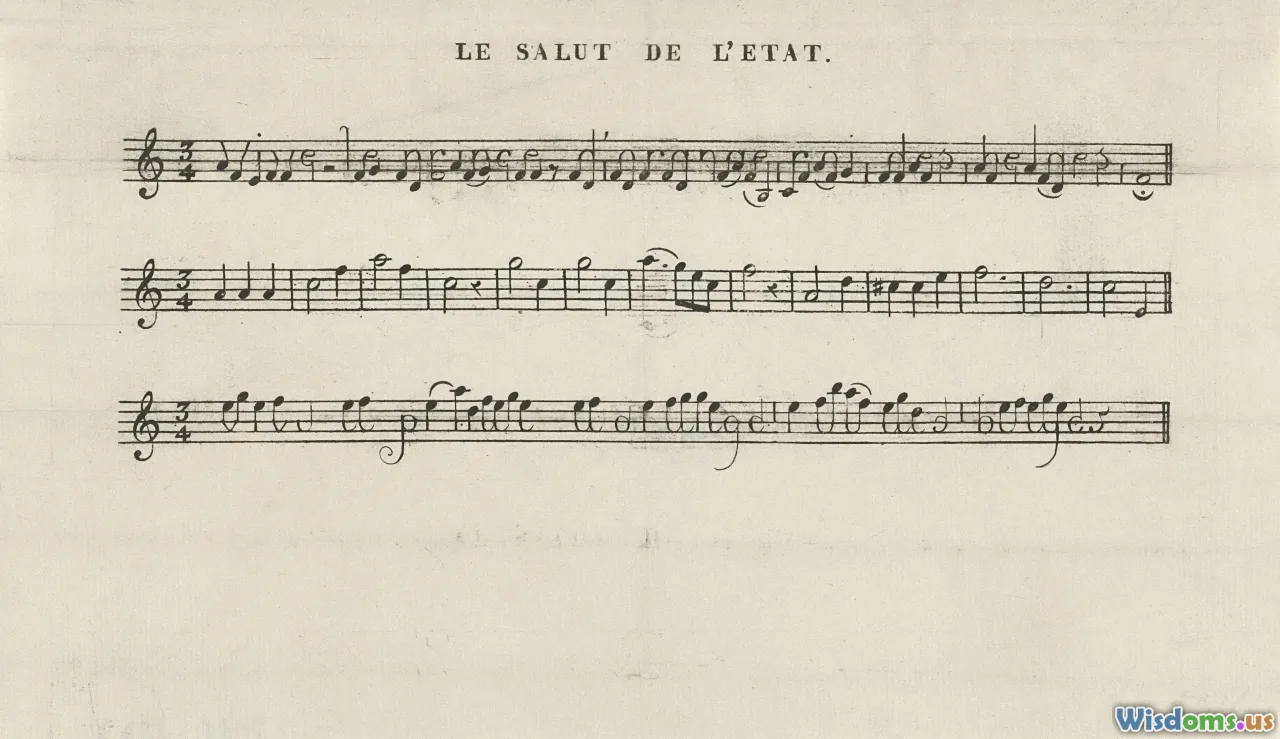

Sacred Forms and Courtly Songs: Medieval Worlds

Between the 7th and 15th centuries, poetry in many regions became a medium of devotion and courtly sociality. Arabic and Persian poets developed the ghazal, a sequence of autonomous couplets unified by rhyme and refrain, often orbiting longing, divine or human. The radif (a repeated phrase) and qafia (rhyme before the radif) create a sonic signature that lets each couplet stand alone and also resonate with the whole. Later, poets like Hafiz and Saadi would carry this form to dizzying heights of wit and spiritual double-vision.

In Europe, troubadours in Occitania crafted songs of fin’amor for noble courts, generating fixed forms and a vocabulary of distance, secrecy, and desire. These songs spread across languages, seeding the canzone, ballade, and later villanelle. In Japan, court poets refined waka into the tanka and experimented with collaborative renga that would eventually lead to haiku centuries later. Across Korea, the sijo compressed philosophical argument into a tripartite lyric. Hebrew piyyut and devotional poetry flourished in liturgical settings, weaving scriptural allusion with contemporary needs.

Trend note: social performance dictates form. When a poem must circulate as song or in salons, repetition and bright rhetorical turns prosper. When a poem must live inside a ritual, balance, clarity, and coded speech do the heavy lifting.

How to borrow: try a modern ghazal. Choose a refrain, perhaps a brief phrase anchored in the present (for example, on the train). Write at least five autonomous couplets. Keep the refrain at the end of each line two and rhyme right before it. Add your name in the final couplet as a signature gesture in homage to tradition.

Renaissance Engineering: Sonnets and Set Pieces

With the rise of printing and the rediscovery of classical rhetoric, European poets engineered compact forms for persuasion and display. The sonnet became a sleek machine whose volta, or turn of thought, introduced a hinge midway through the poem. Petrarch built a template of octave and sestet that dramatizes desire deferred; Shakespearean variants carved room for three distinct quatrains feeding into a couplet snap. Spenser wove interlocking rhymes into a continuous chain.

What made the sonnet dominant for centuries was its modularity. It balances argument and emotion within a predictable length and texture. Translating that pattern into today’s context suggests a practical lesson: design a length and shape for your recurring ideas. If you often write about climate grief, perhaps you need your own 12-line blueprint with a pivot at line nine and a compressed couplet at the end. Constraint can foster courage; it tells you where to aim and where to turn.

Quick how-to: pick a subject and write a 14-line poem where line 9 must contain a reversal phrase such as but, still, or yet. End with two short lines that answer the opening image. Do not worry about rhyme; let the architecture do the work.

Metaphysical Spark and Enlightenment Polish

Seventeenth-century metaphysical poets like John Donne and George Herbert embraced wild similes—conceits that stitch distant domains together. A pair of compasses to describe lovers, a flea as a marital bed—these are strategies to extend thought beyond habit. Soon after, eighteenth-century neoclassicists polished language into crisp heroic couplets. Alexander Pope’s iambic pentameter rhymed pairs shaped public discourse, satire, and moral fable.

The trend here is a tension between imagination’s leap and society’s polish. Both aim at clarity, but through different roads. The metaphysical poem wagers that audacity yields insight; the couplet wagers that order yields authority.

Actionable advice: draft a metaphysical conceit today by choosing two items at least three categories apart—say a cloud database and a reef—and map five properties from one onto the other. Then, for discipline, rewrite your best lines into rhymed couplets to test whether the idea survives polish.

Romantic Revolutions: Nature, Self, and Nation

Around 1800, poets across Europe and the Americas pivoted to the inner life and the sublime in nature. The Romantic era insisted that ordinary language could carry extraordinary experience. Poets celebrated emotion, rebellion against rigid social orders, and the individual voice, while national literatures looked for myths and landscapes to anchor themselves. In the United States, Walt Whitman’s long free-verse lines stretched the page to match a continental horizon, while Emily Dickinson’s short, slant-rhymed lyrics turned the mind into an asteroid field of flashes and dashes.

If earlier trends favored formal courtship with readers, Romanticism pressurized sincerity and spontaneity. The ballad was recovered as a democratic form; the ode was recast as interior meditation. Around the world, parallel movements sought a language adequate to political change and personal truth.

Practical prompt: go for a long walk and write couplets where each second line returns to an observation in the landscape. Err on the side of sensory detail. Then remove half the adjectives and see if the feeling intensifies through image rather than assertion.

Modernism Breaks the Line

The early 20th century fractured traditions under the pressure of technological change and global conflict. Modernist poets proposed that poetry must be new in technique to be faithful in spirit. Imagism enacted a manifesto of direct treatment, precise word choice, and musical line. Ezra Pound’s two-line apparition in a metro station showed how compression and juxtaposition could replace narrative. T. S. Eliot’s collage of voices in The Waste Land foregrounded fragmentation as form, while H. D. and others honed luminous images.

Elsewhere, Futurists celebrated speed, Dadaists embraced nonsense as critique, and Surrealists mined dream logic. Across languages, poets experimented with typography, free verse, and multilingual code-switching. Haiku’s brevity and emphasis on the present moment influenced Western minimalism. In Latin America, Vicente Huidobro and later the concrete poets made the page a visual field.

What emerged was not just freedom from meter but a new responsibility: to invent a local order in each poem. Free verse is not lack of form, but a bespoke rhythm that fits subject and voice. The skill is in hearing lineation as breath and unit of meaning.

Technique drill: print a draft and mark your natural breath pauses. Break the lines there and read aloud. Adjust enjambment to place pressure on unexpected words. Aim for one image per line to test clarity. Later, compare this shape to a version in strict meter to see which serves your content.

Voices of Identity: Harlem Renaissance to Postcolonial Currents

In the 1920s, the Harlem Renaissance braided jazz rhythms with African American speech and experience. Langston Hughes dramatized the music of everyday talk and the blues’ structure of call-and-response. Claude McKay balanced sonnets with radical politics, demonstrating how inherited forms can carry new social charge. Later, Gwendolyn Brooks would explode the sonnet from within, and the Black Arts Movement campaigned for poems that were by, for, and about Black communities.

Postcolonial poetry worldwide used English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese as both toolkit and site of resistance. Derek Walcott’s epics carried Caribbean seascapes into Homeric conversation. Mahmoud Darwish braided land and exile into lyrical testimony. In South Asia, poets such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz and, later, Agha Shahid Ali expanded ghazal traditions into modern languages, with Ali championing the English ghazal’s formal integrity.

Trend insight: identity is not theme but method. Diction, rhythm, and narrative stance become political choices. Formal code-switching—sliding between sonnet and blues stanza, between qawwali echo and free verse—creates a map of belonging and estrangement.

Craft tip: inventory your linguistic registers—home talk, academic language, slang, prayer. Write a poem that moves through at least three registers across stanzas. Track how the emotional weather changes when the diction shifts.

Confessional Candor and the Workshop Era

Mid-century American poetry turned inward with confessional work that made private pain a public art. Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, and Anne Sexton treated family histories, mental health, and taboo subjects with an intimacy that felt unprecedented in print. Their syntax often walked a tightrope between lyric beauty and raw disclosure, demonstrating how craft intensifies honesty rather than masking it.

At the same time, the academic study of creative writing expanded. The Iowa Writers’ Workshop, founded in the 1930s, influenced a model replicated across universities. Workshops fostered close reading, line-by-line critique, and exposure to a wide range of traditions. The era standardized certain craft terms—image, line break, persona—and broadened the audience of people trained to read and write poems.

The risk of institutionalization is sameness, but the benefit is shared technique. Contemporary poets increasingly use confessional tactics as one mode among many, combining memoir with research, documentary evidence, and formal experiment.

How-to idea: write a personal poem that includes three external documents: a weather report, a medical instruction, and a bit of public signage. Let each document interrupt your voice. Watch how the collisions produce unexpected meaning.

Performance Returns: Slam, Spoken Word, and Global Festivals

In the 1980s, slam poetry reintroduced competition and the live audience as decisive forces. At the Green Mill in Chicago, a weekly format founded by Marc Kelly Smith turned poems into scored performances. National events proliferated in the 1990s and 2000s. Television and online platforms amplified the reach of voices that did not always fit neatly into print journals.

Spoken word sharpened a different skill set: timing, gesture, and the arc of a three-minute narrative. The best performers calibrate tone shifts, strategic silence, and recurring motifs to land impact in noisy rooms. The craft overlaps with theater and comedy; poems often answer a prompt or debate a social issue in real time.

Trend takeaway: performance is not the enemy of complexity. Many page-first poets now test draft paragraphs at open mics to hear where the audience leans in. Conversely, stage-first poets increasingly publish books that translate rhythm into typography.

Actionable practice: record yourself performing a poem. Note where your voice naturally swells or drops. In revision, adjust line breaks and punctuation to cue those dynamics for a silent reader.

