Mistakes to Avoid in Expedition Planning

32 min read Avoid critical expedition planning errors with practical checklists, risk tactics, and logistics tips to keep teams safe, compliant, and on schedule. (0 Reviews)

You can buy an ultralight tent, load perfect GPX tracks, and block two weeks on the calendar. None of that guarantees a safe or successful expedition. Major setbacks usually trace back to planning errors made months before the first step: a permit missed by a week, weather windows misread, calories undercounted, or a team dynamic left to chance. This guide unpacks the most common expedition-planning mistakes and shows you how to avoid them with practical tools, numbers you can trust, and habits that resilient teams use in the wild.

Underestimating risk complexity

Many plans treat risk like a single dial you can turn up or down. In reality, expedition risk is a mesh of objective hazards (terrain, weather), human factors (fatigue, decision bias), and logistic fragilities (permits, transport, communications). Underestimating that complexity is the root of many crises.

Actionable steps:

- Build a hazard register. For each day or leg, list discrete hazards: avalanche paths, crevasse fields, river crossings above knee height, talus slopes, heat exposure above 35 C, icefall zones, political checkpoints, and ferry cancellations. Rate likelihood and consequence on a 1–5 scale. Multiply for a quick risk priority number. Do not skip low-likelihood, high-consequence events; they are the ones that end evacuations.

- Layer controls. Use the Swiss cheese model: prevention (route choice), mitigation (rope team, helmets), detection (snowpack tests, altimeter trends), and recovery (self-rescue rigs, evac insurance). The more independent the slices, the fewer holes will line up.

- Pre-mortem session. Before departure, ask the team to imagine the expedition failed. List the plausible causes without blame. Sort by probability and impact, then add countermeasures to the plan. This surfaces blind spots faster than rosy scenario planning.

Example: On glacier traverses, parties often accept a higher daytime temperature to move after sunrise. A better control is to plan pre-dawn starts, roped travel with prusiks pre-rigged, and turnaround criteria tied to snow bridges softening (boot penetration beyond ankle = abort). This layered approach reduces both the chance and consequence of a crevasse fall.

Vague objectives and success criteria

Expeditions derail when the team is unclear on what success looks like. Summitting a peak, conducting sample collection, capturing wildlife images, or tracing a new traverse each implies different tolerances for delay, risk, and weight.

Avoid by:

- Writing SMART objectives. Example: Collect 12 water samples from river transects A–D, each at 0, 5, and 10 km from the glacier snout, within 9 field days. Include sample volumes, preservation method, and shipping timeline.

- Defining a shared hierarchy of goals. If the primary aim is scientific sampling, a missed summit is not a failure. Codify trade-offs in a one-page mission statement packed at the top of the field manual.

- Setting explicit decision points. Turnaround times, go/no-go winds (e.g., 50 km/h at 7,000 m = no summit push), river levels (waist-deep at noon = return with a dawn attempt), and illness thresholds (two team members with GI symptoms = rest day and rehydrate).

Case insight: On Aconcagua, weather windows can close for a week. A team that embeds the rule summit attempts only with three consecutive days of forecasted 500 hPa winds below 30 kt will either climb smart or wait smart; without such criteria, they drift into plan continuation bias.

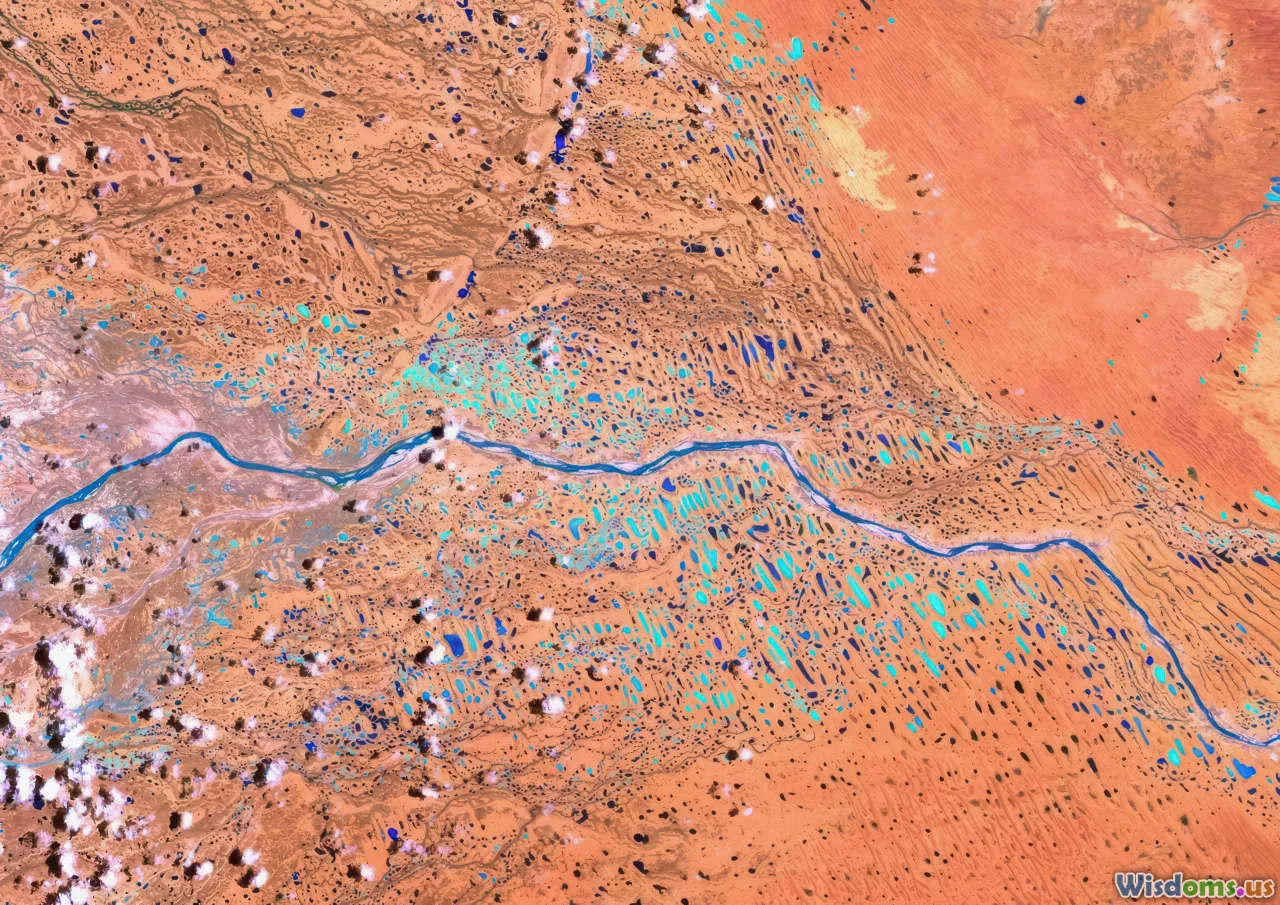

Skimping on reconnaissance and mapping

Relying on a single map app is a planning trap. Terrain looks different at expedition scale than it does on a 6-inch screen.

Make reconnaissance multi-source:

- Maps and data. Combine 1:25,000 topographic maps, recent high-resolution satellite imagery, open-source DEMs to create slope-angle heatmaps (critical for avalanche assessment), and hydrology layers to anticipate crossings and catchments.

- Local imagery and reports. Scan trip reports from the last two seasons, talk to guides, rangers, or researchers. Ask what surprised them. Pay attention to new landslides, glacier retreat opening moats, bridges out, or new livestock fences.

- Route cards. For each leg, write distance, elevation change, expected pace range, hazards, escape routes, and water reliability. Print them. Batteries die; your brain does too when cold and hypoxic.

Example: In late monsoon Himalaya, satellite imagery from winter misleads. Seasonal overgrowth can erase side trails and swell creeks. Adding monsoon-season smartphone photos from locals corrected the plan, shifting a camp 2 km upslope to a dry bench.

Poor time and weather window planning

Not all weeks are equal. Seasonality, diurnal cycles, and synoptic patterns decide if your risk is acceptable.

Practical weather planning:

- Choose the right window. Study 10-year reanalysis data for target weeks; note average wind at summit altitude, precipitation frequency, and temperature spreads. For oceanic or polar legs, check sea ice trends and cyclone climatology.

- Forecast with humility. Use at least two models (ECMWF and GFS) and look for convergence. Read ensemble spreads, not just the deterministic run. A narrow spread gives confidence; a wide spread demands larger buffers.

- Diurnal rules. In summer alpine terrain, travel early to beat rockfall and thunderstorms; in polar spring, midday moves may be warmer when diesel and stove efficiency matters; in deserts, pre-dawn for cool temps and lower water consumption.

- Time-control plan. Work backward from hard turnarounds. If summit must be reached by 11:00 to avoid convective storms, schedule wake at 02:30, departure by 03:30, with split times at key features. Pre-commit to turning around if one split is missed by 30 minutes.

Data point: Avalanche risk often spikes 24–48 hours after heavy snowfall when wind slabs form and solar input increases. A plan that pencils in the steepest slopes on day two post-storm is asking for trouble.

Neglecting permits, access, and legalities

Paperwork rarely inspires, but missing it blocks entire expeditions.

Do not skip:

- Access permits and quotas. Popular parks and polar gateways allocate limited slots months ahead. Denali requires registration and a Clean Mountain Can system; some Andean peaks need both municipal and national permissions.

- Research and collection permits. Sampling water, soil, or biological specimens triggers specific approvals. Many countries now enforce export permits for genetic resources under the Nagoya Protocol.

- Visas and carnets. Temporary import documents (ATA Carnet) prevent gear impoundment. If you carry radios, satellites, or drones, learn local licensing regimes. Some regions ban drone flights in protected areas; fines and confiscation are common.

- Insurance fine print. High-altitude rescue, polar medical evacuation, and remote sailing often need specific riders. Many standard policies exclude above 6,000 m or outside national SAR frameworks.

Example: Antarctica tourism is governed by IAATO guidelines. Independent expeditions face strict waste, wildlife, and biosecurity rules. Failing to arrange permits and operator logistics early can make a season impossible; the window is short and ship capacity is capped.

Inadequate team composition and leadership

Strong individuals do not guarantee a strong team. The right blend of skills, roles, and norms matters.

Build deliberately:

- Skills matrix. Map essential competencies: medical care (WFR minimum), crevasse rescue, navigation, mechanical repair, stove maintenance, rope systems, radio operation, and language. Ensure redundancy; never let a single person own a critical skill.

- Role clarity. Assign expedition leader, safety officer, quartermaster, communications lead, and science or documentation leads. Define decision authority and how it changes in emergencies.

- Behavior norms. Codify how you give feedback, challenge decisions, and call for a halt. Encourage speak-up culture; institute a rule that any person can stop the team to reassess without stigma.

Case: A desert crossing team with two superb ultrarunners but no diesel mechanic lost three days to a simple fuel filter issue on a support truck. A basic spares kit and a designated vehicle chief would have turned a showstopper into a 40-minute fix.

Skipping training and rehearsals

The field is the wrong place to test your systems for the first time.

Rehearse like it is real:

- Shakedown trips. Run a two-night mini-expedition with full loads and the actual team. Sleep on the chosen pads, cook on the stoves, use radios with gloves, and navigate at night.

- Emergency drills. Practice crevasse rescue, river crossing with a line, hypothermia wraps, beacon activations, and emergency bivouacs. Time them. Skills you cannot execute cold and hungry are not skills you own.

- Communications checks. Set up your satellite device, test pre-set messages, confirm emergency contacts understand protocols, and verify that your batteries last as long as your power budget claims.

Tip: Film your drills. Short videos become on-expedition refreshers when stress erodes memory.

Overloading or mis-optimizing gear

Weight is a tax on safety, speed, and morale, but false ultralight can be worse. The mistake is not weight itself; it is misallocated weight and poor redundancy.

Better gear logic:

- Weight audit. List every item with grams and function. Highlight mission-critical systems; allow redundancy via PACE (Primary, Alternate, Contingency, Emergency). For navigation, that might be GPS watch, handheld GPS, paper maps and compass, and terrain association skills.

- Standardize power and fuel. Use one battery type if possible; bring a chemistry that tolerates cold (lithium primary cells outperform rechargeables below −10 C). For stoves, plan fuel by environment: white gas excels in cold; canister stoves can fail near −20 C without warming.

- Repair over replace. A compact kit with tenacious tape, needle and dental floss, hose clamps, spare igniter, and ski strap often saves days.

- Fit the environment. Desert dust infiltrates pumps and lenses; bring dust covers and pump rebuild kits. In polar cold, zippers freeze; prefer larger pulls and double sliders. In jungle, prioritize quick-dry fabrics and sand-fly-proof weaves.

Example: A team packed three types of canisters for convenience. In a cold snap, only one model worked reliably. Standardizing would have simplified spares, windscreens, and performance expectations.

Neglecting medical and evacuation planning

A first aid kit is not a plan. You need three pillars: capability, supplies, and a realistic path to care.

- Capability. At least one team member should hold Wilderness First Responder (WFR) or higher; more is better. Practice patient assessments in the environment you will face. Know how to improvise litters and splints.

- Supplies. Customize kits to the mission: blister care and GI meds for treks; anaphylaxis kits where stings are likely; acetazolamide and dexamethasone for high altitude; antibiotics appropriate to regional pathogens (consult travel medicine); hemostatic dressings if using tools with laceration risk.

- Evacuation. Identify extraction points on maps with multiple coordinates (Lat/Long and UTM). Pre-brief the rescue authority; know average response times. Many helicopter rescues are not possible at high altitudes or in storms; your self-evac plan must bridge the gap.

- Documentation and insurance. Carry medical histories, allergies, and consent-to-treat. Verify that your insurance covers remote evacuations and that you understand activation procedures.

Data point: Personal locator beacons transmit on 406 MHz with a 121.5 MHz homing signal; they route through Cospas-Sarsat satellites to national rescue coordination. InReach and similar devices use commercial networks and may route to private centers; plan protocols accordingly.

Underestimating nutrition, hydration, and fuel

Food and water planning seems simple until appetite fades at altitude, snowmelt burns fuel rapidly, and a leaky filter knocks out your water treatment.

Numbers that matter:

- Calorie needs. Cold, load-carrying days can require 4,000–6,000 kcal per person; temperate trekking more like 3,000–4,000. In polar environments, some teams push 6,000–7,000 kcal with high fat ratios.

- Fuel. Melting snow for all water can take 0.15–0.25 L of white gas per person per day, depending on stove efficiency, pot size, and wind management. Add a 20 percent margin.

- Hydration. In arid zones, plan for 0.5–1.0 L per hour of movement. Pre-cache water or use verified sources; do not assume seasonal streams persist through drought years.

Practical tips:

- Menu discipline. Pair dehydrated meals with olive oil or ghee to raise caloric density. Pack a morale food per person; small delights do more for group cohesion than their grams suggest.

- Electrolytes and GI. Carry rehydration salts for diarrhea. Rotate flavors. Avoid only-gel diets beyond a day; they punish stomachs and morale.

- Altitude appetite. Plan energy-dense, easy-to-eat snacks for summit pushes: nut butters, chocolate, cheese, and chews that do not freeze into rocks.

Example day at −10 C pulling a sled: Breakfast 800 kcal (oats, nuts, milk powder), trail 1,500 kcal (cheese, salami, nuts, chocolate), lunch 800 kcal (ramen with added fat), dinner 1,200 kcal (dehydrated meal plus oil), drinks 400 kcal (cocoa). Total around 4,700 kcal.

Failing communications and navigation redundancy

One device is not a plan; it is a single point of failure.

Build a PACE plan:

- Primary. Satellite communicator for routine check-ins and weather; pre-set messages and contacts.

- Alternate. VHF/UHF radios for team comms with spare batteries; rehearse call signs and brevity.

- Contingency. Paper maps and compass for navigation; a route card with bearings and distances.

- Emergency. PLB or EPIRB for life-threatening situations; signal mirrors, flares in marine or polar bear zones.

Details that bite:

- Coordinate systems. Align map datum and coordinate format across devices and printed maps. A mismatch (WGS84 vs NAD27 or UTM zone errors) can place a rescue party hundreds of meters away in zero visibility.

- Power budget. Calculate draw of all electronics and prove it in the field. Solar panels under cloud and low solar angles may underdeliver. Cold sucks life from batteries; insulate and sleep with critical spares.

- Schedules. Implement a daily comms window. Miss two consecutive check-ins and the home base triggers a pre-agreed escalation.

Case: A team using mixed waypoint datums was off by 300 m in forested terrain and burned two hours correcting. A printed legend with the chosen datum and UTM zone taped into each map case would have prevented it.

Budgeting optimism and logistics black holes

Underbudgeting is not just financial; it kills options in the field.

Better budgeting:

- Line-item detail. Include permits, guides, porters, animal hire, fuel, stove parts, batteries, comms subscriptions, insurance riders, medicals, spares, freight, customs, tips, and post-expedition waste disposal.

- Contingency. Add 20–30 percent buffer for unknowns. Remote freight delays, vehicle repairs, and unplanned layover nights happen.

- Freight vs carry-on. Many airlines ban fuel and some stove parts. Plan to source fuel locally, verify availability and purity, and budget time to test it.

- Currency risk. If paying outfitters in local currency, hedge major costs or at least check volatility trends.

Story: A team shipped white gas to a small port only to find local regulations blocked delivery without a hazardous materials broker. The fix cost two days and a 40 percent fee. Better: contract a local outfitter to procure fuel, build the cost into the budget, and confirm with photos.

Disregarding local knowledge and culture

Maps tell you where; people tell you how.

Do not miss:

- Land and community permissions. Private, indigenous, or community-managed lands often require explicit consent beyond state permits. Early relationship-building pays off.

- Cultural rules. Sacred sites, funerary hills, or seasonal migrations shape where you should not camp or fly drones. Violations can end your expedition and harm future access for others.

- Practical intelligence. Guides, porters, and herders know water timing, weather quirks, and river moods. They will tell you which switchback has a wasp nest or where a bridge washed out last month.

Example: On Andean routes, local belief in apus, mountain spirits, can include taboos around summits and offerings. Showing respect by asking about local practices and adjusting behavior builds trust and may unlock safer alternative routes.

Ignoring environmental ethics and impact

Leaving a clean trace is not just virtue; it is logistics and reputation.

Principles into practice:

- Waste systems. Plan human-waste solutions appropriate to the environment: wag-bags or Clean Mountain Cans in alpine zones, catholes only where soils and regulations allow. Manage gray water by straining and dispersing far from streams.

- Fuel vs fire. Stoves trump fires in fragile or high-elevation environments. If fire is allowed, use existing rings and keep it small; do not burn trash.

- Biosecurity. Clean gear to prevent seed spread. On polar or island expeditions, decontaminate footwear and tripods between landings.

- Wildlife. Observe distances and food storage discipline. A single food-habituated animal can force closures that affect many beyond your team.

Lesson: Denali s Clean Climbing policies and mandatory waste carry-out have transformed camp hygiene and reduced crevasse contamination on popular routes. Your plan should match that standard wherever you go.

Overreliance on technology and ignoring human factors

Gadgets dull risk only until the human layer frays. The culprits are predictable: fatigue, dehydration, cold, stress, and cognitive biases.

Countermeasures:

- Checklists and cross-checks. Pre-departure and camp setup checklists catch most errors. Pair up for harness checks, knots, stove shutdowns, and map bearings.

- Sleep discipline. Protect sleep like a critical asset. Chronic sleep deficit degrades decision-making as surely as alcohol. Plan shorter days after poor nights; adjust routes to reduce risk when groggy.

- Bias awareness. Brief the team on summit fever, anchoring, and plan continuation. Invite a designated red team voice to challenge push decisions.

- Hydration and heat-cold balance. Track pee color and frequency; enforce sun protection and warming breaks. Hot drinks are morale and heat in a cup.

Real-world: On a whiteout descent, a team that pre-briefed bias traps turned around at their pre-set time despite a strong gut to press. They later learned a serac had calved across their intended line.

Weak contingency, triggers, and exit strategies

Failure to predefine when to pivot, retreat, or hunker down leads to arguments at the worst moment.

Design your triggers:

- If-Then playbooks. If wind at camp exceeds 70 km/h sustained for 30 minutes, then move to leeward backup camp at Grid 33T 456 789. If two stoves fail, then drop summit bid and descend.

- Objective red lines. Snowpack test results, avalanche bulletins at level 3 or higher on slopes over 35 degrees, or freezing rain forecasts can be automatic no-go criteria.

- Escape routes and caches. Identify at least one exit per leg with known travel times and water. Pre-cache fuel or food where returns may be forced.

- STOP method. Stop. Think. Observe. Plan. Build it into radio comms and pause protocols before terrain cruxes.

Case: A polar party placed a small emergency cache (fuel, food, repair tape, comms battery) halfway between depots. When a sled runner cracked, that cache allowed a controlled retreat rather than a distress call.

Skipping time with numbers: pace, load, and energy

Overoptimistic pace assumptions cascade into poor decisions. Quantify and test:

- Naismith s rule plus corrections. For hiking, budget 1 hour per 5 km on flat plus 1 hour per 600 m ascent. Adjust for load, surface, altitude, and heat. Validate on a shakedown.

- Pack weight ceiling. Keep base weight within a threshold that allows safe movement: many mountaineers aim for under 25–30 percent of body weight for multi-day carries; sled hauling changes the math but still taxes joints.

- Energy burn estimates. Use heart-rate and RPE in rehearsal to link pace to calorie needs. Plan slower days after big efforts to protect recovery.

Example: A team that benchmarked their winter pace with 25 kg loads at −15 C discovered their expected 3 km/h was really 2.1 km/h. They trimmed non-critical gear and added a buffer day; both moves paid off when winds pinned them for 36 hours.

Skipping stakeholder and safety briefings

Expeditions are networks. If support staff, family contacts, outfitters, and rescue agencies are not aligned, your plan can collapse under confusion.

What to brief:

- Route overview with alternatives.

- Comms schedule and escalation plan.

- Medical information and roles.

- Legal documents and permits.

- Logistics timeline for resupplies and transport pickups.

Tip: Send a single-page quick reference to your home base contact with your PACE communications plan, device IDs, expected check-in windows, and explicit do-not-escalate conditions (for missed check-ins due to known dead zones).

After-action learning is an afterthought

Many teams pack up, post photos, and move on. The cost is paid on the next trip.

Bake learning into the plan:

- Structured debrief. Within 72 hours, hold a no-blame meeting. What worked, what failed, what nearly failed, and what surprised you. Gather facts before opinions.

- Capture and share. Maintain a living expedition manual: gear lists with post-expedition comments, route cards with edits, supplier notes, and medical kit changes.

- Update triggers and checklists. Convert each lesson into a checklist item or a concrete trigger condition.

Small habit, big payoff: Keep a nightly log with three bullets per person: one success, one risk noted, one improvement for tomorrow. Those 15 minutes per evening yield more safety than most gadgets.

Putting it all together: a lightweight planning blueprint

To avoid the mistakes above without drowning in paperwork, build a concise expedition plan packet that fits in a single folder on your phone and a small binder in your pack. It should include:

- Mission card

- Primary and secondary objectives

- Success criteria and trade-offs

- Team roles and decision rules

- Route pack

- Overview map with alternatives and escape routes

- Daily route cards with split times, hazards, water, camps

- Coordinate system and datum note

- Risk and safety

- Hazard register with ratings and controls

- Pre-mortem highlights and mitigations

- Medical plan, kit inventory, evacuation routes, insurance details

- Environmental stewardship plan (waste, fires, biosecurity)

- Comms and power

- PACE communications plan and device IDs

- Call signs, frequencies, and licensing info

- Power budget, charging schedule, battery chemistry notes

- Logistics and legal

- Permits, visas, and special licenses (drone, radio)

- Freight plan, fuel sourcing confirmations, spares list

- Budget with 20–30 percent contingency

- Weather and timing

- Seasonal window rationale and historic patterns

- Forecast sources and thresholds for go/no-go

- Time-control plan with turnarounds

- Training and rehearsal

- Drill checklists, timing results, and gaps to close

- Debrief template

- Prompts for post-expedition learning and updates

Print the essentials, laminate the comms page, and keep a pencil in the map case. The aim is not to create a book; it is to carry a pocket system that travels from planning desk to storm-battered tent without losing clarity.

A well-planned expedition feels almost boring when it is working: predictable routines, crisp decisions, and a steady hum of competence. That quiet is not luck; it is the noise you subtracted months earlier by defining success, mapping hazards, training until movements were automatic, and writing down when to turn around. Avoid the common planning mistakes, and you buy yourself the rarest luxury in the wild: room to think clearly when it matters most.

Outdoor Safety Adventure Travel Risk Management Navigation Adventure & Exploration Expedition Planning Risk Assessment route planning team leadership Trip Planning gear checklist permits and regulations weather forecasting communications plan contingency planning medical readiness resupply logistics

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Adventure Travel

Popular Posts