Why Babylonians Mapped the Stars Before the Greeks

13 min read Discover how the Babylonians preceded the Greeks in charting the stars and their impact on later astronomy. (0 Reviews)

Why Babylonians Mapped the Stars Before the Greeks

Gazing into the night sky is as ancient as humanity itself. Yet, before the philosophical ponderings of the Greeks took root in the annals of Western civilization, another society meticulously mapped the heavens – the Babylonians. Their attention to the patterns of stars and planets was not mere stargazing; it was an audacious, systematic attempt to understand the cosmos, one that would shape astronomy for generations. But why did the Babylonians chart the stars long before Aristotle walked under them? Let’s dive into the profound drivers, achievements, and legacy of Babylonian stargazing.

The Babylonian Urge to Measure the Heavens

Unlike the Greeks, whose fascination with the cosmos often began with geometric or philosophical questions, the Babylonians’ astronomical curiosity revolved around practical needs and deeply held beliefs. The land between the rivers, Mesopotamia, was defined by daunting uncertainties—floods, droughts, and celestial portents that seemed to govern fate itself.

A Land at the Mercy of the Skies

Farming sat at the heart of Babylonian civilization. Success or failure hinged upon the rhythm of the seasons and the unpredictable moods of the weather. From as early as the 2nd millennium BCE, priests observed the sun, the moon, and the bright wanderers we now call planets. Their goal wasn’t just curiosity—it was survival and social order.

- Calendar Creation: Regular observations enabled the Babylonians to develop one of humanity’s first lunisolar calendars. The timing of ceremonial festivals, river management, and agricultural planning all depended on such calendrical precision.

- Divination and Omens: Star patterns, particularly strange phenomena like eclipses or planetary conjunctions, were interpreted as messages from the gods. The Enuma Anu Enlil, a series of massive cuneiform tablets, catalogued thousands of omens based on celestial events.

Institutionalized Astronomy

Unlike in many cultures where knowledge was private or sporadic, Babylonian astronomy was institutionalized. Scholars worked in temples, passing expertise from one generation to the next, carving records into lasting clay tablets. This bureaucratic, organized focus fostered continuity and meticulous data collection lasting over a thousand years.

Example: The city of Babylon itself was crowned by the great ziggurat, Etemenanki, which was likely a platform for sky-watching and ritual, merging the sacred with the scientific.

Techniques and Innovations: Cuneiform Science in Action

The Babylonians pioneered techniques that would astonish even the Greeks, laying the foundations for the scientific study of the sky.

Recording the Movements

While earlier cultures noted the seasons, Babylonian astronomers systematically documented the positions, risings, settings, and conjunctions of celestial bodies. Round after round, every major planet (“wandering star”) received careful attention in their cuneiform diaries. This recordkeeping spanned centuries—something unmatched in scale and accuracy for its era.

Arithmetic, Not Geometry

A key distinction: the Babylonians wielded arithmetic as their main tool, forgoing geometry until much later. For example, they developed arithmetical algorithms to forecast phenomena, using addition, subtraction, and patterns in cycles to compute when Venus would appear or how the moon would move.

- Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa: This famous 7th-century BCE clay tablet lists the dates of the rising and setting of Venus over several years. Such datasets allowed predictions of future events—and ultimately inspired the Greeks to reach for similar records.

The Zodiac and Division of the Sky

While today’s zodiac signs are best known through Greek and Roman astrology, their roots lie even deeper. By the late 5th century BCE, Babylonians had already divided the sky into 12 equal “signs,” corresponding with constellations along the ecliptic. Their precise sidereal division became the blueprint for Western astrology and astronomy alike.

Lunar and Planetary Theory

Babylonians even solved the vexing problem of predicting lunar eclipses and the wandering of the moon using a sophisticated zigzag numerical scheme. Conceptually, this is a form of early mathematical modeling, using stepwise or constant rates—far in advance of anything in contemporary Greece until Hellenistic times.

Fact: Their methods allowed them to predict lunar eclipses—key omens in Mesopotamian belief—with impressive regularity, helping to cement the priesthood’s authority.

The Babylonian Worldview vs. Greek Philosophy

Understanding why the Babylonians pioneered star mapping before the Greeks requires exploring their mindset—and why Greek thinkers took such a different path.

The Role of Religion and Ritual

For Babylonians, the skies were not abstract; they were the literal parchment upon which gods wrote humanity’s fate. Nightly observations weren’t primarily for understanding physical laws, but for interpreting divine signs. The Greeks, centuries later, would attempt to explain why the heavens moved as they did. But for the Babylonians, what the heavens portended for people was the central question.

Insight: This practical goal steered Babylonians toward gathering immense volumes of empirical data, suitable for forecasting patterns—but led them to eschew more theoretical or geometric questions boycotted by their Greek counterparts.

Greeks: Philosophers or Observers?

When science blossomed in the Greek world, it aligned less with crafts or administration and more with philosophical inquiry. Thales of Miletus, Pythagoras, and later Plato debated not just what happened in the sky, but why it might appear that way—leading to the rise of celestial models and geometrical speculation. However, until the rise of the Hellenistic tradition (post-Aristotle), Greek observations were scattered and less systematic.

Comparison:

- Babylonians: Religious, state-driven, systematic recordkeeping, arithmetic-based.

- Greeks: Philosophical, explained natural phenomena, geometric models, incrementally systematic.

How Babylonian Techniques Shaped Astronomy’s Future

Despite their pursuit being motivated by divination and ritual, Babylonian methods transformed the course of global astronomy. Their influence was so profound that even the Greek astronomers—often credited as initiators of Western science—borrowed Babylonian data and techniques.

The Great Transmission

When Alexander the Great conquered Mesopotamia in the 4th century BCE, Babylonian astronomical records traveled west to Greece and Egypt. Centers like the Library of Alexandria became melting pots for this accumulated knowledge. Greek astronomers, like Hipparchus and Ptolemy, incorporated centuries of Babylonian planetary logs, eclipse records, and calculations into their own frameworks.

Example: Babylonian calculations of lunar motion—as preserved in Ptolemy’s later Almagest—set the standard for precision up through Late Antiquity.

Legacy in Timekeeping and Cosmology

From the use of a 360-degree circle (originating in Mesopotamian sexagesimal math) to the organization of hours and minutes, Babylonian insights remain woven into contemporary timekeeping and star-mapping. Even modern terms like “zodiac” and “planet” emerge from their trailblazing system.

Fact: The Babylonian method of interpolating between past observations to project future celestial events foreshadows techniques in today’s quantitative sciences.

Surprising Archaeological Discoveries

Ongoing excavations across Iraq and Syria continue to shed light on just how advanced—and collaborative—astronomy was in ancient Babylon.

The Mul.Apin Compendium

Among the greatest finds was the Mul.Apin series—two vast tablets documenting the stars, the risings and settings of constellations, and methods for predicting lunar eclipses. They act almost like an instructional manual for a new astronomer, containing:

- Star lists and identification keys.

- Procedures for measuring time at night with a water clock.

- Lengths of daylight throughout the year.

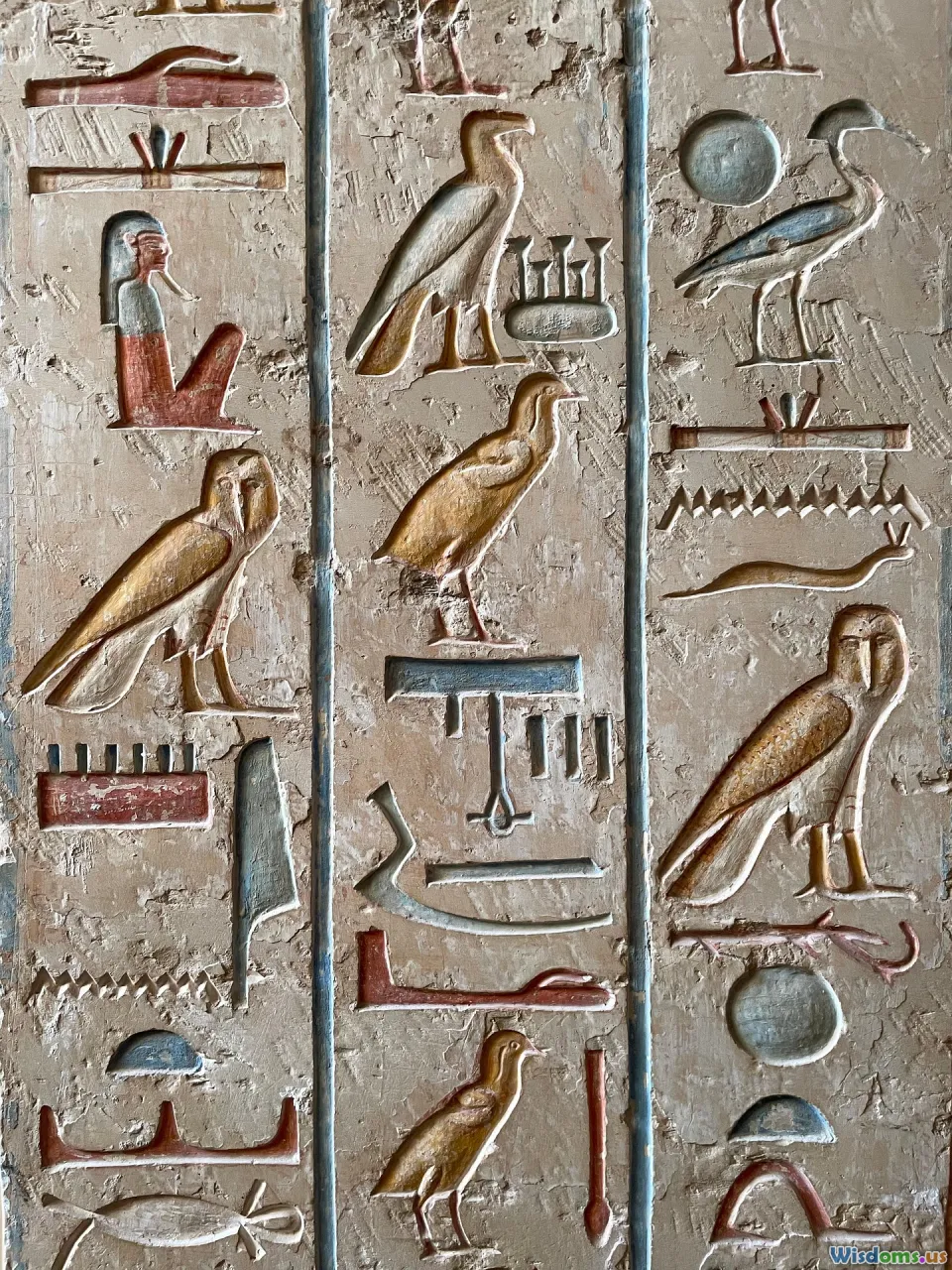

The Clay Tablets: Ancient Hard Drives

Unlike fragile papyrus, cuneiform tablets resist time. Thousands have been preserved, some still unread in world museums. This survival has given modern scholars direct insight into the mindset, techniques, and worldview of Babylonian scientist-priests—evidence that is often more elusive for ancient Greek astronomy, where original documents rarely survived.

International Influence

The Babylonian imperial reach facilitated cross-cultural transmission. For instance, Chaldean astronomers were highly sought after by foreign courts, from Egypt’s Ptolemies to distant Hellenistic monarchs. Astronomer-priests served as both courtiers and scientific advisors.

Lessons from Babylonian Star Mapping for Today

The Babylonians remind us that science can begin anywhere—out of necessity, reverence, or the simple urge to decode the cosmos. Their approach, governed by care, persistence, and systematic documentation, models several principles for today’s knowledge-seekers:

- Observation Before Theory: True progress starts with careful observation and recordkeeping, even before underlying reasons are clear.

- Cross-Generational Collaboration: Knowledge thrives when institutions (like temples, or today’s universities) nurture and transmit discoveries across lifetimes.

- Cultural Value of Science: Practical needs and metaphysical beliefs alike can catalyze scientific achievement.

- Global Exchange: Sharing knowledge across societies—then, as now—often creates intellectual revolutions beyond what any isolated group might achieve.

When you look up at the night sky, you trace the lineage not only of Greek thinkers or modern scientists, but of the determined, pragmatic Babylonian astronomers whose meticulous notes first mapped humanity’s place among the stars. Their legacy is etched not just in clay, but in every organized chart, calculated eclipse, and patterned prediction we still revere today.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts