Inside a City That Reduced Crime with Smart Design

30 min read Explore how a mid-sized city cut crime through CPTED, better lighting, activated streets, and data-led design—featuring before/after results, budgeting insights, and community-led maintenance. (0 Reviews)

On a steep hillside where buses once stopped short and residents counted stair steps like hazards, a silver gondola glides overhead. Below, a ribbon of outdoor escalators hums. Children dart between shaded benches. The route that used to be a gauntlet is now a commute with views. This is a city that decided safety was not only about arrests or surveillance, but about how you cross a street, how long it takes to reach a job, and whether your block tells you it belongs to everyone.

A generation ago, Medellín, Colombia was shorthand for fear. Today, it is a case study in how design can change routines, knit neighborhoods together, and with them, the odds of crime. This is not a fairy tale, nor was the shift instantaneous. It was a deliberate mix of infrastructure, public space, and governance that redesigned risk out of daily life.

The strategy that reframed crime as a design problem

Medellín’s approach is often called social urbanism. Rather than treating violence solely as a policing problem, the city asked how built form and access shape opportunity and conflict. If a hillside settlement is a 90-minute climb from a bus stop, how much time and dignity does the city steal before a person even looks for work? If the only well-lit patch is in front of a liquor store, where do teenagers gather at dusk? The strategy focused on solving those frictions.

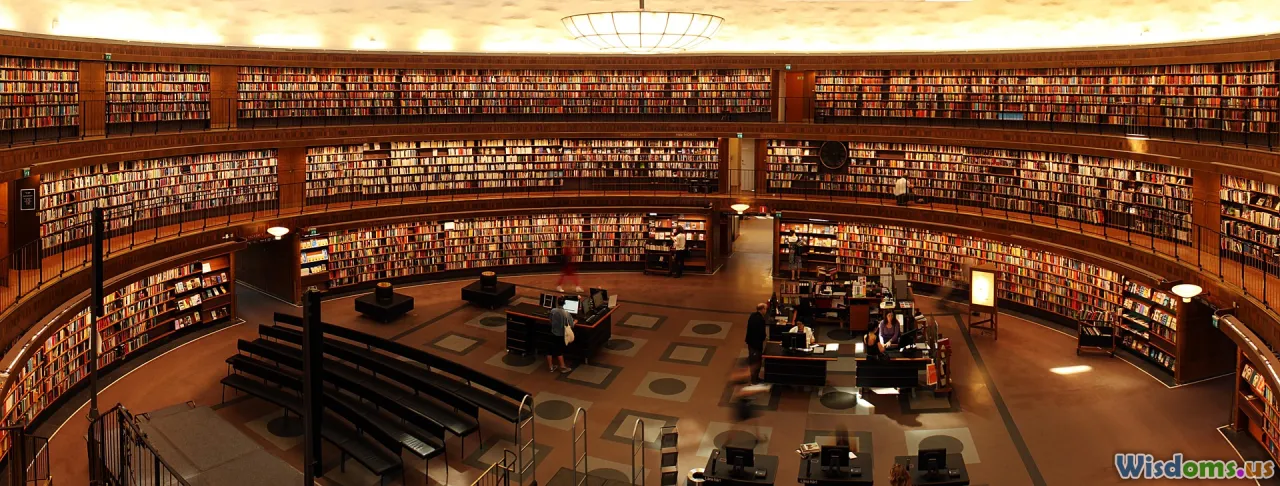

Key elements included the Metrocable aerial gondolas that connected informal settlements to the metro, the renovation and creation of library parks and small plazas, a network of improved footpaths and stairs, targeted lighting, and consistent community engagement through neighborhood-based Urban Integral Projects. The idea was simple: safer cities are ones where everyday movements are predictable, shared, and supported by design.

This reframing did not ignore policing. Medellín reformed its data use, coordinated with national security, and invested in social programs. But the signature difference was where resources went first: to the edges, slopes, and alleys where daily life happens. It was an admission that you cannot police your way out of a staircase that takes 35 minutes to climb.

Five design moves that changed daily life

Medellín deployed many projects, but five design moves illustrate how the city rebuilt its risk landscape.

- Connect isolation to opportunity

- The Metrocable lines, beginning with Line K in the mid-2000s, linked hillside comunas directly to the metro system. A trip that might have taken more than an hour with multiple transfers became a predictable 15–20 minutes in a gondola. Regular service, a single fare, and integration with the broader transit network meant a job center was no longer a distant rumor.

- The principle: fewer transfers and shorter travel times reduce routine risks and open legal opportunities, eroding incentives for predation and the territorial control that gangs exploit.

- Claim public space as civic space

- Library parks such as the striking complex in Santo Domingo Savio stood as beacons of learning, free internet, and programming. Even when one iconic building later needed structural repairs, the urban logic remained: anchor disputed areas with institutions people want to use daily.

- Smaller plazas and community rooms multiplied these anchors. Unused corners became basketball courts; leftover land around water tanks became play and cultural spaces through a program to convert utility sites into neighborhood amenities.

- Make topography walkable

- Comuna 13’s outdoor escalator system, roughly 384 meters long over six sections, cut a grueling climb to a few minutes. Stairways were widened, handrails standardized, steps regularized, sightlines opened. On steep hills, walkability is not a luxury; it is a safety technology that lowers exposure time and increases encounters between neighbors.

- Wayfinding signs made paths legible. When routes are clear, people are not forced into blind shortcuts or isolated detours.

- Light, legibility, and maintenance

- Lighting programs targeted routes to schools, transit stations, and markets. Poles were placed with careful spacing to avoid dark patches, and fixtures were selected to minimize glare. Routine maintenance plans ensured dead bulbs were replaced quickly, because a broken light is also a broken promise.

- Street numbers, block maps, and consistent signage let residents and visitors navigate without relying on informal guides. That clarity reduces the power of those who profit from confusion.

- Co-design and micro-contracts

- Through the Urban Integral Project model, the city ran neighborhood workshops that let residents prioritize small but meaningful works: a stair landing widened to fit a bench, a ramp where mothers pushed strollers, a curb cut where delivery handcarts toppled. Trusted local groups often received micro-contracts for maintenance, creating a sense of ownership.

- Co-design mitigated the all-too-common problem of pristine facilities fenced off from daily use. In Medellín, the test of a space was not how it looked on opening day but whether it filled with people on a Tuesday afternoon.

These moves sound straightforward; their power lies in compounding effects. A lit, direct path to a gondola that takes you to a job is more than a nicer walk. It rewrites the map of where it is rational to go, at what times, and with whom.

What the numbers say

Medellín’s transformation is often summarized by homicide rates. In the early 1990s, the city’s rate exceeded 300 per 100,000 residents; by the mid-2010s it had fallen to a few dozen per 100,000. While rates have fluctuated since, the long-term drop is undeniable.

Crucially, design was not acting alone. Demobilizations, changes in organized crime, and national policy mattered. But studies and municipal data suggest that neighborhoods closest to the new infrastructure and public space program saw outsized improvements in safety indicators and mobility.

Supporting evidence from other cities strengthens the case for specific design elements:

- Lighting: a randomized trial in New York City public housing found that temporary lighting towers led to about a 36 percent reduction in nighttime outdoor serious crime during the study period around treated sites. Improved lighting increases natural surveillance and reduces the cover that offenders exploit.

- Greening: in Philadelphia, a large-scale program that cleaned and planted vacant lots, with simple fencing and regular maintenance, was followed by significant reductions in gun violence around treated lots in disadvantaged areas. Researchers observed declines on the order of 20 to 30 percent in some categories, alongside drops in residents’ reported stress.

- Secure design standards: in the United Kingdom, developments built to police-certified Secured by Design standards have, in multiple evaluations, experienced roughly half the burglary rate of comparable non-certified developments. While not all contexts are identical, the pattern is clear: entry points, sightlines, and defensible space matter.

Combine those findings and a picture emerges: design that shrinks anonymity, accelerates legitimate trip-making, and celebrates shared spaces can lower both the temptation and the tactical feasibility of crime.

Street-level tactics: turning fear zones into everyday routes

If a cable car is the emblem, an alley is the test. Many cities have alleys and passages that feel unsafe because they are narrow, dark, and unprogrammed. The tactics below translate Medellín’s lessons into micro-scale moves.

A how-to for a single block or alley:

- Shrink hidden corners: round or chamfer blind corners, add convex mirrors at tight turns, and replace solid walls with perforated screens where privacy is not essential. A corner you can see around is a corner that cannot hide a person.

- Windows and facing doors: wherever feasible, add windows to ground floors that face the alley, or encourage live-work units with entries on both street and alley. More eyes, more greetings, fewer ambush points.

- Lighting hierarchy: use continuous, warm-white lighting that avoids pools of brightness separated by darkness. Offset fixtures on alternating sides to minimize shadow stripes. Ensure fixtures are reachable for maintenance without special lifts.

- Active edges: mount small tables for chess or homework near building entries; paint a hopscotch grid; add a water tap. The goal is to attract legitimate, short-stay uses; a place used by ten-year-olds at 5 pm is seldom a hotspot at 9 pm.

- Wayfinding and naming: give the alley a name on a sign and on maps. A named place is easier to reference when calling in maintenance and it signals that the space belongs to the city, not to a gang.

- Drainage and cleanliness: fix puddles, add grates, repaint regularly. Disorder cascades; water and trash are accelerants of neglect.

To choose where to start, overlay your calls for service, pedestrian desire lines, and transit stops. Then run a one-day pilot with temporary lighting, clean-up, and pop-up uses. Observe for a week. Modify permanently based on what people actually do, not what you imagined they would do.

What it cost and what it returned

Cities worry—with reason—about affordability. The headline assets in Medellín varied in cost:

- Aerial cable car lines typically cost tens of millions of dollars per line to build, with operating costs that are a fraction of heavy rail. They move thousands of passengers per hour, per direction, at speeds useful for daily commuting and with a relatively small footprint on steep terrain.

- The outdoor escalator system in Comuna 13 reportedly cost in the single-digit millions of dollars. That is a small share of a typical city’s annual capital budget, yet it transformed access for thousands of residents.

- Library parks and small plazas ranged widely but often came in at a scale that cities routinely spend on single road widenings.

Return on investment is not only in crime stats. Faster commutes boost incomes; public space raises property values while changing who feels welcome to be there; better lighting reduces traffic injuries and fear. When evaluating budgets, cities should consider (a) lifetime maintenance, not just capital, and (b) the cost of not acting: lost hours, lower labor-force participation, and the multiplier effects of fear on retail and schooling.

A practical budgeting tactic is to bundle micro-projects with one major investment. For example, when installing a cable line, reserve a set percentage for stairs, landings, and signage within a ten-minute walk of each station. The last 500 meters are where safety returns multiply.

A practical playbook for other cities

Even without hills or gondolas, the approach travels. A mid-sized city can use this phased playbook.

Phase 0: Learn the baseline

- Map the 15-minute access to jobs, school, and health clinics for each neighborhood. Identify bottlenecks that add transfers, confusion, or long detours.

- Create a composite risk map: combine police incidents, hospital injury data, school attendance dips, and 311 complaints. Look for spatial overlap.

Phase 1: Quick wins (first 100 days)

- Deploy mobile lighting to the top ten risk corridors leading to transit stops or schools. Set a maintenance hotline with a 24-hour replacement promise for failed units.

- Run alley and stair cleanups with residents; install wayfinding; name unnamed passages.

- Pilot traffic calming and safe crossings at two or three dangerous intersections near markets or schools.

Phase 2: Anchors (6–24 months)

- Build or repurpose one library, community center, or sports hub in a high-need area, paired with a small public space. Program it morning to evening with partners.

- Upgrade a key corridor with consistent lighting, paving, and storefront support grants to increase legitimate presence.

Phase 3: Network (1–5 years)

- Add a transit connection that cuts a major access gap—this might be a bus rapid transit link, a tram, or, in hilly terrain, a cable line. Focus on predictable headways and easy transfers.

- Replicate micro-upgrades within the catchment of each new station: stairs, ramps, benches, play pockets.

Across all phases, commit to co-design, transparent metrics, and maintenance contracts that fund care at least five years beyond opening day.

The tech that works (and what to skip)

There is no virtue in high-tech for its own sake. The following tools tend to deliver.

- Smart lighting with dumb defaults: adaptive systems that brighten when people are present and dim late at night can save money, but the default must be sufficient, even when sensors fail. Avoid gimmicky color changes that create glare.

- Open data on service performance: publish time-to-repair for lights, escalators, and elevators. Reliability improves when the public can see it.

- Phones, not platforms: create a light-weight reporting channel via SMS or messaging apps for outages, broken steps, or vandalism. Reward top contributors with public thanks and micro-grants for block projects.

- Minimal cameras, maximal visibility: where cameras are used, focus on clear goals such as monitoring escalation-prone spaces and coordinate with privacy policies. The design priority remains natural surveillance: people seeing other people in daily activities.

Skip complex systems that cannot be maintained locally. A dark smart pole is worse than a bright dumb one.

Pitfalls and course corrections

No city’s path is smooth. Medellín’s famous library in Santo Domingo, for instance, needed cladding repairs that took it out of service. Some years saw upticks in violence due to shifting criminal dynamics. The lesson is not that design is irrelevant, but that design must be coupled with durable maintenance and honest communication.

Other common pitfalls:

- Showcase bias: building iconic projects in visible places while neglecting the feeder network that makes them useful. Anchor projects without walkable routes are islands.

- Security-only drift: equating safety with officers alone, which can backfire if trust is low. Design should reduce the need for confrontations by making risky behavior harder and legitimate behavior easier.

- Displacement without inclusion: rising property values can push out the very residents a project aimed to help. Inclusionary housing, rental support, and tenant protections need to accompany physical upgrades.

- Participation theater: consultation sessions that do not change plans erode trust. Co-design means altering details based on lived experience, not just collecting comments.

How other places proved the principle

Medellín is not an outlier; it is a prominent example of a broader pattern.

- London and the Secured by Design framework: developments that follow standards for natural surveillance, secure entry points, and clear boundaries have consistently recorded lower crime rates, especially burglary. By designing out hiding spots and easy access, neighborhoods cut opportunistic offenses without feeling like fortresses.

- Philadelphia’s greened vacant lots: a randomized rollout of cleaning, planting, and simple fencing showed substantial reductions in nearby gun violence and improved resident mental health. The mechanism is not magic; it is routine care and occupancy that sends a message of ownership.

- New York’s lighting trial: portable, bright, well-placed lamps reduced serious nighttime crime around public housing developments. The takeaway for permanent design is to cover travel paths, courtyard entries, and parking edges evenly, with fixtures that are easy to repair.

These examples differ in budget and aesthetic, but they align on the basics: visibility, legibility, and everyday use.

The one-hour safety audit any team can run

Gather three to five people at dusk with a clipboard or phone. Pick one corridor between a transit stop and a school, market, or clinic. Score each item from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

- Continuity: can a person walk the route without stepping into the roadway or detouring into isolated areas?

- Lighting uniformity: are there dark patches between lights? Are faces recognizable at 15 meters?

- Sightlines: can you see at least 30 meters ahead without blind corners?

- Activity generators: are there legitimate uses spilling onto the route after work hours?

- Wayfinding: is every turn clearly signed? Are building numbers visible?

- Maintenance: any broken fixtures, missing steps, or frequent puddles?

- Social cues: would a teenager, an elderly person, or a parent with a stroller feel they have permission to be here?

Collect quick quotes from passersby: what would make this walk easier? Fix the top three issues within two weeks and report back to the same people. Iteration builds momentum and trust.

Metrics that matter beyond crime counts

Crime rates are vital, but they lag perception and do not capture everyday improvements. Add these indicators to your dashboard:

- Perceived safety by time of day, disaggregated by gender and age. A survey on a transit platform at 6 pm will differ from one at 9 pm; both matter.

- Footfall counts on target routes at different hours. More walkers in more hours signals resilience.

- Dwell time and diversity in public spaces: are different age groups present? Are weekday afternoons active or empty?

- Reliability metrics for escalators, elevators, and lights. Availability above 95 percent should be the goal where these systems are critical.

- School attendance along upgraded corridors. Missed days often drop when routes feel safer.

- Small business openings and evening hours along improved streets. Commerce after dark is a strong safety indicator.

Publish these metrics monthly. When something breaks, the public should see you fix it.

Voices from the hillside

In any city, the story of safety change is told in routines. A commuter who once set an alarm for predawn hours now leaves home later because the cable line’s intervals are reliable. A grandmother who avoided certain stairs at dusk now pauses on a landing bench to chat. Teenagers who used to scatter at sirens linger on a small square under a series of lamps, kicking a ball until dinner.

One community organizer remembers neighbors marking a map not with red dots for crime but with blue dots for places they would meet friends. The dots multiplied near well-lit stairs and the library park. The organizer realized the map was not just of safety, but of life—more dots meant more reasons to be outside together.

These stories are not proof in a statistical sense, but they are the texture that numbers alone cannot give. They are also a reminder: the goal is not less crime; it is more living.

Ten replicable patterns you can prototype in six months

- School routes first: pick three schools and upgrade every segment within a ten-minute walk—lighting, crossings, murals, benches, trash cans, and vendor spots.

- Transit halo: for every station or major stop, create a 500-meter halo of small improvements: stair fixes, zebra crossings, and shopfront micro-grants.

- Corner beacons: at intersections with long blocks, add corner mini-plazas with trees and seating to slow traffic and anchor social activity.

- Alley renewal: select five alleys for a full makeover—naming, lighting, art, and resident-led maintenance.

- Evening markets: pilot structured evening markets on improved streets to seed positive nighttime presence.

- Micro-libraries: swap unused kiosks for free book nooks and homework tables under lights.

- Green stitches: plant linear greenery along walls on narrow routes with integrated seating; maintain monthly.

- Shared tool sheds: provide maintenance crews and residents a local shed with basic tools and paint; supply replenished by the city.

- Safe stairs standard: adopt a detail book for stair geometry, landings every 12–16 risers, handrails both sides, drainage, and lighting placement.

- Community stewards: pay stipends to residents to walk key routes at peak times, assist elders, and report issues. It is social CCTV with humanity.

The long game: governance, contracts, and care

Design is not a project; it is a system. Sustained safety gains depend on governance choices:

- Cross-agency teams: transit, public works, parks, and safety should plan and budget together. If the transit agency builds a station, the parks department should be funded to program the plaza.

- Performance-based maintenance: contracts should specify uptime and response times for lights, escalators, and elevators, with bonuses for exceeding targets and penalties for misses.

- Transparent procurement: publish bid documents and award criteria for public space projects, prioritizing maintainable materials and local fabrication.

- Community covenants: formal agreements with neighborhood groups to co-manage spaces, backed by micro-grants and training.

- Iterative capital planning: allocate a portion of the capital budget annually for small fixes identified by data and public feedback, not just large projects announced years in advance.

Cities that treat maintenance as glamorous will win. A shiny opening day is a promise; kept promises, week after week, turn into trust.

As the sun sets on a hillside city, the small decisions are visible. Lights come on without flicker. The escalator clacks and carries. The bench is occupied by a chess game that has lasted all month, one move at a time. A gondola pulls in, doors open, doors close, someone goes to work or to home. Safety is not the absence of bad events; it is the presence of good routines. Design, done with care, makes those routines inevitable.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Urban Planning

Popular Posts