Comparing Zeus and Jupiter Influence on Later Religions

13 min read Explore how Zeus and Jupiter shaped later religious beliefs across Europe and the Mediterranean through mythology, iconography, and cultural syncretism. (0 Reviews)

Comparing Zeus and Jupiter: Tracing Their Influence on Later Religions

Since antiquity, the mythology of the Greco-Roman world has woven itself through time, deeply influencing culture, language, and religious thought across continents. Among the pantheon, Zeus of the Greeks and Jupiter of the Romans stand preeminent—not only as rulers of gods but as archetypes shaping subsequent spiritual traditions. Today, exploring the legacy of these mightiest Olympians reveals nuanced intersections with Christian, Renaissance, and even modern religious ideas.

Divine Sovereigns: Zeus and Jupiter Side-by-Side

Zeus and Jupiter occupy analogous roles in their respective mythologies, both regarded as the king of the gods and lord of the skies. Yet, tracing the origin and development of each deity highlights distinct theological approaches that impacted religious evolution.

The Hellenic Zeus

Zeus, celebrated by Homer and Hesiod, was not merely a sky god; he was the personification of justice, hospitality (xenia), and the upholder of order (cosmos) against chaos. His familiar mythological tools—the thunderbolt and the aegis—depicted his power over the elements and fate itself. Zeus’s role was further ritualized in the Olympic games and in pan-Hellenic oracles such as Dodona and Olympia, imbuing the deity not just with religious but civic-hegemonic power.

The Latin Jupiter

When Greeks and Romans interacted, Zeus became syncretized with Jupiter Optimus Maximus. While retaining similar symbols (the eagle, thunderbolt), Jupiter’s influence extended into Roman jurisprudence and the politics of empire. The Capitoline Triad, of which Jupiter was the chief, symbolized the state’s moral foundation. Jupiter, in Roman prayers and oaths, was not just a god to be revered but an overseer of contracts and a witness to statecraft.

The theological overlap and contrasts between the two set crucial precedents: later religions looked to both as templates for monotheistic and sovereign divine leadership.

Shaping Monotheism: From Polytheistic Kingship to the One God

Much has been written about the move from polytheism to monotheism, especially regarding Christianity’s ascension within the Roman Empire. Zeus and Jupiter, as omnipotent sky fathers, provided a familiar paradigm out of which the Abrahamic conception of the singular all-powerful God could emerge.

The Influence Pathway

The attributes ascribed to Zeus and Jupiter—universal sovereignty, judiciousness, and control over nature—closely mirror those later attached to God the Father. For example, early Christian theologians like Justin Martyr and Clement of Alexandria debated Greek philosophical terms for God and redefined them within a new religious context. They framed God as the Pantokrator—a term echoing the omnipotent aspects of Zeus-Jupiter.

Visual and Linguistic Traces

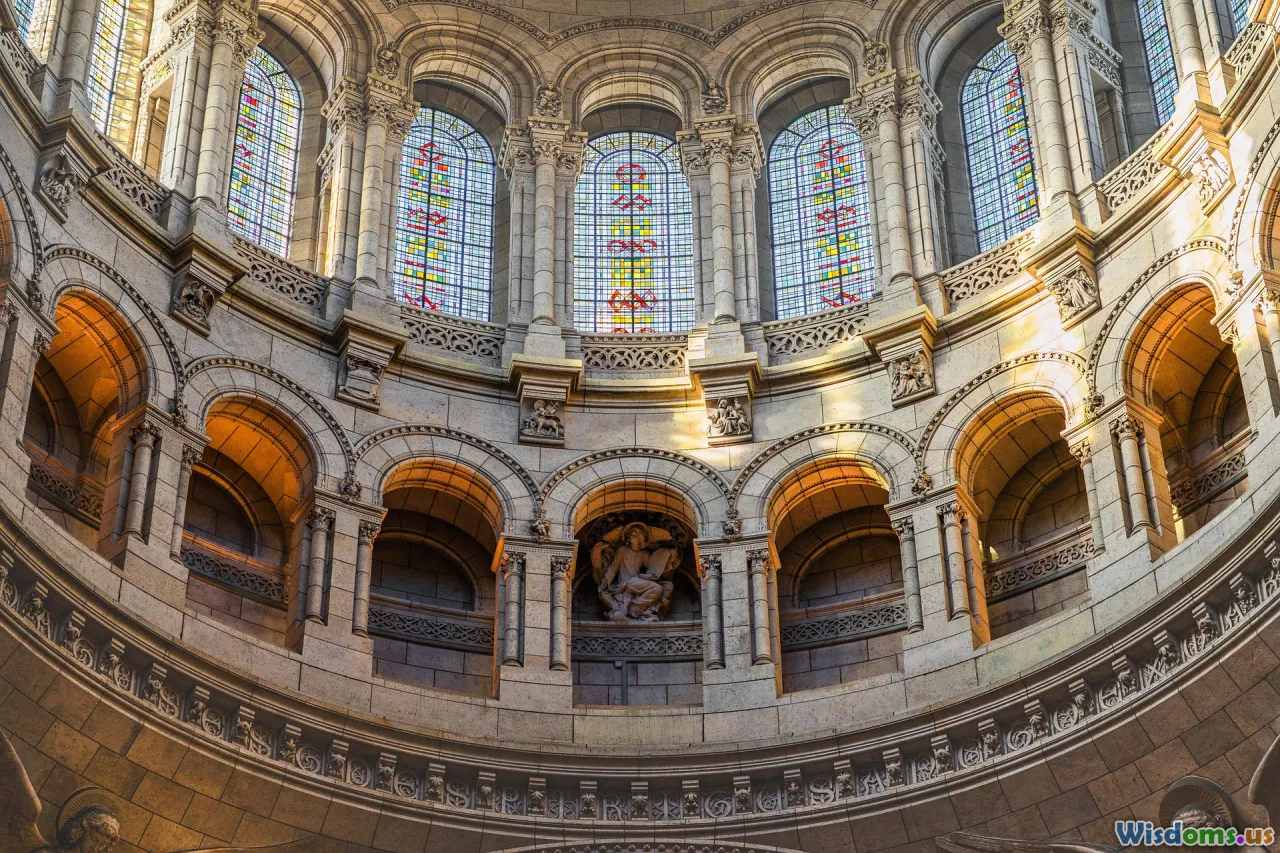

Iconographically, God the Father in Christian art would be depicted as a bearded, authoritative figure, holding or stretching forth a hand much like classical statues of Zeus or Jupiter. This is clearly seen in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel frescoes, where divine authority and benevolence unite, a nod to the ancient gods’ visual language.

Linguistically, the word “Deus”—the standard Latin for God—emerged directly from the same Indo-European root ( deiwos ) as Zeu(Zeus, Dyaus) and the Old Latin Jove. This shared etymology underpins how the concept of deity in Western spirituality was inextricably tied to the imagery and authority of the Greek and Roman ‘sky fathers.’

Political and Religious Authority Melded

If Zeus was intertwined with the Greek city-state system, Jupiter’s bond with Rome’s legal and imperial apparatus proved even more enduring. This confluence of sacred and secular has resurfaced repeatedly throughout later religious institutions.

Rome’s Template For Theocracy

Jupiter’s priests (flamines) and his principal temple on the Capitoline strategically merged civic order with divine will. Emperors, adopting the title “Pontifex Maximus,” laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the papal system of the Vatican City, where the Pope holds both spiritual and evident political sway.

In medieval France and England, monarchs claimed divine right by citing both Old Testament precursors and aligning themselves with the legacy of ‘king-gods’—a principle fully realized in Coronation rites inflected by both Hebrews and Romans.

Law, Oath and Morality

The judicial morality of Zeus—the “oath-keeper” and “guest-friend supreme”—surfaced in legal thought and Christian concepts of sacred contract. Early Church fathers admonished their flock to solemn swearing by God’s name, a concept threaded from swearing ‘per Jovem’ (by Jupiter) in Roman courts to “So help me God” in modern judiciaries.

The Transformation of Religious Rites and Symbols

Religious symbolism didn’t vanish with the decline of Olympus, instead it evolved. Iconic emblems and ritual observances shaped by Zeus and Jupiter morphed to suit Christian and later religions, creating layers of cultural continuity.

Festival Adaptations

Feast days resembling the great games of Zeus survived as community sacraments, as many local festivals marking the end of harvest (once sacred to Zeus or Jupiter) were repurposed within the liturgical calendar. For example, some Southern European saints’ days coincide with prior festivals of Jupiter, maintaining processions, food-sharing, and icon parades that reflect ancient traditions.

Symbols Reused

The eagle, sacred to Jupiter, endures as a symbol of power and transcendence, found both in Eastern Orthodox Christian banners and the heraldry of post-Roman states (the double-headed eagle of Byzantium or the Holy Roman Empire). Even the gesture of clergy blessing with the raised right hand mirrors Greco-Roman dedicatory statuary, suggesting a visual grammar passed down from the days of Zeus holding his thunderbolt.

Religion, Philosophy, and the Age of Reason

The Renaissance marked another revival for Zeus and Jupiter. Humanists, immersed in Greco-Roman texts, reimagined these gods in terms of universal order, natural law, and cosmic harmony—ideas that would influence both religious and secular philosophies.

Renaissance Syncretism

Philosophers like Marsilio Ficino saw parallels between Platonic divine order and the harmony attributed to Zeus-Jupiter. Art and literature from the era, whether it be Botticelli’s “Primavera” or Shakespeare’s references to ‘Jove,’ showcased how Zeus/Jupiter remained a touchstone for the contemplation of the divine.

Deism and Enlightenment Thought

The Enlightenment’s Deists rejected supernatural revelation in favor of a rational "supreme being," invoking the clockmaker creator reminiscent of the far-seeing, sky-dwelling Zeus and Jupiter. Voltaire and other thinkers explicitly contrasted the personal God of Christian dogma with the impersonal, kinglike figurehead reminiscent of earlier Indo-European theology, underlining the philosophical persistence of these gods’ attributes.

Syncretism in the Mediterranean World

Across the vast multi-ethnic Mediterranean, the names, features, and cults of Zeus and Jupiter fused with those of local deities, resulting in intricate religious languages that would later blend with Christian practice.

Example: Isis, Serapis, and The Universal God

The cults of Isis and Serapis gained popularity in Hellenistic Egypt and Rome by associating their supreme roles with those of Zeus-Jupiter. In temples, Zeus-Ammon (the oracular Ammun of Libya) united Greek and Egyptian theological concepts, emphasizing the reach of the sky-father motif. When Christianity began conquering the same region, it did so by subtly positioning the Christian God as the one true successor to all universal sky deities.

The Catholic & Byzantine Echo

In the Christian East, Christ Pantokrator mosaics allude to Zeus's iconography—the cosmic ruler with open arms in the apse. Ecclesiastical ceremonies, the authority of bishops, and the use of luminous domes reflect rituals once held for the great thunderer, reframing the Olympian legacy as uniquely Christian.

How Zeus and Jupiter Influence Popular Culture and Neo-Paganism

Their thunderbolts may have quieted, but Zeus and Jupiter echo today in literature, films, entertainment, and revived pagan religions.

Modern Reimagination

Movies and series like “Clash of the Titans,” Rick Riordan’s “Percy Jackson” universe, and even “Wonder Woman” explicitly revive Zeus and Jupiter, showcasing their enduring narrative power as father gods, arbiters of fate, and symbols of elemental potency.

Neo-Pagan Movements

Revivalist movements—Hellenism and modern Roman polytheism—worship Zeus and Jupiter in reconstructed rites. As scholarly appreciation of ancient beliefs grows, so does a respectful engagement with these deities as archetypes of cosmic order, personal virtue, and community leadership.

Reflecting on Legacy: Zeus and Jupiter as Timeless Archetypes

Even if Christianized Europe thought it left behind the old gods, the imprint of Zeus and Jupiter was inescapable. Their archetypal resonance—as champions of justice, order, and awe-inspiring might—influences not just religions but the very frameworks through which societies imagine the nature of divinity itself.

From ancient temples to cathedral domes, from legal oaths to superhero stories, the thunderous wisdom and majesty of Zeus and Jupiter still echo, subtly guiding humanity's search for meaning, structure, and the sublime among the clouds.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts