What Can Gunshot Residue Actually Prove in Criminal Investigations

10 min read Explore what gunshot residue can actually prove in criminal probes, demystifying its evidentiary power and limitations. (0 Reviews)

What Can Gunshot Residue Actually Prove in Criminal Investigations?

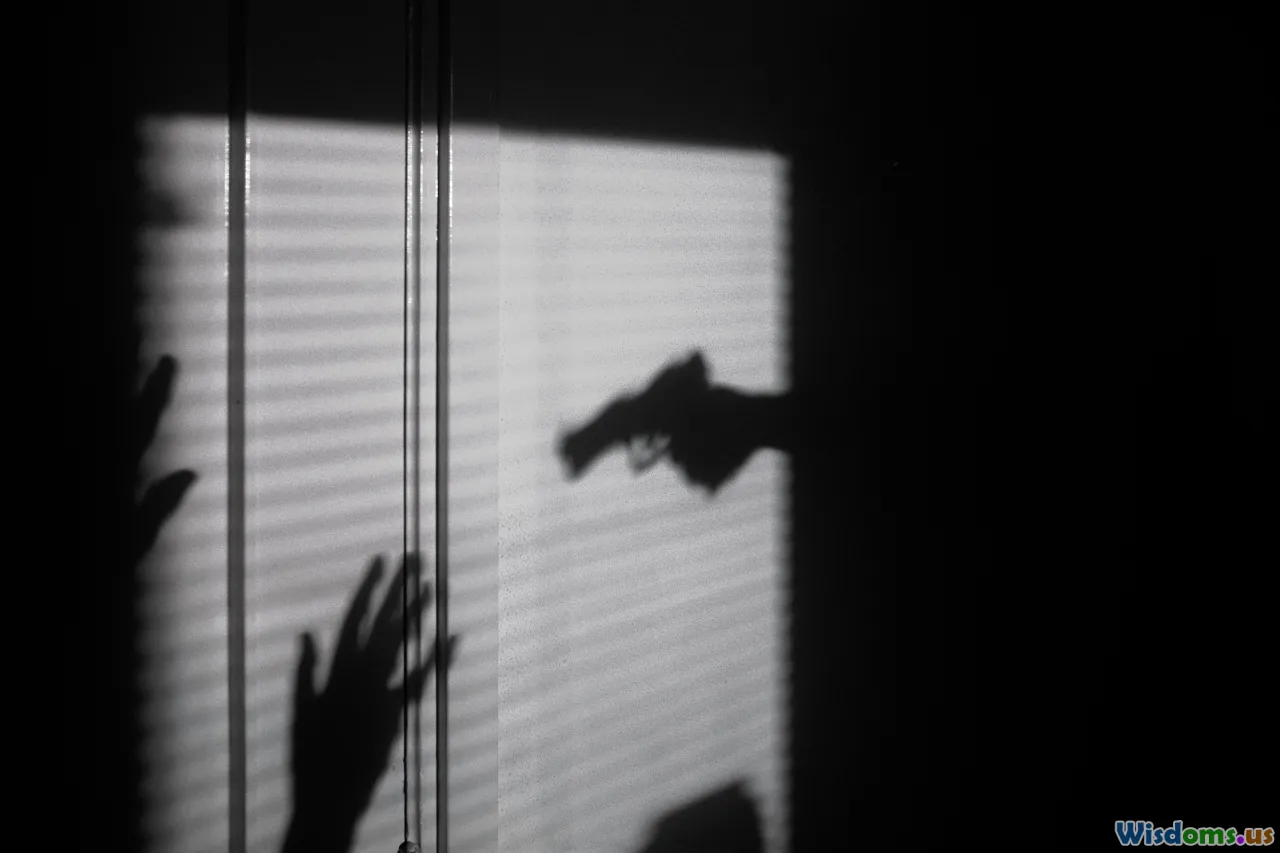

When a gun is fired, tiny particles known collectively as gunshot residue (GSR) scatter into the environment—clinging to the shooter’s hands, clothing, or nearby surfaces. On the surface, detecting GSR on a suspect might seem like an open-and-shut clue: “You fired a gun.” But like many pieces of forensic evidence, its presence and meaning are more nuanced. What exactly can gunshot residue prove in the context of criminal investigations? How reliable is it, and what are the pitfalls? This article offers an in-depth exploration of the science, practical use, and courtroom implications of gunshot residue, aiming to clarify its true evidentiary value.

Understanding Gunshot Residue: What Is It?

Gunshot residue is a complex mixture of microscopic particles composed primarily of elements like lead, barium, and antimony—byproducts of primer ignition when a firearm discharges. These particles are expelled from the gun’s barrel and can settle on the hands or clothing of the person firing the weapon, but also on nearby objects and people.

Forensic experts collect samples from suspected shooters’ hands, clothing, or objects using adhesive stubs or wipes, then analyze them using techniques such as scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX). SEM-EDX identifies the particle morphology and elemental composition unique to GSR.

What Gunshot Residue Can Positively Indicate

1. Proximity to a Discharged Firearm

The most direct inference from GSR presence is that an individual was near a fired gun. According to research and forensic protocols, a detectable quantity of characteristic GSR particles strongly suggests that the person was within a few feet of a discharged firearm shortly before sample collection.

For instance, a 2018 study in the Journal of Forensic Sciences demonstrated that GSR levels drop significantly beyond three feet from the muzzle, making distant contamination unlikely. Therefore, presence on a suspect’s hands or clothing can locate them near gunfire.

2. Possible Shooter Identification

Finding GSR on a person's hands may indicate that they fired a gun—or at least handled one immediately after firing. However, while GSR can confirm the individual was exposed to gunfire or residue-containing surfaces, it cannot alone confirm who actually pulled the trigger.

In the 1995 Mario R. Cain case in Texas, GSR was found on a suspect’s hands, but corroborating testimony and alibis were essential to proving whether the defendant had fired the weapon or was merely near the scene.

3. Gun Handling Evidence

GSR can also indicate recent gun handling or contact with surfaces contaminated by discharge. For example, a suspect might not have fired, but touching a recently fired gun or close proximity to a shooter could deposit residues.

Limitations and Challenges of Gunshot Residue Evidence

1. Temporal Decay of Residue

Gunshot residue doesn't remain indefinitely. Natural activities like washing hands, sweating, or movement help dislodge GSR particles. Time elapsed between the shooting and sample collection greatly influences detection.

The UK’s Forensic Science Service has observed that upwards of 50% of GSR particles can be lost within 4-6 hours, creating a narrow window for reliable sampling. Consequently, negative GSR results cannot definitively exclude firing involvement.

2. Possible Contamination and Transfer

Unintentional transfer of GSR is a recognized problem. Studies have documented scenarios where innocent individuals acquire GSR passively, e.g., by being near shooters, shaking hands, touching clothing/objects with residue, or even riding in vehicles shared with shooters.

For example, in a 2004 case summarized by the FBI’s Crime Laboratory Bulletin, GSR was found on a victim’s clothing though they had no involvement with the firearm, likely due to secondary transfer from the environment.

3. Alternative Sources of Similar Particles

While lead, barium, and antimony patterns are presumptive markers, certain industrial activities, fireworks, or occupational exposures can produce particles mimicking GSR. This overlap requires forensic experts to combine particle morphology and elemental analysis, but risk of false positives remains.

4. No Trajectory or Position Confirmation

Gunshot residue analysis alone cannot establish shooter position or bullet path. It confirms presence near discharge but not the dynamics of the event. Other evidence such as ballistic trajectories, eyewitness accounts, or video footage is crucial for reconstructing crime scenes accurately.

How Forensic Experts and Investigators Use GSR Evidence

Given both its value and limits, gunshot residue evidence is used carefully in conjunction with broader investigative efforts:

- Supporting Evidence: Detecting GSR strengthens other circumstantial evidence, such as eyewitness reports and ballistic matches.

- Corroboration or Exclusion: It helps corroborate suspect involvement but is rarely conclusive alone.

- Time-sensitivity: Investigators prioritize rapid GSR evidence collection post-incident to enhance value.

In modern forensic labs, GSR examination is a routine part of firearm-related cases. The U.S. National Institute of Justice highlights that positive GSR findings can lead to deeper investigation into suspect actions, but failures to detect GSR do not conclusively prove innocence.

Landmark Examples Highlighting GSR’s Strengths and Weaknesses

Case Study: The O.J. Simpson Trial (1995)

Although primarily remembered for DNA evidence, GSR played a peripheral role. Analysts detected inconsistent GSR patterns on Simpson’s clothing, raising doubts about contamination and timing. The defense argued that environmental transfer and forensic mishandling could have compromised results — spotlighting GSR’s complexities.

Case Study: The Trayvon Martin Shooting (2012)

In investigations into George Zimmerman firing a weapon, GSR collection from Zimmerman’s hands was pivotal. Despite criticisms, the residue evidence supported the assertion that Zimmerman fired his gun during the confrontation, underscoring how GSR can aid when coupled with other evidence.

Future Trends and Improvements in GSR Analysis

Advances focus on increased sensitivity, rapid on-scene testing, and differentiating primer types to trace ammunition brands. Research into organic components (powder residues) and forensic chemical signatures aims to improve discrimination from contaminants.

Emerging portable GSR analyzers offer law enforcement faster preliminaries without lab delays, though standardization and operator training remain essential components for reliability.

Conclusion: Gunshot Residue - A Powerful Clue, Not a Definitive Answer

Gunshot residue is an important forensic tool that can demonstrate presence near a discharged firearm and suggest possible involvement in shooting events. However, its evidentiary power is bound by technological limits, environmental factors, and interpretive challenges.

Crucially, GSR detection should be integrated thoughtfully among physical, testimonial, and circumstantial evidence—not viewed in isolation. Understanding the science behind GSR, its detection windows, and contamination risks enables more accurate criminal investigation and fair justice outcomes.

In the evolving landscape of forensic science, gunshot residue remains both a beacon and a caution—illuminating critical clues but demanding careful scrutiny to separate the fire from the smoke.

References:

- Cooper, G., et al. (2018). "Evaluating the Validity of Distance Estimation Using Gunshot Residue Distribution," Journal of Forensic Sciences.

- National Institute of Justice. (2014). "Guide to Gunshot Residue Analysis."

- Scientific Working Group on Gunshot Residue Executive Summary. (2020). "State of the Art Gunshot Residue Detection and Interpretation."

- FBI Crime Laboratory Bulletin (2004). "Challenges and Pitfalls in Gunshot Residue Analysis."

By differentiating the evidentiary strengths and weaknesses of gunshot residue, investigators and legal professionals can wield this forensic tool effectively while avoiding over-interpretation.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Forensic Science

Popular Posts