Digital Poetry: Screens, Streams, and Scrolling

The smartphone changed distribution and form. Micro-poetry thrives in platforms where a few lines must compete with photos and headlines. Instagram poets present clean, serif stanzas on textured backgrounds; Twitter encouraged one-breath poems, aphorisms, and threads; TikTok and YouTube reanimated the recitation tradition with visual storytelling. E-books and apps enabled hypertext and interactive poems that branch or respond to touch.

This ecosystem rewards clarity, brevity, and shareable hooks. But it also opens new experimental routes: blackout poems made from newspaper erasures; augmented reality overlays that make a poem visible only in certain locations; algorithmically generated texts that explore pattern and chance. The day’s feed accelerates cycles of trend and backlash, pushing some poets to refine a signature voice and others to explore serial formats.

Data point: in the late 2010s, industry research in the United States documented double-digit growth in poetry sales, with spikes around cultural moments such as a high-profile inauguration reading. National Poetry Month, begun in 1996, drives annual surges in reading and programming, and public libraries report robust attendance at poetry events tied to seasonal themes.

How to thrive online without flattening your voice:

- Treat platforms as distinct stages. A serial poem may work on Instagram; a research-rich documentary poem might live better on a personal site.

- Use alt text to describe images in text-based poems; it is both inclusive and poetic practice.

- Draft three versions of the same poem: long form for print, mid-length for web, and a distilled four-line version for social sharing. Notice what remains essential.

Translation, Hybridity, and the World Poem

Translators have always shaped what poems live in other languages. In the last century, that role expanded as presses and online journals built global networks. Many English-language poets write through translations and hybrid identities. A poem can be a port where Arabic ghazal structure, Japanese seasonal attention, and Caribbean speech meet to trade.

Translation is not mere ferrying of words but re-creation of effects. A translator must choose whether to preserve rhyme at the expense of nuance, or maintain image clarity by letting go of sonic pattern. These choices remake trends: when a translated haiku uses plain diction and omits punctuation, new poets learn that spareness can hum loudly. When an English ghazal keeps the radif but loosens meter, poets learn the power of recurrence even without quantitative measure.

Practical exercise: pick a poem you cannot read in the original language. Gather three different translations. Make a matrix of what is consistent: images, pronouns, verb tense. Write your own version that prioritizes one effect—sound, image, or argument. Label it after but not from the original, and explain your choices in an endnote. This practice builds empathy for historical forms and reminds you that every poem is a set of decisions.

Form Swap: Ghazal vs Sonnet and Other Productive Crossovers

To understand trends in poetry is to see how forms migrate and mutate.

- Ghazal vs Sonnet: the ghazal’s autonomy of couplets contrasts with the sonnet’s continuous argument. The ghazal offers multiple entry points and a refrain that becomes mantra; the sonnet drives toward a hinge and a snap. Hybrid idea: write a sonnet in couplets where every second couplet ends with a repeated phrase. The result layers Western argument with Eastern recurrence.

- Pantoum and Villanelle: the pantoum, from Malay oral tradition, and the French villanelle both rely on line repetition. Each creates a spiral motion. Many contemporary poets use them to explore memory, trauma, and obsession because the form mimics involuntary return. Tip: choose your repeating lines from the middle of a thought rather than its edge to invite evolution rather than mere echo.

- Haibun: combining prose and haiku, the haibun offers a diary mode with a crystallized coda. In digital settings, this hybrid thrives as carousel posts or scroll essays with embedded micro-lyrics.

Actionable crossover: draft a 12-line poem where lines 1, 5, and 9 are identical except for one changing noun. Insert a two-sentence prose paragraph after line 6. Notice how the prose resets the field and the final repetition reframes your theme.

Reading Laterally: A Practical Syllabus

A single national tradition cannot tell the story of poetry’s trends. Reading laterally across time and geography helps you detect recurring solutions to recurring human problems. Here is a compact plan you can complete in a month:

Week 1: Origins and Orality

- One Sumerian hymn attributed to Enheduanna in a reputable translation; notice invocation strategies.

- A set of Egyptian love poems; note comparisons drawn from daily life.

- A Psalm with parallelism; mark the structure of repetition with variation.

Week 2: Lyric Refinements

- A Sappho fragment alongside a Pindar ode excerpt; map intimacy vs public voice.

- Several poems from the Classic of Poetry; observe natural images as social code.

- A Sanskrit lyric from Kalidasa; identify rasa cues.

Week 3: Forms in Flower

- A classical Latin elegy; analyze the two-line logic.

- A ghazal from a Persian master; annotate the refrain and signature.

- A tanka and a linked-verse excerpt; watch collaboration and pivot words.

Week 4: Modern and Contemporary Blends

- One long free-verse piece from Whitman and a minimal lyric from Dickinson; compare scale.

- An imagist poem and a collage-like modernist classic; chart compression vs fragmentation.

- A contemporary spoken word piece on video and a page poem by a living poet who uses hybrid forms; note how each crafts climax and closure.

Each week, write a short reflection naming one device you can carry forward. Then produce a poem that adopts the device in an unrelated subject.

Metrics of the Moment: What Data Says About Poetry Today

It is easy to narrate poetry’s history as a series of revolutions; it is harder to gauge its present. Some indicators help. Book industry reports in the late 2010s noted robust growth in poetry sales in the United States, particularly among younger readers and online-driven titles. Major civic occasions, such as inauguration readings, routinely drive sales spikes and view counts for poetry titles and videos. April’s National Poetry Month prompts thousands of public events, from subway placards to school workshops, pulling poetry into daily circulation.

Digital metrics show communities forming around hashtags and online magazines, while podcast downloads and YouTube channels demonstrate appetite for criticism and craft talk. Meanwhile, MFA programs graduate hundreds of poets yearly, and small presses continue to innovate with chapbook formats, bilingual editions, and community-based publishing models. International prizes bring poetry from different languages into the Anglophone spotlight, and translation imprints expand readership beyond borders.

What this means for you: the audience is fragmented but plentiful. Specificity wins. A chapbook about urban beekeeping might not reach a mass market, but it may find a devoted niche online and at local readings. Collaborative events that pair poetry with music, visual art, or science outreach tend to generate broader attendance because they cross community networks.

Practical strategy:

- Track your own data ethically: note which poems resonate at readings and online. Use that feedback to shape sequences without letting it flatten your range.

- Partner with organizations outside literary circles—a historical society, a climate group, a hospital arts program—to place your work where it can matter directly.

What Stays the Same (and How to Use It)

From Sumerian laments to a poem posted five minutes ago, three constants shape poetic trends.

- Attention to pattern: whether in meter, refrain, or image systems, poems make order. Even free verse relies on pattern recognition. Develop an ear for the structures you love and name them. Then vary one element at a time in new drafts.

- Social context: poets write for and with communities. Festivals, salons, workshops, feeds, and funerals all demand different balances of clarity and complexity. Before writing, ask where a poem will live first. Compose to that acoustic space, then adapt it elsewhere.

- Emotional necessity: the best poems answer why now. Sometimes the answer is public—a march, a law, a war. Sometimes it is personal—a diagnosis, a parent’s voice fading, the first steps of a child. Let necessity choose form: a villanelle can hold obsession; a documentary collage can hold institutional critique; a haiku can hold awe.

An actionable final practice: keep a forms journal. Each week, pick a form across this historical arc—a Sumerian-style parallelism, a ghazal, a sonnet, a pantoum, a prose poem, a haibun, an erasure. Draft a poem in that form on a current subject in your life. At month’s end, select the two drafts that feel most alive and revise them in a contrasting form. This back-and-forth trains you to treat form not as a costume but as an instrument.

Poetry’s trends are not a parade of fashions but a choreography of needs and tools. When you reach back to the tablets and forward to the timeline, you inherit a kit filled with rhythms, shapes, and strategies. Use them to make the next thing that, like a chant in a courtyard or a post on a screen, finds someone who needs it and stays.

Books & Literature Poetry Literary History History of Literature Modernism Epic of Gilgamesh Cuneiform Tablets Culture & Arts Sumerian literature oral tradition classical poetry sonnet form haiku free verse spoken word Beat Generation confessional poetry Instapoetry AI poetry digital humanities

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts