Uncovering the Hidden Purposes Behind Decorative Motifs in Roman Villas

10 min read Explore the hidden symbolism and purposes of decorative motifs in Roman villas, revealing their cultural, social, and psychological roles. (0 Reviews)

Uncovering the Hidden Purposes Behind Decorative Motifs in Roman Villas

The Roman villa, treasured through history for its lavish architecture and intricate art, reveals much more than mere aesthetic preferences. Beneath the layers of frescoes, mosaics, and wall paintings lie symbols and messages that offer insights into the ancient Roman worldview. Decorative motifs in these residences were carefully curated to communicate status, religious beliefs, cultural ideologies, and even psychological comforts. By delving into the hidden purposes behind these designs, we uncover a rich narrative about Roman society and its values.

Introduction

At first glance, the vibrant mosaics and frescoes in Roman villas appear to be just ornamental delights—beautiful patterns and mythological scenes created to entertain guests and please inhabitants. However, exploring deeper reveals that many motifs had specific symbolic and functional purposes. This article unpacks these hidden layers, examining the connection between decorative choices and the broader cultural, political, and social contexts of ancient Rome.

Ancient Roman villas were more than homes — they were statements. The decorating motifs were purposeful tools of communication, expressing wealth, Roman identity, religious convictions, and personal narratives. Understanding the intricacies behind these designs enhances our appreciation of Roman art and offers us a lens through which to view their civilization more vividly.

The Social and Political Language of Motifs

Displaying Status and Wealth

One of the most apparent functions of decorative motifs was signaling social status. The opulence of mosaics and the complexity of painted scenes reflected the owner's prominence and wealth. For example, in the mid-1st century BCE villa at Pompeii, the House of the Faun boasts one of the largest and most elaborate mosaic floors discovered, including the iconic "Alexander Mosaic". This masterpiece not only signaled artistic sophistication but the patron's connection to heroic and imperial narratives, enhancing their social stature.

Mosaic materials also conveyed prestige. Semi-precious stones, colored glass, and imported marble demonstrated not only wealth but a cosmopolitan taste aligned with Rome's imperial reach. Thus, decorative motifs functioned as non-verbal status markers, impressing visitors and reinforcing societal hierarchies.

Political Allegiance and Identity

Roman villas often embedded political allegiance subtleties within their decorative schemes. For example, during the late Republic and early Empire, villas might depict scenes celebrating the Julio-Claudian dynasty or specific emperors as a demonstration of loyalty and political alignment.

In addition, mythological scenes could be tailored to reflect imperial virtues or the owner's association with certain political ideals. The villa of the Emperor Tiberius on Capri used frescoes and mosaics to reflect both divine favor and imperial legitimacy, reinforcing power through iconographic language.

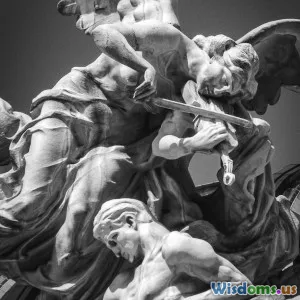

Religious and Mythological Symbolism

Gods and Protective Spirits

Many decorative motifs showcased gods and divine figures intended to protect the villa and its inhabitants. For instance, imagery of Fortuna (goddess of luck) was common near entrances, believed to bring prosperity and ward off evil. In contrast, the presence of Bacchus-related motifs indicated not only celebrations of wine and pleasure but also religious rites linked to spiritual renewal.

In the Villa of Mysteries near Pompeii, intricate frescoes appear to depict initiation into the cult of Dionysus (Bacchus), suggesting that walls served a ritualistic purpose beyond decoration.

Nature and Fertility Symbols

Nature motifs, such as vine leaves, animals, and freshwater sources, often featured prominently to evoke fertility and harmony. These motifs were integral to the Romans’ deep connection with agrarian life and the cycles of nature, promoting well-being and abundance for homeowners who typically managed agricultural estates.

For example, the imagery of cornucopias intertwined with seasonal fruits reflected a desire for unending prosperity. Mosaics depicting gardens or animals subtly referenced Roman ideals of harmony and the domestication of both nature and society.

Psychological and Emotional Purposes

Creating Illusions of Space and Comfort

Roman decorative arts frequently employed trompe-l'œil (trick of the eye) techniques to simulate windows, gardens, or architectural elements, expanding the perceived size and openness of rooms. This was not just artistic ingenuity, but a means to infuse villas with psychological comfort—a respite from crowded urban life.

The use of perspectival frescoes, such as those found in the House of the Vettii at Pompeii, created immersive environments, transforming interior spaces into scenes of pastoral tranquility or grand vistas that invited relaxation and mental escape.

Reinforcement of Cultural Identity and Memory

The villa as a décor-filled space helped homeowners affirm their Roman heritage and intellectual identity. Classical myths were favorites because they reinforced shared values and cultural continuity, reminding inhabitants and guests of their place within the expansive Roman narrative.

As historian Mary Beard notes, "Roman domestic decoration was as much about projecting a cultivated identity as about showing artistic taste." This cultivated identity tied individuals to grand stories of empire, virtue, and destiny.

Practical and Functional Roles of Decoration

Marker of Functions within the Villa

Specific decorative schemes could demarcate different functional spaces. Dining rooms (triclinia) often featured motifs connected with abundance, Bacchus, or scenes of feasting, enhancing the convivial atmosphere. Meanwhile, bedrooms (cubicula) frequently displayed calming pastoral or mythological scenes conducive to rest.

This deliberate design improved the daily lived experience, aligning environment and activity symbolically and functionally.

Protection and Preservation

Certain motifs functioned as apotropaic symbols — meant to protect the inhabitants from misfortune. Imagery such as the Gorgon's head or phallic symbols served as spiritual safeguards, warding off evil influences.

Additionally, quality craftsmanship and durable materials reflected the owner's intent for the villa to endure time, projecting permanence both physically and culturally.

Case Studies: Unveiling Motifs from Famous Villas

Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii

Beyond its famed Dionysian initiation frescoes, the villa’s motifs reinforce religious mystery and a shared communal identity for initiates. The vivid red backgrounds and seated figures engage viewers in a narrative both esoteric and social.

Villa della Farnesina, Rome

This villa is renowned for its mythological frescoes, particularly those by Raphael. The decoration intertwines themes of love, beauty, and mythology, reflecting the refined tastes of the Renaissance patron but built upon classical traditions that highlighted personal identity, intellectual prowess, and cultural continuity.

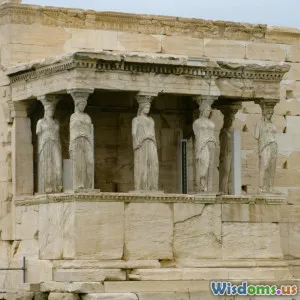

Hadrian's Villa (Villa Adriana), Tivoli

Hadrian’s villa is a monumental example where decorative motifs merged with architecture to evoke diverse cultural references—from Egyptian obelisks to Greek sculptures—demonstrating the emperor’s personal ideology of cosmopolitanism and power.

Conclusion

The decorative motifs adorning Roman villas were far from random embellishments; they were key components of a carefully constructed visual language that fused art, politics, religion, and psychology. Each fresco, mosaic, and ornamental design communicated messages about power, piety, identity, and comfort.

By uncovering these hidden purposes, we gain a richer understanding of Roman life that challenges our view of these artworks as mere aesthetics. Instead, they emerge as vibrant, complex scripts that bring alive the ancient Roman experience—its values, fears, ambitions, and ideals.

This knowledge invites us to look not only at the grandeur of Roman architecture but also at the stories inscribed within walls, reminding us how deeply art can intertwine with human life and culture.

References

- Beard, Mary. The Roman Triumph. The Belknap Press, 2007.

- Clarke, John R. Roman Art. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. University of Michigan Press, 1988.

- Ling, Roger. Roman Painting. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Wall mosaics and frescoes catalogues from archaeological reports of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts