Space Mining and the Future Economy: Risks and Rewards Explained

19 min read Explore the risks and rewards of space mining and its impacts on the global economy. (0 Reviews)

Space Mining and the Future Economy: Risks and Rewards Explained

A century ago, extracting resources from the Moon or distant asteroids sounded like pure science fiction. Today, driven by spectacular advances in rocketry, robotics, and artificial intelligence, space mining is on the verge of moving from concept to reality. But what does this epochal leap mean for nations, industries, investors, and humanity’s collective future? The rise of space mining opens doors to immense rewards — and warns us of daunting risks. This article explores the landscape, technology, players, and critical economic questions shaping the future of mining beyond Earth.

Space Mining: An Idea Whose Time Has Come

It was not so long ago that the resources locked within asteroids or on the Moon were the stuff of speculative fiction. But consider these figures: NASA estimates that a single metallic asteroid a kilometer wide could hold more nickel, iron, cobalt, and platinum group metals than mined in all of human history. The value of such resources is almost incalculably large — the asteroid 16 Psyche, for example, has been valued anywhere from $10 quadrillion to $700 quintillion, owing to its nickel-iron core. While these vast numbers are theoretical, they illustrate an awe-inspiring potential.

More importantly, several factors are quickly converging:

- Declining Rocket Launch Costs: Thanks to reusable launch vehicles by companies like SpaceX, the cost per kilogram to orbit has plummeted from tens of thousands of dollars to as low as $1,000–$3,000, and continues to fall.

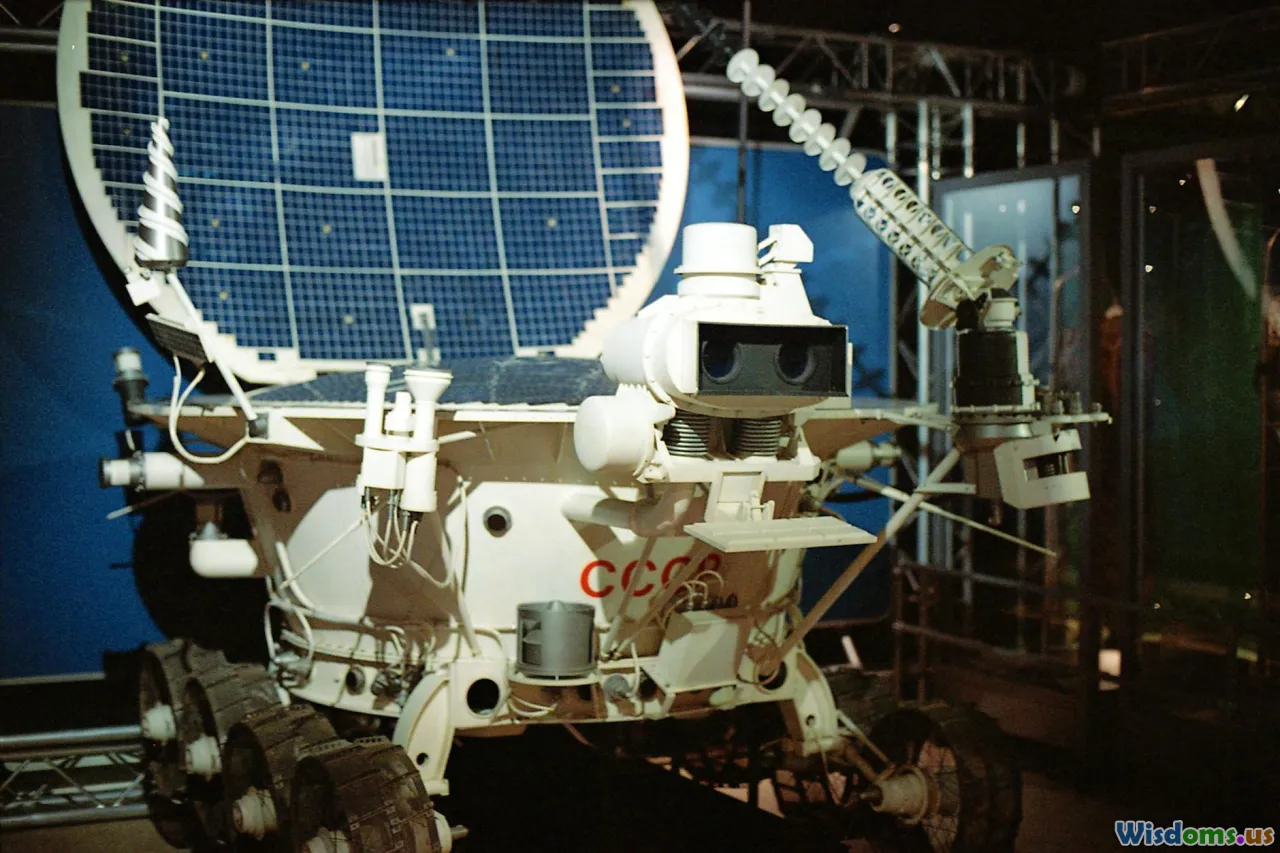

- Autonomous Robotic Technology: Robotic probes, such as Japan's Hayabusa2 and NASA's OSIRIS-REx, have successfully mapped, landed on, and sampled asteroids, proving technical feasibility.

- Interest from Governments and Private Industry: The United States, Luxembourg, and the United Arab Emirates have passed legal frameworks to promote off-Earth mining. Companies such as Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries (now part of Bradford Space) pionereed early technological efforts.

While human civilization faces hard constraints on resource extraction on Earth, space mining opens the door to potentially limitless expansion — and new questions about the structure of the global economy.

What Makes Space Mining Attractive?

There are three central economic drivers making space mining an irresistibly attractive prospect:

1. Surplus of Precious and Rare Elements

Many of the crucial technologies guiding our present and future, including smartphones, wind turbines, electric vehicles, and green energy systems, rely heavily on rare metals: platinum, cobalt, palladium, and various rare earth elements. On Earth, these are highly concentrated in a handful of geographies, leading to supply bottlenecks and price volatility.

Asteroids, relics from the solar system's formation, frequently contain much higher percentages of these elements than even Earth’s richest ore mines. For example, the platinum output from just one medium-size asteroid could outstrip humanity’s annual consumption for decades. Thus, successful asteroid mining could:

- Flood markets, radically changing commodity prices

- Ease geopolitical tensions over scarce resources

- Enable advancements in electronics and clean energy technologies

2. Building Off-World Infrastructure

Mining not only offers exportable resources. Extracted metals, water, and oxygen could be used immediately to build and sustain habitations, fuel, and manufacturing off-Earth. Water ice, for instance, can be converted into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel, turning remote mining sites into depot hubs for solar system travel.

3. Addressing Earth’s Limits

Even as recycling tech improves, the Earth’s resources — particularly for rare elements — are finite. Economically and ecologically, the burden of ever-deeper, more hazardous mining grows heavier. Off-Earth mining could reduce terrestrial destruction and offer a blueprint for wiser stewardship of our home planet.

How Does Space Mining Work in Practice?

The core principles of mining in space borrow from terrestrial mining, but the execution differs through unique constraints and opportunities. Here's how the process typically unfolds:

1. Prospecting and Site Selection

Robotic probes scan asteroids or the Moon for promising ore bodies, using instruments like spectrometers, radar, and X-ray imagers. NASA's NEAR Shoemaker mission demonstrated this with Eros, while Roscosmos (Russia's space agency) and ESA have developed similar instruments for lunar resource mapping.

2. Landing and Anchoring

Unlike on Earth, most asteroids have weak or no gravity. This means miners must either harpoon, anchor, or envelop an asteroid to prevent the equipment from rebounding into space. In 2019, Japan's Hayabusa2 fired a projectile at asteroid Ryugu and briefly touched its surface to gather precious grains — a first for any probe.

3. Excavation and Extraction

Techniques vary based on the target. For stony or metallic asteroids, drills and grinders shred regolith and expose ore. For carbonaceous asteroids, heating may vaporize water, which is then captured as it off-gasses. The extraction process must be highly automated, adaptable to various gravities, temperature extremes, and unpredictable surface properties.

4. Processing and Transport

The next challenge is to process the minerals, potentially refining metals or creating water fuel propellant on site, to minimize return mass to Earth. Robotic systems and small chemical plants are in development to manage this under microgravity conditions.

Example: NASA's planned Lunar Gateway envisions in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) for supporting lunar exploration using locally sourced oxygen, water, and metals.

Leading Players and Projects: Who is Chasing Space Riches?

The race to tap off-Earth resources involves a blend of nations and enterprising new companies, each with its approaches.

National Space Agencies

- NASA (USA): With the Artemis missions and Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, the US is funding a suite of lunar resource prospecting technologies.

- ESA (EU): The European Space Agency plans a lunar mining demonstration within this decade in collaboration with private contractors.

- CNSA (China): China’s Chang’e program aims at lunar sample return, with long-term ambitions for exploiting lunar Helium-3, a rare potential fusion fuel.

- JAXA (Japan): Built on Hayabusa and Hayabusa2 missions, JAXA has established expertise in asteroid rendezvous and sample return.

Private Companies

- Bradford Space: After acquiring Deep Space Industries, focuses on advanced in-space propulsion and mission systems for asteroid mining.

- iSpace (Japan): Spearheading lunar lander technology and aiming at resource prospecting missions.

- Planetary Resources (defunct): Once raised $50 million at its peak, illustrating massive early investor interest.

- Moon Express, Astrobotic: Compete to provide lunar transport and prospecting services for clients ranging from NASA to private investors.

Corporate and national ambitions are interwoven. NASA actively contracts private companies to develop lunar mining robots, and Luxembourg invests state funds into venture capital for space mining startups, aspiring to be the regulatory heart of space resources.

Economic Rewards: Boon or Bubble?

The projected benefits of space mining sparkle, but do they stand up to scrutiny? Let’s break down the most critical economic impacts and potential rewards.

Flooding the Market — or Building It?

Proponents envision a cascade of new supply changing the world’s resource map:

- An End to Scarcity: If a large platinum-rich asteroid’s metals flood global markets, prices for these once-exotic elements could collapse, enabling mass production of high-tech goods.

- Post-Scarcity Economy: Some dream of a future where resource limits virtually disappear, supporting higher standards of living and technology.

But here’s the economic twist: if metals pour onto global markets, prices likely plummet, undercutting the profitability of further extraction. Many analysts predict that a controlled "drip feed" of asteroid materials, rather than a flood, would optimize economic outcomes.

Critical Role in In-Space Economy

Some experts argue the real value lies not in shipping metals home, but in local use:

- Space Construction: 3D printing and manufacturing infrastructure in orbit, on the Moon, or Mars becomes future feasible if raw materials are readily available in situ — far cheaper than launching heavy payloads from Earth.

- Refueling Stations: Water ice mined from asteroids or lunar poles converts into rocket propellant, forming the basis of a refueling supply chain and slashing interplanetary travel costs.

Technological Spinoffs

As with the space race of the 1960s, the money spent on these high-risk ventures will inevitably spur new materials, autonomous AI, remote robotics, and energy-processing innovations, which could reverberate across terrestrial industries for decades.

The Risks and Challenges: Pandora’s Box?

Despite the promise, the risks spanning technology, finance, politics, and the environment are colossal.

1. Legal Gray Areas

Who really owns the Moon or an asteroid? Nations largely follow the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits any nation claiming sovereignty, yet the treaty is ambiguous on private commercial activity. The U.S., United Arab Emirates, and Luxembourg recognize commercial claims to extracted space resources, while Russia and China see this as potential neocolonialism.

As off-Earth mining inches closer, the lack of unified legal frameworks could cause international disputes or even conflict. Who arbitrates if multiple miners land on the same asteroid, or if a debris collision occurs during mining?

2. Economic Wild Cards

What if space mining leads to wild commodity price crashes or localized terrestrial unemployment as traditional mines shutter? Asteroid mining might create brutal "boom-bust" cycles unlike anything on Earth, challenging economists and policymakers.

Additionally, the funding risk is severe: Every mining venture may cost hundreds of millions in initial investment, with years—often decades—until any prospect of return.

3. Technological Uncertainties

Extracting rocks in microgravity, operating without real-time human control, and managing dust, electrostatic discharge, or unpredictable surface composition will challenge engineers. The history of Mars rovers and lunar missions is testament to how complex robotic operation remains in hostile environments.

A recent cautionary tale: In 2019, the Israeli Beresheet lunar lander crashed during descent, a reminder of how high the technical bar remains even for unmanned operations.

4. Environmental and Ethical Concerns

Could we transfer ecological destruction into orbit? Debris from mining, or redirected asteroids, pose risks of catastrophic impacts on satellites or even Earth's surface.

Moreover, questions arise about access and benefit. Will a handful of mega-corporations or wealthy nations dominate the extraction and profits, or will international frameworks ensure shared benefit and opportunity?

How to Navigate the Risks: A Roadmap for Responsible Development

Given these perils, how should humanity proceed? Here are actionable strategies for investors, entrepreneurs, policymakers, and citizens:

1. Build Robust International Legal Frameworks

Global governance structures — perhaps modeled on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea — should be forged now, not later. The aim: clear property, liability, and environmental obligation rules for mining enterprises. International observatories or "space mining authorities" can arbitrate disputes and ensure activity respects agreed-upon norms.

2. Prioritize Sustainable Engineering

"Minimize debris" protocols, rigorous mission planning, and strict liability coverage (e.g., insurance mandates) can mitigate much of the environmental hazard of unintended impacts and debris generation.

R&D investments should be directed towards flexible, redundant robotic systems that can operate under a variety of unexpected conditions, learning from the failures and successes of recent space missions.

3. Foster Open Data and Global Benefit Sharing

Open access to prospecting data (via incentives or regulations) could discourage monopolization. International consortia and joint ventures — such as Artemis Accords partners — ensure a wider range of beneficiaries and skillsets.

A royalty or resource-sharing fee structure, similar to terrestrial oil and gas models, could help fund global science or sustainability efforts, linking profits to planetary stewardship.

4. Start Small and Iterate

Just as commercial aviation grew from mail flights to global passenger transport, the first profitable space mining enterprises may begin with niche markets: water supply for satellites, rare isotopes for specific industries, or even lunar regolith for 3D printing limited structures. Gradual scaling, with solid engineering and business models, can prevent boom-bust bubbles and magnify learning.

Could Space Mining Change Your Life?

You may never don a spacesuit or chip platinum from a moving asteroid, but the consequences of successful space mining could ripple across your daily life in the future:

- Cheaper Technology: If platinum and rare earth shortages are eased, electric vehicles, quantum computers, and clean energy could become vastly more affordable and widespread.

- Greener Earth: Off-Earth resource harvest could offset some of the environmental destruction and pollution associated with mining (if managed responsibly).

- Space Careers: New fields — from orbital construction to remote mining operations management — will emerge as growth sectors.

- Global Challenges and Policy: Debates on resource sharing, wealth inequality, and technological ethics will shape politics, business, and education.

As Jeff Bezos famously proclaimed, “We need to go to space to save the Earth.” With commitment and caution, space mining may indeed let us reach boldly outward and sustain our home for generations to come.

Space mining is not just a sci-fi fantasy, but a budding reality brimming with both promise and peril. The next ten years will determine whether it becomes an engine for global prosperity — or a cautionary tale in cosmic overreach. The world is watching. Will we wield this power wisely?

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts