Did Indus Valley Traders Sail the Persian Gulf

34 min read Evidence from seals, dockyards, and Mesopotamian texts suggests Indus Valley traders navigated the Persian Gulf, linking Harappa with Dilmun and Mesopotamia during the Bronze Age. (0 Reviews)

A small boat pushes off from a muddy creek in the Indus delta. Its sides are stitched with coir, seams made watertight with resin and bitumen. The crew loads baskets of glossy carnelian beads and carefully measured copper ingots, checks a skin of water, and watches the wind. They aim west, to a horizon that leads past the Makran coast, around the headlands of Oman, and into the islanded world of the Persian Gulf. Did Indus Valley traders really make this voyage — and if they did, how do we know?

The answer unfolds not from a single smoking gun, but from a constellation of clues: cuneiform tablets naming faraway lands, Indus-style seals turning up in Gulf warehouses, beads that can be traced to workshops in Gujarat, and the logic of monsoon winds. When you put the evidence together, a compelling picture emerges of Harappan mariners embedded in a wider Bronze Age network that linked Meluhha (the Indus), Magan (Oman), and Dilmun (Bahrain) with Mesopotamia. What follows is a practical, evidence-led tour through that world — what we know, how we know it, and how to think critically about the gaps.

The Indus World Meets the Gulf: What the Question Really Asks

The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), also called the Harappan Civilization, flourished roughly 2600–1900 BCE across today’s Pakistan and northwest India, with earlier roots and later transformations. Impressive cities like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa have overshadowed the fact that Harappans were also coastal people. Settlements clustered along estuaries, tidal creeks, and salt flats from Makran to Kutch — exactly the kind of landscapes that breed boatbuilders and traders.

When we ask whether Indus traders ‘sailed the Persian Gulf,’ we’re really asking several intertwined questions:

- Did Harappans build and use ocean-going boats capable of coastal and open-water passages?

- Did they maintain sustained maritime contacts with communities in Oman (Magan), Bahrain/eastern Arabia (Dilmun), and Mesopotamia?

- Were those contacts direct (Indus ships into the Gulf) or indirect (Indus goods moving via middlemen and entrepôts)?

The vocabulary matters. Mesopotamian texts refer to three key toponyms: Meluhha (usually identified with the Indus domain), Magan (Oman and perhaps adjacent coasts), and Dilmun (Bahrain and surrounding islands). The Persian Gulf was a busy corridor for all three. Our task is to determine where Harappans fit on that traffic map.

In broad strokes, the material record and textual hints converge on a story of direct Harappan participation in Gulf trade, even if not every leg of every journey was crewed by Indus mariners. Think of a braided river: multiple channels, sometimes merging, sometimes slicing their own paths. Traders adapted — taking to sea when the wind favored them, docking in Dilmun when paperwork (and profit) demanded it, and feeding goods into overland caravans when that made more sense.

Reading the Clay: Mesopotamian Texts that Name Meluhha

One of the cleanest lines of evidence comes from Mesopotamian cuneiform texts that explicitly mention Meluhha. From the Akkadian period through the Ur III and Old Babylonian eras (roughly 24th–18th centuries BCE), scribes recorded commodities, envoys, and even specialized jobs tied to Meluhha.

Highlights include:

-

The cylinder seal of Shu-ilishu, identifying him as a 'meluhha interpreter.' Roles like interpreter do not spring up in a vacuum; they reflect repeated contact with foreign language speakers. If Meluhha were merely a nebulous place-name with no direct interaction, dedicating a professional to it would be odd.

-

Administrative texts that list exotic goods associated with Meluhha: carnelian beads, shell, wood, and other high-value materials. Several of these match precisely what we find in Harappan workshops: etched carnelian beads, standardized bead sizes and drilling techniques, and shell bangles made from Indian Ocean species.

-

The famous, if debated, tradition that Sargon of Akkad 'moored ships of Meluhha, Magan, and Dilmun at his quay.' Whether this exact phrasing comes from royal propaganda or later recensions, the clustering of these three lands — and the image of their ships berthed in a Mesopotamian port — is consistent with a maritime network.

-

Gudea of Lagash inscriptions that imply materials moving from Meluhha and Magan for temple construction. They hint at a supply chain that could handle bulky cargoes, not just trinkets.

When reading such texts, method matters. A quick how-to guide for non-specialists:

- Check the tablet’s date and findspot. A text from the Ur III period (c. 2100 BCE) may reflect different trade patterns than one from Old Babylonian times (c. 1800 BCE).

- Look for repeated associations. If Meluhha consistently appears with carnelian and shell, the pattern is meaningful.

- Distinguish literary topos from administrative entries. Royal boasts exaggerate; ration lists and job titles rarely do.

- Follow the vocabulary of ships and harbors. When texts speak of boats arriving from specific lands, they’re not describing camels.

The textual record does not draw us a sailing chart. But it establishes a durable frame: Meluhha was known, it sent people and goods, and it was maritime enough to be paired with Magan and Dilmun.

Ports, Dockyards, and Harbors on the Harappan Coast

If the Indus world exported sailors, where did they launch? Archaeology points to a string of coastal and near-coastal sites, each adapted to the challenging geomorphology of tidal flats, shifting inlets, and seasonal creeks.

Key nodes include:

-

Lothal (Gujarat): Often touted for its 'dockyard' — a large, brick-lined basin with an inlet channel. The interpretation is debated, with some suggesting it was a reservoir or tidal basin. But even skeptics acknowledge Lothal’s maritime orientation: evidence of shell-working, a nearby river channel that was navigable when built, and artifacts indicating trade. The basin’s sluice-like features and spillways look engineered for water level control, which suits both boat handling and water storage in a tidal landscape.

-

Balakot and Sokhta Koh (Makran coast): Smaller settlements with emphases on shell processing and coastal resource use. Their positions along the Pakistani shoreline would have made them logical waypoints for cabotage.

-

Sutkagen Dor (on the Pakistan–Iran border): One of the westernmost Harappan sites, strategically placed to funnel goods toward the Gulf of Oman. Its location near ancient river mouths suggests a maritime role.

-

Nageshwar and other shell-working sites in Saurashtra: Deeply specialized production areas turning Indian Ocean shells into bangles and ornaments. That specialization implies strong demand from overseas consumers and a distribution mechanism to match.

-

Dholavira (Kutch): Not a port per se, but its marine shells and strategic placement on an island-like terrain within the Rann of Kutch hints at a landscape where brackish inlets once reached far inland. During the mid-Holocene, parts of the Rann were more navigable than today.

Taken together, these sites sketch out a pragmatic maritime strategy. Rather than relying on one grand harbor, Harappans exploited multiple small, flexible anchorages near production zones, feeding goods into coastal vessels that could unite shipments for longer legs. This is not unique to the Indus; it mirrors patterns in later Indian Ocean trade.

What Floated: Boats, Materials, and Monsoons

A trade route is only as real as its boats. What did the Harappans sail?

Archaeology and ethnography point to two technologies compatible with the Indus–Gulf corridor:

-

Sewn-plank boats: Planks with edge holes stitched together using coir or other fibers, sealed with resin and bitumen. This technique persisted in western India and Oman into the historical period. Excavations in Oman have yielded bitumen with reed and fiber impressions from boat caulking. The method is ideal for curved hulls that can handle choppy coastal seas.

-

Reed and bundle boats: Suitable for rivers and deltaic waters, often sealed with bitumen. Impressions of reeds in bituminous lumps from South Asian and Gulf contexts suggest riverine and nearshore craft used this approach. While such boats are less rugged for open water, they fit the Indus delta’s creeks and may have served as feeders to sturdier coastal vessels.

Propulsion and navigation took advantage of monsoon rhythms:

- The northeast monsoon (roughly November–February) brings winds from the continent toward the Arabian Sea, favoring westbound voyages from the Indus and Gujarat to Oman and the Gulf.

- The southwest monsoon (roughly May–September) reverses that flow, favoring eastbound returns.

Sailors could combine these seasonal winds with the safety of cabotage: hugging the coast from the Indus delta along Makran, rounding Ras al-Hadd, and entering the Gulf. Distances between anchorages — Sonmiani, Ormara, Pasni, Gwadar, Chabahar, then up toward Muscat and the Strait of Hormuz — are manageable for small craft. With careful timing, even plank-built boats of modest size could complete a circuit in a year, pausing for trade and repairs.

The material trail supports this: bitumen residues, hull-sealant recipes compatible with what we know of local resources, and regional boatbuilding continuities. While no Harappan hull has been found intact, the confluence of craft evidence, coastal settlement patterns, and practical wind regimes strengthens the case for regular maritime traffic.

Fingerprints of Trade: Artifacts that Traveled

Artifacts act like shipping invoices. The most persuasive are those that are technologically distinctive or geochemically traceable.

-

Etched carnelian beads: Found in Mesopotamian contexts, these beads show a characteristic white design etched into a red-orange carnelian body using alkali treatment. Microscopic drill marks and manufacturing sequences match Harappan workshops in Gujarat. Their presence in sites far west of the Indus indicates trade in finished luxury goods.

-

Standardized weights: The Indus developed a binary-geometric weight system with precise ratios. Weights found outside the Indus sphere that match these standards suggest merchants carried not only goods but also their measuring systems. In marketplaces, weights are a cultural signature; you bring your own standards if you intend to trade on your terms.

-

Gulf-type circular seals: Round, stamp seals found in Dilmun and Oman sometimes carry Indus-like motifs or script signs. They represent a hybrid administrative toolkit, likely reflecting Indus merchants operating in Gulf ports and adapting to local sealing conventions.

-

Shell artifacts: Species like Turbinella pyrum (chank) and other Indian Ocean shells appear in Mesopotamian contexts as worked items. The raw materials and the drilled and polished forms parallel Indus production lines.

-

Copper and stone: Oman (Magan) was a major source of copper in the 3rd millennium BCE. Trade likely ran both ways: copper moving east to the Indus, crafted ornaments and textiles moving west. Geochemical studies suggest mixes of sources, but an Omani component in Bronze Age copper consumption in the wider region is consistent. Meanwhile, lapis lazuli from Badakhshan traveled through multiple corridors; Indus settlements like Shortugai in Afghanistan hint at inland links that could feed maritime routes.

It’s not merely the presence of these objects but their clustering that matters. Sites in Bahrain and Oman show concentrations of Indus-style goods during the same centuries that texts highlight Dilmun and Magan. That synchronicity — backed by stratigraphy and radiocarbon ranges — supports a living, breathing trade system rather than one-off curiosities.

The Gulf Triangle: Dilmun, Magan, and Meluhha as a Network

Picture the Gulf as a triangle of specialization:

-

Dilmun (Bahrain and adjacent coasts) functioned as an entrepôt. Excavations at Qal'at al-Bahrain reveal administrative buildings, seals, and storerooms aligned with a brokerage role. Texts cast Dilmun as a waystation for goods between the Gulf and Mesopotamia.

-

Magan (Oman) supplied copper and hosted coastal communities with boatbuilding and repair capacity. Archaeological phases like the Umm an-Nar period (c. 2700–2000 BCE) show monumental tombs and settlements connected to maritime trade. Sites such as Ras al-Jinz and those near Muscat have produced finds suggesting contact with South Asia.

-

Meluhha (Indus) exported finished ornaments, shell products, beads, textiles, and possibly timber or ivory. Its merchants brought not only commodities but also systems of measurement and sealing.

In this framework, Indus boats need not have sailed into every Mesopotamian harbor to be significant Gulf players. A plausible scenario is that Harappan ships regularly reached Dilmun, where bilingual intermediaries handled onward distribution. The presence of a 'meluhha interpreter' in Mesopotamia squares neatly with such layered exchange.

At the same time, the evidence does not exclude direct Meluhha–Mesopotamia sailings in some periods. Political stability, demand spikes, and favorable winds could have encouraged skippers to bypass middlemen. Trade systems breathe; they expand and contract with circumstance.

Overland vs. Overseas: A Comparison of Routes

Harappans could move goods to Mesopotamia by land, sea, or a blend. Which was more efficient?

-

Overland (through Baluchistan and the Iranian plateau):

- Pros: Continuity of control over caravans; multiple staging points; reduced exposure to storms.

- Cons: Terrain is punishing; caravan capacity is limited; seasonal bottlenecks; higher cumulative labor costs for heavy or bulky goods like copper or timber.

-

Maritime (coastal cabotage, then Gulf sailing):

- Pros: Greater payload per vessel; winds can aid long hauls; ability to leapfrog hostile territories via sea; fewer handling steps for heavy cargo.

- Cons: Seasonal dependence on monsoon windows; navigational hazards; need for boat maintenance infrastructure; risk of wrecks.

In practical terms, light, high-value items (etched carnelian beads, finished ornaments) travel well by both modes, but bulk commodities favor the sea. If you needed to shift a ton of copper or timber, ten small vessels might replace a hundred pack animals over the same distance with fewer transshipments.

Historical analogies support this: throughout antiquity, regions with access to cheap maritime corridors usually exploited them for bulk trade, leaving caravans for items where speed, security, or terrain dictated otherwise. The Indus–Gulf corridor aligns with that logic.

A How-To Guide for Evaluating the Evidence

Archaeology thrives on cumulative proof. Here’s a concise checklist you can use to weigh claims about Indus–Gulf sailing:

-

Context, context, context:

- Was the artifact excavated in a stratified layer with secure dates, or bought on the antiquities market? Contextless objects are weak evidence.

-

Distinctiveness of the item:

- Is the object technologically or stylistically diagnostic of Harappan production (e.g., etched carnelian with specific drill signatures) or a generic form found everywhere? Diagnostic items carry more weight.

-

Scientific sourcing:

- Have materials been analyzed via petrography, geochemistry, isotopes, or residue analysis? For beads, drilling and polishing traces are informative; for metals, lead isotope ratios can point to ore sources; for bitumen, biomarkers can identify deposits.

-

Administrative systems:

- Seals and weights speak to merchant presence. A foreign measuring system found abroad is a particularly strong indicator of traders on the ground.

-

Textual triangulation:

- Do written sources from different regions corroborate patterns observed in artifacts? For example, when both Dilmun’s archaeological record and Mesopotamian texts peak with Meluhha links in the same centuries, confidence rises.

-

Settlement ecology:

- Are there coastal or riverine settlements with infrastructure suited to boats (embankments, basins, wharves), along with craft industries related to trade? This grounds maritime claims in lived landscapes.

-

Beware single-site overreach:

- A 'dockyard' without supporting trade debris is weak; a modest quay backed by seals, weights, and imported materials is far stronger.

-

Chronological coherence:

- Do the dates line up? A 19th-century BCE bead found in a 15th-century BCE Gulf context is evidence of residual material, not contemporaneous trade.

Applying this rubric to the Indus–Gulf problem yields a verdict of 'probable and recurrent maritime contact,' bolstered by multiple independent lines of evidence.

Reconstructing a Voyage: A Practical Sailing Plan circa 2200 BCE

Imagine you are a Harappan ship’s pilot planning a round trip during the Mature Harappan period. Here’s a step-by-step itinerary that respects seasonal winds and Bronze Age constraints.

Outbound (Indus/Gujarat to the Gulf) — Ride the northeast monsoon (Nov–Feb):

- Assemble cargo in Gujarat workshops: etched carnelian beads from Lothal’s hinterland, shell bangles from Nageshwar, cotton textiles dyed with madder, small quantities of ivory, and standardized weights and seals for trade.

- Move goods via riverine and creek craft to a coastal staging point — perhaps near the Indus delta or a sheltered inlet along Kathiawar.

- Choose a sewn-plank coastal vessel of 10–15 meters with a simple square or lateen-like sail, stitched seams sealed with bitumen-resin mix. Crew of 8–12.

- Leg 1: Skirt the Kori Creek and head west to Sonmiani and Ormara. Keep land in sight; anchor overnight in protected coves. Watch for rocky outcrops and shifting sandbars.

- Leg 2: Continue past Pasni to Gwadar. Trade fish oil and salt for fresh water and repair materials. Check hull stitching; reapply sealant where needed.

- Leg 3: Cross into Iranian waters near Chabahar; the coast bends south toward Jask. Choose a weather window to round Ras al-Hadd; the NE monsoon helps, but swells can be tricky.

- Leg 4: Enter the Gulf of Oman, stopping near Muscat. Here you may barter ornaments for copper blooms from Magan intermediaries. Re-provision.

- Leg 5: Transit the Strait of Hormuz, hugging the lee of islands like Qeshm. Aim for Dilmun (Bahrain) — Qal'at al-Bahrain’s harbor offers storage and brokers.

In Dilmun:

- Present seals and weights; work with bilingual agents familiar with Mesopotamian tastes and taxes. Swap part of the cargo for barley, dates, copper, and bitumen. Arrange onward carriage for some items to Mesopotamian cities by Gulf craft if your own hull is not suited for river delta navigation.

Return (Gulf to Indus/Gujarat) — Wait for the southwest monsoon (May–Sept):

- Time departure to catch fair winds east. Avoid the hot, dusty shamal periods in the upper Gulf if possible.

- Reverse the coastal hops. With a fuller, heavier boat, keep a conservative sail plan and stop more often for water. Currents can be strong around Ras al-Hadd; plan layovers accordingly.

Navigation and safety tips a Bronze Age pilot would appreciate:

- Use stars for orientation on clear nights (familiarity with circumpolar constellations and seasonal risings helps).

- Follow seabird patterns and water color changes to locate shoals and inlets.

- Carry spare lashings and corkwood floats for emergency repairs.

- If you must cross a bight, do it at dawn to maximize daylight margin for error.

This plausible itinerary underscores a key point: the route is doable with Bronze Age technology, provided mariners exploit monsoon windows and favor cabotage over heroic open-water leaps.

Climate, Rivers, and Risk: Why Timing Mattered

Ancient sailors were also climate strategists. Three environmental factors shaped the Indus–Gulf trade corridor:

-

Monsoon seasonality: Wind direction is destiny. Regular, reversible winds made a two-headed highway between South Asia and Arabia. Missing the window could trap a crew for months.

-

Sea-level and coastline change: Mid-Holocene sea levels and sedimentation altered the navigability of places like the Rann of Kutch and the Indus delta. Channels shifted; ports silted. A site that was a harbor in 2300 BCE could be a mudflat a century later. Successful traders adapted by spreading risk across multiple anchorages.

-

The 4.2 ka event (circa 2200 BCE): A period of aridity affected parts of the Old World, contributing to stresses in Mesopotamia and the Indus sphere. For trade, drought could mean lower river discharge (affecting delta channels), crop failures (altering cargo composition), and political instability (risking piracy or toll hikes). Yet maritime routes sometimes become more attractive in such times because they bypass struggling inland polities.

Understanding these dynamics helps explain both the rise and reconfiguration of Indus maritime links. Trade likely peaked when monsoon regularity, river access, and Gulf demand aligned — and slackened as environmental and social systems shifted in the later 3rd millennium BCE.

What Is Still Debated—and What Isn’t

Strongly supported:

- Harappan goods, weights, and administrative practices reached the Gulf and Mesopotamia.

- Dilmun and Magan played intermediary roles in a network that repeatedly references Meluhha.

- Maritime technology in the region (sewn-plank boats, bitumen caulking) was sufficient for sustained coastal and Gulf sailing.

Actively debated:

-

The Lothal 'dockyard' interpretation. While it plausibly functioned in a maritime system, scholars continue to contest whether it served primarily as a harbor basin, a reservoir, or both across phases.

-

Frequency and directness of Indus hulls in Mesopotamian ports. Did most goods move via Dilmun brokers, or did Indus boats routinely nose into river mouths like those of the Euphrates and Tigris? The texts hedge, and the archaeology allows both scenarios at different times.

-

The extent of Omani copper in Indus metallurgy. Compositional studies are ongoing; the picture probably involves mixed sources and changing supply chains.

Methodological cautions:

- Beware conflating 'Meluhha' with the entirety of the Indus world at all times. The term likely shifted in scope and may have been used broadly from the Mesopotamian perspective.

- Resist the lure of singular explanations. A braided network can carry truth in its complexity: some voyages direct, many via hubs, choices tuned to risk and return.

Museums, Sites, and Further Reading: See the Story Yourself

You can ground this story in objects and places:

-

India and Pakistan:

- National Museum, New Delhi: Indus seals, beads, and weights that showcase Harappan administrative sophistication.

- Archaeological Site Museum, Lothal (Gujarat): Displays on the basin and craft production; walk the brick-lined structures and judge the harbor debate for yourself.

- National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi: Artifacts from coastal sites; context for Makran’s maritime world.

-

Gulf region:

- Bahrain National Museum and the fort at Qal'at al-Bahrain: Dilmun seals, storerooms, and a harbor landscape.

- National Museum, Muscat (Oman): Exhibits on the Umm an-Nar period, copper trade, and early seafaring.

-

Global collections:

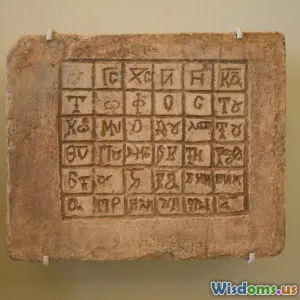

- The Louvre and the British Museum: Cuneiform tablets referencing Meluhha, cylinder seals, and administrative texts. Look for the Shu-ilishu seal and Ur III administrative tablets.

Suggested reading to deepen your evaluation toolkit and narrative sense:

- J. M. Kenoyer on the Indus craft and trade systems: detailed analyses of beads, weights, and workshops.

- Gregory Possehl on Indus chronology and regional diversity: critical for understanding how coastal and inland spheres connected.

- H. P. Ray on early Indian Ocean trade: contextualizes maritime patterns beyond the Indus.

- Laursen and Steinkeller on Babylonia’s long-distance trade: a rigorous treatment of texts on Dilmun, Magan, and Meluhha.

- D. T. Potts on Arabia’s archaeology: the material basis for Magan and Dilmun’s roles.

Practical tips for a museum visit:

- Bring a pocket notebook and sketch the shape and size of weights; note ratio regularities.

- Compare drill holes on beads under magnification (many museums provide images): straight vs. tapered holes tell you about tool types.

- Read labels critically: when a text says 'probably from the Indus,' ask what evidence underpins that 'probably.'

A final thought for those who love field method: coastal archaeology is perishable. Tides eat shorelines; deltas migrate. Underwater and intertidal surveys along the Makran and Kutch coasts are still in their infancy compared to terrestrial digs. As those methods advance, expect sharper pictures of jetties, anchors, and perhaps, one day, a Harappan hull.

The question that launched this voyage — did Indus Valley traders sail the Persian Gulf? — does not end with a courtroom yes or no. But if we read the clay, walk the shorelines, and weigh the beads, a strong, seaworthy answer takes shape. Harappan merchants were not merely city-dwellers behind baked-brick walls; they were boatmen timing monsoons, brokers stamping seals in island warehouses, and innovators who turned coastlines into corridors. On winter mornings when the northeast wind stiffens, you can still imagine their stitched hulls nosing west, the Persian Gulf ahead and a world of exchange beyond.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Indus Valley Civilization

Popular Posts