Comparing Sculptural Techniques of Hellenistic Greece and Ancient India

10 min read An insightful exploration of sculptural methods in Hellenistic Greece and Ancient India, revealing cultural influences and artistic techniques. (0 Reviews)

Comparing Sculptural Techniques of Hellenistic Greece and Ancient India

Sculpture serves as a timeless window into the civilizations of our past. Hellenistic Greece and Ancient India, separated geographically and culturally but flourishing during roughly overlapping eras (approximately late 4th century BCE to 1st century CE), produced some of the most influential and expressive sculptural artworks in human history. This article embarks on an in-depth comparison of their sculptural techniques, analyzing the artistic objectives, methods, materials, and symbolic content that defined their legacy.

Introduction

Imagine walking through two distinct ancient cities: one lined with intricately carved Greek marble statues expressing intense emotion and dramatic movement, the other filled with delicately crafted Indian stone and bronze figures emanating spiritual serenity and metaphysical narratives. Each piece reflects the society’s worldview, values, and technical prowess. Through comparing the sculptural techniques of Hellenistic Greece and Ancient India, readers gain a richer understanding of how art evolves beyond borders — forging new paths through cultural exchange and individual creative vision.

Historical and Cultural Contexts

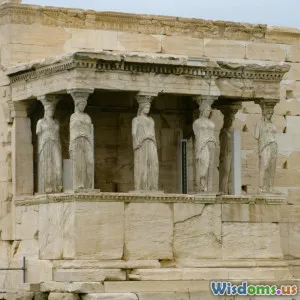

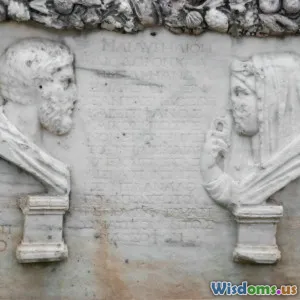

The Hellenistic World

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great (336–323 BCE), Greek culture spread across the Eastern Mediterranean and deep into Asia. This Hellenistic era (circa 323–31 BCE) was marked by dramatic artistic shifts from the idealized classical forms to more expressive, naturalistic, and even theatrical sculpture. The era prized dynamic movement, emotional intensity, and intricate realism. Sculptors like Lysippos, Scopas, and Praxiteles experimented with pose, anatomy, and texture to breathe life into marble and bronze.

Ancient India's Artistic Flourishing

Concurrently, Ancient India experienced major developments especially during the Maurya (circa 322–185 BCE) and subsequent Shunga and Kushan periods. Sculpture here was deeply tied to religious traditions, notably Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. Indian sculptors conveyed spiritual narratives and philosophical ideas through symbolic iconography, deliberate postures (mudras), and intricate detailing often in stone and bronze. The Gandhara and Mathura schools exemplify these approaches, blending indigenous styles with Hellenistic influences introduced through trade and conquest.

Materials and Techniques

Material Choices: Marble, Bronze, and Stone

-

Hellenistic Greece: The primary material was marble, prized for its fine grain and ability to hold detail, alongside widespread use of bronze. Greek sculptors excelled in both mediums, casting large bronze statues with sophisticated techniques like the lost-wax (cire perdue) method, enabling fluid forms and dynamic poses. Marble statues often underwent meticulous chiseling and polishing to achieve intricate musculature and naturalistic skin textures.

-

Ancient India: Indian sculptural traditions primarily utilized sandstone, schist, granite, and bronze. The Gandhara region favored gray schist enabling detailed carving, while Mathura stone was used for more robust and rounded forms. The lost-wax bronze technique was also prevalent—most famously in South Indian Chola bronzes, albeit developed somewhat after the Hellenistic period but rooted in similar casting traditions.

Real-World Insight

The technical mastery of the lost-wax technique remains remarkable in both regions. For example, the famous Bronze Statue of the Dancing Shiva (Nataraja) from later Indian periods reflects a technical lineage that arguably traces back centuries and parallels Greek bronze casting innovations.

Stylistic Characteristics and Artistic Objectives

Artistic Goals in Hellenistic Greece

Hellenistic sculptors pursued:

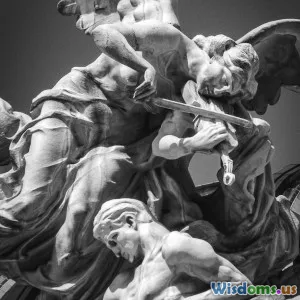

- Realism & Dynamism – Figures display exaggerated motion (e.g., the Laocoön Group sculptures illustrate agony and struggle vividly).

