How Irrigation Transformed Life in the Fertile Crescent

14 min read Discover how irrigation revolutionized society, agriculture, and urban development in the Fertile Crescent—the cradle of civilization. (0 Reviews)

Introduction: The Cradle Made Possible by Water

Imagine a vast expanse where harsh deserts meet lush river valleys—a geographic paradox at the heart of early human history. This is the Fertile Crescent, often hailed as the 'Cradle of Civilization.' How did life not only survive but thrive here thousands of years ago? The secret was not just the mighty Tigris and Euphrates rivers but the ingenious ways humans harnessed their power. Irrigation—the deliberate channeling and management of water—transformed the Fertile Crescent and fundamentally altered the course of human society.

This article delves into the revolutionary changes brought forth by irrigation in the Fertile Crescent. Through innovations in water management, communities turned unpredictable floods into agricultural abundance, laid the groundwork for urbanization, fostered vibrant economies, and seeded the roots of civilization as we know it. The story of irrigation here is not just a tale of agricultural innovation, but a testament to humanity’s creativity and ambition.

The Environmental Canvas: Rivers, Floods, and Opportunity

Geography and Natural Features

The Fertile Crescent stretches in a broad arc from the eastern Mediterranean coast, through present-day Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, down to the Persian Gulf. Its distinguishing feature is its two great rivers—the Tigris and the Euphrates. Together with the Nile further west, these rivers created rich alluvial plains amid otherwise arid surroundings.

Yet, these rivers posed as much peril as promise: Unpredictable seasonal flooding alternated with hot, dry summers. While annual floods deposited nutrient-rich silt onto floodplains, their timing and extent were unreliable. Without intervention, droughts could parch crops while floods could wash entire settlements away.

Early Agricultural Roots

Archaeological findings from sites like Jericho and Çatalhöyük indicate sedentary settlements and the domestication of wild grains well before the advent of irrigation. However, these early societies often struggled against severe, natural limitations.

“It soon became apparent that control over water resources would be decisive for sustained agricultural productivity.”

Knowledge of rainfall patterns, topography, and river behavior became as valuable as crop selection itself. This environmental backdrop set the stage for the leap from subsistence living to organized agriculture, enabled by irrigation.

The Dawn of Irrigation: Innovations that Changed Everything

Early Irrigation Techniques

Historical and archaeological evidence suggests that irrigation developed gradually. By around 6000 BCE, communities in southern Mesopotamia (part of modern-day Iraq) began constructing basic irrigation canals using clay-lined channels to divert river water into their fields. Shadufs (bucket lifts), dikes, and simple reservoirs followed.

Key Irrigation Methods:

- Canal Networks: Often dug by hand, these diverted water from riverbanks to adjacent fields over several kilometers.

- Levees and Embankments: Controlled floodwaters, minimized riverbank erosion, and helped exclude saline groundwater.

- Basin Irrigation: Fields were divided into basins, flooded at key times, then drained to prevent waterlogging.

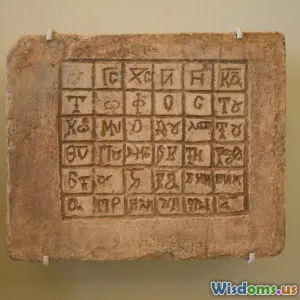

Case Study: The Sumerians of Southern Mesopotamia

The Sumerians, renowned for constructing the world’s first cities such as Uruk and Ur, perfected vast canal systems by the third millennium BCE. Cuneiform tablets from this period record not only the technical details—such as measurements and flow control—but also the legal frameworks for managing access and maintenance.

"The Sumerians’ ability to control and share water equitably was a prerequisite for the emergence of their city-states." – Samuel Noah Kramer, History Begins at Sumer

Transforming Agriculture

Irrigation allowed southern Mesopotamia to become the world’s first true breadbasket:

- Crop Yields Multiplied: Consistent water supply meant two or even three harvests per year.

- Diversification: Beyond barley, farmers grew wheat, flax, dates, and even garden vegetables—supporting larger, healthier populations.

- Food Surpluses: Enabled grain storage, trade expansion, and the growth of non-farming professions (priests, merchants, artisans).

Societal Transformation: From Villages to Great Cities

Population Growth and Urbanization

Efficient irrigation supported unprecedented population booms. As harvests increased in reliability and scale, families could settle in larger, more permanent communities. Over centuries, these expanded into bustling urban centers.

Examples:

- Uruk and Ur (c. 4000-2000 BCE): Among the world’s earliest true cities, both sat astride intricate canal networks spanning tens of kilometers.

- Babylon: Grew from a small Akkadian settlement into a metropolis, bolstered by command of sophisticated river controls.

By 2500 BCE, the Sumerians had built more than twenty city-states in southern Mesopotamia alone—each an organizing hub for its surrounding agricultural hinterlands.

Rise of Centralized Authority

Irrigation’s complexity necessitated communal cooperation and centralized oversight. The need to allocate water fairly, clean canals, and manage disputes catalyzed the evolution of bureaucratic government. It drove the recording of legal codes—the earliest in history, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu and later Hammurabi’s Code (c. 1754 BCE), included sections specifically governing water rights and canal maintenance.

“Without communal action to maintain and expand canals, both towns and crops would wither.”

Officials known as ensi or lugals (kings) presided over massive labor forces, a precursor to the vast royal projects that would shape future civilizations. The interdependence born of shared water resources forged bonds—and conflicts—that underpinned early social hierarchies.

Birth of Specialized Professions

Freed from the demands of full-time subsistence farming, larger segments of the population could pursue other work. This led directly to specialization—as artisans, scribes, traders, and priests—ushering in dramatic technological, cultural, and economic advances.

- Artisan Guilds: Produced fine textiles, pottery, and metallurgy goods for local and distant markets.

- Scribes: Kept irrigation and yield records, ushering in literacy and the birth of writing systems.

- Priests: Mediated between communities and their gods, who were often associated with rivers and fertility.

Economic Flourishing: Trade, Wealth, and Cultural Advancement

Boosting Trade and Regional Influence

With surplus food and value-added goods, Fertile Crescent societies expanded their influence. Irrigated fields lined not only the Tigris and Euphrates but also the Orontes, Khabur, and, later, parts of the Nile Delta. This abundance catalyzed far-reaching trade:

- Grain and Dates for Timber and Precious Metals: Mesopotamia, for instance, had limited access to wood and minerals, but through trade with Anatolia (modern Turkey) and the Iranian plateau, city-states acquired tin (for bronze), stone (for tools and statues), and logs to build ships.

- Uniform Weights and Measures: Standardized to facilitate commerce between diverse regions.

Cultural Exchanges & Technological Progress

Irrigation also connected disparate societies:

- Ideas, Languages, and Religions: Traveled the breadth of the Fertile Crescent’s trade routes, adding to cultural complexity.

- Technological Diffusion: Egyptians borrowed Mesopotamian canal models; later societies throughout Central and South Asia improved irrigation from precedents set here.

The abundance produced by irrigation funded not just trade but also monumental architecture (ziggurats, temples), literature (the Epic of Gilgamesh), and advancements such as the wheel and the plow.

Environmental Challenges: The Double-Edged Nature of Irrigation

Salinization and Ecological Costs

If irrigation represented a leap forward, it also manifested unforeseen drawbacks. Over centuries, excessive irrigation without proper drainage led to salt accumulation in the soil (salinization), reducing crop fertility dramatically. By 1800–1700 BCE, parts of southern Mesopotamia experienced significant agricultural decline.

Data Point:

- Excavations at Nippur show barley yields dropped by over 40% in some districts during periods of high salinity. (Jacobsen and Adams, Salt and Silt in Ancient Mesopotamian Agriculture)

Societies responded by switching from wheat to more salt-tolerant barley, rotating field locations, or migrating to new territories. Still, ecological stress contributed to the decline of several great cities.

Social and Political Instability

Irrigation also heightened intercommunal competition. With population pressures and shifting river courses, conflicts over water rights fueled wars between city-states:

"The importance attached to control of water by states and statesmen led some scholars to speak of 'hydraulic empires.'" — Karl Wittfogel, Oriental Despotism

Such fights often realigned political boundaries and hastened social upheavals.

Enduring Legacy: Lessons and Relevance Today

Continuity and Adaptation

Despite challenges, the organizational models, technical methods, and social insights drawn from the Fertile Crescent profoundly shaped later civilizations and resonate today. Many modern irrigation layouts—whether in Egypt’s Nile Valley, the Indus basin, or California’s Central Valley—owe much to these ancient innovators.

Lessons for a Modern World

The Fertile Crescent’s experience offers vital lessons for sustainable resource use:

- Community Management and Equity: Success depended not just on technology, but fair distribution, shared maintenance, and legal protections.

- Environmental Awareness: Recognizing early how salinization and mismanagement could lead to disaster.

- Resilience and Adaptation: The ancient Mesopotamians constantly innovated, altered crop choices, and even relocated when needed.

Inspiring Innovation

Above all, the story of irrigation here demonstrates the enduring power of collective human creativity in the face of environmental challenge. By devising irrigation, the peoples of the Fertile Crescent created the conditions for urban life, literacy, science, governance, and cultural blossoming—paving the way for all later civilizations.

Conclusion: Water’s Silent Revolution

The tale of the Fertile Crescent is not merely a chronicle of kings and empires—it is the story of how ordinary people banded together to transform unpredictable rivers into lifeblood for their communities. Through irrigation, they unlocked nature’s bounty, spawned the world’s first cities, and set humanity on a path that would lead to unimaginable achievements. When we study the arc of early history, we find that the ability to channel water was every bit as revolutionary as the invention of the wheel or the discovery of fire.

Understanding how irrigation changed life in the Fertile Crescent gives us not just insight into our past, but vital reminders for our own future—where fair water management, technological ingenuity, and stewardship of the land remain as critical as ever.

References

- Kramer, S. N. (1981). History Begins at Sumer. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Jacobsen, T., & Adams, R. M. (1958). Salt and Silt in Ancient Mesopotamian Agriculture. Science, 128(3334).

- Simpson, S. J. (2017). Mesopotamian Irrigation and Agriculture. In Encyclopedia of Ancient History.

- Wittfogel, K. (1957). Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power.

- Wilkinson, T. J. (2013). Archaeological Landscapes of the Near East.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts