Did the Printing Press Truly Democratize Literature for Everyone

8 min read Exploring whether the printing press truly made literature accessible to all across history and society. (0 Reviews)

Did the Printing Press Truly Democratize Literature for Everyone?

Introduction

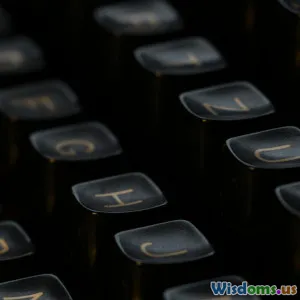

Imagine a world where each book was painstakingly copied by hand, accessible only to the elite few. Before the mid-15th century, literature was a luxury reserved mostly for clergy, nobility, and scholars. The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440 is heralded as a turning point in human history. It initiated a mass production of books, often celebrated as the great equalizer that put literary knowledge into the hands of everyone.

But did the printing press truly democratize literature? Or are there overlooked social, economic, and cultural complexities that tempered its promises of universal access? To gain a clear understanding, it's essential to trace the printing press’s impact through history, analyze who benefited most, and appreciate the barriers still in place.

The Printing Press: A Marvel of Its Time

Johannes Gutenberg’s masterpiece—the movable type printing press—slashed the effort and time to create books. Prior to this, scribes manually copied texts, a slow and expensive process limiting print runs to handfuls of manuscripts.

The Gutenberg Bible, printed circa 1455, showcased the technology's potential. It set a precedent: books could be mass produced, cheaper, and disseminated across cities and countries rapidly. Scholars point out that by 1500, around 20 million volumes existed in Europe alone, a dramatic increase from prior centuries. This proliferation is often cited as the starting gun for the Renaissance, Reformation, and the eventual Scientific Revolution.

The Promise of Democratization

To understand democratization in literature, we must define what it entails: broad accessibility across all societal segments regardless of class, gender, or geography.

Several arguments underscore how the printing press broadened literary horizons:

-

Increased Literacy Rates: The availability of books encouraged education. Literacy rates in Europe increased over subsequent centuries—from no more than 10% in early 1500s to upwards of 50% in the 18th century in some regions.

-

Spread of Vernacular Literature: Printing helped disseminate texts in local languages (vernaculars) rather than Latin, making literature understandable to the common folk.

-

Diverse Genre Production: From religious tracts and scientific manuals to poetry and pamphlets, printed works now reached beyond sacerdotal or aristocratic interests.

-

Information Sharing: It fostered public discourse, fueling movements like the Protestant Reformation through widely circulated pamphlets challenging the status quo.

Limitations and Realities: Who Truly Had Access?

Despite these advances, democratization was far from absolute.

Economic Constraints

Books remained commodities.

-

The early printed books, while cheaper than manuscripts, were still expensive. A Gutenberg Bible could cost as much as a skilled craftsman's annual income.

-

Booksellers issued subscription schemes or circulating libraries for broader use, but cost limited availability to urban centers and wealthier classes.

-

Many peasant and rural populations remained effectively excluded due to poverty.

Literacy Gaps

-

Literacy was not universally spread. Women, lower-income persons, and rural communities were less likely to be literate.

-

Educational institutions and formal schooling were rare for marginalized groups well into the 19th and 20th centuries.

Censorship and Control

-

Political and religious powers often censored printed content. For example, the Catholic Church heavily regulated printed materials post-Reformation.

-

Governments controlled licenses for printers, sometimes restricting what topics could be printed. This limitation shaped access to information and diversity of ideas.

Geographic Disparities

-

Major Western European cities benefitted most initially, while vast regions globally had minimal exposure to printing technology until centuries later.

-

In Asia and Africa, printing processed was introduced noticeably later and faced different challenges, thus the democratization effect varied widely.

Case Studies

Protestant Reformation and Print

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were rapidly disseminated due to the printing press, sparking religious debates and reform across Europe. This powerful use of print greatly broadened religious content access beyond clergy, a clear form of democratization among certain Christian communities.

Literacy in Colonial America

The printing press arrived in colonial America in the 17th century, facilitating pamphlet literacy including revolutionary ideologies. However, native populations, enslaved people, and women saw limited benefit due to systemic educational deprivation.

Victorian England's Circulating Libraries

In 19th century England, lending libraries offered affordable book access to the growing middle class, expanding literature reach beyond elites but still primarily benefiting literate urban populations.

Modern-Day Reflections

Today, the democratization of literature continues with digital technology. E-books and the internet vastly increase access. However, echoing historic barriers, issues remain with digital divides and censorship.

The printing press’s legacy is crucial: it set the foundation for expanded literacy and literary availability. Yet, evaluating 'democratization for everyone' requires acknowledging persistent inequalities along economic, educational, and societal lines.

Conclusion

The printing press was undeniably transformative, sparking a literary explosion previously unimaginable. It laid powerful groundwork toward democratizing literature, reducing costs, and spreading vernacular texts.

However, claiming full democratization overlooks crucial historical realities. Access was fundamentally limited by economic means, literacy levels, geographic remoteness, and restrictive censorship.

This nuanced understanding challenges us to recognize that access to knowledge is an ongoing struggle. The printing press initiated democratization—it didn’t perfect it. As society advances, reflecting on these historic lessons can inform efforts to overcome persistent barriers in making literature truly universal.

The story of the printing press invites us to remain vigilant and creative, striving toward a world where literature and knowledge indeed belong to all.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts