The Art of Camera Movements in Modern Filmmaking

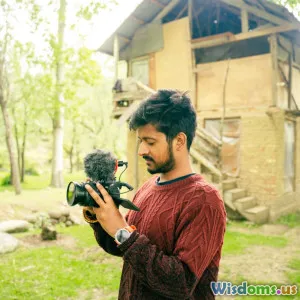

35 min read A strategic guide to camera movements that enhance storytelling, emotion, and pacing in modern filmmaking, with practical examples, techniques, gear choices, and tips for intentional, motivated motion. (0 Reviews)

A camera that stays still can make a scene feel like a painting; a camera that moves turns it into a sentence with verbs. In modern filmmaking, movements are the punctuation and cadence of visual storytelling—emphasis, whispers, interruptions, crescendos. The same story beat, played with a locked-off frame versus a slow push-in, lands differently. This is the art of camera movement: choosing how, why, and when to move so the audience feels the story rather than merely observing it.

What Camera Movement Really Does to Story and Audience

If you strip away gear and jargon, camera movement is about emotion, psychology, and audience attention.

- Emotional guidance: A slow push-in tells us to lean in—it quietly concentrates emotion. A retreating pull-out can increase distance, emphasizing isolation. A lateral tracking shot can create restlessness, like pacing.

- Point of view and empathy: A dolly move that closes the gap between character and camera often signals alignment with their inner state; a circling move around two characters can suggest connection, tension, or confusion depending on speed and direction.

- Spatial comprehension: Moving the camera through space clarifies geography, reveals relationships among objects and characters, and creates parallax (the relative shift of foreground and background) that communicates depth.

- Rhythm and tension: Movement tempo primes expectation. Acceleration builds tension; deceleration lets moments breathe. Even the shape of the motion curve matters: linear speed feels mechanical; eased-in/eased-out acceleration feels organic.

Modern viewers are sensitive to these cues. The average shot length in mainstream films often hovers around 3–5 seconds, but when films choose longer takes with measured camera movement—think 1917 or the Goodfellas Copacabana sequence—audiences intuitively feel continuity, immersion, and stakes. The craft is not in moving more, but in moving with intent.

A Field Guide to Modern Moves

Here’s a practical overview of core moves, the feelings they evoke, and where they shine.

Pan and Tilt

- What it is: Rotating the camera left/right (pan) or up/down (tilt) from a fixed point.

- When to use: To reveal information, follow a character crossing frame, or reassign attention without changing camera position.

- Feeling: Journalistic, observational, sometimes comedic timing (reveal punches).

- Tips: Use pan/tilt with motivated cues (a glance, a sound). Slow down for grandeur, speed up for surprise. On tripods, counterbalance and fluid head drag matter more than brand.

Dolly/Track

- What it is: Physically moving the camera forward/backward or laterally on a track or wheeled platform.

- When to use: Character introspection (push-ins), spatial reveals (pull-backs), dynamic parallel movement.

- Feeling: Cinematic, deliberate. Smooth dolly is read as confident.

- Tip: Place foreground elements to enhance parallax; it makes movement feel richer without moving faster.

Push-In / Pull-Out

- What it is: Moving toward or away from your subject, typically along the Z-axis.

- Feeling: Push-in concentrates attention; pull-out diffuses it.

- Example: David Fincher’s subtle push-ins at key revelations (e.g., Zodiac) raise tension without dialogue.

Arc / 360 Hero Shot

- What it is: Orbiting around a subject.

- Feeling: Romantic, energetic, or disorienting depending on speed and radius. Michael Bay’s 360 hero shot imbues momentum and swagger.

- Tip: Keep the background interesting so the orbit feels purposeful; clean a circular path for safety.

Crane/Jib

- What it is: Vertical or sweeping move using a levered arm.

- Feeling: Elevated perspective, grandeur, transitions from details to context.

- Example: La La Land’s freeway opener uses crane and handheld blending to feel joyous and expansive.

- Tip: Previsualize start/end frames; crane moves are time‑consuming and benefit from precise marks.

Steadicam and Gimbals

- What it is: Stabilized systems that allow fluid movement by an operator on foot.

- Feeling: Human yet smooth. Steadicam has an organic float; gimbals can feel crisp and robotic unless tuned.

- Example: Goodfellas’ Copacabana oner (Steadicam) creates intimacy and status.

- Tips: For Steadicam, dial in drop time (~2–3 seconds) for balanced returns. For gimbals, choose modes wisely (pan follow vs lock) and practice footwork (“ninja walk”).

Handheld

- What it is: The camera is held by hand or shoulder.

- Feeling: Raw, immediate, anxious. The Revenant leverages handheld to feel elemental.

- Tip: It’s not an excuse for chaos; control your wobble frequency and amplitude. Consider an Easyrig for fatigue and a small top handle for micro-stability.

Slider

- What it is: Short-throw linear moves on a small rail.

- Feeling: Subtle polish; often used for inserts or interviews.

- Tip: Put objects in foreground to maximize the minimal travel.

Drone/Aerial

- What it is: A camera on a multi-rotor or fixed-wing platform.

- Feeling: Freedom, scale, surveillance, dread (depending on altitude and angle).

- Example: Establishing the setting in The Social Network’s rowing scenes pairs aerial glide with rhythmic music to set tone.

- Tip: Fly legal (more later), choose ND filters for proper shutter, and plan wind contingencies.

Vehicle and Rig Moves

- What it is: Camera mounted on or tracking with vehicles: car mounts, process trailers, pursuit arms (e.g., U‑Crane), or e‑bikes.

- Feeling: Kinetic immersion. Children of Men’s car ambush uses a custom rig for 360 interior moves.

- Tip: Secure rigging with redundancies; confirm load ratings. Coordinate with stunts and traffic control.

Motion Control and Repeatable Moves

- What it is: Robotic systems that repeat exact paths, ideal for VFX composites.

- Feeling: Supernatural precision.

- Example: Commercial tabletop and VFX duplication shots; repeat takes to composite multiple performances.

- Tip: Budget time. Even simple moves require programming and safety checks.

Lenses, Distance, and Parallax: Why the Same Move Feels Different

A push-in on a 24mm lens feels nothing like a push-in on a 100mm. Three variables change the emotional read:

- Field of View and Compression

- Wide lenses (14–35mm): Expand space, exaggerate foreground movement, enhance parallax. Pushing in on a 24mm makes backgrounds drift quickly, amplifying urgency.

- Telephoto lenses (85–200mm+): Compress space, reduce parallax, keep background scale more constant. A push-in on a 135mm feels like psychological narrowing rather than spatial travel.

- Camera-to-Subject Distance

- Moving a meter is not the same as changing framing by zooming. Physical movement changes the relative size of foreground/background (parallax), while zooms alter framing without changing spatial relationships. Audiences feel the difference subconsciously.

- Perspective Control and Eyelines

- Wide lenses up close can distort faces; telephotos flatten features. A close pass with a 21mm can feel intimate or invasive; the same with a 100mm feels voyeuristic or compressed.

Practical guidance:

- If you need movement to “read,” go wider and introduce foreground elements—a chair back, a door frame, a passerby. This gives the eye reference points.

- If you want a subtle psychological move, go longer and move less; small dolly progresses will still alter perspective enough to feel a shift.

- Respect the subject’s comfort zone. A lens at 50 cm from an actor’s face is not the same emotional experience as standing 3 meters away on a 100mm.

Blocking, Geography, and the Z-Axis

Movement doesn’t live in a vacuum; it’s born from blocking. Good blocking turns movement into storytelling logic.

- Start/End Frames: Before you move, ask: what is my starting emotion and what is my landing emotion? Frame for the arrival as carefully as the departure.

- Z-Axis Play: Moving characters toward/away from camera changes power dynamics. A character stepping into the lens feels confronting; retreating feels diminished.

- Eyeline and 180-Degree Rule: If you cross the line while moving, do it intentionally—ideally on a motivated action or within an environment change. A circular move that crosses the axis can signal a turn in perspective.

- Geography Breadcrumbs: Use landmarks—lamps, doorways, signage—to give viewers spatial anchors as you move.

- Foreground Extras: Plant extras or props to create dynamic foregrounds. A static walk-and-talk feels alive if a passerby briefly occludes the frame, introducing parallax and realism.

On set, overhead diagrams are your friend. Sketch the room, mark talent paths, camera path, and key sightlines. A 10-minute whiteboard can save an hour of flailing.

Planning the Move: Previs, Storyboards, and On-Set Workflow

Moves that look effortless were rarely improvised. A solid plan integrates creative, technical, and safety considerations.

- Storyboards and Shot Lists: Define intent and beats per move. Are you revealing a clue on beat three? Note it. Mark lens choices.

- Overheads and Tech Scouts: During a tech scout, walk the path. Measure distances. Identify trip hazards, light stands, and cable runs. Pre‑rig where possible.

- Previsualization (Previs): For complex choreography—stairwells, multi-room oners—use phone video, previs apps, or 3D animatics. Even crude previs will expose timing issues.

- Rehearsals: Separate actor rehearsal from camera rehearsal, then combine. Run without sound or with “speed” but no roll to preserve energy.

- Marks and Timing: Tape marks on floors. Use metronome counts or the assistant director’s cues for synchronization. “3, 2, move” is a lifesaver.

- Contingency Frames: Plan bail-out frames. If a background extra misses a cue, can you land on a close-up that still works?

Workflow checklist:

- Check lens breathing and whether zooms are parfocal.

- Confirm aperture ramping on variable aperture zooms; avoid exposure jumps mid-move.

- Power budget for gimbals, monitors, wireless follow focus.

- Slate “Move Rehearsal” takes to document improvements.

Case Studies: Iconic Moves and Why They Work

-

Goodfellas (Copacabana oner): A Steadicam follows Henry and Karen through the back corridors into the club. Why it works: The continuous move establishes status (backdoor access), seduction (sea of attention), and point of view (we’re in Henry’s glide through life). Technically, it’s a blend of tight blocking, on-the-fly lighting handoffs, and practiced operators.

-

1917 (seamless long-take approach): A composed series of oners stitched invisibly. Movement maintains real-time immediacy. Why it works: The camera is empathetic—staying at soldier height most of the time, rising only when necessary. It also showcases careful lensing (wide angles for parallax and proximity) and hidden cuts on wipes, dark surfaces, and motion vectors.

-

Children of Men (car ambush): A custom rig allowed the camera to move 360 degrees inside a car. The move funnels panic: from driver to passengers to windows to threats. Why it works: Technological innovation serving story—movement distributes attention with increasing dread.

-

The Revenant (bear attack and traversal): Handheld, bravura long moves escalate urgency. Why it works: Earthy instability matches survival chaos; movement interacts with natural light to feel unvarnished.

-

Fincher’s slow pushes: Across films like Zodiac and The Social Network, slow, nearly imperceptible push-ins tighten focus without showiness. Why it works: Precision in speed and composition—moves often finish on a key line or reaction, subtly steering attention.

-

Spielberg “oners”: Spielberg often favors oners with internal blocking (characters move within a developing frame). Why it works: Blocking makes the shot feel alive, movement adds grace without calling attention to itself.

-

Park Chan-wook’s sliding frames: Controlled lateral moves that reveal layers. Why it works: Movement as misdirection and revelation—what is hidden slides into view with timing.

Lessons from these examples: The best moves have a narrative verb: seduce, suffocate, escalate, reveal, dignify, diminish.

Movement and Editing: Rhythm, Transitions, and Invisible Stitches

Movement dictates editorial rhythm, not just within shots but between them.

- Coverage vs Oners: A well-executed move can replace three cuts, but it also demands precision in performance and timing. If you commit to a oner, plan safety cut points (door frames, whip pans, foreground wipes) you can use to bail.

- Movement as Transition: Whip pans can hide cuts. Match the direction and speed; cut at the blur peak. Crash zooms, foreground wipes, and match-move tilts are similar tools.

- Invisible Stitches: Hide joins in darkness, on a body passing close, or in a quick occlusion. Keep parallax and exposures similar on both sides of the stitch.

- Editorial Rhythm: Movement can compress or dilate time. A dolly-in that starts before a line often pushes the emotional beat forward; a dolly-out that continues after a line lets it resonate.

- Sound Bridges: Let sound lead the move or carry the cut. An L‑cut that introduces the next scene’s audio at the tail of a move readies the audience’s attention.

Actionable tip: When designing a move, mark potential edit points along the path. If take 4 nails the first half but stumbles later, you’ll know where to hide a splice with take 6.

Sound, Lighting, and Movement: The Hidden Variables

Movement complicates everything else.

Sound:

- Boom vs Lav: If the camera travels far, lavs offer consistency; booms can shadow you if well-coordinated. Map the boom’s path while planning the move, including ceilings and reflective surfaces.

- Footfalls and Gear Noise: Gimbal operator steps, dolly wheel squeaks, and cable drags are audible. Lay dance floor or mats for soft steps. Use rubber wheels on carts.

- Doppler and Perspective: As you move, sound perspective should change. Decide whether to keep sound “objective” or track with the camera’s proximity.

Lighting:

- Light Handoffs: In oners, movers carry flags and bounce cards. Practicals (lamps) boost flexibility, letting performers move through consistent levels.

- Exposure Ramps: Moving from interior to exterior? Use variable NDs or iris pulls. Avoid variable ND flicker by using high-quality filters and testing at your shutter speed.

- Color Temperature Shifts: Crossing from tungsten to daylight? Hide gels or use bi‑color fixtures that change mid‑move; set the camera’s white balance strategy.

Camera Settings:

- Shutter and Motion Blur: Rapid pans/whips need appropriate shutter angles. Too-fast shutter makes judder; too-slow creates smear. Test what feels right for the project’s texture.

- Rolling Shutter: CMOS readout can skew verticals on fast moves. Avoid extreme whip pans on cameras with slow readout, or plan for cuts.

Tools, Tech, and Budgets: From Indie Hacks to High-End Rigs

You don’t need a crane truck to move meaningfully. Choose the tool that fits your budget and intent.

Indie-friendly options:

- DIY Dolly: A sturdy wheelchair, furniture sliders on dance floor, or PVC pipe track with a skate dolly. Test weight and safety.

- Sliders: 60–120 cm sliders deliver invaluable micro-moves. Mount on heavy tripods or apple boxes for stability.

- Gimbals: 3‑axis gimbals (Ronin, MoVI, Crane) offer smooth handheld. Balance carefully. Use underslung or top handle modes for low angles.

- Post Moves: Shoot 4K and deliver 1080p, then add subtle digital push-ins/pans. Keep to 5–10% to avoid resolution loss or noise amplification.

Mid/high-end:

- Steadicam: Requires trained operator. Budget for prep time and spotters.

- Jibs and Mini Cranes: Useful for repeatable vertical sweeps. Combine with track for compound moves.

- Remote Heads and Stabilized Systems: Allows precise moves on dollies/cranes and vehicle rigs.

- Motion Control: Repeatable precision for VFX and tabletop. Great for product work, narrative magic, and time-lapse.

Accessories that matter:

- Wireless video and focus: Prevent tethers from fouling movement. Assign a 1st AC to pull focus remotely.

- Power distribution: Keep gimbal plus camera powered; fewer battery swaps means fewer interruptions.

- Communication: Headsets for operator, 1st AC, and AD. Movement relies on clear cues.

Safety, Law, and Ethics When Things Move

Movement increases risk; treat it with respect.

- Rigging Redundancy: Use two independent points for any overhead or vehicle mount. Safety cables are not optional.

- Spotters: Assign spotters to the operator’s blind side, especially on stairs/terrain.

- Stunt and Traffic Coordination: If moving with vehicles or fight choreography, integrate with stunt coordinator early. Rehearse at half speed.

- Permits and Insurance: Moving camera rigs in public spaces often require permits. Insurance should list rigging and aerial operations if applicable.

- Drones: Follow local regulations—certifications, altitude and distance limits, visual line of sight, no-fly zones. Keep safe distances from people and property; have a pilot and a visual observer.

- Crowd Control: Moving cameras can startle bystanders; use lock-ups and clear signage.

Ethics:

- Respect privacy and safety. Don’t push risky moves for ego. If a move endangers cast/crew or bystanders, redesign it.

Virtual Production and Digital Movement

The digital frontier expands what “movement” can mean.

- LED Volumes: In-camera VFX on LED walls allow parallax when combined with camera tracking. A short real dolly can create a vast simulated movement in the background. Movement must be synced to virtual camera for correct parallax.

- Simulcam and Previs: Overlay CG elements on live feeds for precise on-set framing. You can choreograph a crane move that seamlessly matches a CG extension.

- Virtual Dolly/Camera in Post: Within 6K/8K plates, delicate re‑frames, push-ins, and tilts are possible. Keep to modest ranges to avoid resolution and noise issues.

- Motion Control for Plates: Repeat paths to capture clean/background passes. This lets you composite moving elements convincingly.

Pro tip: Even in virtual production, physical movement sells reality. Combine small real moves with larger virtual background movement for depth.

Practical How-Tos: Setting Up 5 Essential Moves

- The Subtle Dramatic Push-In

- Intent: Intensify focus on a key line or realization.

- Setup: 35–50mm lens, dolly on dance floor, foreground element near frame edge.

- Steps:

- Mark start/end positions (e.g., 1.2 m travel).

- Set a slow, constant speed; use an app-based metronome to pace grips.

- Pre-roll; initiate move two beats before the key line to arrive on the reaction.

- Pull focus with marks every 30 cm; use focus peaking on a high‑nit monitor.

- Pitfalls: Over-speeding. If the move is noticed, it’s probably too fast.

- The Lateral Reveal

- Intent: Introduce information from behind an occluder.

- Setup: Slider with 70–100 cm travel; place a doorway frame foreground.

- Steps:

- Compose initial negative space; hide subject.

- Move at steady pace; reveal at the line or sound cue.

- Add a background extra crossing late to sell depth.

- Pitfalls: Dead backgrounds. Dress set behind the reveal.

- Whip Pan Transition

- Intent: Hide a cut or jump in time/place.

- Setup: Fluid head with set pan drag.

- Steps:

- From shot A, whip right; cut at peak blur to shot B whipping right into new frame.

- Match pan speed and direction. Consider adding a motion blur/optical flow assist in post.

- Pitfalls: Mismatched exposure or horizon. Shoot both sides under similar conditions.

- Gimbal Walk-and-Talk

- Intent: Fluid following of two or more actors.

- Setup: 24–35mm on a balanced 3‑axis gimbal; wireless focus; two rehearsals minimum.

- Steps:

- Balance gimbal perfectly; auto-tune motor strength.

- Choose mode: Pan follow, tilt/roll locked; set deadband to avoid bobble.

- Operator does “ninja walk”; 1st AC pulls focus with marks.

- Block boom operator path to avoid dipping into frame.

- Pitfalls: Horizon drift. Calibrate IMU; engage roll trim.

- Drone Establishing Glide

- Intent: Set scale and context.

- Setup: Prosumer quadcopter with ND; 24/48/60 fps depending on desired motion clarity.

- Steps:

- Preflight checklist; confirm home point, satellites, compass.

- Plan a low, forward parallax pass with foreground trees/buildings.

- Keep shutter around 1/100–1/120 for natural motion blur.

- Fly in tripod/cinematic mode to smooth acceleration.

- Pitfalls: Wind gusts and props casting shadows at low sun angles; plan time of day.

A Director’s Movement Palette: Designing a Style

The most recognizable directors curate a movement palette aligned with their themes.

- The Minimalist: Sparse moves, often reserved for emotional peaks. Static frames create pressure; a rare push-in releases or intensifies.

- The Immersive: Frequent, flowing movement that keeps the audience inside space and time (Cuarón, Iñárritu). Emphasis on geography and continuity.

- The Operatic: Bold crane sweeps, arcs, and dynamic angles that amplify drama (think musical numbers or stylized thrillers).

- The Procedural: Precise, low-key moves that suggest intelligence and control (Fincher). Slow pushes and microslides mirror analysis.

Build your palette:

- Identify recurring story verbs (reveal, confront, isolate). Assign movement strategies to each verb.

- Define default lensing: e.g., 27–35mm for handheld proximity, 50–85mm for restrained dolly.

- Establish speed “lanes”: e.g., emotional beat push-ins at 0.2 m/s; revelations at 0.35 m/s.

- Create rules—then break them only with intention.

A 10-Move Toolkit and When to Use Each

- Slow Push-In: For dawning realization or confession.

- Retreating Pull-Out: For isolation after a setback.

- Lateral Track: For active dialogue and momentum.

- Arc: For relationship dynamics—dance, conflict, union.

- Over-the-Shoulder Drift: For investigative POV, discovery.

- Rise and Reveal (Jib): For context shifts—small to large.

- Whip Pan: For energetic transitions and comedy beats.

- Crash Zoom + Dolly: For stylized shock (use sparingly).

- Steadicam Oner: For immersion in process or space.

- Drone Push-Through: For scale and awe (avoid cliché by keeping low and using parallax).

Pair each with a story beat, not a gear demo. Ask: What does this move make the audience feel at this moment?

Troubleshooting: Common Issues and Fixes

- Wobble/Walking Bob on Gimbal: Lower your center of gravity, bend knees, roll feet, use a small counterweight, or add a 2‑axis spring arm. Increase smoothing in software if available.

- Rolling Shutter Skew: Reduce pan speed or use a camera with faster readout; add vertical lines to your composition to detect skew early.

- Focus Pull Misses: Pre-mark distances; use focus assist tools. If depth of field is razor thin, consider stopping down or using slightly wider lens.

- Exposure Flicker with Variable ND: Use high-quality VNDs; avoid crossing the polarization “X” pattern. Consider fixed NDs and iris pulls.

- Horizon Drift on Gimbal: Calibrate every day; check for magnetic interference.

- Dolly Bumps: Lay track on level terrain; shim properly. Test with a low, long lens which exaggerates bumps.

- Post Stabilization Artifacts: Warp Stabilizer or similar can bend straight lines. Reduce percentage or switch to position/scale only.

- Actor Pacing Mismatch: Use metronome beats in earwigs or give verbal cues on set (“and… now”).

- Lighting Shadows Enter Frame: Assign a shadow patrol PA; rehearse all crew paths.

A Sample Shot Plan You Can Steal

Scenario: Two characters argue in a small apartment kitchen, ending in a quiet reconciliation at the window.

Beat 1: Arrival and Tension

- Shot A: Locked-off wide master, 24mm, slight low angle, framed to include doorway foreground. Purpose: establish geography.

- Shot B: Lateral slider move (70 cm) on the counter, passing behind a coffee maker to reveal Character B entering. Purpose: motivated reveal and parallax.

Beat 2: Escalation

- Shot C: Handheld medium over-the-shoulder on Character A, 35mm. Small, reactive moves to match rising tension. Purpose: human unease.

- Shot D: Opposing handheld medium on Character B, mirroring C. Purpose: visual parity.

- Shot E: Push-in on A during a critical accusation, dolly 1 m at 0.25 m/s, 50mm. Purpose: focus emotional weight.

Beat 3: Breaking Point

- Shot F: Arc 120 degrees around the island as both talk over each other, gimbal 28mm, speed ramps down near the end. Purpose: chaos merging into clarity.

Beat 4: Reconciliation

- Shot G: Dolly back 1.5 m as both move to the window, adding distance from the argument space, 35mm. Purpose: de-escalation.

- Shot H: Jib rise from waist-level two-shot up to head-and-shoulders at the window, revealing the city lights. Purpose: new perspective and release.

- Shot I: Final slow push-in from behind them, 85mm, 0.15 m/s, landing on their hands touching on the sill. Purpose: intimacy and closure.

Notes:

- Sound: Lav both; boom from the hallway on a 416, coordinate passes.

- Lighting: Practicals under cabinets; add a soft top-light through diffusion. Keep color temp consistent—3200K base with a 1/8 CTB kiss from window to suggest moonlight.

- Safety: Cable mats in the galley. Spotter for gimbal backing near the window.

This plan alternates energy: stable → reactive → fluid → elevating. Each movement is tied to a beat, not to gear novelty.

The art of camera movement is rarely about how many moves you can pack into a scene. It’s about choosing the one that serves the moment best and executing it with craft. When movement aligns with story verbs, when lenses and blocking are selected with intent, and when practical constraints are embraced as creative challenges, the camera stops being a device and becomes a voice. Train your eye, rehearse your steps, and let each move earn its place—your audience will feel the difference even if they can’t name it.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts