Natural Selection Myths That Most Wildlife Lovers Believe

37 min read Debunk common natural selection myths among wildlife enthusiasts with clear examples, research-backed insights, and practical ways to spot real evolution in the field. (0 Reviews)

Natural Selection Myths That Most Wildlife Lovers Believe

If you spend your weekends glassing a ridgeline for elk or paging through bird field guides, you are already tuned to the rhythms of wild places. Yet even passionate nature lovers carry a backpack full of myths about natural selection. These myths are sticky because they feel intuitive: predators weed out the weak, evolution favors the biggest and strongest, and nature steadily improves herself. The truth is more interesting, more counterintuitive, and far more useful for conservation and responsible wildlife watching. This guide dismantles the most common myths, replaces them with clear concepts, and gives you field-tested ways to think like an evolutionary naturalist.

Myth 1: Natural selection is about the strongest or biggest individuals

Fitness does not mean the heaviest bear or the fastest cheetah. In evolutionary biology, fitness means leaving more viable offspring than the competition. Sometimes strength helps. Often, it does not.

Consider trade-offs:

- Elk antlers: Large antlers can intimidate rivals and attract mates, but they cost enormous energy and calcium. In harsh winters, bulls with massive racks may face higher mortality than moderate-antlered animals because resources are scarce. The winners one year can be the losers the next.

- Soay sheep: Studies on Scottish island Soay sheep show that rams with extremely large horns have high mating success, but they also die younger. Males with modest horn size sometimes leave more total offspring over their lifetimes. A season favoring showy traits can be followed by a winter that punishes them.

- Marine iguanas in El Niño years: When warm currents reduce algae, smaller iguanas, with lower metabolic demands, survive better. The largest individuals, ordinarily competitive, can starve first.

- Island dwarfism and gigantism: On islands, elephants have evolved dwarf forms and rodents have evolved giants. The best-sized body is context specific: on small islands with poor resources and few predators, being smaller can be fitter.

What to look for in the field:

- Watch body condition swing across seasons. A grizzly in spring wears the costs of winter differently than in late summer. The same individual can be alternately fit or stressed depending on context.

- Note behavioral flexibility. A less dominant wolf that is a clever scavenger may rear pups successfully while a brawler is injured in fights.

The takeaway: strongest and biggest are tools in a changing toolbox, not the definition of success.

Myth 2: Evolution has a goal or direction

It is tempting to tell stories of nature improving over time, as if species were climbing a ladder toward sophistication. Evolution by natural selection has no foresight, no finish line, and no universal upward trend.

Examples that break the progress narrative:

- Cavefish lose eyes. In lightless caves, eyes are expensive to grow and maintain. Over generations, eye development genes mutate without penalty, and selection may favor fish that reallocate resources away from eyes toward sensory hairs. The result is a well-adapted fish without sight.

- Parasites simplify. Many parasitic lineages evolve reduced digestive tracts and streamlined bodies. They are not less evolved; they are exquisitely adapted to a host-dependent lifestyle.

- Whales lost legs. The ancestors of whales had four limbs for walking. As they adapted to water, hindlimbs regressed. Losing structures can be adaptive.

- Parallel solutions repeat. Anoles on different Caribbean islands evolved similar ecomorphs (long-legged trunk runners, twig specialists) independently, showing that evolution often explores the same peaks given similar environments, not because it seeks higher forms but because certain combinations work.

Practical mindset shifts:

- Replace why with how. Instead of asking why nature wanted a trait, ask how a trait helps an organism solve a local problem.

- Expect reversals. Traits can be gained and lost as environments flip. The Red Queen principle applies: organisms must keep evolving simply to keep up with changing competitors, predators, and climates.

Myth 3: Individuals evolve during their lifetimes

A common confusion is between acclimation and adaptation. Acclimation is a short-term, reversible adjustment within an individual. Adaptation is a genetic shift across generations.

Contrast the two:

- High altitude humans: You can acclimate to thin air by increasing red blood cell count. But populations like Tibetans show genetic adaptations in oxygen processing (one gene, EPAS1, has been implicated) that reduce the harmful costs of making excess red blood cells. That is adaptation.

- Summer heat: A desert lizard can adjust heat-shock protein levels daily. That is acclimation. But desert populations may evolve genetic changes in skin pigmentation and metabolism over many generations.

- Predator-induced helmets in Daphnia: Water fleas raised in the presence of chemical cues from predators grow protective helmets. The trait is plastic: it turns on when needed. But the capacity to deploy that plasticity is encoded in genes and shaped by selection.

Actionable tip for observers:

- Track timescales. If a trait appears and disappears within days or weeks for the same individual, you are seeing plasticity. If a trait is stable across generations and geographic regions, you are seeing evolution. Carry a field notebook, and note both timescale and inheritance clues.

Myth 4: Every trait is an adaptation

Selection is not the only evolutionary force. Random genetic drift, hitchhiking with nearby genes, and developmental constraints can shape traits without direct adaptive value.

Illustrations:

- Elephant seal bottlenecks: Northern elephant seals were hunted to a handful of individuals in the 19th century and then rebounded. Their genetic diversity is low because of a bottleneck. Many neutral genetic variants were lost or fixed by chance, not because they were adaptive.

- Hitchhiking genes: A beneficial mutation can drag along nearby alleles simply because they are physically close on a chromosome. The hitchhikers spread even if they do nothing by themselves.

- Spandrels analogy: Some traits are by-products of building an organism. A classic example is the human chin, which may be a structural by-product of facial architecture rather than a trait with a specific adaptive story.

- Zebra stripes: Competing hypotheses propose roles in thermoregulation, biting fly avoidance, or social recognition. Different species of zebra have different stripe patterns. Be cautious with tidy one-sentence explanations; the full story may involve multiple weak effects plus historical constraints.

Field practice:

- Use the null hypothesis. If you cannot test an adaptive story, consider whether drift or constraint could explain the pattern.

- Compare populations. If a trait varies wildly without consistent environmental correlation, it might be neutral variation.

Myth 5: Natural selection always favors healthier populations and species

Selection tends to operate at the level of genes and individuals, not entire species. What is favored for an individual can harm the population.

Real-world tensions:

- Sexual conflict: Males of some species evolve traits that boost their mating success but harm female longevity or fertility. In many water striders, males develop strategies that increase their own mating opportunities while stressing females.

- Trophy traits: Extremely large antlers or horns can be favored by sexual selection, even if they reduce survival. Combine that with human trophy hunting of the largest males, and you rapidly shift trait distributions in a direction that is not population-healthy.

- Overexploitation strategies: Individuals that grab a resource early gain in the short term even if the local habitat degrades. Think of nesting sites where early breeders usurp prime spots.

- Cancer inside bodies: Within a single organism, cell lineages that proliferate faster can outcompete their neighbors even if the cancer kills the host. Nature contains selection at multiple levels, and it does not always aggregate to the good of the whole.

Conservation takeaway:

- Do not expect selection to rescue a population from self-inflicted traits. Managers sometimes need to counteract harmful selection, for example by adjusting harvest rules or protecting large, late-maturing individuals to maintain life-history diversity.

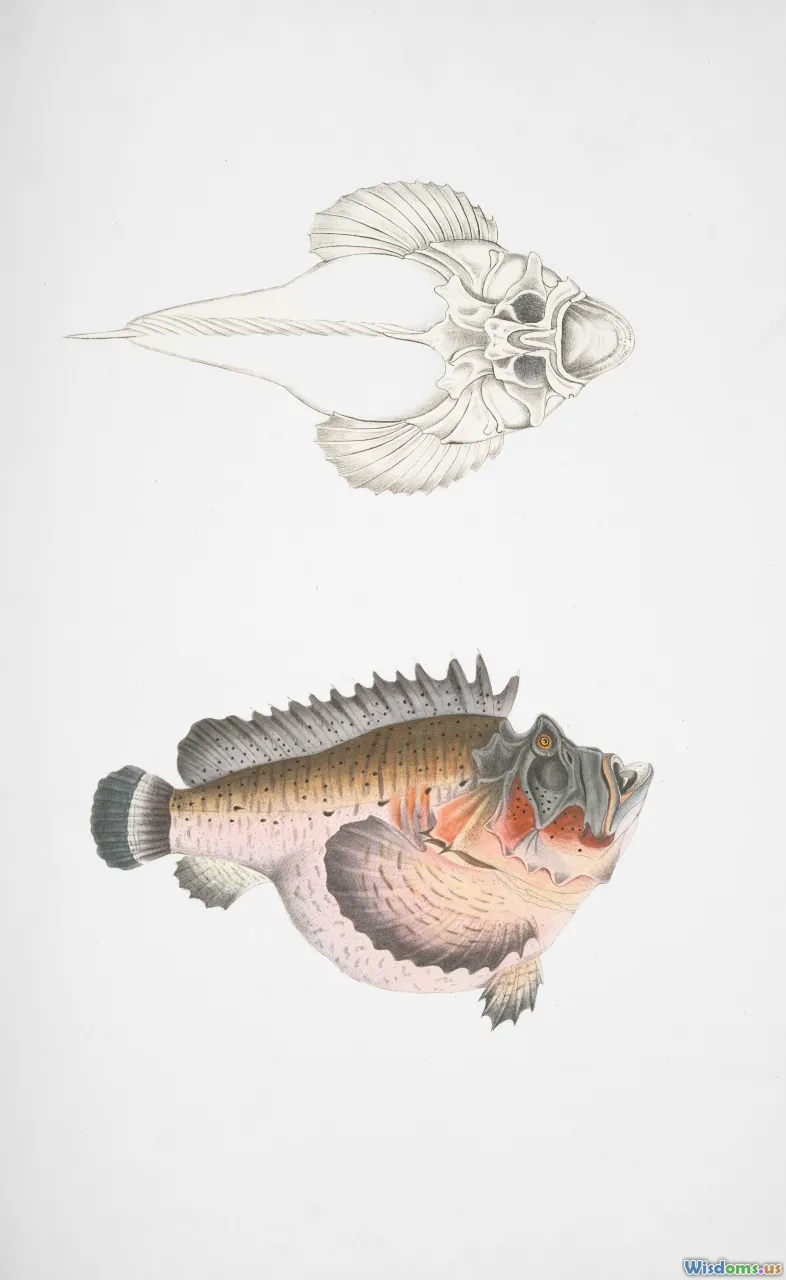

Myth 6: Predators only target weak, sick, or old prey

Predators do often take vulnerable prey, especially when the cost of hunting is high. But they also exploit predictability, habitat edges, and weather. Many kills are of animals in their physical prime.

Examples from the field:

- Wolves and elk: In deep snow, prime-age elk cows can be overrepresented in wolf kills because they are energetically valuable and temporarily handicapped. Wolves do not assess an elk's medical record; they test for vulnerability in the moment.

- Lions and zebra: Lions frequently attack zebras at watering holes where escape routes are limited. These zebras may be healthy but are forced into predictable, risky space.

- Cougars and deer: Cougars often key on the most abundant prey class, which can be the healthy subadults. Ambush predators profit from surprise, not just infirmity.

What to observe:

- Terrain and timing. Watch when and where hunts succeed. Snow, mud, and dense cover can equalize prey condition differences.

- Group behavior. Predation shapes herd sizes and vigilance, not just individual survival. A tightly bunched herd reduces per-capita risk but may drive less dominant members to the edge where they become targets.

Evolutionary insight:

- Predation can maintain diversity by preventing the most competitive species from monopolizing resources, a process called keystone predation. This selection regime influences behavior and life history strategies broadly, not merely a culling of the obviously weak.

Myth 7: Natural selection quickly solves conservation problems

Sometimes evolution is fast. Often it is not fast enough to match human-caused change.

Rate mismatches:

- Climate pace: Alpine pikas rely on cool microclimates. As summers warm and snowpacks shrink, the climatic window moves uphill faster than pikas can disperse or adapt genetically. Behavior can buffer for a while, but there are limits.

- Coral bleaching: Some corals host heat-tolerant symbionts and can shuffle symbiont species to increase resilience. Yet the frequency and intensity of marine heatwaves can outstrip these adjustments, leading to mass bleaching.

- Migration cues: Birds that time migration by day length may mismatch peak insect abundance as spring advances earlier. Some species adjust lay dates; others cannot.

Yet, rapid evolution is real in some cases:

- Urban anoles: Lizards in cities have evolved larger toe pads and limb proportions that improve grip on smooth, hot surfaces within a few dozen generations.

- Soapberry bugs: In regions where invasive plants replace native hosts, beak length in these insects has evolved quickly to exploit new fruit sizes.

- Great tits: In some European woodlands, lay date has advanced measurably, aligning better with earlier springs.

Action steps for conservation-minded observers:

- Support habitat heterogeneity. Microrefugia (north-facing slopes, deep pools, shaded ravines) buy time for both acclimation and adaptation.

- Think generation time. Species with short generation times (insects, annual plants) can adapt quickly; long-lived mammals often cannot keep pace. Prioritize reducing rapid stressors for the latter.

Myth 8: Domestication and captive breeding are the same as natural selection

Artificial selection is targeted, often narrow, and guided by human goals. Natural selection is diffuse, context-dependent, and unforgiving.

Key differences with examples:

- Hatchery salmon: Fish bred in hatcheries may be selected inadvertently for traits that thrive in concrete raceways, such as tolerance for crowding or altered foraging. When released, many do poorly in the wild, and their genes can reduce fitness of wild-born offspring.

- Belyaev foxes: The famous fox domestication experiment selected for tameness. Within a few dozen generations, foxes developed floppy ears and piebald coats, a suite of changes known as domestication syndrome. Useful in captivity; liabilities in the wild.

- Anti-poaching and horn size: Selective trophy hunting has led to observed declines in horn size in some bighorn sheep populations. That is selection, but not natural selection, and it pushes traits in directions that may not maximize survival in the wild.

Practical guidelines:

- Separate breeding goals. If the objective is reintroduction, emulate natural selection pressures in captivity: variable environments, predator cues, and foraging challenges.

- Minimize domestication selection. Keep generations in captivity as few as possible before release. Rotate broodstock. Use semi-wild enclosures where feasible.

Myth 9: Hybridization is always bad

Hybridization can threaten rare species through genetic swamping, but it also fuels adaptation and can produce successful lineages.

Nuanced realities:

- Eastern coyotes: Many eastern coyotes carry wolf and dog ancestry. The resulting mix appears to confer larger body size and flexible diet, helping them exploit suburban landscapes. They are not failed coyotes; they are a new coyote flavor tuned to modern America.

- Darwin's finches: Finches on the Galápagos occasionally interbreed, moving genes across species boundaries. This gene flow can introduce useful traits, like beak shapes that match fluctuating seed types.

- Pizzly bears: Polar-grizzly hybrids have been documented where ranges overlap. The ecological future of such hybrids is uncertain, but the event itself is not unnatural.

Risks and management:

- Outbreeding depression: Mixing very divergent lineages can break co-adapted gene complexes, reducing fitness in harsh environments.

- Conservation choices: For rare canids like red wolves, managers weigh the genetic integrity of a historical type against the adaptability afforded by hybrid genes. There is no one-size answer; the right choice depends on legal definitions, ecological roles, and risk tolerance.

Field tip:

- Document morphology and behavior without pre-labeling hybrids as failures. Take high-quality photos of pelage, size, and behavior, and note location and habitat. These records inform science without bias.

Myth 10: Cooperation and altruism refute natural selection

On the surface, helping others at a cost to oneself seems anti-Darwinian. But cooperation evolves via several well-understood mechanisms.

Mechanisms with examples:

- Kin selection: Genes that promote helping relatives can spread because relatives share genes. Meerkats take turns as sentinels; though a sentinel risks being seen, the group benefits, and sentinel duties are often biased toward kin.

- Reciprocal altruism: Help now, get help later. Vampire bats regurgitate blood to feed unrelated bats that failed to feed; the favor is tracked and returned.

- Mutualism: Different species cooperate when both benefit. Cleaner fish remove parasites from large reef fish; cleaners gain food, clients gain health. Cheaters exist, but partner switching and reputations stabilize the system.

- Byproduct benefits: Migration flocks form not because each bird wants to help others, but because riding updrafts in V formation saves energy for all. Cooperation emerges from selfish rules.

How to analyze cooperative behavior in the field:

- Map relatedness: Are helpers siblings? Do dominant individuals tolerate helpers more when they are kin?

- Track reciprocity: Do grooming or food-sharing interactions return to the helper later?

- Look for partner choice: Do animals abandon cheaters, or do clients prefer reliable cleaners?

Myth 11: Natural selection only acts on genes

Genes are the substrate, but selection also acts on how organisms modify their environments and pass on non-genetic information.

Layers beyond DNA:

- Epigenetics: Environmental conditions can alter how genes are expressed via chemical marks. Some of these marks persist across generations temporarily. While not a substitute for genetic change, epigenetic mechanisms can buffer populations while genetic adaptation catches up.

- Culture: Elephants learn migration routes from elders. Orca pods have distinct hunting cultures (seal-hunting vs fish specialists), and these cultures influence survival and reproduction.

- Niche construction: Beavers build dams, changing hydrology, plant communities, and predator dynamics. These modifications feedback on beaver selection by altering resource abundance and predation risk.

- Gene-culture coevolution: Human lactase persistence evolved in populations with dairy culture. In wildlife, think about birds that have learned to exploit human-provided feeders; persistent culture can bias selection toward traits that exploit new niches.

Practical implications:

- Protect teachers: In species where older individuals transmit critical knowledge, removing matriarchs or elders can depress population fitness beyond what simple numbers predict.

- Conserve structures: Beaver dams, termite mounds, and prairie dog towns are not passive backdrops; they are adaptive innovations that merit protection as keystone features.

Myth 12: Selection stops in stable environments

Even apparently steady environments are dynamic at biological scales. Selection is constant because competitors, parasites, and prey evolve.

Classic dynamics:

- Red Queen hypothesis: Species must keep evolving to maintain relative fitness as others change. Host-pathogen arms races are a prime example; MHC immune genes remain diverse because pathogens adapt to common host genotypes.

- Frequency-dependent selection: The fitness of a trait depends on how common it is. Scale-eating cichlids with left- or right-curved jaws alternate in abundance; when left-biters are common, prey watch their left flank more, giving right-biters an edge, and vice versa.

- Seasonal pulses: In temperate lakes, plankton face different predator regimes across spring, summer, and fall. Life cycles and reproduction timing adjust constantly.

Field applications:

- Expect cycles: If you monitor a population for years, look for oscillations in trait frequencies, not monotonic trends.

- Use multi-year baselines: Single-season snapshots mislead. Pair your photographs and notes with weather and phenology records.

Myth 13: Dominance equals fitness and the alpha always wins

Pop culture casts nature as a ladder with an alpha at the top. Real dominance structures are more complex, and dominance does not guarantee genetic success.

Nuance across species:

- Wolves: Wild wolf packs are family units, typically led by a breeding pair. The so-called alpha concept from captive wolves has misled the public. Subordinate wolves often help raise pups to which they are related. Dominance displays exist, but long-term reproductive success depends on cooperation, territory quality, and pup survival.

- Baboons: High-ranking males may win access to estrous females, yet males who form friendships with females and their infants sometimes secure more paternities over time. Social strategy competes with brute force.

- Birds with helpers: In cooperative breeders like Florida scrub-jays, non-breeding helpers enhance the success of relatives. A dominant bird monopolizing food may decrease group productivity and, ultimately, its own long-term fitness if helpers disperse or die.

Practical observation tips:

- Track offspring, not just fights. If you photograph a dominant bull elk, follow through to see how many calves survive in following seasons.

- Note alliances. Coalitions and friendships often shift breeding outcomes in primates and dolphins.

Myth 14: Conservation should favor the fittest individuals

Selecting only the strongest-looking animals for protection or breeding sounds sensible but can backfire. Conservation seeks resilience, not just short-term vigor.

Key principles:

- Genetic diversity is a hedge. Populations with higher heterozygosity can withstand new diseases and climate shifts. Removing the runts can reduce genetic variation.

- Inbreeding depression is real. Small isolated populations often accumulate harmful recessive alleles. Florida panthers suffered heart defects and low sperm quality; a managed introduction of Texas cougars increased genetic diversity and improved health.

- Purging is risky. The idea that populations purge bad alleles by letting weak individuals die only works under some conditions and can drive small populations to extinction before any purging benefits arrive.

Management guidance:

- Protect variation across space. Maintain corridors that allow gene flow. Edge populations often carry unique adaptations.

- Balance selection pressures. If harvests target the largest fish, size at maturity can evolve downward. Adjust regulations to protect a portion of big, old spawners to maintain life-history diversity.

Myth 15: Natural selection eliminates all mistakes and inefficiencies

Nature is full of kludges, workarounds shaped by history. Selection works with what is available, not what an engineer would design from scratch.

Evolved compromises:

- Panda thumb: Giant pandas use a modified wrist bone as a pseudo-thumb for grasping bamboo. It works, but it is a hack, not a designer thumb.

- Giraffe nerve detour: The recurrent laryngeal nerve takes a circuitous route from brain to larynx, looping under the aorta. Historical anatomy constrains routes; selection can only adjust around existing structures.

- Bird respiratory system: Highly efficient flow-through lungs evolved within the constraints of avian anatomy. It is a marvel, but even marvels carry trade-offs like susceptibility to aerosolized toxins.

Field lesson:

- When you see something that looks suboptimal, ask what compromise it represents. Often a trait balances competing demands: speed vs maneuverability, fecundity vs parental care, armor vs mobility.

Myth 16: If a species is present, it must be perfectly adapted to its habitat

Presence does not imply perfection. Many populations persist in sink habitats where reproduction does not keep up with mortality, maintained by immigrants from better habitats.

Reality checks:

- Metapopulations: Butterflies and amphibians often occupy patchy habitats where local extinctions and recolonizations are common. A pond can hold frogs this year only because nearby ponds continuously export tadpoles.

- Ecological traps: Human-altered environments can lure animals into poor choices, like birds nesting in fields that are mowed before chicks fledge. Adaptations tuned to historical cues misfire in novel landscapes.

What wildlife lovers can do:

- Map sources and sinks. If you volunteer for monitoring, help identify which patches export animals and which are sinks. Protect sources; mitigate traps.

- Reduce traps. Delay mowing, shield reflective glass, use downward-directed lighting, and avoid rodenticides that poison scavengers.

How to think like an evolutionary naturalist in the field

Use these habits to replace myths with insight every time you step outside:

- Start with variation. Before searching for explanations, look for differences: size, color, timing, behavior. Take photographs with scale references and time stamps.

- Ask what problem a trait solves here and now. A sandpiper's bill length only makes sense in relation to local prey depth and substrate.

- Think in trade-offs. If you spot a heavily armored beetle, consider what it pays in speed or reproduction.

- Consider timescale and inheritance. Separate plasticity from adaptation by asking whether the trait appears quickly in individuals or persists across generations.

- Use comparisons. Check multiple sites or related species. If a trait changes with environment, selection is a good suspect. If not, drift or constraint may be at work.

- Avoid teleology. Do not assign purpose; describe function. Say this shape deflects water rather than it was designed to.

- Keep a skeptical notebook. Jot hypotheses, then note observations that could prove them wrong. Science advances by eliminating bad ideas.

Practical mini-projects for wildlife lovers:

- Seasonal beak diaries: Photograph the same finch flock monthly. Note changes in bill wear and seed types. Ask if diet switches are plastic or tied to influx of migrants with different bills.

- Predator pathway mapping: Trace trails where coyotes or foxes travel. Record habitat features where you find scat and tracks. Over time, test whether ambush sites correlate with certain vegetation structures.

- Microrefugia hunt: In a local park, log the coolest spots in summer and warmest in winter. Observe which species cluster there. Consider how these spots might aid adaptation by sheltering sensitive individuals.

Spotting myths in documentaries and social media

Nature stories deserve good science. Here is how to enjoy the cinematography without swallowing myths:

- Red flags in narration: Beware phrases like nature designed, to make the species stronger, or the alpha. Substitute neutral language in your head: selection favored, individuals with trait X left more offspring, the breeding pair.

- Check for single-cause stories. A dramatic sequence might say stripes evolved to dazzle predators. Ask what alternate explanations exist and whether evidence supports multiple effects.

- Beware of tidy arcs. Evolutionary change is messy, with dead ends and reversals. If a film tells a linear progress story, treat it as artful framing, not a literal account.

- Use official bonus materials. Many documentaries publish behind-the-scenes details. Directors often admit when a narration simplified the science. Seek out those notes.

Applying evolutionary thinking to backyard choices

Your yard and neighborhood are microcosms where selection plays out. Small choices add up:

- Plant natives in layers. Diverse plant structure supports diverse insect prey, which supports birds with different foraging strategies. Variation creates options for selection to act on.

- Time your feeder use. If you feed birds, do so strategically: clean feeders to reduce disease selection for tolerant strains, pause feeding during outbreaks, and avoid creating crowding hotspots.

- Support predators indirectly. Brush piles and deadwood host small mammals and insects. Raptors and foxes follow. Balanced food webs create varied selection pressures that maintain resilient communities.

- Light discipline. Night lighting disrupts navigation and selects for traits that tolerate light pollution. Use warm, downward-directed lights and motion sensors.

Choosing stories that do justice to nature

When you lead a hike, post a photo, or talk to kids, choose language that reflects the complexity you now appreciate:

- Trade the hero tale for a web of interactions. Replace biggest wins with resourceful strategies across seasons.

- Emphasize change. Describe how this valley rewards different traits after fire, drought, or heavy snow.

- Celebrate diversity. Point out the oddballs: the small moose that winters well, the crow that innovates new foraging tricks, the wildflower that blooms off-schedule and still sets seed.

Natural selection is not a gladiator arena with one victor. It is a patient, improvising force that assembles workable solutions from imperfect parts, in places that shift underfoot. When you leave the myths behind, every track, feather, and leaf scar becomes a clue. And your choices, from what you plant to how you tell stories, can make your corner of the world a better laboratory where wildlife keeps finding new ways to live.

Wildlife Conservation Biology Natural Selection evolution Wildlife Behavior genetic variation Adaptation Science Communication Wildlife & Biology Genetics & Evolution sexual selection evolution myths survival of the fittest selection pressure evolutionary trade-offs fitness vs strength misconceptions

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Genetics & Evolution

Popular Posts