- Emotional Expression – Faces convey psychological states: pain, joy, despair.

- Complexity & Experimentation – Use of diagonal poses, hair and drapery movement, and variation in scale.

Artistic Goals in Ancient India

Indian sculptors focused on:

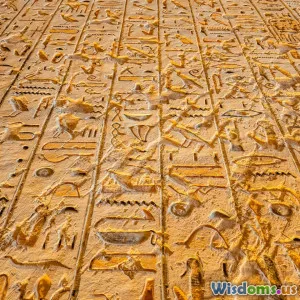

- Spiritual Symbolism – Sculptures often represent deities; iconographic rules guide portrayal.

- Stylized Iconography – Standardized features (but fluid in posture and gesture) communicate narratives and virtues (e.g., the Buddha’s serene countenance and hand mudras symbolizing teaching and fearlessness).

- Narrative Reliefs – Carved panels often illustrate religious stories, aiding devotion and education.

Comparative Example: The Laocoön Group and the Buddha Statues

- The Laocoön Group (circa 1st century BCE) epitomizes Greek dramatic realism—contrasting tension-filled muscles and distorted bodily forms.

- Indian Buddha sculptures, such as those from Gandhara, exhibit calmer facial moods but borrow classical Hellenistic drapery techniques demonstrating cross-cultural influence.

Cross-Cultural Exchanges and Influences

The most fascinating aspect is the evidence of synthesis:

-

Gandhara School: This art form vividly merges Greek artistic realism with Indian spiritual themes. For instance, the naturalistic rendering of drapery and musculature exhibits clear Hellenistic technique merged with Buddhist iconography.

-

Iconographic Transmissions: Indian sculptures reveal emerging features analogous to Hellenistic styles, including contrapposto stances and naturalistic body forms, indicating artistic exchange during and post-Alexander’s campaigns.

-

Later Impact on Indian Sculpture: Such interplay influenced subsequent regional arts, especially in dynamically sculpting figures and managing spatial depth in relief carving.

Technical Execution and Workshop Practices

Hellenistic Workshops

Greek workshops enjoyed specialized craftsmen - carvers, bronzesmiths, and polychromatic painters collaborated carefully. Sculptors such as Praxiteles became renowned with apprentices spreading influence wide throughout the Mediterranean.

Indian Workshops

Indian sculptors often worked within temple complexes or guilds, carefully embedding theology into artistic conventions. Detailed preliminary sketches and molds sometimes guided the final output.

Notably, the repeated use of iconometric grids in Indian art dictated proportions with spiritual significance beyond mere aesthetics.

Legacy and Impact

Hellenistic Greece’s Influence

Hellenistic sculpture shaped Roman art and western artistic ideals for centuries — naturalism, emotional expression, and dynamism remain foundational in modern sculpture.

Ancient India’s Enduring Arts

The forms perfected in ancient India laid the groundwork for classic South Asian temple sculpture and continue to inspire contemporary religious art. The philosophical depth imbued in these sculptures makes them a perennial focus of study for interpreting Indian religio-cultural history.

Conclusion

Comparing the sculptural techniques of Hellenistic Greece and Ancient India reveals a rich dialogue of form, function, and faith. While Greek sculptors emphasized expressive realism and physical dynamism to depict human experience and mythic drama, Indian sculptors focused intently on spiritual symbolism and ritual narratives, achieving serene transcendence through emblematic postures and detailed iconography. Both traditions exhibit remarkable technical mastery—from marble carving and bronze casting to intricate iconometry—that speaks to human creativity's magnificence.

Studying these divergent yet occasionally intersecting techniques yields profound insights not only about ancient societies but also about the universal artistic impulse to communicate deeper truths through sculpture. For art historians, sculptors, and enthusiasts alike, this comparative lens invites continued exploration into how culture, technique, and symbolism intertwine to shape our visual heritage.

References

- Boardman, J. (1995). Greek Sculpture: The Classical Period. Thames & Hudson.

- Huntington, S., & Huntington, J. C. (1985). The Art of Ancient India. Weatherhill.

- Richard Stoneman (2014). The Greek Experience of India. Princeton University Press.

- Susan Huntington (2000). The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. Weatherhill.

- Maria Roxane Osorio Rodrigues (2017). “Cross-Cultural Influences Between Greco-Roman and Indian Art: Analysis of Gandharan Art,” Journal of Art History and Archaeology.

This extensive comparison celebrates the enduring legacy of two of humanity’s greatest sculptural traditions, inspiring deeper appreciation and continuous discovery across the ages.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts